Articles Menu

Feb. 15, 2024

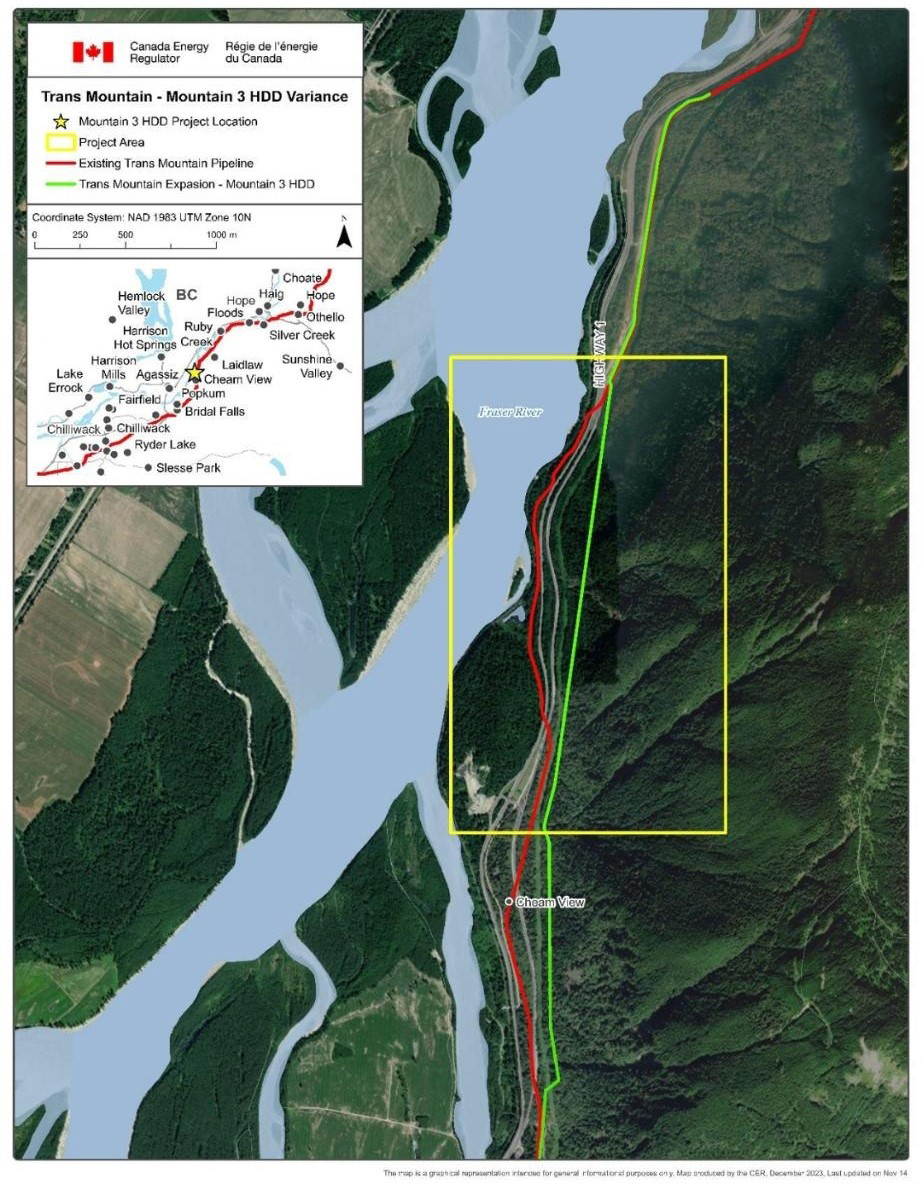

Trans Mountain’s pipeline expansion project, which began in 2013 with the aim of sharply increasing the pipeline’s capacity to bring bitumen from Edmonton to Burnaby, is facing its last big obstacle: a 2.3-kilometre wall of volcanic rock next to the Fraser River between Hope and Chilliwack that the section’s director, Jim Huber, has described as “some of the most challenging terrain in North America for pipelines.”

This 2.3-kilometre stretch is also the only place along the 980-kilometre route where Trans Mountain violated its own quality management plan when it purchased a new set of pipe materials to go through it.

That’s because of a last-minute change to scrap the original pipe for a smaller, narrower one in the hopes of getting it through the so-far impenetrable passage. None of the new pipe materials come from the company’s approved list of suppliers.

In fact, the pipe fittings come from a company called Ezeflow, whose pipe elbow ruptured in a 2013 gas leak near Fort McMurray and was deemed to be substandard, leading to an advisory from the Canada Energy Regulator (then known as the National Energy Board) to crack down on substandard pipe materials.

While the Canada Energy Regulator initially rejected Trans Mountain’s first application for the updated plan, it changed course a month later in response to a followup request, allowing the company to use the new pipes in the section known as Mountain 3.

“It’s a weird situation,” Eugene Kung, a staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law, told The Tyee. “It does not instil a lot of confidence, I’ll say that.”

The section runs alongside critical habitat for salmon and sturgeon, including a network of river islands that create nurseries for baby fish during spring snowmelt.

“This would be a horrendous place for a spill,” Romilly Cavanaugh, a former engineer on the Trans Mountain pipeline, told The Tyee. “There won’t be anything they can do to prevent hundreds of kilometres of river being damaged.”

Even with the new, smaller pipes, Trans Mountain’s problems have persisted. Last week the company announced it was having “technical issues” getting the pipe into so-far impenetrable rock, citing an undefined “obstruction” and delaying its in-service date to the second quarter of 2024.

The decade-long project’s costs have ballooned from an expected $5.4 billion in 2013 to $35 billion.

In a press release issued about the delay, the company said it would not provide interviews and said it was “fully focused” on the completion of the pipeline.

‘There is a significant risk of losing the entire hole’

Trans Mountain knew the Mountain 3 section would be difficult. The company is using a technique called horizontal directional drilling to blast a tunnel in the rock using high-power tools and drilling fluids. Once the hole is cleared, the new pipes are pulled through.

This section pushes the limits of the technology. According to a feasibility study initially developed for another horizontal drilling section of the pipeline, Mountain 3’s length, combined with the project’s original pipe diameter, verges between a “zone of limited industry application” and a category that “exceeds the current capabilities of industry,” which is “considered risky even with an experienced contractor and favourable ground conditions.”

With the new, smaller pipe, the section is in the “zone of limited industry application.” It is “considered feasible” under favourable ground conditions.

But conditions in the Mountain 3 section have not been ideal.

First, the rock is so hard that Trans Mountain regularly breaks tools while drilling. “We had to go in after and fish out the tools,” said Corey Goulet, chief project execution officer for the Trans Mountain expansion project, during an oral hearing in January.

Second, “pressurized aquifers” run through the rock and into the pipeline’s path.

Trans Mountain said that the water from these aquifers dilutes its drilling fluids, making the drilling process slow and potentially impossible. The company tried to plug the aquifers with grout, but as water levels grew, they abandoned the approach.

“The larger diameter we go, the more risk we have of that grout failing,” Goulet told the oral hearing. “There is a significant risk of losing the entire hole.”

So Trans Mountain pulled a fast pivot. “Due to the short delivery window required,” the company wrote in its first application to the energy regulator, “Trans Mountain has decided to procure stock currently available from the three manufacturers rather than placing an order for a mill run.”

The company bought a new set of 30-inch pipes and fittings for the Mountain 3 section to replace the 36-inch pipe, which runs for the remainder of the line from Edmonton to Burnaby.

But that fast purchase of surplus stock was not compliant with Trans Mountain’s quality management plan — the ninth condition placed on the pipeline cited when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau approved the project in 2019. That plan requires Trans Mountain to source materials from a set list of approved manufacturers vetted by the energy regulator. It also required pipeline materials to be made to order, allowing Trans Mountain to do ongoing inspections during the manufacturing process with oversight from the regulator.

Trans Mountain’s decision to “procure stock currently available” saw it instead purchasing surplus pipes manufactured six to eight years ago from unapproved and unvetted vendors.

“The offered pipe is second-hand pipe,” wrote Trans Mountain senior procurement specialist Naomi Goto in an email co-ordinating a purchase from one of the unvetted pipeline companies, adding that “the pipe is from a cancelled project in the USA.”

Those already manufactured pipes come with added risks, Cavanaugh said.

Trans Mountain’s quality management plan, Cavanaugh said, is “very detailed. It’s a step-by-step thing all along the way, making sure that nothing is happening to make the pipe weaker or unsuitable.”

“That’s all been scrapped,” Cavanaugh said.

In the pipeline industry, companies will typically form long-term relationships with their vendors, said Frank Cheng, a professor at the University of Calgary’s Schulich School of Engineering and an expert in pipeline corrosion.

“The industry tells me they feel comfortable,” he said. “They know the products and their properties.”

Without that long-term relationship, Cheng sees cause for concern. “It’s not good,” he said. “It’s not a usual situation.”

Trans Mountain’s problems with horizontal drilling extend beyond the Mountain 3 site, including a last-minute change to its route design tunnelling under the Fraser River, which was approved by the Canada Energy Regulator in 2022.

In September, the Canada Energy Regulator approved another variance request, allowing Trans Mountain to trench through a sacred cultural site belonging to the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc Nation after the company’s attempts to drill through harder-than-expected rock had cost additional time and $32 million. Work in the area known as Pípsell, in the Jacko Lake area southwest of Kamloops, is expected to wrap up later this month, a spokesperson said in an email to The Tyee.

The regulator’s first denial

A month after Trans Mountain’s purchase of the second-hand pipe, the company applied to get the energy regulator’s approval to use it. At the time, Trans Mountain projected a two-month construction delay if its new plan to use smaller pipes was rejected. Its initial application did not mention that the purchase from unvetted vendors violated the company’s own quality management plan.

“Trans Mountain has determined that there is no material change to the pipeline risk assessment,” the company asserted instead.

The energy regulator disagreed. “The Trans Mountain Expansion Project is a regulated project with a high [Canada Energy Regulator] oversight and public scrutiny,” it wrote in its reasons for rejecting the application. “Quality of materials cannot be compromised due to Trans Mountain’s urgency” to finish the project, it said.

A week after the regulator’s refusal, Trans Mountain returned again with a new but tweaked application.

“We really had no choice,” said Trans Mountain’s legal counsel, Sander Duncanson, at the application’s oral hearing in January. “If Trans Mountain cannot proceed with the requested variance, the consequences could be truly catastrophic from the perspective of Trans Mountain and the project.”

The company said it would build additional infrastructure to allow for more internal testing of the pipe before and after construction. Its plan to install the new, smaller pipes remained. And this time, the stakes had grown. “The water issue was always known to be an issue,” said Duncanson. “It was not understood to be a significant issue until recently.”

Now, the company said, it risked losing its existing borehole altogether due to the amount of water coming in. The company projected a two-year delay if its plan to use smaller pipe didn’t go ahead, which Duncanson said would “have significant impacts to Trans Mountain and third parties who are relying on completion of this project.”

Those third parties made their concerns known: the province of Alberta and Trans Mountain’s future oil shippers submitted letters calling for the CER to approve the plan.

“Canadian Natural has a direct and substantial interest in the timely completion of the Trans Mountain Expansion Project,” wrote the oil producer and future customer of Trans Mountain’s new line, adding that the regulator’s approval of the variance “should be provided without delay.”

A few weeks later, the Canada Energy Regulator approved the revised variance application, requiring that Trans Mountain test “a sample” of its new pipes for material quality.

In an emailed statement, the regulator told The Tyee it did not specify the number of samples that Trans Mountain must conduct. It added that its conditions “focus on Trans Mountain validating the stated material properties of pipes from each manufacturer,” and that Trans Mountain’s commitments to additional testing and their new sampling requirement “will result in an equivalent level of material quality” as Trans Mountain’s original quality management plan.

Cavanaugh remains concerned. “One sample would be the absolute bare minimum,” she said. “That wouldn’t be considered standard quality assurance. It’s super watered down.”

Inspection gaps

Trans Mountain says its new, smaller pipes were systematically inspected “upon receipt.” Then they carried out “multiple inspections” as they were recoated with a layer of fusion bond epoxy and a hard top coat.

“The process that was followed was at the highest level of inspection standards for the industry,” said Duncanson during the January hearing.

But that process might have let some issues fall through the cracks.

Trans Mountain’s first inspection report upon receipt of the pipes accepted all the pipes provided, adding that “no physical damage, excessive corrosion or ovalities were noted.”

But in subsequent inspections, others noted physical damage.

One inspector noticed a “large defect” in a pipe about 23 centimetres long, which was subsequently cut off from the pipe.

In another inspection during the coating process, an investigator flagged “slivers” carved into a pipeline that were “deeper than they appeared.”

And those subsequent inspections had gaps. Multiple reports indicate that “due to safety concerns and limitations while loading,” the inspector was unable to check the full body of a length of pipe as it was being loaded into the trucks.

And during the recoating process inspectors noted that facilities were often short-staffed. In one instance, that meant workers couldn’t fully turn the pieces of pipe to inspect them. Other times, the operations seemed to be moving too fast to check.

The energy regulator also noted that Trans Mountain had no criteria or measurement system to determine the defects considered acceptable.

In a statement emailed to The Tyee, Trans Mountain said that “all pipe was either found acceptable per Trans Mountain specifications or rejected.”

When the energy regulator approved the company’s new application in January, it also flagged miscalculations around the pressure new, smaller pipes would sustain. “In light of the errors noted above,” wrote the regulator, “it is prudent for Trans Mountain to review the analysis of pipe stresses.” It asked that the company inform the regulator “of any resulting clarifications or corrections.”

In an emailed statement, the Canada Energy Regulator told The Tyee that “Trans Mountain stated that all required pipe calculations have been performed” for the section of pipe in question and that all the pressure and stress levels “have been assessed” and are within the limits deemed acceptable under the Canadian Standards Association’s standards for pipeline safety and integrity.

A perfect storm

Even with perfect pipe materials, leaks can still happen. That’s because pipeline spills’ key culprits — corrosion and cracks — can also stem from the environmental conditions they’re exposed to.

According to Cheng, terrain like that in the Mountain 3 section can be particularly damaging.

“Rocks with lots of water will be much more aggressive compared to other geographic regions,” Cheng told The Tyee, adding that water can corrode pipeline coating, and rock walls tend to shift and exert pressure on the pipeline.

Trans Mountain has acknowledged that the section has a pre-existing risk of debris flows and landslides.

In an emailed statement, Trans Mountain disagreed that the Mountain 3 section is particularly problematic. “These conditions make no difference to the effects of corrosion or the service life of the pipeline,” it said.

Cheng said pipeline engineers are developing better coating treatments that can help better withstand corrosion, and metal casing can help ward against sliding rocks. But the risk always remains. “You cannot 100 per cent control it,” he said.

In-line tests and sensors offer another line of defence. In Trans Mountain’s subsequent applications, it committed to running a suite of diagnostic tests inside the line, which can help identify issues, particularly the level of corrosion.

But once the pipeline is in the rock, companies have few options to do intensive restoration work on the external pipe without stopping the line and pulling the pipe out altogether — a process that comes at substantial expense.

“What happens long term if something goes wrong?” asked Kai Nagata, communications director for Dogwood. “There’s no way to dig it up to check and there’s no way to access it if those welds ever pop,” he said.

In an emailed statement, Trans Mountain said that “the pipeline will be maintained within the safe licensed operating limits and requirements.”

“Trans Mountain has corrosion protection programs that meet all necessary requirements,” it added. “These programs are in place for the lifespan of the pipeline.”

As the January hearing concluded, and before the regulator announced its approval, Canada Energy Regulator commissioner Trena Grimoldby asked how, after over a decade and “all of the checks and balances, all of the checks on the checks and balances, how did we get here today with you all here and yet another variance application here before us?”

“When you’re executing a project that’s 1,000 kilometres long and has all these challenging technical areas along it, there’s just this constant iterative process of let’s solve the next problem,” Duncanson said in reply.

“I’m cautiously optimistic this is the last one.”

Zoë Yunker is a Victoria-based journalist writing about environmental politics.

[Top photo: Trans Mountain’s expansion project is stuck at a section of hard rock containing pressurized aquifers running alongside the Fraser River. Photo via Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC.]