Articles Menu

The fifth anniversary of the Mount Polley Mine Disaster has come and gone. Will Mount Polley Mining Corporation or its parent company, Imperial Metals, ever be charged for their role in one of the worst mine disasters in Canadian history?

While the company might still face charges through indictment (a more serious process), the deadlines for charges under BC’s Environmental Management Act and for summary charges under Canada’s Fisheries Act have passed.

This seems an ideal time to revisit a long-time concern of West Coast Environmental Law – BC’s low rates of environmental enforcement. We last blogged about this in 2016 when we had enforcement data to 2014. We now have data to the end of 2018 on the Ministry of Environment’s compliance efforts under BC’s main anti-pollution law, the Environmental Management Act (the EMA). There’s good news and bad news.

The good news: the Ministry of Environment is making effective use of the new administrative penalty tools under the EMA. The flexibility of administrative penalties means that there has been a modest increase in the number of polluters facing significant penalties for violating the EMA.

Also, the government is being more transparent in its release of data, which allows us to confirm the bad news.

The bad news: overall industry compliance with the EMA continues to be low, and the government continues to treat that non-compliance with kid gloves. We’ll be making recommendations about how the government can up its game – and hold polluters accountable when they violate the law.

The good news - Increasing serious enforcement under the Environmental Management Act

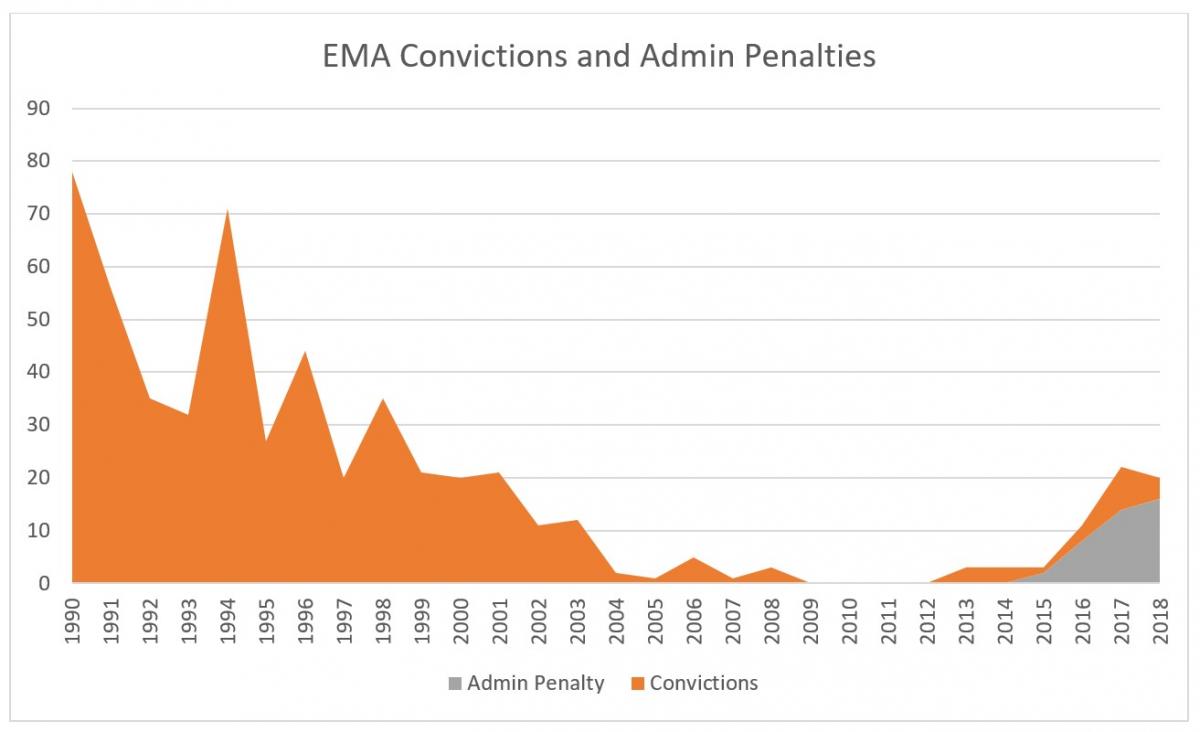

Enforcement action taken under the EMA has dropped dramatically over the past two decades. The collapse in the number of charges laid and convictions obtained has been of special concern. Instead of laying charges, officials have often relied on less serious enforcement actions such as issuing tickets, but these actions typically involve only small penalties – perhaps several hundred dollars – that do not reflect the potentially huge profits to be made by companies that cut corners.

However, in 2014 the BC government passed a regulation giving itself administrative powers to penalize offenders under the EMA. We were pretty stoked, since we’d been recommending these types of powers since at least 1997. Administrative penalties are issued by the Ministry of Environment – not by courts – but they involve more process and much bigger penalties than a simple ticket (potentially in the tens of thousands of dollars).

It seems that the government’s use of administrative penalties is picking up at least some of the enforcement slack. The chart below shows the number of convictions and administrative penalties under the EMA from 1990 to 2018.*

If you treat administrative penalties as equivalent to convictions (they are not, but the two are much closer than, say, tickets), in 2017 twenty-two offenders had a significant penalty levied against them. While that’s lower than the 42 convictions per year that were the average for the 1990s, it is the highest level since 1998 and far higher than the average of five convictions per year since 2000.

We believe that there are many more offences that deserve convictions or administrative penalties, but it appears (at least so far) that administrative penalties are not replacing the use of charges/convictions. In 2017, there were eight convictions under the EMA, which is the highest number since 2003. Although there were only four convictions in 2018 (and a record 16 administrative penalties), that is still more convictions than many of the past 15 years.

The good and the bad news about inspections

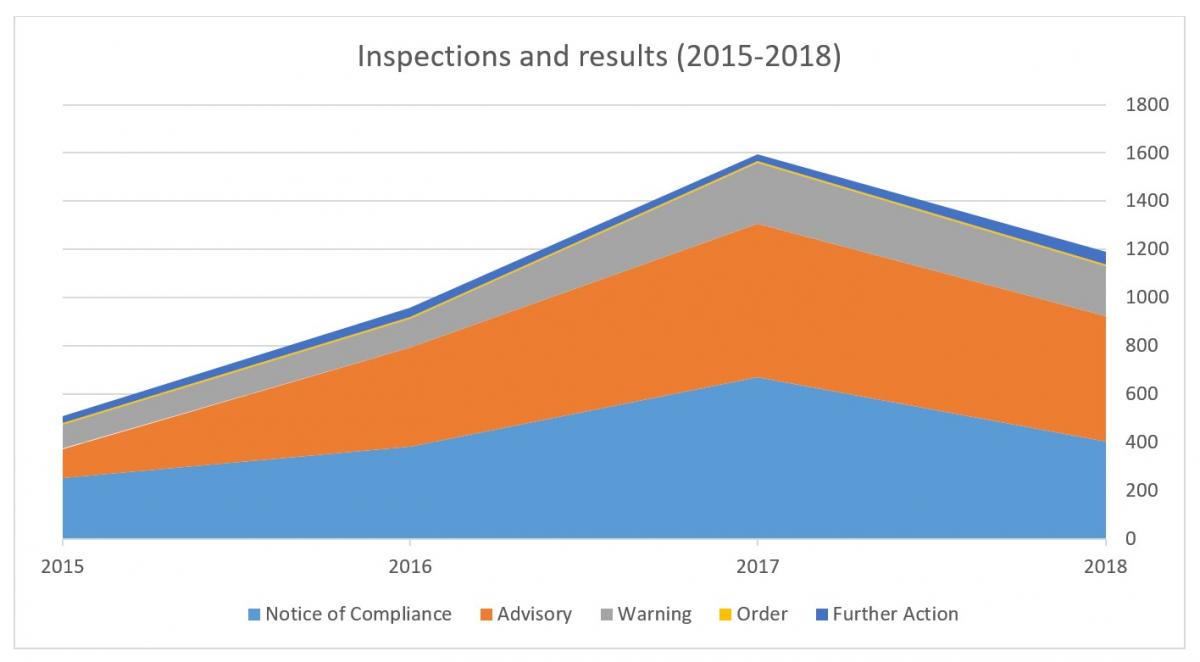

In 2015 the Ministry of Environment began releasing information on compliance inspections carried out under the Environmental Management Act, and starting in 2018 this data and data about specific inspections has been incorporated into the government’s Compliance and Enforcement Database. Consequently, we can now comment on EMA enforcement within the context of how often the government detects violations of the EMA.

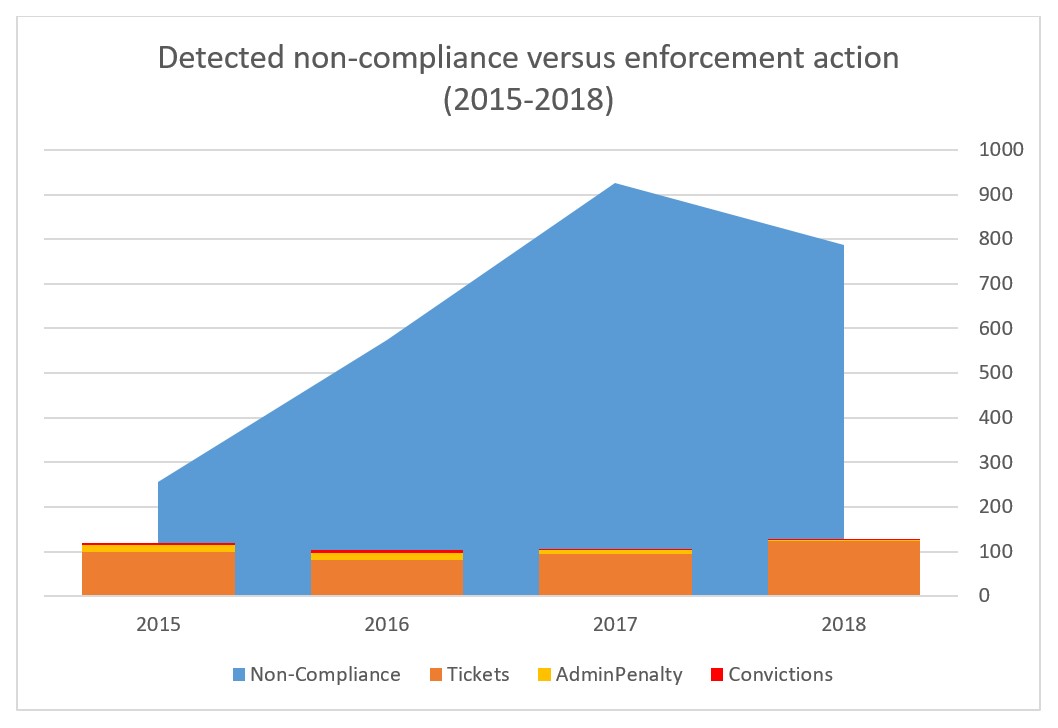

In our view, the inspection records demonstrate a reluctance to take enforcement action – and raise concerns that there may be a high level of non-compliance with the Environmental Management Act.

What the inspectors found

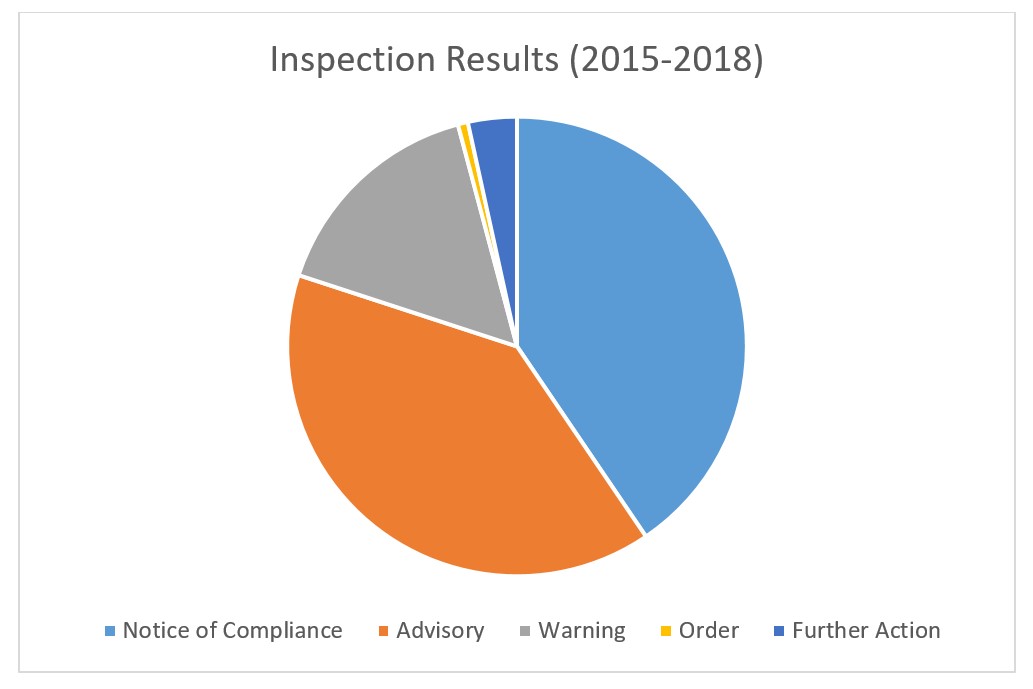

Each inspection listed the result in the data records. Overall the inspectors found some level of non-compliance with the EMA in about 60% of inspections, but the vast majority of those were dealt with through written statements with no direct consequences.

If the inspectors found full compliance with the relevant provisions of the EMA (yay!!), they wrote up a “notice of compliance.” The four years of available data show that this occurred 40.6% of the time.

However, if the inspectors found non-compliance, they had a choice about what to do – similar to the choice facing a police officer after stopping a speeding car.

The most common action taken by Ministry of Environment investigators who find non-compliance is to “advise” the offender that they are violating the EMA, and perhaps give some advice on how to get back into compliance. This occurred 39.6% of the time.

The next most common compliance action taken is to issue a “warning” – setting out possible legal consequences if the non-compliance continues. This occurred 15.9% of the time. Neither “advisories” nor “warnings” by themselves carry any consequences, and the main difference seems to be that warnings emphasize possible future consequences.

The Government’s Compliance and Enforcement Policy and Procedureexplains:

An advisory notifies the non-compliant party in writing that they are not in compliance with a specific regulatory requirement and often recommends a course of action that is expected to achieve compliance. … [A] warning differs from an advisory in that it warns of the possibility of an escalating response should non-compliance continue.Warnings are generally used when it is determined that an exchange of information alone would not be sufficient in achieving compliance. [Emphasis in original]

A very small number of inspections (about 0.7%) result in the issuance of an “order,” which could be a pollution prevention order to address risk to human health or the environment, but more often is simply an order to comply with the EMA. It is an offence under the EMA not to follow an order.

Finally, 3.44% of inspections resulted in a referral of the case to other Ministry of Environment officials for possible tickets, administrative penalties or charges.

While the numbers above appear to show that 59.4% of EMA-regulated facilities are out of compliance, we cannot draw this conclusion. Inspections are often carried out because there is a reason to believe that there may be non-compliance, in which case the detected rate of non-compliance will be higher than the average rate. For example, going back to visit the same non-compliant site on more than one occasion is a good thing – but each inspection is recorded separately, so doing so increases the percentage of non-compliant inspections unless the offender has corrected the problems.

At the same time, however, it is alarming that there were so few serious penalties despite the thousands of inspections that found non-compliance. In a four-year time period, only 46 convictions or administrative penalties (plus 397 tickets with fines of a few hundred dollars each)** were issued, while inspectors conducted 4,271 inspections and found 2,543 instances of non-compliance.

As we have written previously, the EMA primarily regulates industrial pollution, not cases of littering by individuals. When it comes to issuing tickets and fines, the financial penalties for companies are often minimal:

Would a ticket for $575 convince someone who is disposing of industrial toxic waste in contravention of the Environmental Management Act not to reoffend? The Environmental Management Act offenders are much more likely to be businesses that make a significant amount of money from operations that cause pollution. As such, it’s much, much harder to argue that a $575 ticket is sufficient.

People who are engaged in industrial processes need to know what the legal requirements are and ensure that they are in compliance. A simple request to remedy the situation – the most common type of regulator response – is unlikely, in our view, to act as a deterrent for non-compliance.

A deeper dive into advisories and warnings

We all have a sense of what it means to be let off with a warning, but what does it mean to get an “advisory”? The value of advising a person that they have broken the law, as opposed to warning them of possible consequences, is unclear. Shouldn’t every person who is breaking the law be warned that continued violations may result in legal action? In our view, the distinction needs to be scrapped.

According to the “Non-Compliance Decision Matrix” in the government’s policy and procedure document (at p. 19), advisories are supposed to be used where the violation’s risk to human health is low and there is a low likelihood of re-offence.

Unfortunately, a review of some of the inspection data suggests that Ministry staff may be downplaying the risks and likelihood of re-offence.

Case study: Canadian Natural Resources Ltd.’s record of inspections

Consider the oil and gas company, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. All of its nine EMA-related inspections between 2015 and 2018 resulted in advisories. The only public advisory is from 2018, concerning the company’s failure to provide test results (and possibly to do the testing) to ensure that a camp waste water treatment facility was not causing groundwater contamination.

However, a 2019 inspection of the same company resulted in a warning, this time for widespread non-compliance at a secure landfill for industrial waste soil. The inspection found:

According to the Inspection Report, the inspector believed that there was a low risk to the environment and human health and a relatively high probability of future compliance.

This assessment is questionable, given CNRL’s nine previous instances of non-compliance between 2015 and 2018. In addition, it appears that hazardous waste water was actually discharged into the environment. While the actual level of impact on the environment or human health may be unknown, it should be presumed that when legal provisions that are intended to prevent significant environmental and human health impacts are breached, that those types of impacts will occur.

What do you think? Was a warning appropriate in this case? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below.

Looking at other companies with many non-compliant inspections, it appears that at least some of them are now facing administrative penalties and even court convictions. For example, Teck Coal had 177 inspections from 2015-2018, resulting in 41 notices of compliance, 97 advisories, 25 warnings and 14 referrals for further action.

Up until early 2017, the only penalties the company had received under the EMA were five tickets totalling $2,875 (they had also received a ticket under the Water Act for $230). However, in 2017 and 2018, they had:

This is still arguably small change for such a large company, but the company also faces some recent Fisheries Act charges. Perhaps the times are a-changing.

Recommendations and a challenge

I have a challenge for any particularly keen readers and some recommendations for the Ministry of Environment.

First, the challenge. Dig into the Environment and Compliance Database and read some inspection reports. Give us your thoughts in the comments section below. Or, even better, share your thoughts in a letter to the Minister of Environment.

We have made a number of higher level recommendations to the government over the years on how to solve the crisis in environmental enforcement, such as increasing the consequences of non-compliance, ensuring adequate staffing and coordinating with other law enforcement offices.

After reviewing this data, we have three very specific recommendations for Environment Minister George Heyman related to the Ministry’s current approach to enforcement.

It might be tempting to believe that the government’s failure to charge Mount Polley Mining Corporation with violating the EMA was unusual. Unfortunately, after reviewing the enforcement trends, it seems unique only in the amount of media coverage the disaster has received. Our friends at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives have recently written on the poor enforcement by BC's Oil and Gas Commission. Moreover, as we’ve observed recently, the Canadian government has also failed to effectively enforce the Fisheries Act (and Mount Polley is, so far, a further example of that too).

Both the federal and provincial governments need to up their game on environmental enforcement – so that industrial polluters know there will be consequences if they don’t follow the law.

* - Note that our raw data from before 2006 listed charges, not convictions, which prior to 2006 were primarily charges under the EMA’s predecessor, the Waste Management Act. In converting them to convictions, we have assumed that any charge that is listed as resulting in a penalty involved a conviction. The Ministry of Environment has disputed our conviction figures, but has never provided alternative figures. Certainly, since charges are only supposed to be laid where there is a likelihood of a conviction, we are confident that the general trend we report is correct.

** - To be clear – the inspections from 2015-2018 did not necessarily result in these particular penalties. While tickets can be issued fairly quickly, administrative penalties and convictions may take months or years to materialize, so offenders that were referred for further action in 2018 almost certainly have not yet had their penalties/convictions confirmed.