Articles Menu

May 1, 2025

Almost two decades after B.C. committed to slash greenhouse gas emissions, the provincial government reported one of the largest annual increases in decades and conceded that it won’t meet its 2025 target..

The revelations were in the fine print of its new climate change accountability report released Tuesday. It shows emissions spiking thanks to increases in sectors like gas fracking and transportation.

The province now estimates it will miss its emissions reduction target for this year and fall far short of its promised reductions by 2030.

“The purpose of the report is to be absolutely clear on these points that we are not on track to meet our near-term 2030 goals,” said Energy and Climate Solutions Minister Adrian Dix at a news conference in Victoria.

Last year’s accountability report painted a far rosier picture. The government forecast that its CleanBC plan, if implemented, would result in the province almost meeting its 2030 target.

But that projection included the impact of rules the province had not enforced and targets with no clear policies supporting them.

This year’s accountability report cut out some of that aspirational modelling, revealing a major gap in B.C.’s climate action.

The government passed legislation mandating a 16 per cent cut in emissions from 2007 levels by 2025 and 40 per cent by 2030.

But the latest report projects emissions will be only 2.6 per cent below 2007 levels by 2025 and 20 per cent lower in 2030, far short of the targets.

“We’ve got legislative targets, and we’re not even projected to be halfway there,” said Jeremy Valeriote, BC Green interim leader and MLA for West Vancouver-Sea to Sky, who described the news as “disheartening and scary for the next generation and the ones after that.”

“We really need to get down to business,” he said. “We’ve lost way too much time.”

B.C.’s emissions reporting is always a few years behind, meaning this year’s accountability report is based on emissions data from 2022.

The update shows emissions from oil and gas extraction, domestic aviation and road transport made up the biggest increases relative to 2021, while emissions from things like agriculture and waste remained mostly stable.

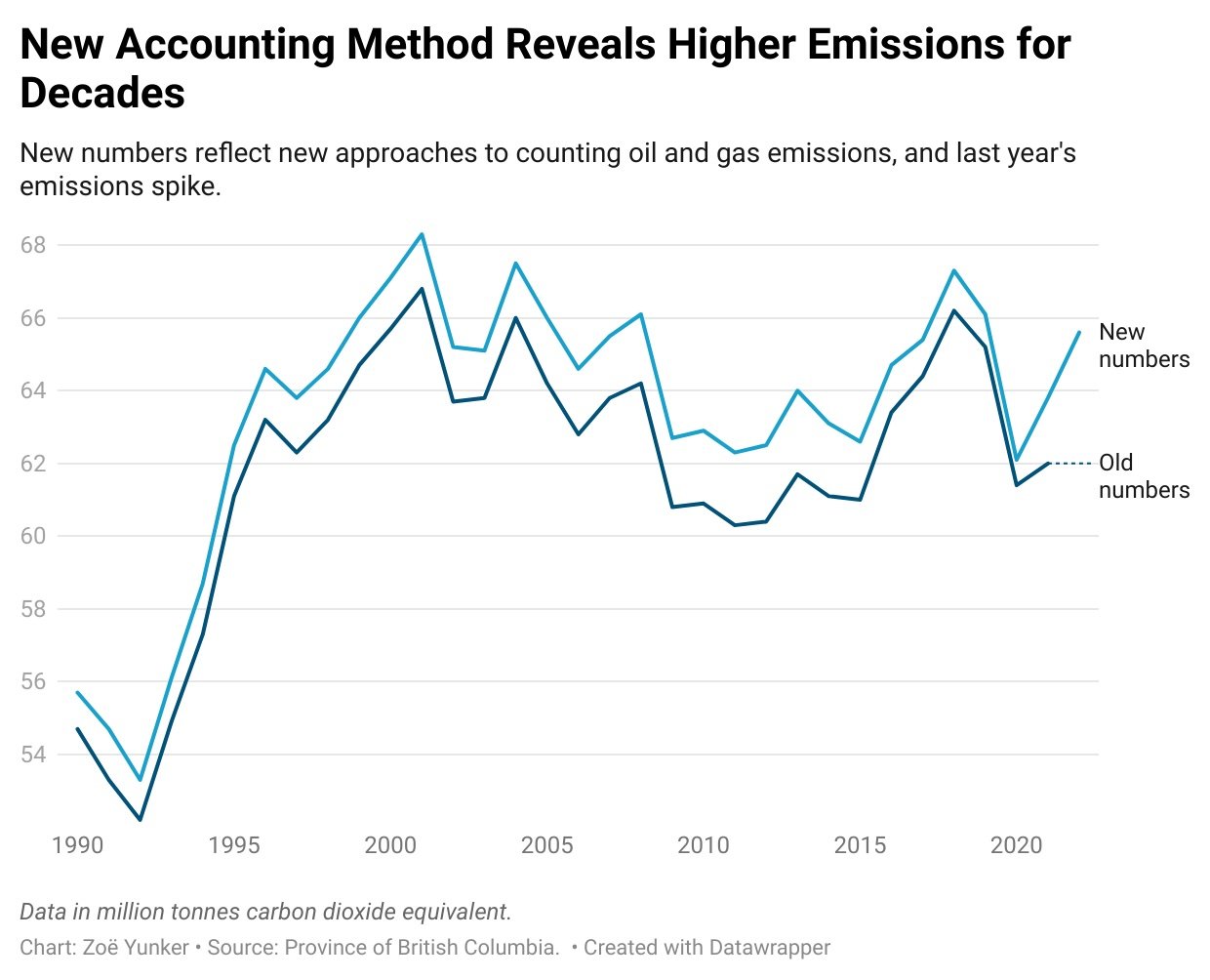

This report also reflected a major change in the way B.C. calculates leaking emissions from oil and gas extraction, meaning the province’s total emissions dating back to the 1990s were substantially higher than previously reported. The province anticipates increased gas fracking to service new liquefied natural gas projects.

Transparency questioned

B.C. is legally required to publish an annual breakdown of its emissions data and a subsequent climate change accountability report, which details its current climate policies and forecasts its planned emissions reductions based on those plans.

But those reports are often opaque, said Matt Hulse, a lawyer with Ecojustice.

“We’ve been calling on the B.C. government for the past four or five years of reporting to deliver more detail in these reports so we can understand the progress they anticipate making.”

For example, last year the province said it would “reduce distances” in light-duty vehicle travel by 25 per cent by 2030. It didn’t specify how that would happen.

It also said it would “enhance” its program to require industry to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but offered no details on what that might look like.

Despite those ambiguities, the assumptions were included in last year’s forecast, which suggested the province’s CleanBC policies could almost reach its targets.

In a transition briefing note published last year, government staff warned Dix that “the Province is no longer expected to achieve the level of emissions reductions in CleanBC.”

Several policies “have been changed from original intent in such a way that they have significantly less emission reduction than initially modelled,” it said.

Dix did not directly answer The Tyee’s questions about which CleanBC policies had changed since the province released its report last year.

“I think what that’s reflecting is we haven’t met the target we want to be at,” said Dix. “And so we have to review the programs to make sure that they’re effective and they achieve those goals.”

But this year’s accountability report offered some clues. This year’s modelling scrapped assumptions about the impact of the industrial carbon tax, which still hasn’t been implemented, and assumptions about reduced transportation distances.

“This year, the projection relies on scenarios that consider the current policy landscape,” said the report. That includes a forecast for climate policies already in place, and a second forecast that details policies that are “sufficiently advanced to be accurately assessed.”

That leaves a growing divide between its climate targets and anticipated emissions reductions.

University of British Columbia professor Kathryn Harrison is glad to see B.C.’s more honest approach. “It’s delivering bad news, but you know, better for us to know,” she said.

But Harrison said some areas remain fuzzy.

For example, this year’s report still doesn’t describe which specific policies and rules it’s relying on in its modelling. “They haven’t broken that down policy by policy,” she said.

And it also doesn’t specify which LNG projects it’s including in its emissions forecasts. In the past, B.C. modelled emissions only from projects that had received final investment decisions, excluding projects awaiting those decisions but that B.C. has approved to proceed. Harrison said it’s unclear whether B.C. has included those emissions in its modelling. “That’s another big area of uncertainty,” she said.

That could include LNG Canada’s second phase, which would produce an additional 2.3 megatonnes of emissions, roughly five per cent of the province’s total emissions.

Hulse said those new LNG emissions would put a major spanner in B.C.’s climate targets, requiring the rest of the province to ratchet down faster.

“We would have to adjust to those massive increases in emissions,” he said.

Harrison said the report does include some bright spots, including the province’s commitment to heat pumps and expanding renewable energy. “There’s good stuff happening,” she said.

“But the pace of policy design and policy implementation hasn’t happened fast enough to meet the targets.”

Getting back on track

The NDP committed to a review of the CleanBC plan this year as part of its agreement to win the BC Greens’ support for its government.

The Greens’ Valeriote said the climate report is a “wake-up call and foundation” for the review.

“If what we’ve done so far hasn’t worked, then it’s time for some new solutions,” he said. “CleanBC needs to shape up.”

Valeriote said the coming review will include opportunities for public participation.

So far the province doesn’t have any legal requirements to implement the review’s findings, but Valeriote said they would be “pushing hard” to have them implemented.

He also said the party may consider adding legal requirements if it signs renewed agreements next year.

Harrison said the sobering climate change accountability report signals the challenge of making the major emissions cuts required, adding she sympathizes with the province’s task of making tough decisions in the face of the affordability crisis and Donald Trump’s tariffs.

But Harrison said the most effective climate actions, like imposing regulations and carbon pricing systems, are politically difficult but essential.

“It’s not enough to put together a plan,” she said. “It gets harder when it comes time to actually do the stuff.”