Articles Menu

Dec. 2, 2022

This story was originally published by The Guardian and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration

In the early 1990s, vultures across India started dying inexplicably. Long-billed, slender-billed and oriental white-backed vultures declined to the brink of extinction, with the number of India’s most common three vulture species falling by more than 97 per cent between 1992 and 2007. Six other species were in sharp decline, too. Scientists started testing the dead birds and worked out they had been exposed to diclofenac, an anti-inflammatory drug routinely given to cattle in South Asia at the time. The vultures fed on the carcasses of cows and were poisoned.

The Indian Vulture (Gyps indicus) or Long-billed Vulture in flight. Photo by Deepak sankat/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

That was the beginning of a far-reaching chain reaction. As vulture populations crashed, cow carcasses started to pile up, and the numbers of rats and wild dogs surged. Dogs became the main scavengers at dumps previously used by vultures. Data suggests that from 1992 to 2003, dogs increased by seven million. The number of dog bites soared and rabies infections shot up, causing tens of thousands of people to die each year. In 2006, diclofenac was banned, and vulture populations have slowly started to recover.

In the late 1950s, China’s leader, Mao Zedong, wanted to rapidly industrialize the country through the Great Leap Forward. That involved the “four pests campaign,” targeting mosquitoes, rats, flies — and sparrows. He ordered all the country’s sparrows to be killed because he thought they were feeding on rice and grains and reducing the amount available for people. Citizens were told to shoot the birds, tear down their nests, smash their eggs and bang pots so they would be scared into the sky and fall to their deaths, exhausted. Sparrows were nearly driven to extinction in China.

What Mao’s officials didn’t realize is that sparrows rely on grains for only a small part of their diet: the bulk of it comprises insects. After the mass killing, there was an eruption of insect pests which destroyed the country’s crops. “This ecological catastrophe coupled with a multi-year drought and disastrous agricultural policies led to one of the most devastating famines in history. It is estimated that about 45 million people died,” says Prof. Marc Cadotte, an ecologist at the University of Toronto.

A deadly chytrid fungus called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) ripped through Panama and Costa Rica from the 1980s to the mid-1990s, leading to the extinction of dozens of species of amphibians, with some scientists putting the number at 90. It was described as “the greatest loss of biodiversity attributable to a disease,” but most people would have been unaware of the tragedy.

What happens when #humans meddle with nature? #ClimateChange #environment #ClimateCrisis - twitter

Panamanian Golden Frog — Atelopus zeteki. Photo by Brian Gratwicke/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Panamanian Golden Frog — Atelopus zeteki. Photo by Brian Gratwicke/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

After the deaths, there was an eight-year spike in malaria cases in Central America, as mosquitoes thrived, probably because there were no frogs, salamanders and other amphibians to prey on their eggs, researchers reported recently. At its peak there was a fivefold increase in malaria cases.

“If we allow massive ecosystem disruptions to happen, it can substantially impact human health in ways that are difficult to predict ahead of time and hard to control once they’re under way,” says Michael Springborn, a professor at the University of California, Davis, and lead author of the paper.

In 2004, an Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami killed more than 230,000 people. The countries worst hit were Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and Thailand, all of which had experienced significant declines in mangrove cover, according to a report by the Environmental Justice Foundation. From 1980 to 2000, the area covered by mangroves in these countries fell by 28 per cent. In places where the trees had been destroyed, the waves penetrated further inland, killing more people and aggravating the destruction of homes and livelihoods. The “mangrove forests played a crucial role in saving human lives and property,” the report said.

Mangroves absorb the impact of waves and rising sea levels by their large root systems, which dissipate energy. “Conserving and restoring coastal mangrove areas is essential if coastal communities are to recover and be protected from similar events,” the report concluded.

In Sichuan province, southwest China, the widespread use of pesticides alongside habitat destruction means that farmers have to carry pots of pollen to pollinate pear and apple trees themselves, according to Dave Goulson, professor of biology at the University of Sussex. This means using a paintbrush attached to a long bamboo pole to dab inside each flower. About 30 per cent of China’s pear trees are artificially pollinated, according to one study.

Pollinating insects are vital to human food security — three-quarters of crops depend on them. They are also crucial to other wildlife, as a source of food and as pollinators of wild plants. But a lack of wild pollinators is affecting food production around the world. In the US, researchers studied seven crops grown in 13 states and found that five showed evidence that a lack of bees is affecting the amount of food that can be grown, including apples, blueberries and cherries.

Since the Second World War, our main defence against crop pests has been artificial pesticides. But these chemicals also kill helpful insects, including parasitoid wasps, lacewings and ladybirds, which hunt common pests and provide support to farmers and gardeners.

Researchers in Brazil have found that ants can be more effective than pesticides at helping farmers produce food because they are better at killing pests, reducing plant damage and increasing yields. This is because they are “generalist” predators, hunting pests that damage fruit, seeds and leaves. The scientists looked at the impact of 26 species of ants (mainly tree ants) on 17 crops, including citrus, mango, apple and soy. According to the paper, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, they do best in diversified farming systems, such as agroforestry and shade-grown crops because there are more places for them to nest.

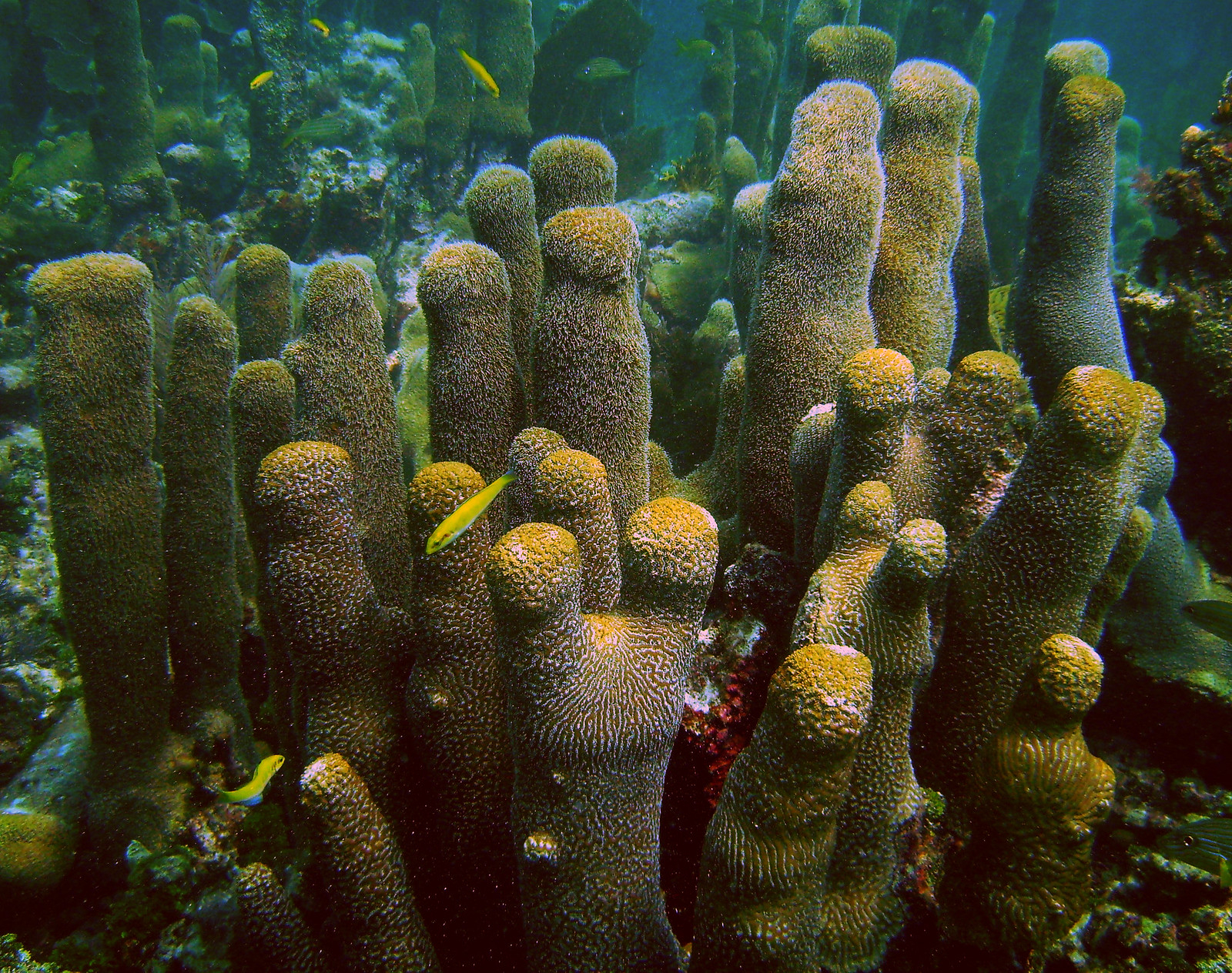

Like mangroves, coral reefs are a natural barrier to waves and storms. Because of their hard, jagged formations they can protect coastal communities and reduce the threat of erosion. They make it more likely for waves to break offshore, reducing wave energy by an average of 97% by the time they hit land. It is estimated that nearly 200 million people in coastal areas around the world depend on the protection of coral reefs. Research shows that in the U.S. they provide more than $1.8 billion annually in flood protection benefits.

Corals and blue-headed wrasse at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary reef. Photo by National Marine Sanctuaries/Flickr-Bill Precht/NOAA

However, developments such as marinas and docks, as well as pollution, damage these reefs. The corals are also being destroyed by rising temperatures, which lead to mass bleaching. Research suggests that virtually all corals on the planet will suffer from severe bleaching if global temperatures rise by 1.5 C.

[Top photo: In the early 1990s, vultures across India started dying inexplicably. Scientists started testing the dead birds and worked out they had been exposed to diclofenac. A flock of vultures on carcass. Photo by Arindam Aditya/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)]