Articles Menu

[Supreme Court of BC Justice Affleck rejected the very compelling 'defence of necessity' raised by climate defenders arrested at the TransMountain Pipelines terminal in Burnaby, BC. The trial will begin on March 11, and an appeal of this ruling seems likely.]

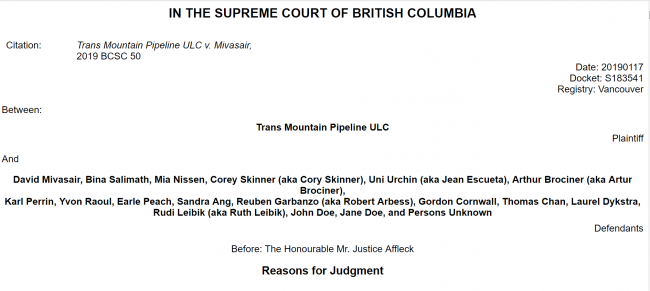

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

|

Citation: |

Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC v. Mivasair, |

|

|

2019 BCSC 50 |

Date: 20190117

Docket: S183541

Registry: Vancouver

Between:

Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC

Plaintiff

And

David Mivasair, Bina Salimath, Mia Nissen, Corey Skinner (aka Cory Skinner), Uni Urchin (aka Jean Escueta), Arthur Brociner (aka Artur Brociner),

Karl Perrin, Yvon Raoul, Earle Peach, Sandra Ang, Reuben Garbanzo (aka Robert Arbess), Gordon Cornwall, Thomas Chan, Laurel Dykstra,

Rudi Leibik (aka Ruth Leibik), John Doe, Jane Doe, and Persons Unknown

Defendants

Before: The Honourable Mr. Justice Affleck

Reasons for Judgment

|

Counsel for the Provincial Crown: |

M .Ruttan |

|

Counsel for the Defendant, David Gooderham and Jennifer Nathan: |

M. Peters |

|

Place and Date of Trial/Hearing: |

Vancouver, B.C. December 3 and 4, 2018 |

|

Place and Date of Judgment: |

Vancouver, B.C. January 17, 2019 |

[1] Two alleged contemnors apply for what they term “leave” to raise the defence of “necessity” and to lead evidence on an issue arising out of s. 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (U.K.), 1982, c. 11 (the “Charter”). Their applications are described more fully in para. 10 below.

[2] I was invited by all counsel to conduct what is commonly referred to as a Vukelich hearing.

[3] In R. v. Cody, 2017 SCC 31 at para. 38, there is the following:

[38] … trial judges should use their case management powers to minimize delay. For example, before permitting an application to proceed, a trial judge should consider whether it has a reasonable prospect of success. This may entail asking defence counsel to summarize the evidence it anticipates eliciting in the voir dire and, where that summary reveals no basis upon which the application could succeed, dismissing the application summarily (R. v. Kutynec (1992), 7 O.R. (3d) 277 (C.A.), at pp. 287-89; R. v. Vukelich (1996), 108 C.C.C. (3d) 193 (B.C.C.A.)).

[4] On December 4, 2018, following the Vukelich hearing I summarily dismissed applications by David Gooderham and Jennifer Nathan with written reasons for judgment to follow. These are my reasons.

[5] Jennifer Nathan and David Gooderham are each charged with committing the common law offence of criminal contempt of court for their public disobedience of an injunction.

[6] On March 15, 2018, on the application of the plaintiff, an injunction was granted, which restrained the named defendants and other persons with notice of the injunction from physically obstructing, impeding or otherwise preventing access by the plaintiff, its contractors, employees or agents, to, or work in, any sites or work areas of the plaintiff, including what is referred to in the injunction as the Burnaby Terminal and the West Ridge Marine Terminal. At those sites, preparatory work was being done to enlarge a pipeline to transport petroleum from Alberta.

[7] On March 24, 2018, Jennifer Nathan was arrested for blocking access to the Burnaby Terminal. Ms. Nathan admits she was among a group of about 60 people who stood in front of the entry gate to the Burnaby Terminal. Ms. Nathan intended to disobey the injunction on that day in the presence of many other people in order to draw attention to her opposition to the proposed construction of the pipeline.

[8] On June 1, 2018, the injunction was varied but continued to restrain the defendants and other persons with notice of the injunction from physically obstructing, impeding or otherwise preventing access by the plaintiff, its contractors, employees or agents, to, or work in, any sites or work areas of the plaintiff, including the Burnaby Terminal and the West Ridge Marine Terminal.

[9] On August 20, 2018, David Gooderham was arrested for blocking access to the Westridge Marine Terminal. Mr. Gooderham admits he was among a group of five people who sat in chairs blocking access to the terminal. Mr. Gooderham’s intention in disobeying the injunction was also to draw attention to his opposition to the proposed pipeline. Both Ms. Nathan and Mr. Gooderham were aware that the construction of the pipeline was lawful at the time of their arrests. It had been authorized by a Federal Order in Council (“OIC”).

[10] On December 3, 2018, the trial of Ms. Nathan and Mr. Gooderham for criminal contempt of court began. The case for the Crown was presented through written admissions of facts. Prior to the beginning of their trial, Ms. Nathan and Mr. Gooderham (who I will refer to as “the applicants”) had filed a notice of application. Part 1 of the notice of application reads as follows:

1. In light of this Court’s ruling in Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC v. David Mivisair, 2018 BCSC 874 relevant to Thomas Sandborn on May 10, 2018 and your Lordship’s further ruling in the case as against Mr. Charles Coleman on June 13, 2018, wherein your Lordship held that you would not consider any other defences of necessity, the Applicants seek the following orders:

a. Leave of this Honourable Court to raise the defence of necessity as part of the Applicant’s defence to their charges of criminal contempt the Order of this Honourable Court of June 1, 2018, and in particular:

i. To call evidence concerning the growth of oil sands production in Canada to 2030 and the projected increase of CO2 and other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions accompanying that growth; the significance of the Trans Mountain Expansion project in facilitating that growth; and related evidence about whether the resulting increase in oil sands emissions is consistent with Canada meeting its 2030 reduction target;

ii. Evidence concerning whether Canada’s projected expansion of oil sands production to 2030 and 2040 is consistent with keeping global average surface warming below the 2°C threshold;

iii. Evidence concerning the Trans Mountain Expansion approval process, including the (i) National Energy Board (NEB) inquiry report May 19, 2016 recommending approval of the project, (ii) the Trans Mountain upstream emissions assessment report dated November 25, 2016, and (iii) the Ministerial Panel report November 1, 2016, showing that prior to the Order in Council authorizing the project of November 29, 2016, no public inquiry process addressed or answered questions about whether the growth of oil sands emissions to 2030 can be consistent with meeting Canada’s commitments under the Paris Agreement or whether the projected expansion of oil sands production to 2040 is consistent with keeping warming well below the 2°C threshold;

iv. Evidence concerning the current level and projected increase of global GHG emissions to 2030, the rising atmospheric carbon concentration level and the relationship between that increase and warming, the current rate of warming, and the impacts of warming and related changes in the earth’s climate system, the severity of the impacts that have already occurred and are occurring, and the projected impacts to 2030 and after;

b. A declaration that the Applicants, along with all Canadians, have a fundamental right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life; the state action of the Canadian Government to expand the Trans Mountain Pipeline imperils the Applicants’ and all citizens’ right to Life, Liberty and Security as protected by section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, being Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, enacted by the Canada Act, 1982 (U.K.) c. 11 (hereinafter the “Charter”);

c. A remedy pursuant to section 24(1) of the Charter staying the prosecution of the Applicants as a breach of process;

d. Such further and other order or orders as counsel may request and this Honourable Court deem just.

[11] If the defence of necessity was held to have an air of reality, the applicants intended to offer a substantial body of evidence to demonstrate the following:

2. Oil sands production in Canada is projected to expand from 2.5 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2015 to 4.236 million bpd by 2030.

3. On November 29, 2016, the Government of Canada approved the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. The project will increase the shipping capacity of an existing pipeline from 300,000 bpd to 890,000 bpd, adding 590,000 bpd of new shipping capacity (about 25% of the projected expansion of oil sands production between 2015 and 2040).

4. If Canada continues to expand oil sands production as currently projected, the annual level of greenhouse gas emissions in that industry will be about 44 million tonnes (Mt) higher by 2030 than in 2015.

5. Technological innovation in the oil sands production process will not reduce carbon intensity per barrel sufficiently to offset the currently projected 44 Mt increase in the annual level of oil sands emissions to 2030, above the 2015 level. While Alberta has legislated a “cap” that purports to limit the growth of oil sands emissions to an annual upper limit of 100 Mt, the cap does not cover all of the emissions associated with the expansion of the industry. The cap will do nothing to curb the 44 Mt increase in oil sands emissions that is expected to occur between 2015 and 2030, if production expands as currently projected.

6. The oil and gas sector, including oil sands, is Canada’s largest emitting sector, comprising about 26% of the total.

7. In December 2015, Canada became a signatory to the Paris Agreement. Canada agreed to reduce the level of its total annual emissions by 30% below the 2005 level by 2030. The 2005 level was 732 Mt. The commitment is 517 Mt.

8. Canada’s total annual emissions are currently projected to increase to 728 Mt by 2020. To meet its target, Canada’s annual emissions level would have to be cut by 211 Mt during the next decade.

Global emissions, atmospheric carbon, and warming

9. Global mean surface temperature for the decade 2006-2015 was 1.0°C higher than the average between the 1850-1900 period. The dominant cause of the observed warming is emissions caused by fossil fuel burning. Estimated global warming caused by human activity is now increasing at 0.2°C per decade. [IPCC October 7, 2018, SPM A.1; IPCC, 2013, The Physical Science Basis, D.3]

10. More than two thirds of the total surface warming has occurred since 1970.

11. The total annual level of emissions released into the atmosphere globally includes both carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning as well as other greenhouse gases (methane, nitrous oxide and others) and also emissions from human activities relating to land use, deforestation, and land use change. In 2016, the annual level of all global emissions is estimated to have reached 53.4 billion tonnes (Gt) of C02eq. The share of the total emissions in 2016 from burning fossil fuels is estimated to have been 36.2 GtC02, almost 70% of the annual total. The annual level is still increasing.

12. In December 2015, under the terms of the Paris Agreement, Canada and other countries agreed to reduce their emissions. The magnitude of each country’s commitment is voluntary. There is no mechanism to impose larger commitments, or to enforce compliance.

13. Under the terms of the Paris Agreement, Canada and 195 other countries also committed to “holding the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C.” Those thresholds reflect the conclusion of the scientific evidence that warming exceeding 1.5°C will have grave impacts on human settlements, livelihoods and on biodiversity and ecosystems, and that the risks of more destructive outcomes markedly increase as warming approaches or exceeds 2°C.

14. A carbon concentration level of 450 parts per million (ppm) correlates with a rise in global surface temperature of 2°C.

15. The conclusion of the scientific evidence is that the rising atmospheric carbon concentration shows a linear relationship with the observed warming of global surface temperature. The carbon concentration level reached an annual average of 405 ppm in 2017, a rise of 2.3 ppm above the previous year. Sixty years ago, it was 315 ppm. The rise in global CO2 concentration since 2000 is about 20 ppm per decade.

Mitigation and the global emissions gap

16. The UN report concludes that by 2030 global GHG emissions from all human-induced sources must not exceed 41.8 GtC02eq, if the 2°C target is to be attained with higher than a 66% chance of success.

17. The UN report concludes that even assuming all of the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) made by signatories to the Paris Agreement are fully implemented and achieved over the next decade (including Canada’s promised 30% reduction, which represents approximately 0.215 GtC02eq), total global emissions (51.9 GtCO2eq in 2016) are projected to rise to 55.2 GtCO2eq by 2030.

18. Implementation of all the NDCs will not be enough to offset the growth of emissions in other countries which are projected to substantially increase over the next decade and to achieve the deep cuts required to meet the 41.8 GtCO2eq target.

19. In order to meet the 2030 reduction target (to allow a 66% chance to keep future warming of global average surface temperature within the 2°C threshold), the world’s leading economies would have to find an additional 13.5 GtCO2eq of reductions.

20. The existing NDCs (including Canada’s pledge) represent only one-third of the total reductions needed to meet the 2°C reduction target.

21. Oil accounts for 34% of global CO2 emissions, comprising 12.5 billion tonnes of the total 36.2 billion tonnes (GtCO2) released into the atmosphere in 2016.

22. The scientific evidence concludes that if the world is going to keep warming to less than 2°C, global oil consumption must start to decline by 2020. One study, the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 450 Scenario, has concluded that global oil consumption will have to decline from 90.6 million bpd in 2014 to 74.1 million bpd by 2040.

23. The UN report, published November 3, 2017, concludes that full implementation of all existing conditional and unconditional NDCs by 2030 and comparable action after 2030 is consistent with a temperature increase of about 3.2°C by 2100 relative to pre-industrial levels. The report further concludes that if the emissions gap is not closed by 2030, it is extremely unlikely that the goal of keeping warming to well below 2°C can still be reached.

Impacts

24. The impacts to human and ecological systems caused by warming and related change in the earth’s climate system are already far advanced, and have accelerated during the past two decades.

25. Warming in the Arctic regions is already 3°C above the preindustrial level, rising an average 1°C per decade since 1990. The result has been melting of permafrost and loss of Arctic sea ice, loss of the historical extent of snow cover, and loss of the earth’s albedo, which is the capacity of the earth’s surface to reflect solar energy back into the atmosphere. More than two-thirds of surface warming has occurred since 1970. Warming has already increased inland continental average surface temperatures in the range of 1.5°C, for example in Canada’s boreal forests and in South Asia. Observed changes include increased frequency and intensity of heat waves.

26. Between 1901 and 2010, sea level rose by 19 cm (71/2 inches). The average rise over that period was 1.7 mm per year. The rate has accelerated, rising by an average 3.2 mm per year between 1993 and 2010. The impacts in some coastal regions are already acute in densely populated low-lying agricultural river deltas, in particular the Mekong, in Bangladesh, and the Nile delta, where salinification is degrading and destroying the productivity of agricultural land and flooding is displacing settled populations. About 38% of the observed sea level rise is attributed to thermal expansion of the warming ocean. The balance of the increase in sea level comes from melting ice on land, namely glaciers in the world’s mountain ranges, as well as melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.

27. Loss of glacier area and mass has already occurred worldwide and is far advanced in some regions. The rate of loss is accelerating. Glacier loss is measured in gigatonnes (Gt) of ice loss. A single gigatonne is equal to one cubic kilometre of freshwater. For the period 2005-2009, the IPCC estimate glacier loss is a range of 166-436 Gt per year. There are 170,000 to 200,000 glaciers on the earth’s surface. In the Hindu Kush Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau, the majority of glaciers are receding. Over half of the world’s population lives in watersheds of major rivers that originate in mountains with glaciers and snow. The Indus, the core water system of Pakistan, is fed in part by glacial melt from the Himalayas. After these sources of glacial melt-water disappear, or when they are greatly reduced, the flow-rate of these rivers will then be limited by the pattern of local precipitation (seasonal rain and in some places seasonal snow at high altitudes). The rivers will then provide little or no runoff during the dry season, especially in arid or semi-arid regions. Assuming global average temperature increase is limited to 1.5°C, about one third of present-day ice mass of glaciers in the high mountains of Asia will be lost by the end of this century. About two thirds will be lost by 2071-2100 if no further effort is made to curb emissions.

28. The recently released IPCC Special Report on Global Warming to 1.5°C provides a comprehensive picture of the substantial differences in the outcomes for human and natural systems as warming increases from the current level of 1.0°C to 1.5°C, and the worsening adverse impacts to 2°C. The failure to implement unprecedented measures now to halt the continued growth of global GHG emissions will have marked and significant consequences as warming move above 1.5°C and approaches 2°C. In the case of threatened ecosystems (which support human livelihoods) the risks as we move above 1.5°C are characterized as “high” and become “very high” closer to 2°C. Above 1.5°C, and even as we approach that level, the risk of extreme weather events is characterized as “high”. Above 1.0°C all coral reefs are at “high risk” (as they now are), and at 1.5°C virtually all coral reefs will be gone by 2100.

The National Energy Board (NEB)

28. The NEB was charged with conducting the environmental review of the Trans Mountain project. The review commenced in early 2014 and concluded when the NEB released its report on May 19, 2016, recommending that the project be approved.

29. On December 19, 2013, the NEB released a report recommending that the Northern Gateway project be approved. During the Northern Gateway inquiry, the NEB had refused to admit or consider evidence relating to the GHG emissions associated with the expected increase of bitumen production facilitated by that project, and refused to admit scientific evidence about the impact of increased emissions and climate change.

30. On December 18, 2013, the City of Vancouver voted unanimously to intervene in the NEB hearing for the Trans Mountain Project, pursuant to a Council motion stating that one of the specific purposes of the intervention by the City was to seek a ruling that the pipeline inquiry should include an assessment of the emissions implications of the project, including the climate impact of the expansion of oil sands production facilitated by the project.

31. At that time, the rules governing the NEB process barred any right of Canadian citizens, or groups of citizens, to participate in the Trans Mountain inquiry with the right to call evidence and question the merits of the proponent’s project unless they could establish that they were directly affected by the project.

32. Accordingly, the proposed intervention by the City of Vancouver offered a lawful avenue for residents of Vancouver to put forward their concerns that the NEB address the emissions and climate issues, and to do that in a reasoned and informed way by calling evidence on those issues. A large number of Vancouver residents attended the City Council meeting and spoke publicly in the Council Chamber in support of the motion to intervene.

33. On April 2, 2014, when it issued the Hearing Order for the Trans Mountain Project which included the List of Issues, the NEB excluded from the List of Issues the environmental impacts associated with the upstream activities and development of the oil sands, including greenhouse gas emissions. The City of Vancouver applied for an order expanding the List to include those issues.

34. In a ruling on July 23, 2014, the NEB rejected an application by the City of Vancouver to expand the List of Issues, which would have permitted the City and other intervenors to call expert evidence about emissions and climate change. On October 24, 2014, the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed an application by the City of Vancouver for leave to appeal that ruling. On October 11, 2014, following an appeal from a substantially identical ruling concerning a different pipeline project designed to transport bitumen, the Federal Court of Appeal upheld the ruling by the NEB that excluded all evidence relating to climate change and emissions.

35. At that time, public discussion, including intervention by many of Canada’s leading energy economists and climate scientists, publicly challenged the prudence of excluding consideration of emissions and climate science from the NEB approval process. On May 26, 2014, three leading scientists from U.B.C. and S.F.U. published an open letter, co-signed by 300 scientists from universities across Canada, with leading American climate scientists, expressing grave concern that the panel in the Northern Gateway case did not look at the increase in global greenhouse gas emissions that would result from the projected expansion of oil sands production.

36. On June 10, 2014, 110 senior scientists and researchers from across North America signed a public statement calling for a moratorium on proceeding with any new infrastructure projects, including pipelines, explaining that the continued expansion of oil sands production would be inconsistent with Canada’s commitments to reduce CO2 emissions. Seven of the signatories, including a leading energy economist and climate scientists knowledgeable about the pace and impact of rising global GHG emissions, published an article on June 24, 2014, in the journal Nature, warning that the existing approval process failed to look at the cumulative impact of resource development projects.

37. However, when the House of Commons on June 19, 2014, debated the Government of Canada’s formal approval of the Northern Gateway pipeline, speakers for both of the two main opposition parties opposed the project for various stated reasons but not a single question was raised in the House about the fact that the NEB inquiry had refused to consider evidence about the emissions implications of the project. The subject of emissions and climate change was not mentioned in Parliament.

38. Through the summer and fall of 2015, leading up to the October 19, 2016 Federal election, I participated as a volunteer in door-to-door canvassing in the new created Granville constituency in the City of Vancouver in an attempt to encourage electors to consider climate policy and the position of candidates with respect to reform of the NEB pipeline inquiry process to ensure it would address the emissions implications of proposed pipeline projects.

39. Following the Federal election held in October 2015, the Government of Canada announced on January 27, 2016, what it described as “interim measures for Pipeline Reviews”. The new government declared that the ongoing NEB inquiries into the Trans Mountain, Line 3, and Energy East pipeline projects would continue unchanged. In the case of the Trans Mountain expansion, the creation of a new process was announced that would “assess the upstream greenhouse gas emissions associated with this project and make this information public”.

40. On March 19, 2016, the Government of Canada published a notice containing details of the new emissions assessment procedure. The notice stated that the assessment would include “a discussion of the project’s potential impact on Canadian and global emissions”. The new process was officially called the Review of Related Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimates for the Trans Mountain Expansion project (hereinafter the “upstream emissions review”).

41. However, the methodology governing the emissions assessment set out in the March 18, 2016 notice did not require that the review assess the potential impact of the expected expansion of oil sands production to 2040 on Canadian and global emissions. The upstream emissions assessment was not mandated to determine whether the projected growth of oil sands production, which would provide the economic rationale for the proposed pipeline project, could be consistent with Canada’s emissions reduction commitments.

42. When the NEB issued its report on May 19, 2016, recommending approval of the Trans Mountain Project, the document did not consider the emissions implications of expanding oil sands production and excluded any discussion of the impact of emissions on the climate system.

Upstream emissions review

43. The draft report for the upstream emissions review was also released on May 19, 2016, two months after the public notice describing the process and methodology.

44. The draft document reported that the oil sands production would increase from the 2014 level of 2.4 million bpd to 4.8 million bpd by 2040 - a doubling of production over the next twenty-five years. That projected growth was lowered to 4.3 million bpd in the final report released on November 25, 2016. The draft report found that the volume of new production accounted for by the expanded capacity of the Trans Mountain pipeline would add 13.5 to 17 Mt of new emissions to Canada’s annual total, lowered to 13 Mt to 15 Mt in the final report (which would represent a 20% increase in total oil sands emissions above annual level in 2016.)

45. The March 19, 2016 draft upstream emissions report did not consider, and did not answer whether that proposed expansion of oil sands production, and the oil sands emissions growth associated with the Trans Mountain project, was consistent with Canada’s commitment under the Paris Agreement. The report did not address the impact of the pipeline project on Canada’s cumulative emissions.

46. The draft report also failed to answer whether the proposed expansion of oil sands production to 2040 was consistent with Canada’s commitment to holding the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C. The draft report concluded that it was “unclear” whether the projected growth of oil sands production could be economically viable in a world that was committed to keep warming below 2°C.

47. The upstream emissions review was not a public inquiry. There was no public or media access. There was no record of its deliberations, or of the identity of the persons who wrote the documents, or with whom they discussed the evidence and their findings. There was no opportunity for citizens, or groups of citizens, to call evidence or to cross-examine or otherwise question the information adopted by the report. The notice published March 19, 2016, stipulated that “only publicly available data provided by the proponent (the owner of the pipeline) will be used”. Because it was not a juridical process, there was no opportunity for a citizen, or a group of citizens, to challenge the findings of the draft report, or challenge the methodology.

48. After the draft report was published on May 19, 2016, citizens were permitted to send written comments about the report by email to the office of Environment and Climate Change Canada.

49. The final version of the upstream emissions report was released publicly on November 25, 2016. The only significant change from the draft report was that the increased in Canada’s annual emissions attributed to the project was slightly reduced, to a range of 13 Mt to 15 Mt, and the projected growth of oil sands production to 2040 was lowered to 4.3 million bpd, instead of 4.8 million bpd given in the draft report.

50. The upstream emissions assessment report did not answer either of the key questions that are essential to determining whether the projected expansion of oil sands production to 2030 and 2040, which provides the economic rationale for the Trans Mountain project, can be consistent with Canada’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.

The Ministerial Panel

51. The Ministerial Panel on the Trans Mountain Pipeline was appointed in May 2016. The Panel’s mandate was to listen to members of the public at a series of public meeting in Alberta and British Columbia, at which citizens could attend and express their support for the project, or express concerns about what issues and evidence had been overlooked or inadequately dealt with during previous processes. The Ministerial Panel had no powers to make findings or draw conclusions based on evidence. The Panel had no power to make recommendations to the government.

52. The Panel conducted a number of public meetings in British Columbia, including a meeting in Vancouver on August 17, 2016. The Panel’s report was delivered to the government and was publicly released on November 1, 2016.

53. In its report, the Panel acknowledged that its role was not to propose solutions, but to identify important questions that remain unanswered. The Panel stated this question: “Can construction of the Trans Mountain Pipeline be reconciled with Canada’s climate change commitment?” (Ministerial Panel Report, November 1, 2016, page 46). The Panel described this as a “high-level question” and concluded that it “remains unanswered’’.

Political activity to avoid the peril

54. During the past six years, the applicant, Gooderham, has exhaustively pursued avenues of political activity to encourage, persuade, and induce the Government of Canada to reconsider its plans to approve new pipeline capacity that will facilitate substantial expansion oil sands production to 2040, because of his grave concern about the emissions implications of the proposed expansion.

55. To that end, starting in 2013 and through to November 2016 and after, he has made written and oral submissions to public bodies and to Members of Parliament and others, calling on the Federal government to conduct an independent and public inquiry to assess whether the projected increase in oil sands emissions to 2030 is compatible with Canada’s commitment to reduce its total GHG emissions, and to determine whether the projected growth of oil sands production to 2040 is consistent with Canada’s commitment to keep the increase of average global surface warming to less than 2°C, as Canada agreed to do under the Cancun Agreements in December 2010 and under the Paris Agreement of December 2015.

56. Gooderham, together with other citizens, made an oral submission to Vancouver City Council on December 18, 2013, urging elected Councillors to support a motion authorizing the City of Vancouver to intervene in the pending NEB inquiry for the Trans Mountain expansion project with the express purpose that the City would apply as an intervenor to ensure that the NEB inquiry would consider the upstream emissions associated with the planned expansion, the impact of that expansion on Canada’s cumulative emissions, and related issues based on climate science.

57. The NEB inquiry rejected the City of Vancouver’s application to include upstream emissions and climate in the List of Issues.

58. After examining the draft upstream emissions assessment report for the Trans Mountain expansion released May 19, 2016, Gooderham filed a detailed written submission with Environment Canada on June 20, 2016. The submission pointed out that the draft report had failed to answer core questions about whether the projected expansion of oil sands emissions facilitated by the proposed pipeline could be reconciled with Canada’s emissions reduction commitments for 2030, and also that the report had failed to determine if the planned expansion of oil production to 2040 was consistent with Canada’s commitment to keep warming well below 2°C.

59. On August 17, 2016, Gooderham made an oral submission to a public meeting in Vancouver held by the Ministerial Panel, and delivered to the Panel a written report containing an analysis of the emissions implications of the proposed expansion of Alberta’s oil sands production, the impacts of projected oil sands emissions growth to 2030 on Canada’s chances of meeting its emissions reduction target under the Paris Agreement, and an analysis of the draft upstream emissions assessment report demonstrating that the May 19, 2016 document had failed to answer whether the Trans Mountain project was consistent with Canada’s emissions reduction commitments.

60. Through September and October 2016, Gooderham wrote individually to elected Members of Parliament in the Vancouver region, forwarding to them his written analysis of the Trans Mountain upstream emissions assessment, and urging them to reconsider the proposed pipeline project, in view of the very serious emissions implications of the project, and the fatal omissions of the upstream emissions report to provide answers to the important questions.

61. Through September and October 2016, Gooderham raised his concerns about the adequacy of the emissions review process directly with his own Member of Parliament by letter, and at a public meeting on September 7, 2016.

62. On November 1, 2016, the Ministerial Panel’s report was publicly released. The Panel’s report quoted substantial portions of Gooderham’s August 17, 2016 submission, and affirmed that the question “remains unanswered” whether the project could be reconciled with Canada’s climate change commitments.

63. The Trans Mountain Project was authorized by Order in Council, dated November 29, 2016.

Political activity subsequent to November 29, 2016

64. Over a period of twenty months after the approval of the Trans Mountain project, the applicant, Gooderham, continued his political efforts to persuade the Government of Canada to reconsider proceeding with the project.

65. Gooderham’s principal political activity during this twenty-month period between November 2016 and July 2018 was preparing and sending carefully researched papers to elected Members of Parliament, including to his own Member of Parliament, Joyce Murray, and to several Members of the B.C. Legislature, including to his own MLA, David Eby, and to other individuals who might be in a position to influence the course of the public discussion.

66. On December 9, 2016, ten days after authorizing the construction of the Trans Mountain Project, the Government of Canada released the Pan-Canadian Framework on Climate Change, described as a “national climate plan”. The published document purported to show how Canada’s total emissions could be reduced to 523 Mt by 2030, to meet the Paris Agreement emissions reduction commitment. The applicant, Gooderham, carefully examined the published document. He subsequently also examined the updated version of the Pan-Canadian Framework that was published a year later, on December 29, 2017, when the government’s promised future reductions under that plan, in revised form, were included in new report called Canada’s 3rd Biennial Report.

67. Based on his examination of the government’s promised future emissions reduction policies contained in the Framework document and the updated version released on December 29, 2017, and taking into account his understanding of the existing constraints on achieving rapid emissions cuts in the Canadian economy, particularly with projected substantial growth in oil sands emissions, Gooderham concluded that the Pan Canadian Framework offered no reasonable assurance, or no assurance at all, that Canada would be able to meet its 2030 emission reduction target.

68. On March 27, 2018, the Auditor General of Canada in collaboration with the auditors general of all ten provinces (except Quebec) issued a joint report entitled Perspectives on Climate Change in Canada: A Collaborative Report from the Auditors General. The report stated that “Meeting Canada’s 2030 target will require substantial effort and actions beyond those currently in place or planned.” It further stated: “It is unclear how Canada will meet this target”. Gooderham reviewed the report shortly after it was published.

69. In the context of what any Canadian citizen could do to contribute to alleviating the further advance of the global peril, the most salient emitting activity in Canada is the projected expansion of oil sands production in Alberta to 2030 and 2040. The projected increase in the annual level of oil sands emissions between 2015 and 2030 is 44 Mt, which is projected to be the largest source of emissions growth in Canada over that period, compared to any other industry or any other economic sector. The material question is whether that increase can be reconciled with obtaining a 200 Mt reduction of Canada’s total emissions over the next decade, which will have to be obtained from Canada’s other economic sectors.

70. Canada’s second largest emitting sector is transportation. Based on the Government of Canada’s most recent projections, taking into account current policies implemented up to September 2017, total transportation sector emissions across Canada between 2015 and 2030 are expected to decline by only 18 Mt. Even if other “additional measures” promised under the government’s most recent emissions reduction plan published on December 29, 2017, are fully implemented, the total projected reduction in the entire transportation sector will still be only 32 Mt by 2030, measured against the 2015 level. (The promised additional transportation measures are not yet implemented and in many cases have not yet been developed). Emissions growth in the oil sands sub-sector between 2015 and 2030 will negate all the emissions cuts that Canada hopes to achieve from the entire transportation sector across Canada, which includes all passenger cars, all road freight transport, rail, domestic aviation, and marine shipping.

71. In the global context, Canada’s planned expansion of oil sands production to 2030 is gravely consequential. The available evidence is unequivocal that global oil consumption must start to decline by about 2020, and decline from the 2014 level of 90.6 million bpd to about 74 million bpd by 2040, or less, if surface warming is to be limited to less than 2°C above the pre-industrial level.

72. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projections show that under current policies (also referred to as business-as-usual projections) global oil consumption is expected to rise to 103.5 million bpd by 2040, a 12.9 million bpd increase above the 90.6 million bpd level in 2014. Only six or seven major oil producing countries have large enough oil reserves to satisfy that increase in demand. Canada is one of those suppliers.

73. To stay within the 2°C pathway, global suppliers would have to cut production levels by at least 30 million bpd by 2040, below the currently projected level for 2040.

74. The Government of Canada’s recent projections show that oil sands production is expected to increase by 1.7 million bpd between 2015 and 2030, with additional growth during the following decade to 2040. That planned expansion is inconsistent with a 2°C world.

75. By the end of July 2018, Gooderham had concluded that there remained no realistic prospect that the Government of Canada would be persuaded or induced to reconsider its decision to proceed with construction of the Trans Mountain Project and the Line 3 expansion project, which together will provide sufficient new pipeline capacity to transport about 50% of the total projected expansion of oil sands production between 2015 and 2040.

Belief on reasonable grounds

76. By the end of July 2018, and for at least a full year before that, Gooderham had come to believe that there is no reasonable likelihood that global emissions can be reduced fast enough to keep the increase in global surface warming within the 2°C pathway. His belief is that while the 2°C commitment is still technologically and economically feasible if very stringent carbon reduction policies are adopted and implemented in multiple countries, any estimation of that occurring is conjectural because it depends on evidence that does not exist.

77. The available evidence shows that even if all countries that have made commitments (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement fully implement all of their promised reductions, the world will still be on a pathway to a temperature increase exceeding 3°C. The existing NDCs account for only about one third of the reductions needed to stay within the 2°C pathway. The remaining emissions gap is 13.4 GtCO2 of additional reductions. That amount is twice the magnitude of all the existing reduction commitments that have been given by the signatories to the Paris Agreement, including by the wealthiest and the most technologically advanced economies. There is no existing plan that explains how the 13.4 GtCCO2eq emissions gap can be satisfied.

78. Gooderham’s belief is that adequate emissions reduction cannot be achieved within the next twelve years to keep warming within the 1.5°C pathway.

79. Gooderham’s belief is that by 2030 the earth’s climate system will be irrevocably committed to surface warming of at least 1.5°C, and that we have no assurance that by the end of the decade we will not be committed to more than 2°C of warming. We will not know the answer to the second question until well into the next decade, when we may see whether, and to what extent, emitting countries have taken any of the essential and exceptional steps required to address the emissions gap. Essential steps would include halting further growth of global oil consumption, and the beginning of a substantial decline in oil demand by 2020.

80. The warming of the earth is already far advanced. The impacts are already degrading human and natural systems. The losses are irreversible. We know that, if we act to the full extent of our capacities now and during the next twelve years, we have it in our power to halt this unfolding peril and curb the losses. We will not be able to avoid the further losses that will be caused as surface warming increases from the current level of 1°C to 1.5°C, and we probably cannot curb the deepening losses that will occur as warming moves above 1.5°C to 2.0°C. But our opportunity is to at least limit the further loss and peril as warming moves significantly above 2°C. The scientific evidence is clear that the greatest losses and risks to human systems and natural systems will occur as warming approaches and then exceeds the 2°C. That is the immediate peril we can act to avoid.

[12] The Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46 (the “Code”), preserves common law justifications, excuses or defences in so far as they have not been altered by or are inconsistent with the Code or another Act of the Parliament of Canada. “Necessity” is a common law defence when “non-compliance with the law” is excused by an emergency “or justified by the pursuit of some greater good”.

[13] In Perka v. The Queen, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 232 [Perka], Dickson J. (later C.J.C.) quoted from George Fletcher, Rethinking Criminal Law (1978) as follows:

… The lost alpinist who on the point of freezing to death breaks open an isolated mountain cabin is not literally behaving in an involuntary fashion. He has control over his actions to the extent of being physically capable of abstaining from the act. Realistically, however, his act is not a “voluntary” one. His “choice” to break the law is no true choice at all; it is remorselessly compelled by normal human instincts. This sort of involuntariness is often described as “moral or normative involuntariness”.

[14] Justice Dickson then wrote:

I agree with this formulation of the rationale for excuses in the criminal law. In my view this rationale extends beyond specific codified excuses and embraces the residual excuse known as the defence of necessity. At the heart of this defence is the perceived injustice of punishing violations of the law in circumstances in which the person had no other viable or reasonable choice available; the act was wrong but it is excused because it was realistically unavoidable.

[15] In R. v. Latimer, 2001 SCC 1 [Latimer], the Court at para. 28 wrote:

Perka outlined three elements that must be present for the defence of necessity. First, there is the requirement of imminent peril or danger. Second, the accused must have had no reasonable legal alternative to the course of action he or she undertook. Third, there must be proportionality between the harm inflicted and the harm avoided.

[16] In determining whether the choice of an accused to break the law “was no choice at all” the court is bound to consider the full evidentiary context relating to the nature of the peril, the gravity of the peril measured in terms of its consequences, the probability or certainty of its onset, and the time remaining to avoid it. In the hypothetical case of the “lost alpinist” who faced “imminent death” if shelter was not found by illegally breaking into a cabin, it would be “unthinkable” to choose not to act in disobedience of the law.

[17] In Latimer at para. 32, the court wrote:

Before applying the three requirements of the necessity defence to the facts of this case, we need to determine what test governs necessity. Is the standard objective or subjective? A subjective test would be met if the person believed he or she was in imminent peril with no reasonable legal alternative to committing the offence. Conversely, an objective test would not assess what the accused believed; it would consider whether in fact the person was in peril with no reasonable legal alternative. A modified objective test falls somewhere between the two. It involves an objective evaluation, but one that takes into account the situation and characteristics of the particular accused person. We conclude that, for two of the three requirements for the necessity defence, the test should be the modified objective test.

[Emphasis added.]

[18] The peril of global warming above a 2°C threshold since pre-industrial times is subjectively believed by the applicants to be imminent and to lead to catastrophic climate change. Such peril is objectively and scientifically verifiable based on the evidence the applicants intended to offer, if the necessity defence were held to be viable. Such a peril is “imminent” once it “is established at the relevant point in time that the realization of the peril, however far off it might be, is not thereby any less certain and inevitable”: Case Concerning Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project (Hungary v. Slovakia, [1997] I.C.J. Rep. 7. Therefore continued development of oil sands production must be halted because not to do so creates “an existential risk”. As a matter of law, that grave peril is imminent and the first part of the necessity defence is therefore met.

[19] In reasons for judgment indexed at 2018 BCSC 874, I considered an application in this proceeding by Thomas Sandborn to determine if the defence of necessity was available to him. The application was dismissed and at para. 23 of the reasons there is the following:

In my opinion an argument that there was no reasonable legal alternative but to disobey the injunction cannot be sustained. All orders of this Court are subject to variation or to appellate review. No attempt was made to seek a variation of the injunction order nor to appeal it.

[20] If the applicants were to have applied to this Court to dissolve the injunction, they would have informed the court that their intention, once the injunction was dissolved, was to go to the Burnaby Terminal of Trans Mountain Pipeline and block access to the work at that site. The applicants submit it is unimaginable that this Court, in those circumstances, would have dissolved the injunction.

[21] At para. 29 of the same reasons for judgment, there is the following:

Lastly, I will observe that what seems to have been forgotten when the excuse of necessity is argued in this instance is that we live in a robust democracy. Governments change their policies when public pressure is brought to bear and governments themselves not infrequently leave office following elections and therefore policies of one kind or another change.

[22] The applicants argue that any meaningful opportunity to exercise political influence to halt the expansion of the pipeline or to challenge plans to expand oil sands production effectively came to an end when the OIC was signed in November 2016. The OIC was eventually quashed by the Federal Court of Appeal in Tsleil-Waututh Nation v. Canada (Attorney General), 2018 FCA 153 [Tsleil-Waututh], but that decision rested on grounds related to the failure of the National Energy Board (“NEB”) to address marine related environmental risks and the inadequacy of the consultation process with Indigenous peoples. On the other hand, the applicants’ objections to the pipeline enhancement, and increased production from the Alberta oil sands, relate to greenhouse gas emissions, which issues were not addressed by the NEB nor by the Federal Court of Appeal. The directions given to the NEB for its further inquiries, following the quashing of the OIC, do not address emissions issues. An application to this Court to consider the emissions issues would have been met with a response that it was an improper collateral attack on the injunction.

[23] That applicants submit that, once the pipeline had been authorized by the OIC in November 2016, “all legitimate and meaningful avenues for Canadian citizens to question and challenge the project had been shut down”. The “extreme gravity” of the threat posed by global warming beyond 2°C left the applicants with “no viable or reasonable legal alternative,” but to “act by attempting to block construction work at the Burnaby Terminal”.

[24] The evidence proposed to be led if the necessity defence were permitted would demonstrate that if global temperatures rise 2°C above pre-industrial levels, the losses to human and natural systems will be massive and destructive in comparison to “any harm caused by disobeying a court order” and thereby preventing or delaying the construction of the pipeline.

[25] The applicants acknowledge that in MacMillan Bloedel v. Simpson (1994), 90 B.C.L.R. (2d) 24 [MacMillan Bloedel], Chief Justice McEachern held that the defence of necessity could not be raised by protesters for breach of an injunction. Chief Justice McEachern wrote at paras. 45-46:

45 In my judgment, this defence cannot be applied in this case for at least two reasons. First, the Defendants had alternatives to breaking the law, namely, they could have applied to the court to have the injunction set aside. None of them did that prior to being arrested. I do not believe this defence operates to excuse conduct which has been specifically enjoined. By granting the order, the court prohibited the very conduct which is alleged against the Defendants. An application to the court, which could be heard on fairly short notice, would have determined whether the circumstances were sufficient to engage the defence of necessity.

46 Second, I do not believe the defence of necessity can ever operate to avoid a peril that is lawfully authorized by the law. M & B had the legal right to log in the areas in question, and the defence cannot operate in such circumstances.

[26] The applicants nevertheless submit that after applying the “moral or normatively involuntary” test, they clearly had “no choice.” They ask: how can it make any difference that the peril which is so stark in its consequences, is authorized by law? Further, the injunction does not “authorize the peril”. The peril is the increase of emissions from expanding oil sands production. The pipeline facilitates that expansion. The injunction has a narrow focus (unlawful interference at the work sites), and it was granted without any evidence or consideration of whether the pipeline project would facilitate an increase of oil sands production, or scientific evidence about the perils of climate change. Further, when considering whether the pipeline construction was lawful, it must be recalled that the OIC did not “authorize” the peril; it authorized the construction of the pipeline.

[27] The applicants present various examples of cases from jurisdictions outside of Canada in which courts have considered a defence of necessity in the context of climate change.

[28] In the Washington State decision of Washington v. Brockway, 2018 Wash. App. Lexis 1275, the Court allowed the defendants to introduce evidence to support the defence of necessity. However, at trial, the defence was not left with the jury, as the trial judge determined that there was insufficient evidence, such that no reasonable trier of fact could find the test met, on the “no reasonable alternative” branch of the American test for necessity. This determination was upheld on appeal (Court of Appeals Div. I, Unpublished Opinion, May 29, 2018).

[29] In State v. Klapstein, 2018 W.L. 1902473, three individuals travelled to a petroleum pipeline valve station. The pipeline was carrying oil from the oil sands in Canada. The individuals cut a chain securing a valve and then contacted Enbridge, the company operating the pipeline, to inform it of what was occurring and to provide it with an opportunity to shut down the pipeline valve remotely. The individuals were charged with various criminal offences. At trial the District court granted the defendants’ request to present evidence on the defence of necessity:

“The court’s grant [of a request to present evidence on the defence of necessity] is not unlimited and the Court expects any evidence in support of the defence of necessity to be focused, direct and presented in a non-cumulative manner.”

The State appealed this decision. The appeal was dismissed and the defendants were acquitted at trial.

[30] In the United Kingdom, one case to date has been successful when raising the defence of necessity in the context of climate change. In R. v. Hewke (unreported), activists protested against a coal-fired power plant, causing £30,000 property damage. The activists raised the defence of “lawful excuse” and claimed that the harm inflicted, that of property damage, was less than the harm they intended to avoid, that of climate change. Evidence was admitted from experts that imminent harm to the planet was caused by coal-fired power plants. The jury acquitted the six accused.

[31] The applicants before me conclude their submissions with the following:

[The proverb] “necessity knows no law”… encapsulates the fundamental tension between legal frameworks that seek to normalize social behavior and urgent action in response to unpredictable events. The defence of necessity provides a mechanism to accommodate this tension and fosters the law’s adaption to unforeseen circumstances. . . Necessity augments legal flexibility. . . As a result, the law’s resilience to socio-ecological changes is enhanced.

For these reasons, the Applicants respectfully submit that this court should permit the applicants to raise the defence of necessity to the within charges. Doing so will underwrite the dialectic between certainty and flexibility on which the rule of law must function.

[32] The expansion of the pipeline “is a state action fomented by the Government of Canada”. The expansion of the pipeline, now owned by the Government of Canada, constitutes state action imperiling citizens’ rights “to a stable climate within which life may be maintained”.

[33] Section 7 of the Charter reads:

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.

[34] The fundamental right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is protected by s. 7.

[35] The Crown has taken the position that persons arrested at the time the applicants were arrested, if convicted, ought to be sentenced to 28 days in jail. The liberty interest of the applicants is thus engaged.

[36] The principles of fundamental justice are “the shared assumptions upon which our system of justice is grounded” and establish “the basic norms for how the state deals with its citizens”: Canadian Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law v. Canada (Attorney General), 2004 SCC 4 at para. 8 [Canadian Foundation]. A climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to all citizens. These are legal principles, “vital or fundamental to our societal notion of justice”: Rodriguez v. British Columbia (Attorney General), [1993] S.C.R. 519, at 590.

[37] In the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, 195 nations, including Canada, explicitly recognized “the linkage between human rights and climate change”. At the 1972 United Nations conference on the human environment Canada and “the global community” endorsed an “explicit link between environmental protection and the fulfilment of human rights, including the right to life”.

[38] The 1972 Stockholm declaration on the human environment endorsed by 112 countries recognized that the environment is essential to the enjoyment of basic human rights and that there is a solemn duty to protect it for present and future generations.

[39] The 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on climate change expressly referred to the Stockholm declaration and acknowledged that human life is threatened by climate change. Canada committed to achieving the Convention’s objective of stabilizing atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations at a level that “would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system … within a timeframe sufficient” to avoid threatening certain functions necessary to life.

[40] In 2008, the members of the United Nations Human Rights Council affirmed that climate change has had an adverse impact on the full and effective enjoyment of human rights and recognized that a stable climate system is necessary for the realization of human rights, including the right to life.

[41] In 2015, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights observed that states “have an affirmative obligation” to take effective measures to prevent and redress these climate impacts, and therefore, to mitigate climate change. The right to life is a “supreme right” and should not be interpreted narrowly. By ratifying the Paris Agreement, Canada acknowledged that, to achieve the objective of sustaining human life, the global average temperature ought to be kept “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels “to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change”.

[42] The United States Declaration of Independence reads, in part, that: “we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life liberty and the pursuit of happiness”. The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution established a citizen’s due process rights in criminal proceedings, inter alia “… Nor shall any person … be deprived of life liberty or property without due process of law”.

[43] In 2007, the United States Supreme Court in Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497, 499 (2007), held that “[t]he harms associated with climate change are serious and well recognized”.

[44] The applicants rely on “the U.S. Juliana litigation” (217 F. Supp 3d 1224, 2017 U.S. Dist. Lexus 89000), in which the plaintiffs are suing the United States and various government officials, asserting they have known for decades that carbon dioxide “pollution” has been causing catastrophic climate change and have failed to take action to curtail fossil fuel emissions. The plaintiffs allege that the U.S. government and its agencies have taken action, or failed to take action, that has resulted in increased carbon pollution through the use of fossil fuels.

[45] The relief sought in the Juliana litigation includes:

(a) A declaration that the defendants have violated and are violating the plaintiffs’ fundamental constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property by substantially causing or contributing to a dangerous concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and that, in so doing, defendants dangerously interfere with a stable climate system required by the nation and plaintiffs alike; and

(b) An injunction restraining the defendants from further violations of the Constitution of the United States.

[46] In response to the claim in Juliana, the United States government has conceded that:

(a) For over fifty years some officials and persons employed by the federal government have been aware of a growing body of scientific research concerning the effects of fossil fuel emissions on atmospheric concentrations of CO2—including that increased concentrations of atmospheric CO2 could cause measurable long-lasting changes to the global climate, resulting in an array of severe deleterious effects to human beings, which will worsen over time.

(b) Global atmospheric concentrations of CO2, methane, and nitrous oxide are at unprecedentedly high levels compared to the past 800,000 years of historical data and pose risks to human health and welfare.

(c) From 1850 to 2012, CO2 emissions from sources within the United States (including from land use) comprised more than 25 percent of cumulative global CO2 emissions.

(d) There is a scientific consensus that the buildup of green house gases (“GHGs”) (including CO2) due to human activities (including the combustion of fossil fuels) is changing the global climate at a pace and in a way that threatens human health and the natural environment.

(e) CO2 emissions are currently altering the atmosphere’s composition and will continue to alter Earth’s climate for thousands of years.

(f) In 2013, daily average atmospheric CO2 concentrations (measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory) exceeded 400 ppm for the first time in millions of years [and in 2015 reached] levels unprecedented for at least 2.6 million years.

(g) The Earth has now warmed about 0.9°C above pre-industrial temperatures.

(h) Climate change is damaging human and natural systems, increasing the risk of loss of life, and requiring adaptation on larger and faster scales than current species have successfully achieved in the past, potentially increasing the risk of extinction or severe disruption for many species.

(i) Current and projected atmospheric concentrations of six well-mixed GHGs, including CO2, threaten the public health and welfare of current and future generations, and this threat will mount over time as GHGs continue to accumulate in the atmosphere and result in ever greater rates of climate change.

(j) Human activity (in particular, elevated concentrations of GHGs) is likely to have been the dominant cause of observed warming since the mid-1900s.

(k) Climate change is likely to be associated with an increase in allergies, asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke, heat-related morbidity and mortality, food-borne diseases, injuries, toxic exposures, mental health and stress disorders, and neurological diseases and disorders.

[47] The U.S. District Court concluded that:

Plaintiffs have alleged, and federal defendants have since admitted, that human induced climate change is harming the environment to the point where it will relatively soon become increasingly less habitable causing an array of severe deleterious effects to them which includes an increase in allergies, asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke, heat related morbidity and mortality, food-borne disease, injuries, toxic exposures, mental health and stress disorders, and neurological diseases and disorders. These are concrete, particularized, actual or imminent injuries to the plaintiffs that are not minimalized by the fact that vast numbers of the populace are exposed to the same injuries. It would surely be an irrational limitation on standing which allowed isolated incidents of deprivation of constitutional rights to be actionable, but not those reaching pandemic proportions.

[48] The District Court of Oregon’s conclusion that a climate system capable of sustaining human life “is fundamental to the enjoyment of U.S. Constitutional Fifth Amendment rights to ‘life, liberty and property’” is supported by a growing body of “foreign jurisprudence”.

[49] In 2015, the Lahore High Court in Ashgar Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan, W.P. No. 25501/2015, declared: “Climate Change is a defining challenge of our time and has led to dramatic alterations in our planet’s climate system. ... On a legal and constitutional plane this is clarion call for the protection of fundamental rights of the citizens of Pakistan.’’ The Lahore High Court invoked the right to life and the right to dignity protected by the Constitution of Pakistan. The court spoke of the international principles that call for a “move to Climate Change Justice.” It directed the government of Pakistan to identify and begin implementing climate change adaptation measures to protect Pakistani citizens and to establish a Climate Change Commission to help the court monitor progress and achieve compliance with guidelines.

[50] In 2015, The Hague District Court in the Netherlands adjudicated a complaint by 900 Dutch citizens after the government “decided to retreat from its international commitments to address climate change”. While acknowledging that the Netherlands’ treaty commitments could not be directly enforced by the plaintiffs in that case, the court concluded that these international commitments create “the framework for and the manner in which the State exercises its powers” and thus inform the government’s duty of care to its citizens. The court then found that “[d]ue to the severity of the consequences of climate change ... the State has a duty of care to take mitigation measures”.

[51] In T. Damodhar Rao v. Municipal Corp. of Hyderabad, 1987 A.I.R (AP) 171, the High Court of Andhra Pradesh wrote:

Examining the matter from the ... constitutional point of view, it would be reasonable to hold that the enjoyment of life and its attainment and fulfilment guaranteed by Art. 21 of the Constitution embraces the protection and preservation of nature’s gifts without [which] life cannot be enjoyed. There can be no reason why practice of violent extinguishment of life alone should be regarded as violative of Art. 21 of the Constitution. The slow poisoning by the polluted atmosphere caused by environmental pollution and spoliation should also be regarded as amounting to violation. . . .

[52] Courts in Bangladesh, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Costa Rica have also recognized a sufficiently healthy environment as inherently linked to the right to life and other fundamental rights.

[53] In Latimer, under the heading “the availability of the defence of necessity”, the Court wrote of the three “requirements” that must each be met to establish the defence. I quote paras. 26 through 31:

26 We propose to set out the requirements for the defence of necessity first, before applying them to the facts of this appeal. The leading case on the defence of necessity is Perka v. The Queen, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 232. Dickson J., later C.J., outlined the rationale for the defence at p. 248:

It rests on a realistic assessment of human weakness, recognizing that a liberal and humane criminal law cannot hold people to the strict obedience of laws in emergency situations where normal human instincts, whether of self-preservation or of altruism, overwhelmingly impel disobedience. The objectivity of the criminal law is preserved; such acts are still wrongful, but in the circumstances they are excusable. Praise is indeed not bestowed, but pardon is ....

27 Dickson J. insisted that the defence of necessity be restricted to those rare cases in which true “involuntariness” is present. The defence, he held, must be “strictly controlled and scrupulously limited” (p. 250). It is well established that the defence of necessity must be of limited application. Were the criteria for the defence loosened or approached purely subjectively, some fear, as did Edmund Davies L.J., that necessity would “very easily become simply a mask for anarchy”: Southwark London Borough Council v. Williams, [1971] Ch. 734 (C.A.), at p. 746.

28 Perka outlined three elements that must be present for the defence of necessity. First, there is the requirement of imminent peril or danger. Second, the accused must have had no reasonable legal alternative to the course of action he or she undertook. Third, there must be proportionality between the harm inflicted and the harm avoided.

29 To begin, there must be an urgent situation of “clear and imminent peril”: Morgentaler v. The Queen, [1976] 1 S.C.R. 616, at p. 678. In short, disaster must be imminent, or harm unavoidable and near. It is not enough that the peril is foreseeable or likely; it must be on the verge of transpiring and virtually certain to occur. In Perka, Dickson J. expressed the requirement of imminent peril at p. 251: “At a minimum the situation must be so emergent and the peril must be so pressing that normal human instincts cry out for action and make a counsel of patience unreasonable”. The Perkacase, at p. 251, also offers the rationale for this requirement of immediate peril: “The requirement ... tests whether it was indeed unavoidable for the actor to act at all”. Where the situation of peril clearly should have been foreseen and avoided, an accused person cannot reasonably claim any immediate peril.

30 The second requirement for necessity is that there must be no reasonable legal alternative to disobeying the law. Perka proposed these questions, at pp. 251-52: “Given that the accused had to act, could he nevertheless realistically have acted to avoid the peril or prevent the harm, without breaking the law? Was there a legal way out?” (emphasis in original). If there was a reasonable legal alternative to breaking the law, there is no necessity. It may be noted that the requirement involves a realistic appreciation of the alternatives open to a person; the accused need not be placed in the last resort imaginable, but he must have no reasonable legal alternative. If an alternative to breaking the law exists, the defence of necessity on this aspect fails.

31 The third requirement is that there be proportionality between the harm inflicted and the harm avoided. The harm inflicted must not be disproportionate to the harm the accused sought to avoid. See Perka, per Dickson J., at p. 252:

No rational criminal justice system, no matter how humane or liberal, could excuse the infliction of a greater harm to allow the actor to avert a lesser evil. In such circumstances we expect the individual to bear the harm and refrain from acting illegally. If he cannot control himself we will not excuse him.

Evaluating proportionality can be difficult. It may be easy to conclude that there is no proportionality in some cases, like the example given in Perka of the person who blows up a city to avoid breaking a finger. Where proportionality can quickly be dismissed, it makes sense for a trial judge to do so and rule out the defence of necessity before considering the other requirements for necessity. But most situations fall into a grey area that requires a difficult balancing of harms. In this regard, it should be noted that the requirement is not that one harm (the harm avoided) must always clearly outweigh the other (the harm inflicted). Rather, the two harms must, at a minimum, be of a comparable gravity. That is, the harm avoided must be either comparable to, or clearly greater than, the harm inflicted. As the Supreme Court of Victoria in Australia has put it, the harm inflicted “must not be out of proportion to the peril to be avoided”: R. v. Loughnan, [1981] V.R. 443, at p. 448.

[Emphasis added.]

[54] In my opinion a “clear and imminent peril”, as that phrase has been employed in the authorities by which I am bound, cannot be demonstrated. The Court in Latimer ruled that the peril must be on the “verge of transpiring” (at para. 29). The applicants submit the evidence they intended to put before the court, if permitted, would demonstrate that without immediate remedial action, climate change will become irreversible and catastrophic damage to life on this planet will be inevitable. The subjective belief element of the modified objective test has clearly been met.

[55] On the evidence the applicants seek to offer, rising global temperatures, to a level that is catastrophic to life, is a process that has been happening over many decades. Despite a historical lack of initiative to curb emissions over these same decades, adaptive societal measures may be taken to prevent such a dire outcome. Whether government, private industry, and citizens take these measures is a contingency that takes these consequences outside of “virtual certainty” and into the realm of “foreseeable or likely” (Latimer, at para. 29). Thus, it cannot be said that the objective element of the modified objective test is satisfied

[56] I do not accept the proposition that the defence of necessity, according to the law of this province, provides an excuse for the unlawful conduct of the applicants in defying the injunction. In MacMillan Bloedel, Chief Justice McEachern, for the court, wrote the following, some of which I have already referred to when describing the applicants’ submissions:

43 The leading decision on the defence of necessity is Perka et al. v. The Queen, [1984] 2 S.C.R. 232 where Dickson J. (as he then was), writing for the Court, at p. 248 said:

[A] liberal and humane criminal law cannot hold people to the strict obedience of laws in emergency situations where normal human instincts, whether of self-preservation or of altruism, overwhelmingly impel disobedience.

44 In his judgment, however, Dickson J., made it clear that this unusual defence may be applied only in truly emergent circumstances, and only when the person at risk has no alternative but to break the law. This question was considered by my colleague Wood J. (as he then was) in Regina v. Bridges (1989), 48 C.C.C. (3d) 535 (B.C.S.C.), which was one of the abortion cases. At p. 541 Wood J. said:

Thus it can be seen that the defence of necessity which the defendants seek to raise rests on the footing that disobedience of the order of this court was necessary in order to avoid the imminent peril of harm resulting from the conduct of the plaintiff’s clinic which conduct was, and is in fact, lawful. This novel approach to necessity defies any description of the defence which I have been able to find in any recognized authority on the subject. On that basis alone, I must reject the notion that the defence of necessity can have any role to play in these proceedings.

45 In my judgment, this defence cannot be applied in this case for at least two reasons. First, the Defendants had alternatives to breaking the law, namely, they could have applied to the court to have the injunction set aside. None of them did that prior to being arrested. I do not believe this defence operates to excuse conduct which has been specifically enjoined. By granting the order, the court prohibited the very conduct which is alleged against the Defendants. An application to the court, which could be heard on fairly short notice, would have determined whether the circumstances were sufficient to engage the defence of necessity.

46 Second, I do not believe the defence of necessity can ever operate to avoid a peril that is lawfully authorized by the law. M & B had the legal right to log in the areas in question, and the defence cannot operate in such circumstances.

[Emphasis added.]

The applicants have attempted to find a means to evade those adamantine words, but I am bound by them.

[57] The applicants, as with the Defendants in MacMillan Bloedel, took no steps to seek an order to vary or set aside the injunction nor was it appealed. Therefore, the second branch of the necessity test, “no reasonable legal alternative”, cannot be met.

[58] Given that I have found the first two branches of the necessity test could not be established on the evidence, I need not enter into a proportionality balancing exercise on the third branch of the necessity test.

[59] They take the position that by defying the injunction they were challenging the OIC that authorized the enlargement of the pipeline. I do not agree that as a proper characterization of their conduct for the purposes of defining the necessity issue at their trial. Challenging the OIC may be effected, at least indirectly, through the democratic political process that prevails in Canada, and which influences the decisions of government, and in addition may be affected by adopting the judicial review approach reflected in Tsleil-Waututh. The applicants are dismissive of both alternatives to their defiance of the injunction. I do not agree they are entitled to place themselves outside both the law and the democratic process. As Dickson J. stated in Perka at 248:

It is still my opinion that, “[n]o system of positive law can recognize any principle which would entitle a person to violate the law because on his view the law conflicted with some higher social value”.