Articles Menu

Mar. 7, 2024

[Editor’s note: An original, longer version of this article is published today by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, where the author is a policy analyst.]

Environmental leaders and a former high-ranking civil servant call it a betrayal in the making.

For months, officials in the Ministry of Forests have been working on a map that significantly departs from the recommendations of a panel appointed by the provincial government to advise it on how to protect British Columbia’s imperilled old-growth forests.

The map suggests that behind the scenes, bureaucrats in the ministry are undoing the work of the panel and freeing up as much old-growth forest as possible to be cut down.

The leaked mapping data, which was contained in a password-protected file on a ministry file-sharing website until a few hours after this story was published*, reveals that ministry bureaucrats have rejected more than half of the proposals made by the panel to defer logging of some of the biggest and best remaining old-growth trees in the province, a move that clearly favours the logging companies that the ministry regulates.

“What’s happening behind the scenes is sabotage. The science clearly states we need to protect what little old growth is left, yet our timber-friendly Forests Ministry wants to scuttle those plans,” says Michelle Connolly, director of Conservation North, a volunteer organization dedicated to protecting the northern interior’s dwindling old-growth and primary forests.

“It’s vital that Forests Minister Bruce Ralston and Premier David Eby put a stop to this. Otherwise, it’s a betrayal of the public trust,” Connolly added.

The mapping data, which was sent anonymously to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, reveals a pattern that appears to ignore much of the advice given to the government nearly three years ago by a five-person technical advisory panel consisting of two biologists, two professional foresters and one non-governmental organization rep.

The panel explicitly flagged how few old-growth forests remain after more than a century of intense commercial logging, and of those that are left, the rarest of the rare are those old-growth forests with the biggest trees.

“Big-tree old growth is naturally rare at the provincial scale,” the panel warned the provincial government in October 2021, adding that what remains “is threatened because it continues to be targeted for timber harvesting.”

The panel’s report built on an earlier Old Growth Strategic Review written by Al Gorley and Garry Merkel, two respected professional foresters.

That review, received by the government four years ago, noted that “a paradigm shift” in public attitudes toward the environment has occurred and that the province must respond accordingly.

After receiving the Gorley and Merkel report, the government appointed the technical advisory panel to help guide it as it developed a new plan that would both identify at-risk old-growth forests and “transform” the way such forests were managed.

The panel’s terms of reference noted that the new management regime would include “more permanent conservation measures.”

But that instruction is being ignored by Ministry of Forests bureaucrats who have been busy redrawing the map that the panel submitted to the province in October 2021.

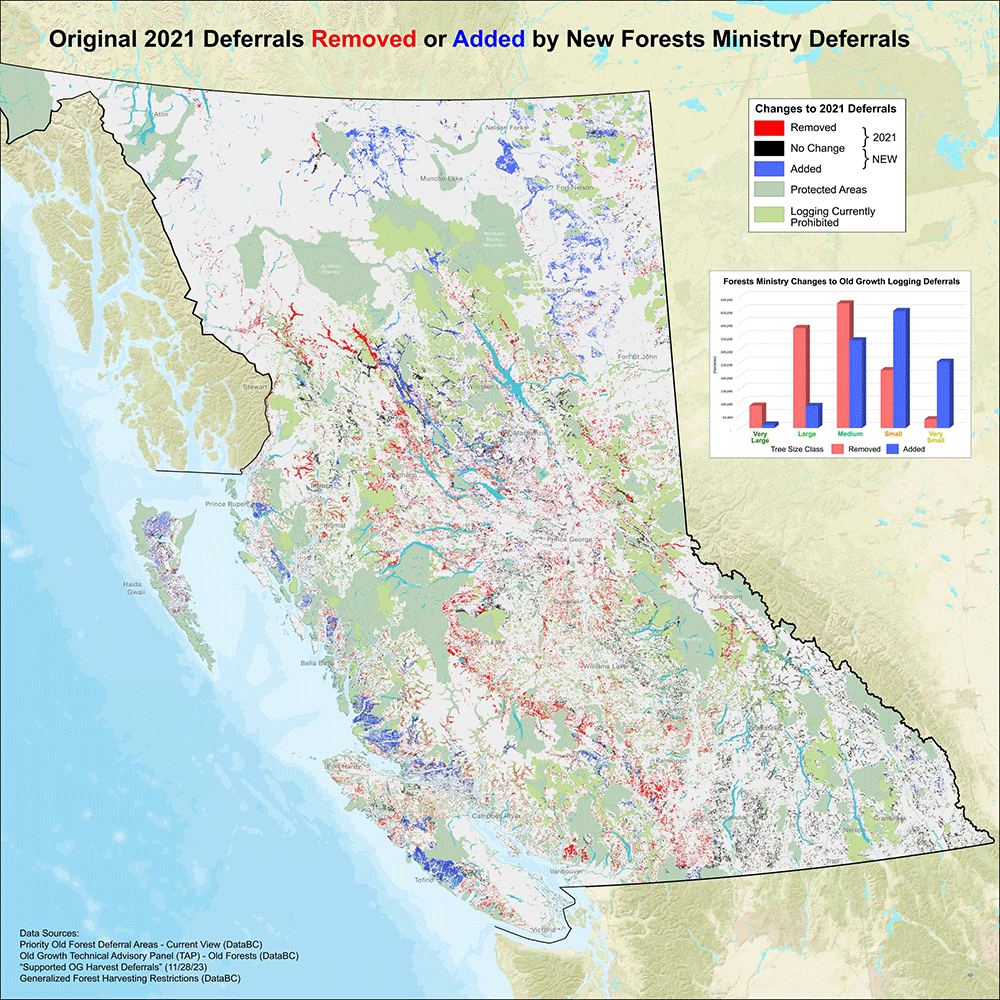

After receiving an anonymous letter with a copy of the password-protected file, the CCPA asked David Leversee, a mapper with extensive experience analyzing forest cover data, to compare the ministry’s map with the proposed old-growth logging deferrals the panel submitted to the government.

The analysis reveals sweeping changes, the biggest being that ministry bureaucrats removed more than half (55 per cent) of the areas of large- and very large-treed old growth that the panel recommended be deferred from logging.

The analysis, which used the same tree size data as that used by the panel, also revealed that ministry officials substantially increased logging deferrals in other areas with smaller and less commercially valuable trees. This included doubling deferrals in older forests with small trees and increasing by a factor of six deferrals in older forests with very small trees.

The outcome: massive areas of forest containing the very best old-growth trees ended up back in the logging column while deferrals increased in forests of little or no commercial interest to the logging industry.

According to the leaked data, the ministry’s revised map indicates “supported OG harvest deferrals.” OG stands for old growth, while harvest is the ministry’s euphemism for logging.

Not named is who the supporting party or parties are, although it seems clear that logging companies were consulted by the ministry or, at the very least, kept front of mind.

“At risk is the very best of what’s left of our ancient forests throughout the province,” says Vicky Husband, who was appointed to the Order of Canada in recognition of her conservation efforts. “Shockingly, that includes Vancouver Island where valley after valley of ancient cedar, spruce, hemlock and Douglas fir forests have been destroyed. The ministry’s backroom dealings are a breach of public trust, and the B.C. government must stop it before the last of the great giants fall and we lose our ancient forest legacy.”

Further analysis of tree height reveals that the blocks of old-growth forest containing the very best trees that ministry officials removed from deferred status cover a combined 550,000 hectares of land.

That is an area in excess of 680,000 football fields, which represents between five and six years’ worth of supply for an industry that has logged itself into a corner by cutting down too many trees too quickly.

The analysis also reveals that at the same time that the ministry moved a small amount of big-treed old-growth deferrals into areas not recommended by the panel, it also moved a massive amount of “supported” deferrals into areas dominated by small and very small trees.

In some cases, those new small-tree deferrals include areas of forest of negligible or no economic value to the forest industry.

For example, the ministry’s new deferrals take in windswept coastal forests of Rivers Inlet on B.C.’s central coast, forests whose stunted trees have not been logged for a reason: they have no commercial value.

Similarly, in northeast B.C., the ministry’s “supported” deferrals include more than 206,500 hectares of black spruce forest. That is an impressive amount of land, equivalent to more than 255,000 football fields in size. But it is of zero significance to the logging companies that have never shown an inclination to log such forests.

The comparison of the panel’s map with the ministry’s map also reveals some clear regional variations.

Generally, the vast central interior region of the province stretching from Hope in the south to Prince George and beyond in the north has been most opened up to logging as a result of the ministry’s behind-the-scenes manoeuvres.

This includes greenlighting logging the last vestiges of unprotected old-growth forests in the globally rare interior temperate rainforest, which a team of international scientists warned is on the verge of ecological collapse.

The logging industry-friendly changes also take in further bands of land in the interior of the province that sweep to the east of Prince George before arcing north into the forests in the distant Stikine region, and west and then north of Prince George to the Peace region near the community of Dawson Creek.

Portions of heavily logged Vancouver Island and B.C.’s south coast are also not spared, with the ministry map showing potential for many remnant old-growth forests to be cut down.

Generally speaking, the areas of B.C. where the panel’s proposed logging deferrals remain largely unchanged or have been augmented with increases are the north and central coast, portions of the Kootenay region in the southeast of the province, the Clayoquot Sound region on Vancouver Island and the Peace region north of Fort St. John.

The increases in the Peace region likely stem from a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of British Columbia, which found that the treaty rights of the Blueberry River First Nations were violated because the provincial government failed repeatedly to consider how cumulative industrial developments would so fragment the landscape as to deny the nations their treaty-protected rights to hunt, fish and trap.

Anthony Britneff, a longtime public servant who worked for 40 years for the Ministry of Forests in a number of senior professional positions, believes that the ministry has a deeply entrenched timber bias, as he wrote in a recent commentary.

That bias, he says, is evident in the map the public has until now not seen. He is concerned that as the ministry’s manipulation of the map becomes more widely known, it will erode public trust.

The ministry appears to be rejecting science and carrying on with business as usual as it moves the lines around on the map and rejects what the panel told it to do, Britneff says.

“They chose to manipulate the data and to manipulate the public, which isn’t transparent, but is dishonest and untrustworthy.”

The panel’s work and the ministry’s alteration of it is playing out against not only a deepening ecological crisis but a steadily deteriorating situation for the province’s forest industry.

Throughout last year, numerous wood-processing facilities including some of the largest sawmills in the world, as well as pulp mills and wood pellet mills, closed their doors due to B.C.’s deepening “timber supply” crisis.

Employment in the industry has been roughly halved in 20 years with 40,000 jobs eliminated in the logging and milling sectors since just 2005, a result of the best and most accessible valley-bottom forests being logged away and companies having to travel extraordinary distances at extraordinary cost to find enough trees of sufficient quality to justify the expense.

In some cases, the haul distances have lengthened to the point they violate transportation health and safety rules, with logging truck drivers pulling up to 16-hour days moving logs from the remote northwest reaches of the province near Dease Lake to Houston, where the logs are offloaded from one truck before being loaded onto another for the final push to Prince George.

Because of the rapid escalation of logging in the interior of the province in particular, there is widespread recognition that logging rates, which have been falling for years, will fall further still. Virtually all of the trees currently logged come from primary forests. As those forests disappear, they’re being replaced with biologically impoverished tree plantations or artificial forests.

Those plantations now cover vast swaths of the landscape. But their trees are too small and too young to be logged by Canfor, West Fraser, Dunkley and Tolko, the four companies that dominate the sawmilling industry in B.C.’s Interior.

With the end of accessible, high-quality trees in sight in B.C., Canfor and West Fraser in particular have plowed hundreds of millions of dollars collectively into milling operations in the southeast United States, where tree plantations dominate the landscape and can be logged at a much younger age than in northern climes because their trees grow so much faster.

Barring further protection of remaining old-growth forests in B.C., the likelihood is that such forests will continue to be logged but at the ultimate expense of more mills closing as the last vestiges of primary forest wink out.

A recent estimate is that by 2035 only 47 sawmills will remain in the province, down from the 111 such facilities operating “at full tilt” in 2005.

Forest ecosystems at risk

Among the old-growth forests that appear most vulnerable should the government accept the ministry’s manoeuvres are:

The Goat River watershed. This is one of a dwindling number of intact watersheds in the heavily fragmented and globally rare interior temperate rainforest, where centuries-old trees rival in size those once found in abundance on B.C.’s coast. The watershed is home to “a very important and highly sensitive population” of bull trout, a fish species that has suffered precipitous declines throughout North America due to clearcut logging and other industrial disturbances.

The west Chilcotin region near Itcha Ilgachuz Park. The region’s remnant natural forests are critical habitat for the province’s largest but rapidly dwindling woodland caribou population, which numbered 2,800 animals in 2003 before a massive upswing in clearcut logging, which brought wolf populations in closer contact with the caribou and caused their numbers to plummet to between 385 and 508 animals in recent years. The massive decline in the herd’s populations is of great concern because caribou have been taken from the herd in years past to try to augment critically endangered caribou herds elsewhere in the province.

The north Babine region. Despite the logging deferrals recommended by the panel, the ministry allowed big-treed old-growth forests to be logged late last year and early this year in this region. Portions of the wood fibre taken from those forests then went to make wood pellets, as revealed in a recent report by the BBC. Recent video footage taken by Conservation North captured logging in those forests by Canfor. The ministry map suggests further deferrals recommended by the panel in the region will be rejected in favour of logging.

The Klanawa watershed. This area on the southwest coast of Vancouver Island is home to ancient cedar, hemlock and spruce trees. The Island’s increasingly rare old-growth forests represent some of the largest natural storehouses of carbon on the planet and remain critical to moderating water flows and protecting salmon habitat. Many salmon populations in nearby watersheds like the Sarita River have suffered population collapses after being heavily logged and now require major investment to rehabilitate.

North Vancouver Island. Western Forest Products holds Tree Farm Licence 6, a sprawling area of 217,000 hectares in size, which makes it larger than 268,000 football fields. TFLs, which are granted by the provincial government, give companies exclusive rights to log forests, although the land itself remains publicly owned. The panel recommended that the equivalent of 10,426 football fields of remaining old growth in the heavily logged TFL be spared logging. But the ministry deleted all the panel’s recommended deferrals. In many other TFLs, the ministry similarly rejected the panel’s recommendations.

Talk and log

In their April 2020 report “A New Future for Old Forests,” Gorley and Merkel noted that while some people they spoke with were optimistic that the government would follow through on its commitments to protect more old growth, many others were skeptical.

The skepticism was born out of experience. As Gorley and Merkel wrote, more than 30 years ago the provincial government had received another report on the future of old-growth forests.

Submitted to the government in 1992, the report called for big increases in the protection of imperilled old-growth ecosystems. But in the decade to follow, logging rates, particularly in the vast central interior of the province, skyrocketed.

“We frequently heard about examples where current and past governments were perceived as having not followed through on initiatives or recommendations,” Gorley and Merkel reported, noting how previous provincial governments had ignored not only the advice of the Old Growth Strategy of 1992 but subsequent reports including the 2012 Forest Practices Board report on old-growth management and the 2013 auditor general’s report on biodiversity.

Once again, the government has a report before it calling for substantial increases in the protection of old-growth forests, including the rarest of the rare big-treed forests. In the words of the scientists who wrote the report: “All the forest types recommended and mapped for deferral are rare, at risk and irreplaceable.”

Now the question is whether the government will choose to be guided by what the scientists it appointed are saying or by Ministry of Forests bureaucrats who appear to have a very different agenda.

* Story updated on March 8 at 9:24 a.m. to include that password-protected data on a the ministry website was taken down shortly after this story was published.

[Top photo: An old-growth forest on Nootka Island, before it was logged. Several more such forests on the island off Vancouver Island’s northwest coast could soon be logged, according to a map by BC’s Ministry of Forests. Photo courtesy of CCPA.]