Articles Menu

Feb 23, 2022

A retired developer says the goal of the property industry is to complete new housing supply when it can maximize profits.

“The real-estate development business is very much about market timing,” said Arny Wise, who spent his career planning and developing scores of housing projects in Toronto and Vancouver.

“They want to time it so their development goes to market when the market is good. They don’t want to sell into a crappy market,” said Wise, who does not condemn developers’ practice of aiming to sell houses when prices are riding an inflationary wave. Like other businesses, he said, developers are out to earn profits.

But since politicians in B.C. and Ontario are maintaining that building a massive amount of new housing supply is the solution to lowering astronomical prices, Vancouver-based Wise said they need to recognize reality — “There is no reason to expect developers to accomplish a social good unless (politicians) force them to.”

B.C. NDP Housing Minister David Eby and Ontario’s Conservative premier, Doug Ford, have recently said loosening zoning rules and building far more housing quicker is crucial to solving the housing crisis. The average Canadian house rose in January to $812,000 — a rise of 43 per cent from late 2019 and a jump of 97 per cent from 2015. Prices are much higher than that in Toronto and Metro Vancouver.

But Wise said it is not possible to build housing fast enough to end the unaffordability crisis, unless politicians also address demand by domestic and foreign housing investors. The only way developers will build affordable housing, he said, is if governments require them to when they issue permits.

A University of Sydney scholar goes further than the former developer in monitoring and questioning the phenomenon of “land-banking,” in which properties that could be developed for housing are often withheld from the market in anticipation of greater future gains.

In a peer-reviewed study called Time is Money: How Landbanking Constrains Housing Supply, professor Cameron Murray found that developers don’t necessarily build more housing faster after politicians soften rules and hike zoning density to encourage them to do so.

“The amount of zoned supply in a region is unrelated to the rate of new housing supply,” Murray writes. “Housing developers routinely delay housing production to capitalize on market cycles.”

The Ontario premier is backing a task-force recommendation to build more than 1.5 million homes in the next decade.

But a Bank of Montreal economist, Robert Kavcic, said the target is impossible and ill-conceived, in part because “most of this supply will come to completion after demand has rolled over and the millennial-led demographic boom has peaked, saturating the market for a long, long time.”

Both Kavcic and Wise believe the overpriced housing bubbles of Toronto and Vancouver are due for a crash.

In another paper on what is called the housing-supply “absorption rate,” Cameron explains developers’ logic in delaying housing sales, even if they control an enormous pre-zoned land bank of property.

“Basically, if you sell today, you can’t sell tomorrow. And hence you must ensure you don’t sacrifice future returns, due to higher-priced sales next period, by flooding the market this period,” said Cameron. Sometimes, he said, it’s called land-hoarding.

Developers look for the absorption rate, or “optimal” rate, to put housing on the market, Cameron said. Developers’ annual reports, he said, often point to their strategy of slowly rolling out new housing construction over a long period of time.

“It’s the built-in speed limit on housing development. If it pays to delay and sell next year, that’s what they will do.”

Since Wise, the retired planner, agrees most developers construct at a pace designed to maximize returns and not necessarily to provide a social benefit to the public, he believes politicians must sometimes require them to do so.

He cites how Vancouver’s massive Oakridge Centre development, which will eventually include more than 3,300 homes, mostly condos, has won city approval while only being required to make a fraction of units affordable for renters or buyers.

The asking prices for Oakridge Centre condos currently run at the “insane” levels, he said, of more than $2,000 a square foot.

Wise maintains the city should mandate one third of the Oakridge development, the largest single project in the city in more than 12 years, for low-income families, one third for middle-income earners and one third for “high rollers and investors.”

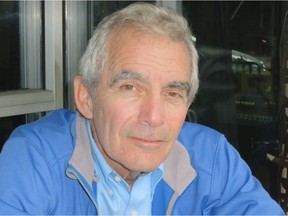

[Top photo: Housing developers try to make sure they don’t sacrifice future financial returns by flooding the market with housing during just one period, says housing professor Cameron Murray. PHOTO BY MARK VAN MANEN /PNG]