Articles Menu

Nov. 2, 2022

Can BC afford to make major new public investments to address crises in housing, climate change, health care, child care and toxic drugs, among others?

The simple answer is yes, can we ever.

A new report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ national office shows that despite dire predictions that the pandemic would be a big blow to provincial finances across the country, most provinces today have enough funds to pay for the important programs and investments that Canadians need to survive and thrive.

A close look at the most-recent figures from BC’s Ministry of Finance confirm that big action to address social and environmental crises is well within our power in this province. In fact, the extent of BC’s fiscal and economic latitude goes beyond that discussed in the national report.

Big action to address social and environmental crises is well within our power in this province.

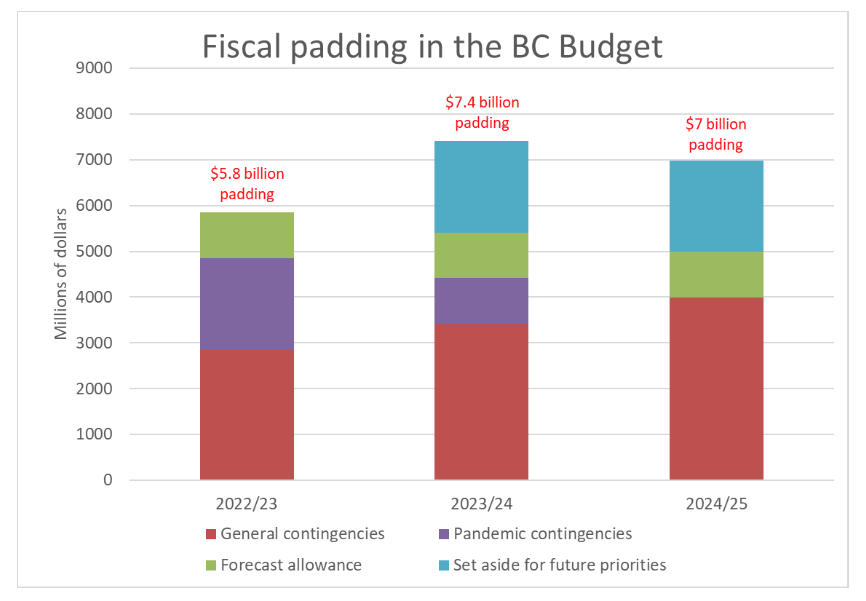

First, there are huge pools of largely unallocated “fiscal padding” built into the BC government’s budget, amounting to $5.8 billion, $7.4 billion and $7 billion each year over the next three years, totalling $20 billion. This swamps the $5.1 billion in deficits projected cumulatively in that time.

These forms of fiscal padding tend to fly below the radar and are rarely reflected in headlines about BC’s fiscal situation. They have long been part of BC budgets—and long been problematic—but they have recently ballooned to multibillion dollar levels each year.

For example, in the current budget year, fiscal padding includes a $2.8 billion general contingency fund, $2 billion contingency for pandemic-related issues and $1 billion forecast allowance. In the following year’s budget plan, there is a $3.4 billion general contingency fund, $2 billion for unspecified “future priorities”, $1 billion forecast allowance and a $1 billion pandemic contingency fund.1

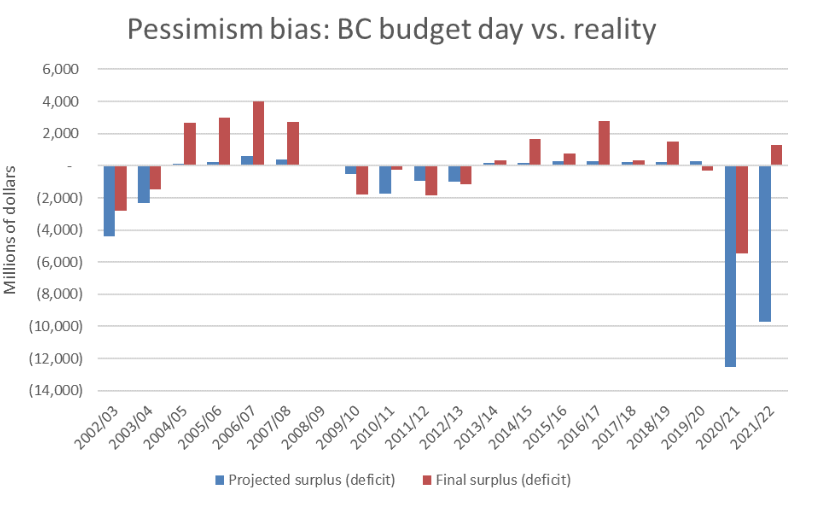

The budget also adds an additional layer of padding by assuming a level of economic growth lower than private sector economic forecasters are projecting, which lowers revenue estimates.

This pessimistic skew in the budget numbers is why you often hear about “surprise” outperformance of budget projections at year-end. In 2021/22, the provincial government originally projected a $10 billion deficit, but by year-end this had turned into a $1.3 billion surplus. For 2022/23, the government originally projected a $5.5 billion deficit, but in its fall fiscal update only six months later it revised this projection to a $700 million surplus.2

To be fair, the pandemic has created plenty of uncertainty, but this practice of budget lowballing is not new. The same pattern has played out in all but a handful of the past 20 BC budgets, with the year-end results turning out rosier than the pessimistic budget-day projections.

In fact, the only exceptions to this pattern were the year of the global financial crisis, the time when BC unexpectedly had to pay back the feds after eliminating the HST, and a small downward revision in 2019/20 at the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Budget lowballing of this kind creates a systematic bias against public spending in BC, distorting democratic debate about the true range of our budgetary and public policy options.

If the goal is to prioritize avoiding deficits above all else, this practice would have some logic to it. But that’s an unwise priority. Whether or not the provincial government runs a balanced budget in a given year is not of any real economic significance. For healthy fiscal management, more relevant long-run measures include the debt-to-GDP ratio (debt relative to the annual income of the economy) and debt service costs (interest payments relative to the size of the budget).

Rather than consistent budget lowballing, BC should set realistic budget projections, recognizing there will be year-to-year fluctuations in both directions. Some years this may mean a larger deficit than expected, sometimes a smaller one, and sometimes a surplus.

More transparent and realistic budgeting would deliver important benefits. First, it would allow us to plan and make policy decisions that are more democratic based on an accurate picture of the resources available. Second, it would dial back the bias against public spending at a time when there is a huge backlog of critical public investments that need to be made.

More transparent and realistic budgeting would deliver important benefits.

Skewing the numbers to avoid fiscal deficits at all costs has meant neglecting mounting social and environmental “deficits”, which has helped create some of the big crises we face today. These deficits in social and environmental investment have been particularly severe for the past two decades since the social spending cuts of the Gordon Campbell government.

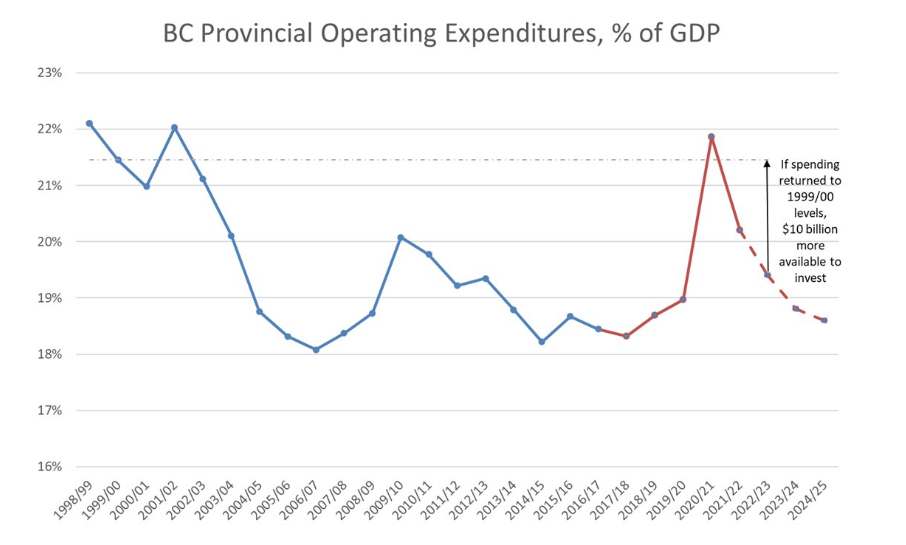

Beyond the year-to-year budget balance, another measure of our capacity to “go big” to meet these big challenges is public spending as a share of our total annual economic output.

Over the past two decades, BC’s provincial government operating spending has declined substantially as a share of GDP, from 21.5% in 1999/00 to a projected 19.4% in 2022/23. In fact, the most recent budget plans for this to decrease further to 18.6% by 2024/25.

Notably, this picture of the decline is conservative because these figures assume that all of the contingency funds put aside for the upcoming fiscal years will be spent in full. If the contingencies aren’t spent, the projected spending levels for these years would be even lower.

To put this in perspective in terms of raw dollars, if BC returned to the spending levels of 1999/00 (as a share of GDP), we would have another $10 billion available to spend on important priorities in the current fiscal year alone (additional to the huge contingency funds discussed above). This figure would rise even further over the next two years.

If we want to increase public spending to tackle big challenges, we have the economic capacity.

How specifically could BC fund increased public spending and investment? Borrowing can play an important role and makes sense particularly when funding highly productive social and physical infrastructure investments. Indeed, some public investments—like a major build out of middle-class rental housing—can largely pay for themselves in a direct way.

Increased public spending can also be funded with more robust taxes on the rich, landowners, and corporations, with the dual benefits of raising revenue and reducing extreme inequality.

Even credit rating agencies—often very conservative institutions—recognize that raising additional tax revenue is well within BC’s capacity. For example, Moody’s notes that: “British Columbia’s level of taxation is at the lower end of the Canadian provinces, presenting the province the flexibility to raise taxes… while still remaining competitive with other jurisdictions.”

Besides being a moral necessity, tackling big social and environmental challenges comes with significant economic benefits. One area where this is now being recognized at the federal and provincial levels is the need for universal child care, but it’s also true across a range of policy areas. The flip side of the coin is that inadequate levels of public investment come at an economic cost. Shortchanging the public sector is economically and fiscally irresponsible.

If we want to increase public spending to tackle big challenges we have the economic capacity.

If social and economic well-being each point to the need for increased public investment, what’s holding us back? Part of the story comes down to power. The status quo works well for the wealthy, who exert disproportionate influence in politics and sometimes block needed action.

Last year when economists, health experts and public opinion aligned in calling on the BC government to implement a minimum right to 10 paid sick days for workers, big business lobby groups were able to push the government to water down its policy to only five days (even as the pandemic was shining a bright light on the need for workers to be able to stay home when sick).

Another example is taxes on the wealthy. Despite enormous public backing for an annual wealth tax on the super rich at the federal level (nearly 9 in 10 voicing support in polling including 83% of Conservative voters), this policy has been nowhere to be seen, even though it would raise significant revenue and help tamp down the troubling rise in extreme inequality.

We live in an incredibly rich society, but too much of our prosperity flows to the wealthiest few, and too little of it is invested in addressing urgent challenges. This disconnect points to the need to build people power through labour organizing, direct working-class representation in politics, and innovations in our democratic system, among other strategies.

Building people power is no small task, but the fact that we have ample economic and fiscal capacity to invest in the common good should be heartening to organizers and bold politicians alike. Meeting this moment of crisis is within our grasp if organized people can overcome the power of organized money, as they have many times in the past.