Articles Menu

Apr. 3, 2024

On Feb. 20 John Pomeroy, the Alberta-based director of Global Water Futures at the University of Saskatchewan, journeyed to British Columbia’s Okanagan Basin, a place of vineyards, orchards, pleasant cities and recreational playgrounds, to deliver a message.

Pomeroy came armed with the latest projections for how climate change will dry up the region. His presentation included predictions of drained reservoirs and increasingly flammable forests.

Global Water Futures, a pan-Canadian research team consisting of more than 200 academic researchers at 23 universities, strives to predict water futures with computer models. These models are regularly verified by real-time field data on the changing state of snowpacks, soil moisture, streamflows and rainfall patterns in Canada’s seven major water basins. The goal is to help communities adapt to climate change by managing risks including fires, droughts and floods.

A 2006 paper by water ecologist David Schindler and environmental researcher Bill Donahue that warned about an impending collision between historic drought, climate change and bad water management in Western Canada helped to spur the Global Water Futures group into existence.

Pomeroy’s Okanagan presentation to attendees of the Southern Interior Horticultural Show was not, as he put it, “the easiest information to share.” And the audience was already depressed.

In January an extreme polar vortex had killed budding grapes, destroying more than 90 per cent of the wine crop. Grape and cherry growers, already reeling from the 2021 heat dome that pushed the thermometer to 47 C in some parts of the Okanagan, talked about “catastrophic loss and stunned disbelief.”

Last year’s long, mild fall and early winter had filled orchard trees and vines with rising sap. Then the temperature abruptly fell more than 20 C overnight. In one orchard, the temperature plummeted from 2 C to -23 C in half a day.

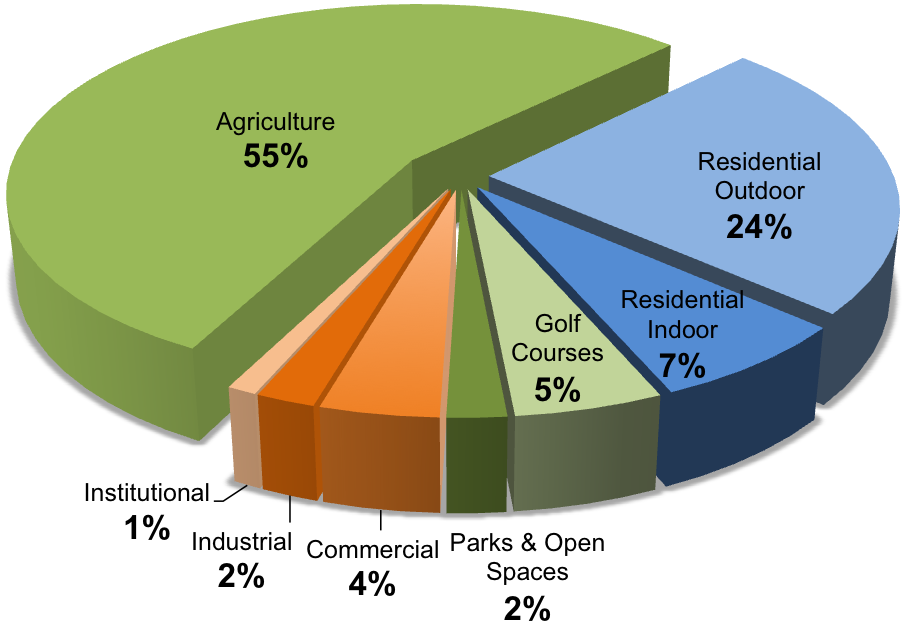

Long-term climate trends provide more reason to worry for Okanagan growers, given that over half of water allocations in the basin go to irrigated agriculture.

The region’s deep lakes can make it seem water blessed. Indeed, two-thirds of the water its human inhabitants depend upon comes from lakes and streams. But the Okanagan is going to get drier as climate change rearranges the timing and volume of water nourishing it.

“Central B.C. is predicted to get larger temperature increases but more modest precipitation increases than most of Canada this century,” Pomeroy told The Tyee, echoing what he shared in his presentation.

The mountains in the Okanagan are not nearly as high as the Rockies and are therefore more vulnerable to higher temperatures. Okanagan mid-winter snowpacks that averaged 100 millimetres of snow water equivalent will drop to 60 millimetres by mid-century.

That means streamflows will drop precipitously in the months of April and May when the spring freshet has historically recharged groundwater, soils, ponds, lakes and reservoirs for summer use by native vegetation, agricultural interests, golf courses and municipalities.

By 2050 the Okanagan’s average temperature in July could rise to 28 C from 18 C.

“That shift is really high and moves the Okanagan closer to a Mediterranean climate,” added Pomeroy. And by Mediterranean he means something like the most arid parts of Spain’s Andalusia rather than the balmy, subtropical clime of Cannes, France.

The water supply problem faced by Okanagan irrigators is one of both timing and volume. There will be less snow to melt. And it will disappear much earlier in the season, as most precipitation will come as rain.

Given higher temperatures, spring melt will occur a month earlier, changing peak streamflow from April to March. The volume of water runoff will fall between four per cent and 31 per cent in the basin by 2050. “That is quite a concern because it will be hotter with much less water,” explained Pomeroy.

The loss of snowpacks and their replacement by erratic rainfalls “will cause tremendous problems. There won’t be enough water to refill lakes and wetlands,” the hydrologist predicted.

What does it mean that the Okanagan region will face not only more variable water supplies but less water altogether?

The shift, said Pomeroy, “will challenge current water resources management, municipal and agricultural practices, and require substantial adaptation based on improved predictions and forecasting and adaptive management of water use and crops.”

But residents in the Okanagan, like most people in Canada, aren’t adequately prepared for a hotter and drier future, Pomeroy said.

“We have never had a big water challenge in Canada where we had to manage water differently. It’s going to make it challenging to decide who gets the water, when do they get it and who can’t have it. That’s going to be a tough one for us. Canada’s never faced that before.”

Yet the scenario Pomeroy presented to his audience has been long forecast.

A 2010 report funded by the Okanagan Basin Water Board noted that winter snowpacks will decrease as the climate warms, that snow levels will move higher up the mountains or disappear altogether and that opportunities for storage would be limited given the shift from snow to rain and the timing of that rain.

“Further, agricultural water demands are expected to increase as climate change creates hotter summers and longer growing seasons,” wrote the researchers 14 years ago.

A Tyee report published 18 years ago headlined “Drying Up the Okanagan” called the region “the ‘canary in the coal mine’ for B.C. and water.”

Drawing on experts, reporter Chris Wood noted that “even as our enviable environment attracts more and more people, and British Columbians waste more water per capita than almost anyone else on the planet, a warming climate is tending to deliver less and less winter snow.”

[Top photo: John Pomeroy crunched sobering data. ‘It’s going to make it challenging to decide who gets the water, when do they get it and who can’t have it.’ Photo via University of Saskatchewan.]