Articles Menu

November 10th 2019

Countries across the world need to make their 2030 emission targets much more ambitious if the world is to stand a chance of keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, a major research report says.

And Canada is one of the biggest laggards, far from reaching its own targets which are themselves far from enough to keep warming to that level.

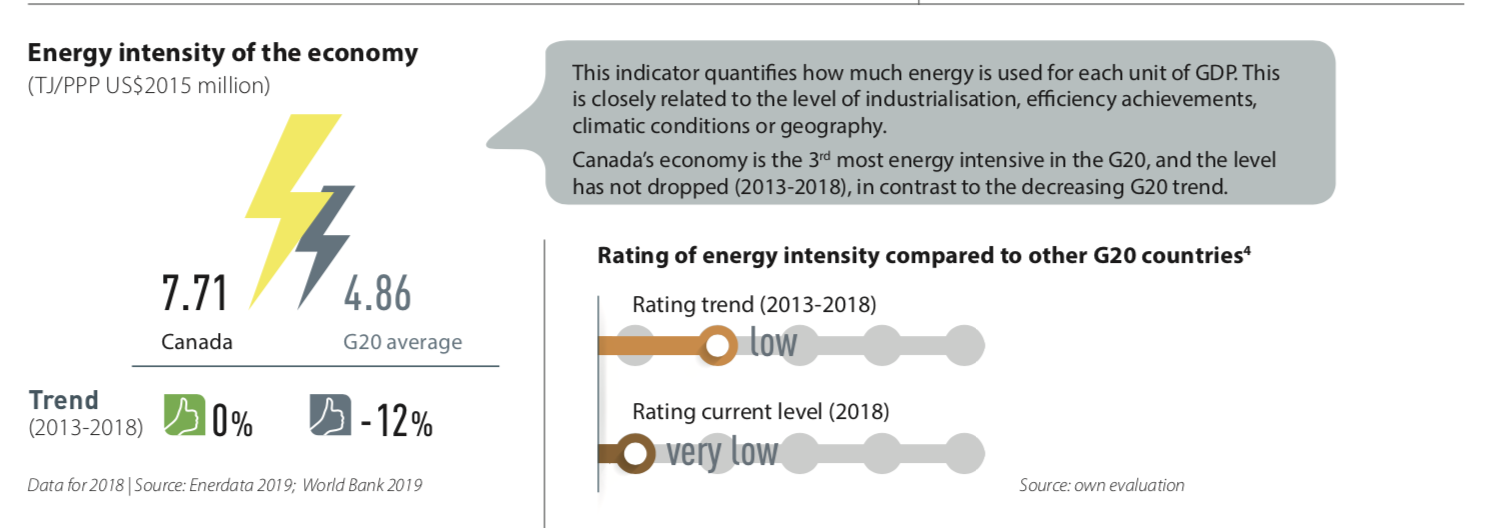

The annual "Brown to Green" report from the Climate Transparency partnership said Canada is far from contributing its fair share toward the 1.5 C goal, with the third most energy-intensive economy in the G20. And that’s despite having one of the cleanest electricity grids.

“South Korea, Canada and Australia are the G20 countries furthest off track to implement their NDCs,” the report said, referring to the nationally determined contributions countries committed to as part of a global response to the climate crisis.

Those goals are due to be updated in 2020.

The report, which its authors call the most comprehensive review of G20 climate action, was developed by experts from 14 research organizations covering most G20 countries, including Climate Analytics, New Climate Institute, and the Energy and Resources Institute.

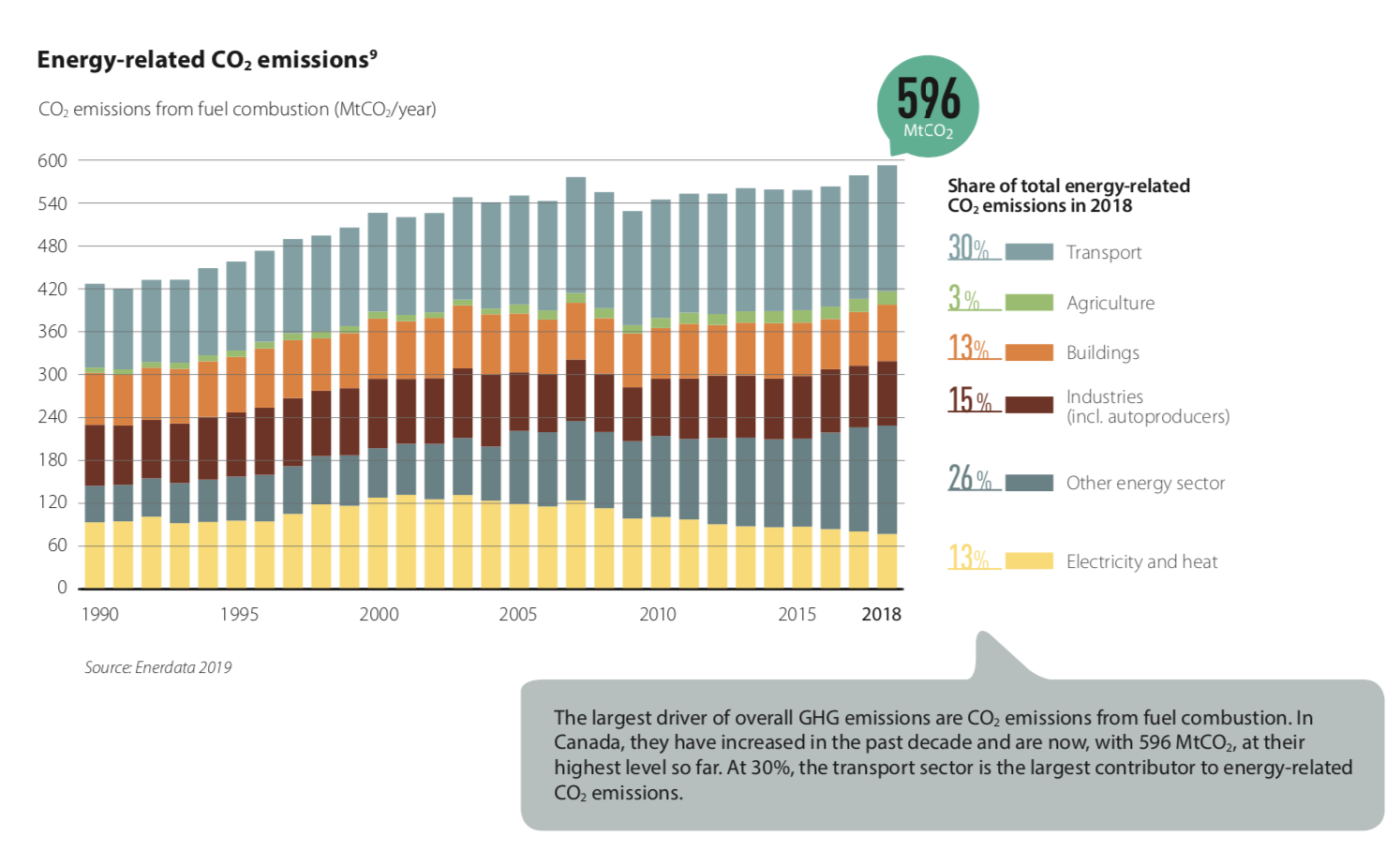

The climate report card on Canada is pretty grim. Canada’s per capita greenhouse gas emissions are much higher than the G20 average, at 18.9 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per person. Much of Canada’s failure to limit overall emissions is due to energy-inefficient buildings and rising pollution from two provinces: Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Those two oil-rich provinces shut out the Liberals and their carbon price in the federal election in October.

Researchers who worked on the Climate Transparency report acknowledged the regional differences that complicate national policy-making.

Canada is one of the biggest laggards in the G20 when it comes to climate action, a new report from @ClimateT_G20 says, with emissions from buildings that are twice the G20 average.

“It is definitely not the same to decarbonize Saudi Arabia, or Alberta in Canada, than it is to become a nice Costa Rica,” said Enrique Maurtua Konstantinidis, from Argentina’s Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Environment and Natural Resources Foundation).

Costa Rica is working to be carbon-free by 2050, with a plan for electric passenger and freight trains in service by 2022, nearly a third of its buses to be electric by 2035, and nearly all cars and buses on the roads to be electric by 2050.

“This brings a lot more challenges. You have a big piece of your economy depending on that ... you have an entire population, or part of society, that was built on that production and you are actually telling them that actually has to be gone very soon.”

Canada will need to have a plan to help oil and gas workers, the report said, similar to what is being set up for dislocated coal workers as that energy source is targeted for a full phase-out by 2030.

The 2019 federal budget proposed a dedicated $150-million infrastructure fund to support affected coal communities, in addition to funding for coal worker transition centres.

Ipek Gençsü from the U.K.’s Overseas Development Institute said that various levels of government must work together to solve these tough problems.

“Not everyone can be retrained, we know that, so it's just having to answer these very real questions,” she said. “But definitely not delaying it and not hiding behind sort of unrealistic scenarios of how much the sectors can continue to provide livelihoods for people, because it's simply not true anymore.”

Canada’s fossil fuel industry accounts for 1 per cent of the national workforce, concentrated in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador provinces.

Yet even Canada’s goal to reduce emissions by 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 is insufficient, the report said, since hitting it would reduce emissions to a range of 518 to 557 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) and Canada needs to get to 327 MtCO2e.

If all countries merely hit their existing 2030 targets, global mean temperature would increase to around 3 C by 2100, said the report, which looked at emissions relating to the production of electricity, transportation, buildings, industry and agriculture.

Keeping the global temperature increase to 1.5 C cuts down the average drought length by more than two-thirds compared to a 3 C rise, limits the growing season’s shrinkage and the reduction of rainfall, and sharply cuts the risk of heat waves that ravage crops.

“G20 countries will have to ratchet up their 2030 emissions targets in 2020 and significantly bolster mitigation, adaptation and finance measures over the next decade,” the report said.

Membership of the G20 consists of 19 individual countries plus the European Union. Collectively, the G20 economies account for roughly 90 per cent of gross world product, and two-thirds of the world population and the world’s land.

Canada could improve its overall performance by adopting a clean fuel standard and enhancing measures to boost zero-emission vehicles, including light and heavy-duty trucks and undertaking deep energy retrofits of existing buildings, a country profile attached to the main 'Brown to Green' report said.

Canada’s emissions from buildings — including heating, cooking and electricity use — make up a fifth of its total CO2 emissions.

On the plus side, Canada has reduced the energy intensity of its buildings by almost 10 per cent between 2013 and 2018, although on a per capita basis they remain more than double the G20 average.

The full report and G20 country profiles can be accessed at the Climate Transparency website.

[Top photo: A man walks between flooded houses in Constance Bay northwest of Ottawa on April 26, 2019. Photo by Kamara Morozuk]