Articles Menu

Sept. 15, 2022

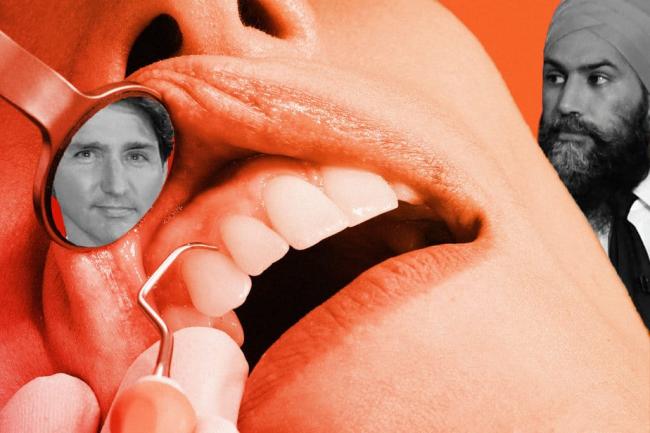

The NDP is hinging their continued support of the federal government on the launch of a dental care program next year. But exactly how the program will be designed—and for whose benefit—remain major questions, and the pressure is on the Liberal Party to provide answers.

What we know so far is that the program will start by ensuring kids under the age of 12 have access to free dental care. To date, the NDP and Liberals have agreed on an interim “bridge payment” of $650 per child annually for two years to low and middle-income parents.

By 2023, it will expand to seniors, people living with disabilities, and minors under 18. The full program—expected to be in place by 2025—will cover all Canadian families earning less than $90,000 a year, with no co-payments for anyone earning under $70,000.

In all, the program is expected to cover between seven to nine million people.

Thirty two per cent of Canadians, around 12 million people, have no dental insurance whatsoever, which means they pay out of pocket to see a dentist. That includes half of all low-income earners and more than half of adults between ages 69 and 79. In 2018, around 22 per cent of Canadians avoided the dentist due to cost.

“It’s absurd that we cover people from the tonsils back,” said NDP MP Don Davies during a Canadian Health Coalition discussion in August. “We have a two-tier US-style access to care—this is something that should be a national shame.”

The program’s design is still up in the air, and everyone from dental care activists to industry associations are keeping careful watch of its development. The federal government has set aside $5.3-billion for the program over the next five years.

The next steps will be crucial in determining the extent to which the program is a boon to the private dental industry—or a challenge to it.

Increased access to dental care is a popular policy across Canada’s political spectrum. A 2020 poll found a majority of voters from the three major parties support a national dental plan.

But some dental professionals are lukewarm on the proposal, which could potentially impact their bottom line.

The Canadian Dental Association (CDA) has expressed support for the federal plan, but not without reservations.

In its June newsletter, the CDA voiced concerns about a “one-size-fits-all-approach” and argued that “difficulties in setting up a new federal program could jeopardize access to dental care for millions of Canadians.” Zelda Burt, communications lead for the CDA, didn’t elaborate when The Breach inquired how expanding dental care could decrease access.

Currently, provinces and territories all offer dental care programs, but they are very tightly targeted—and regularly criticized for being insufficiently funded. The CDA has suggested a new federal program could lead to provinces and territories withdrawing their public funding of dental programs.

The Canadian Dental Hygienists Association (CDHA), Canada’s other major professional dental association, took a much different position than the CDA.

The CDHA supports a national dental program and says there are significant issues with the patchwork of provincial programs. These programs are “limited in eligibility, and fail to recognize dental hygienists as eligible providers, thus restricting accessibility to oral health care,” according to the organization.

Brandon Doucet, a Nova Scotia-based dentist and co-founder of the Coalition for Dentalcare (CFD), takes issue with the view that targeting those deemed “most in need” is the best approach.

For Doucet, the proposed federal dental care program doesn’t go far enough.

The $5.3-billion earmarked for the program will be the largest public investment in dental care in Canadian history, which Doucet says makes it an exciting time to be doing advocacy on the issue. “The higher the rate of public spending, the fewer people avoid dentists due to financial constraints,” he told The Breach.

Doucet wants to see dental care be accessible for everyone, not just the most vulnerable.

Poor oral health can impact other health issues, like cardiac disease or diabetes, worsening one’s livelihood—and stretching the healthcare system.

Advocates for universal dental care like the CFD and the NDP argue universal coverage is not only crucial for improving people’s overall health, but also a more efficient way to deliver healthcare.

Preventative care helps address small problems before they become big and more painful, or even deadly—like stopping cavities from snowballing into root canals, or stopping the spread of gum disease and cancers. Making preventative care more accessible means trips to the emergency room—and expensive and unpleasant late-stage procedures—will become more infrequent.

“Most oral health conditions are largely preventable and can be treated in their early stages,” wrote the Canadian Dental Hygienists Association in a recent submission to the federal government.

One analysis suggested that visits to the ER for dental problems cost British Columbia nearly $155-million in 2017. Dental-related visits represent around one percent of emergency room visits in Canada, even though hospitals are rarely equipped to sufficiently deal with many problems, such as tooth decay.

“The public system will fund someone’s hospitalization, perhaps even for weeks, for a dental infection, but a proactive approach which would be much better for the patient—and better economically—is not available,” said Dr. Amit Arya. “That makes no sense.”

Arya is the palliative care lead at a long-term care home in Toronto, where he sees the consequences of limited dental care first hand.

For some seniors, “food is one of the last pleasures they have left,” but without affordable access to care, their oral health—and ability to enjoy food—suffers greatly, according to Arya. He also pointed out that good oral hygiene helps reduce mortality rates from pneumonia.

Dental care should be part of Canada’s universal healthcare system, he says, noting a big need for dental coverage for seniors and people living with disabilities. “We have few options for people who are poor or living in long term care,” Arya told The Breach.

In the 1960s, dentists successfully fought the inclusion of universal dental care in Canada’s medicare program after it was called for by the 1964 Royal Commission on Health Services, which put medicare in motion.

The NDP is actively advocating for universal access, but it’s not yet on the federal government’s roadmap. According to Doucet, that’s likely a relief for the private dental industry.

“Dental associations want to target low-income children or people with disabilities,” he argued. That kind of targeting, he said, makes programs “politically unstable and easy to undermine.”

“Organized dentistry has been opposed to universal dental care because they worry the fees paid out by those programs will not be high enough and that they will lose autonomy over the profession,” he said.

Government regulation may curb what Doucet sees as excesses of the private profit-led system, like cutting back overtreatment and procedures that are not backed by scientific evidence, or by regulating fee guides, which dictate what dentists can charge for procedures.

A further step in the right direction for Doucet would be public delivery over the insurance-based private delivery model, which most dental care in Canada is currently structured around. Government dentists could even provide care through school programs, which existed in the 1970s and 1980s in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

The CDA’s submission to the 2022 Budget consultation urged Ottawa to “follow a framework of dental care in Canada continuing to be largely delivered by dentists in private settings.”

The extent to which the federal government will experiment with the possibilities of public delivery—or just public insurance—remains an open question.

If the coming program focuses on improving access to private clinics through insurance, it could do so through private insurers or through a public insurance program, which already exists for federal prisoners and Indigenous Peoples with a status card (or recognition from an Inuit land claim organization).

A recent request for information published by the feds garnered the interest of some private insurers. The Toronto Star reported that the first contract is worth $99-million, and the federal government’s commitment of $5.6-billion over five years will no doubt lead to even more lucrative deals should private insurers be included in the plan.

The dental care program is what many call the centrepiece of the NDP-Liberal Confidence and supply agreement (CASA). The NDP say their continued support of the Liberal minority is contingent on getting the program off the ground, with one specific benchmark: extending coverage to children 12 and under in households earning less than $90,000.

Although the NDP initially called on the Liberals to hit that benchmark by the end of 2022 or the party would abandon the CASA, the NDP’s demands have softened in the face of logistical hurdles.

“What we’re hearing is that it can’t be done,” Davies told the Health Coalition webinar in August. “We’re insisting that it must be done sometime in 2023.”

With the NDP temporarily satisfied by the $650 bridge payments, Davies told the webinar his party will continue to support the Liberals as long as a permanent plan is in place by the end of next year.

“I can tolerate a few months, but not years,” he said. If the program isn’t in place by the fall, he says the NDP will walk from the CASA.

An Abacus poll showed strong approval for the CASA, with nearly half of respondents saying they felt it would be “good for Canada.”

The NDP’s stated goal is to push for universal dental care, although the path to achieving that goal is unclear, especially absent the backing of a strong grassroots movement.

“We negotiated what we consider a down payment on universality,” Davies told the webinar.

“The best we could negotiate was to get a start on public coverage, starting with the most vulnerable populations.”

“If we tier it in over time,” he said, the NDP can push to scale up later.

Davies reiterated to The Breach the party’s “commitment to the principle of universality in all health delivery,” which he says is being “achieved incrementally, like Medicare.”