Articles Menu

Nov. 24, 2020

The most important transportation innovation of our time is not a new technology or mobility service. It is a set of pricing reforms that can make our transportation system more efficient and equitable. Variable road tolls and parking fees, with higher prices at times and places where driving imposes greater costs, and a portion of revenues used to improve resource-efficient modes (walking, bicycling and public transit), can significantly reduce traffic and parking congestion, taxes and building costs, traffic crashes, pollution emissions, and sprawl, and help achieve social equity goals. In fact, many transportation problems are virtually unsolvable without pricing reforms. When motorists say "I oppose road tolls," they are saying "I support traffic congestion," because virtually no other solution really works.

Of all the common activities people engage in, none imposes more external costs than automobile travel. Every time somebody purchases a vehicle, they expect governments to provide roads and businesses to provide parking facilities for their use. These facilities are more expensive than most people realize, and somebody must bear these costs. The choice, therefore, is not between free or priced facilities, it is between paying directly, through user fees, or indirectly through hidden subsidies that raise our taxes and the prices of other goods; your home and a restaurant meal are cost more to pay for "free" off-street parking. Paying indirectly is unfair and inefficient because it forces people who drive less than average to subsidize the facility costs of their neighbors who drive more than average, and it increases total vehicle travel, resulting in more congestion, traffic casualties, pollution emissions and sprawl than would occur with more efficient pricing. Smarter transportation pricing can benefit everybody, including motorists who pay but save in other ways.

Compared with other modes, travel automobile travel creates far more congestion, crash risk, and noise and air pollution, while degrading walking and bicycling conditions and encouraging sprawled development; it is resource-intensive and imposes large external costs. As a result, a world in which driving is cheap is a world in which other important amenities—walking and bicycling, housing, safety and health, and environmental quality—are more expensive.

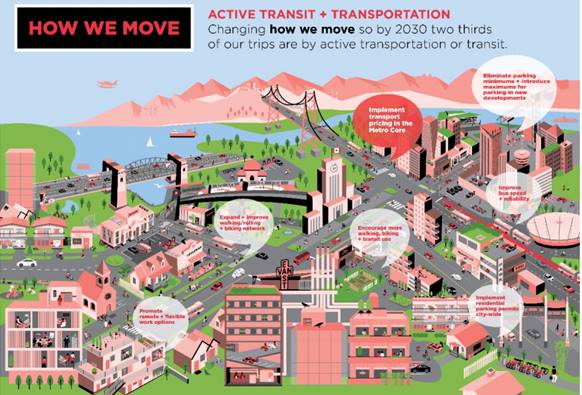

This issue is popping up all over. Last month I participated in a virtual workshop, "Managing Lanes for Transportation Efficiency & Fairness," which discussed how High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes can reduce traffic problems in Hillsborough County, Florida. This month, the city of Vancouver approved its Climate Emergency Action Plan (see illustration below). Although the plan includes many emission reduction policies, media attention focuses its proposal to toll a few urban highways. The plan is often described as good for the environment but harmful to lower-income families.

New York plans to implement congestion pricing (or, as I prefer to call it, decongestion pricing) next year. Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, and Toronto are just a few other North American urban regions that are considering efficient road tolls and parking pricing reforms. These plans tend to face significant criticism, much of it misplaced.

Road and parking pricing reforms can provide large, widely-dispersed benefits. However, we've done a poor job of communicating these benefits to the public. We've allowed the discussion to focus on costs while overlooking many benefits. Let’s see if we can mobilize a popular movement that advocates, "Raise our road tolls and parking fees, please!"

These pricing reforms reflect a paradigm shift that is changing the way we define transportation problems and evaluate potential solutions. The old paradigm assumed that "transportation" primarily means driving, so "transportation problem" refers to constraints on driving, and "transportation improvement" means that driving becomes faster, easier and cheaper. From this perspective, road and parking pricing seem harmful, since they reduce the amount that people can drive. The new paradigm is more multi-modal and comprehensive. It recognizes other modes and other community goals. The new paradigm inverts conventional planning objectives: instead of maximizing mobility it maximizes accessibility, which minimizes the amount of travel required to serve our needs. As a result, the new paradigm supports vehicle travel reduction targets, such as those established in California, Washington State, and Vancouver, with transportation demand management (TDM) incentives to achieve those targets. The new paradigm therefore supports transportation pricing reforms as a way to increase overall accessibility and transportation system efficiency.

However, these pricing reforms face considerable obstacles. There are a lot of misconceptions about them, and many of the people would could benefit most oppose them. They've been bamboozled into lobbying against their own self-interest. Let’s examine efficient transportation pricing, its potential benefits, and respond to common criticisms.

A basic economic principle is that markets are most efficient and fair if prices (what we pay for a good) reflect the full costs of producing that good. Automobile travel imposes many costs, some of which are fixed (users pay the same, regardless of how much they drive) or external (they are borne indirectly, regardless of whether they own a vehicle), and so are inefficiently priced. Transportation becomes more efficient if prices internalize currently external costs, and if fixed costs are converted into variable costs, so users pay in proportion to the costs they impose.

Motor Vehicle Costs

Internal Variable |

Internal Fixed |

External |

|

|

|

Conventional planning often considers on these costs individually. It identifies the road toll needed to internalize congestion costs, the parking fee required to optimize parking facility use, or the emission charge needed to internalize pollution costs. However, these impacts are cumulative and synergistic: roadway underpricing not only causes traffic congestion, it also increases parking costs, crashes and pollution emissions. Similarly, underpricing pollution increases traffic congestion, crashes and parking costs. Described differently, transportation pricing reforms can provide multiple economic, social and environmental benefits, they are "win-win" solutions.

Transportation pricing reforms can include:

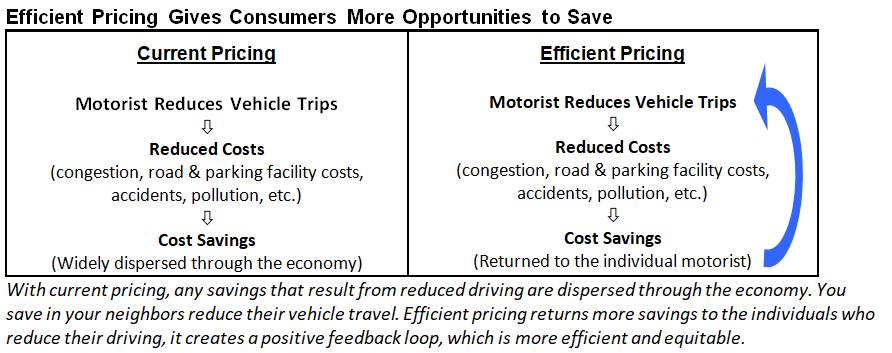

Although critics generally assume that efficient pricing harms consumers, it actually offers them a new opportunity to save money that does not currently exist. For example, if roads and parking facilities are financed indirectly, using general taxes or incorporated into building development costs, consumers pay regardless of how much they drive. With efficient pricing, consumers have a new opportunity to save money if they reduce the transportation costs they impose, for example, by reducing their peak-period vehicle trips, using less costly parking facilities, or shifting from driving to more resource-efficient modes.

Most people never purchase a road or parking space, so they have no idea how very expensive these facilities really are. They say, "I just want free roads and parking so I can drive to work," without realizing that this requires thousands of dollars a year in subsidies. Let me illustrate. According to data from the most recent, "Status of the Nation’s Highways, Bridges, and Transit: Conditions & Performance" report, it typically costs $11-44 million to add a lane-mile to an urban arterial, and $15-64 million dollars to add a lane-mile to a large-city freeway. Assuming 5% depreciation over 25 years, and that an urban highway lane accommodates 6,000 additional peak-period vehicles 300 days per year, urban roadway expansions cost $0.44-2.50 per additional vehicle-mile; this is the toll needed to recover project costs. In other words, expanding urban highways typically costs 20 to 100 times more than what motorists pay in fuel taxes when driving on that facility; the remaining highway costs are subsidized.

Similarly, a typical urban parking space costs $10,000-60,000 to construct, and including maintenance and operating costs has $1,000-4,000 annualized costs, requiring a $5-20 daily fee. Giving motorists a free parking space is equivalent to giving them stack of $100 bills each year. It is more efficient to charge users directly, or cash out parking, so travellers who don't drive receive the cash equivalent of the parking subsidies offered to motorists.

When faced with efficient prices, travelers will often choose alternative routes, modes or destinations. In other words, many travelers will drive is somebody else pays their costs, but not if they must pay themselves. Compared with unpriced-facilities, cost-recovery road or parking pricing typically reduces affected vehicle travel by 10-30%, indicating that a major portion of facility costs, traffic congestion, crash damages and pollution emissions result from underpricing underpricing. This additional travel is economically inefficient; it consists of vehicle-miles that travelers value less than its costs, and would willingly forego rather than pay directly.

There is a rich vocabulary for describing overpricing; if we think somebody charges us too much we say that we are cheated, gouged, gypped, fleeced, bilked, ripped off, conned or duped. There is no comparable vocabulary to describe underpricing, although it is equally inefficient and unfair since it results in wasteful consumption and external costs that those who underpay impose on other people.

Let me summarize various reasons to implement more efficient road and parking pricing.

Many people assume that roadway costs are paid by user fees, such as fuel taxes and tolls, but in fact, user fees only cover about half of all roadway expenditures. Although fuel taxes finance intercity highways, most local roads and traffic services are funded primarily by general taxes that residents pay regardless of how much they drive. Similarly, most parking costs are paid indirectly, incorporated into building rents and the costs of other goods.

Road tolls and parking fees are generally applied on particularly expensive facilities, such as major bridges, urban highways, and downtown parking facilities, where it would be unfair to force other people to subsidies those costs. Currently, U.S. fuel taxes average about 48₵ per gallon, or 2.5₵ per vehicle mile. In the United States, governments spend $223 billion and motorists drive 3,255 billion vehicle-miles, which averages about 6.8₵ per vehicle-mile. As previously described, accommodating an additional highway trip cost $0.50-1.00 per vehicle-mile, and an urban parking space costs $1,000-4,000 per year. It is unfair for people who seldom use those facilities to subsidize their costs. As a result, even if most roads and parking facilities are unpriced, it is efficient and fair to charge tolls on particularly costly facilities.

Many motorists are freeloaders, using expensive roads and parking facilities, and imposing congestion, crash and pollution costs, in jurisdictions where they don't reside and pay no taxes. You might assume that these costs are reciprocated: that each suburban commuter who drives to a central city is matched by a city commuter who drives to that suburb, but it doesn’t work out that way. A typical urban region has far more suburb-to-city than city-to-suburb commuters; city roads and parking facilities are far more costly; and city residents bear far more vehicle congestion, crash risk and pollution costs than suburbanites. These costs also tend to be regressive since in most regions, central city residents have lower average incomes than suburb-to-city automobile commuters. As a result, local governments have a fiduciary obligation to recover these costs through road tolls and parking fees.

Most transportation pricing reforms are part of an integrated package of policies to improve and encourage resource-efficient modes, and to help create more compact, multi-modal communities. For example, much of the toll revenues from London, Stockholm, and soon New York, are invested in public transit improvements, and decongestion pricing reduces bus delays, making the service faster and more efficient. Vancouver's Climate Action Plan includes dozens of other policies, besides road tolls, to help create a more affordable, accessible, inclusive and resource-efficient urban region. This includes substantial improvements in walking and bicycling conditions; large investments in public transit improvements, transit priority on 10 key corridors; more compact and mixed development to ensure that 90% of residents live within an easy walk or role of their daily needs; eliminating parking minimums in new developments; and encouraging remote and flexible work options.

These reforms can provide huge savings and benefits. Residents of compact, multi-modal neighborhoods tend to own fewer motor vehicles, drive less, spend significantly less on transportation, exercise more, are healthier, have greater economic mobility, and have more efficient public services, as well as producing far less pollution than they would in sprawled, automobile-dependent areas. Although Vancouver's Climate Action Plan is primarily intended to reduce emissions, it could also be described as an affordability, health or social equity plan.

Urban traffic congestion tends to maintain self-limiting equilibrium: it increases to the point that travelers forego some potential peak-period vehicle trips. If roads are expanded, that latent demand soon fills the additional capacity, resulting in more total travel, called induced demand, and little reduction in delay to other road users. High quality (relatively fast, frequent and integrated) public transit can reduce the point of congestion equilibrium, so congestion becomes less severe, but by itself cannot eliminate it. Only decongestion pricing, with higher tolls during peak periods and lower tolls off-peak, can cities significantly reduce traffic congestion.

With current pricing, travelers have little incentive to use resource-efficient modes, even if they are competitive in convenience. For example, a typical motorist spends about $10 per day in fixed vehicle ownership costs, but only about 15₵ per mile in variable operating costs. For a typical commuter, driving to work costs only about $2.50 for fuel and tire wear, far less than two bus fares, and there is even less incentive to use efficient modes for local errands. Efficient road and parking pricing gives travelers an incentive to use efficient modes when possible, for example, walking and bicycling for local errands, and public transit when traveling on major urban corridors. Over the long run, a combination of non-auto mode improvements and incentives to use those modes can have more structural effects: they create a critical mass of users so families and businesses choose more multi-modal locations, and use of those modes becomes socially acceptable.

Below are responses to common objections to efficient road tolls and parking fees.

Although a given toll or parking fee represents a larger portion of income for poor compared with wealthy households, in practice, physically and economically disadvantaged people seldom drive on tolled highways or park in areas with high parking fees; they tend commute by walking, bicycling or public transit, or work off-peak shifts when roads are uncongested. Decongestion tolls only apply to a small portion of total regional travel, peak-period vehicle trips on major bridges and highways, or entering city centers. Most of these corridors already have public transit services, and transit services can improve significantly if decongestion pricing reduces bus delays, increases demand, and provides more funding that leads to more service. As a result, in most cities, only a small number of lower-income people would actually pay decongestion tolls, while a large number could benefit significantly from tolls if a portion of the revenue is used to improve non-auto modes.

When people claim that transportation pricing is regressive, they are only considering primary impacts. It is important to consider all impacts. For example, without user fees, roads and parking facilities are subsidized with revenue sources that are often more regressive overall, such as sales and property taxes. Underpricing causes people to drive more, increasing traffic and parking congestion, pedestrian delays, traffic risk and pollution emissions, which tend to be particularly harmful to disadvantaged groups. Over the long term, efficient road and parking pricing, with a portion of revenues used to improve non-auto modes, tends to create a more multi-modal transportation system, where non-drivers have better mobility options and face less social stigma. The table below summarizes these impacts.

Analysis Scope

Impacts |

Pricing Reform Equity Effects |

|

Primary (Direct) Road tolls and parking fees. |

Regressive to low-income motorists. |

|

Secondary (Indirect) Subsidies required to finance facilities. Traffic congestion, pedestrian delays, crash risk, and pollution impacts. |

Lower-income people benefit from reduced taxes, rents and prices that would be required to subsidize roads and parking facilities. They also benefit a lot from reduced delay to buses, pedestrians and bicyclists; reduced crash risk; and reduced pollution emissions. |

|

Tertiary (Long Term) Land use development patterns and social expectations |

Lower-income travellers benefit from more multi-modal transportation planning, more affordable, compact development, and increased social status of non-auto travel. |

Of course, you could imagine a scenario in which a deserving, hard-working but economically disadvantaged traveler needs to drive on congested roads. Some road pricing systems address this by offering income-based discounts and exemptions. For example, L.A. Metro provides a one-time $25 transponder credit and waives the monthly maintenance fee for L.A. county residents who fall below an income threshold, and the London congestion charge includes a "Blue Badge" discount for drivers with disabilities, and refunds are provided to certain people traveling to hospital appointments.

Critics often assume that efficient transportation pricing harms automobile-dependent suburbanites. For example, Professor Andy Yan, director of Simon Fraser University's City Program warned that a congestion charge could become a "sizable burden" for some lower-income suburbanites, saying, "It's important to recognize how high prices in Vancouver have pushed low-income earners out of the downtown, forcing them into longer commutes. About 45 per cent of those working in the city live in the outer suburbs."

This is a huge miss-representation of the issue. It implies that a significant portion of suburbanites must drive to the central city, and it ignores the large benefits that efficient pricing can provide to motorists (less congestion) and transit users (more transit service, less bus delay). The proposed congestion charge would only apply on a few major bridges or highways during peak periods, so tolls would only be charged for a few percent of total regional trips. Those corridors have excellent transit services, including Skytrain and frequent buses. Travel surveys show that about half of all suburb-to-Vancouver trips are currently made by public transit, and this mode share can increase substantially with improved service and better incentives; that, after all, is the goal. Most moderate-income suburbanites already use public transit when travelling to Vancouver, and more will choose that option if service is improved, so for every one that will pay the toll, ten or more moderate-income suburbanites will benefit. We need more objective and comprehensive analysis that puts these impacts into perspective by accounting for all of the benefits and beneficiaries of a package of pricing reforms and improved travel options.

This reflects a type of "horizontal equity," which assumes that everybody should be treated equally. If most roads are unpriced, it seems unfair to price others. But the roads and parking facilities that are priced tend to be the most expensive: major bridges, urban highways, and parking facilities in areas with very high land values. Without pricing, people who use those facilities are being subsidized a lot by people who don’t: if these facilities are financed by fuel taxes, their use is cross-subsidized by motorists who seldom use them, and if they are financed by general taxes, their use is subsidized by local taxes paid by many people who seldom or never drive on those facilities.

Older pricing technologies were costly to operate and inconvenient to use. Toll booths are expensive to build, labor intensive and require drivers to stop, wasting time and fuel. Mechanical parking meters require users to have the proper change, and prepay for an amount of time that may turn out to be excessive or inadequate. However, newer electronic pricing technologies are more cost-effective, convenient and flexible, allowing users to pay automatically. Their costs can be minimized if one pricing system is used throughout a region.

Critics often cite extreme examples of road tolls and parking fees to generate fear. For example, a Virginia toll road automatically calculates prices based on traffic volumes, which very occasionally results in $40+ tolls. Although exceptional, these prices get a lot of media coverage, giving people the impression that road tolls make driving unaffordable to anybody who is not rich. These fears can be addressed by setting maximum prices, and offering discounts and exemptions to disadvantaged groups, such as lower rates for lower-income people, or refunds for motorists driving to hospitals.

It is also important to point out ways that efficient pricing benefits disadvantaged groups, by reducing they subsidies they would pay if roads are funded through general taxes and parking facility costs are incorporated into building rents; by improving mobility options; and over the long run by helping to create more multi-modal communities.

|

Efficient Pricing Benefits

|

Transportation pricing reforms are often described as "good for the environment but bad for the economy," based on the assumption that employees and customers need to drive to reach businesses. This reflects the old automobile-oriented planning paradigm. In fact, businesses can benefit overall from more efficient transportation pricing.

The large cities where road tolls and parking fees are being implemented are multi-modal; many commuters and customers arrive by non-auto modes. Reducing traffic congestion and improving non-auto modes improves access to businesses overall.

Cars don't have wallets; people have wallets, and since automobiles are expensive to own and operate, policies that reduce household expenditures on vehicles and fuel leave more money circulating in the local economy. For example, if transportation policy reforms convince a household to shed a car (own one rather than two vehicles), that household has $4,000-8,000 more to spend on other goods, including public transit, local food and drinks, and more housing, all of which tend to generate more regional jobs and business activity per dollar than vehicle and fuel expenditures. Described differently, a typical household living within the city probably spends about $50,000 on local goods (rent, food, clothing, etc.) which generates the employment, business profits and local tax revenue of 500-600 out-of-town customers spending $100 per trip.

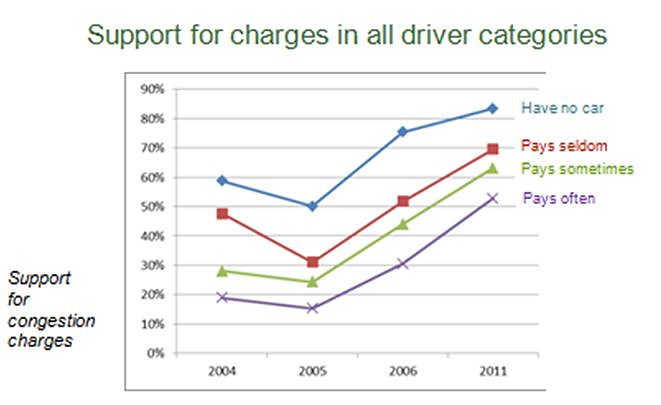

The best evidence that pricing reforms should be welcomed, not feared, is the experiences of cities that have tried them. For example, in 2006 Stockholm, Sweden, began charging vehicles entering the inner city area on weekdays between 6:30 a.m. and 6:30 p.m. 10 to 20 kronor (US$1.27 to US$2.54) per trip, with a maximum daily charge of 60 kronor (US$8.00). After a seven-month pilot, Stockholm residents voted in favor of making the system permanent. Public support increased in subsequent years, including by the motorists who pay the fee, as they experienced the benefits, illustrated in the following graph.

Although initially considered "political suicide," the program is now considered successful overall by experts, media, and the general public. It reduced traffic volumes by about 25% and increasing public transit ridership by 40,000 users per day. About 350,000 vehicles per day pay the fee, generating between 3,500,000 and 21,000,000 kronor (U.S. $500,000 to $2.7 million) in daily revenue. Retail sales in central Stockholm shops increased compared with previous years, including significant increases in grocery sales in central neighborhoods, which probably reflects increased purchases by area residents who are more likely to shop locally rather than drive to shop.

To address parking problems in downtown Pasadena the city proposed pricing on-street parking as a way to increase turnover and make parking available to customers. Many local merchants originally opposed the idea. As a compromise, city officials agreed to dedicate all revenues to public improvements that make the downtown more attractive. This connected parking revenues directly to added public services. With this proviso, the merchants agreed to the proposal. This created a "virtuous cycle" in which parking revenue funded community improvements that attracted more visitors which increased the parking revenue, allowing further improvements. This resulted in extensive redevelopment of buildings, new businesses and residential development. Parking is no longer a problem for customers, who can almost always find a convenient space. Local sales tax revenues have increased far faster than in other shopping districts with lower parking rates, and nearby malls that offer free customer parking. This indicates that charging market rate parking (i.e., prices that result in 85-90% peak-period utilization rates) with revenues dedicated to local improvements can be an effective ways to support urban redevelopment.

Why are motorist such cheapskates? Owners of expensive cars often complain about paying their fair share of the roads and parking facilities needed to drive their vehicles. They expect other people to subsidize their vehicle travel. It's time to rethink transportation pricing.

Many people find it difficult to image that they could benefit from higher prices. We have been indoctrinated to consider ourselves "consumers," which assumes that our world becomes better if we have more stuff, in this case, more vehicle miles. From this perspective, there is nothing wrong with demanding free road and parking. However, those facilities are never really free, we bear their costs indirectly through higher taxes, rents and prices for other goods; face greater congestion, crash and pollution problems; and have fewer travel options and more sprawled development patterns.

Described differently, although we may sometimes be greedy motorists, we are also tax payers, community members, pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit passengers, all perspectives that benefit from transportation pricing pricing reforms. When all impacts are considered, everybody benefits from financial incentives that encourage travelers to use the most efficient mode for each trip: walking and bicycling for local errands, public transit when traveling on busy urban corridors, and automobiles when they are really the best option, considering all impacts.

Our challenge, as planners or advocates, is to better communicate the full benefits of efficient road and parking pricing. Pricing should be implemented as an integrated package with improvements to resource-efficient modes, so travelers have better alternatives to driving. If appropriate, incorporate maximum price limits, discounts and exemptions for people who truly must drive during peak periods. Point out that, without efficient pricing, other people are forces to subsidize roads and parking facilities that they don't need, and downstream traffic problems increase.

Stuart Cohen and Alan Hoffman (2019), Pricing Roads, Advancing Equity, TransForm.

Joe Cortright (2017), Transportation Equity: Why Peak Period Road Pricing is Fair, City Observatory.

Brianne Eby, Martha Roskowski and Robert Puentes (2020), Congestion Pricing in the United States: Principles for Developing a Viable Program to Advance Sustainability and Equity Goals, Eno Center for Transportation.

EcoNorthwest (2019), Fair and Efficient Congestion Pricing for Downtown Seattle, Uber Technologies.

ITF (2018), The Social Impacts of Road Pricing Summary and Conclusions, International Transport Forum.

Benjamin Krohnengold (2020), “Keeping the Streets Clear: Advancing Transportation Equity by Limiting Exemptions under New York City's Central Business District Tolling Program,” Fordham Urban Law Journal, Vol. 47.

Marc Lee (2018), Getting Around Metro Vancouver: A closer look at mobility pricing and fairness, Candian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Todd Litman (2020), Raise My Taxes, Please! Evaluating Household Savings From High Quality Public Transit Service, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2019), Socially Optimal Transport Prices and Markets, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Michael Manville (2017), Is Congestion Pricing Fair to the Poor?, 100 Hours.

Michael Manville and Emily Goldman (2018), “Would Congestion Pricing Harm the Poor? Do Free Roads Help the Poor?” Journal of Planning Education and Research, Vo. 38, issue 3, pp. 329-344.

Metro Vancouver (2018), Metro Vancouver Mobility Pricing Study: Full Report on the Findings and Recommendations for an Effective, Farsighted, and Fair Mobility Pricing Policy, Translink.

PDOT (2020), Pricing Options for Equitable Mobility (POEM), Portland Department of Transportation.

SCAG (2017), Decongestion Fee System, 100 Hours Program, Southern California Association of Governments.

Bruce Schaller (2018), Making Congestion Pricing Work, Schaller Consulting.

Susan Shaheen, Adam Stocker and Ruth Meza (2020), Social Equity Impacts of Congestion Management Strategies, Transportation Sustainability Research Center.

Lisa Schweitzer and Brian Taylor (2008), “Just Pricing: The Distributional Effects of Congestion Pricing and Sales Taxes,” Transportation, Vol. 35, No. 6, pp. 797–812.

SPUR (2020), Value Driven: How Pricing Can Encourage Alternatives to Driving Alone and Limit the Costs that Driving Imposes on Others, San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association.

Lindsay Wiginton (2018), Fare Pricing: Exploring how Road Pricing on the DVP and Gardiner Would Impact Income Groups in the GTHA, Pembina Institute.