Articles Menu

September 14, 2021

When journalists interview me about old-growth forests, the hardest question to answer is “what is it like to be in one?” Standing in undergrowth so dense it’s hard to walk through with beams of sunlight piercing the tops of trees that were hundreds of years old before Europeans even arrived on this continent — how do you put this feeling into words?

The protection of ancient forests in what’s now known as British Columbia launched the environmental movement in this country decades ago, galvanizing hundreds of thousands of people worldwide. Despite the global renown of places like Clayoquot Sound and hard-won victories, old-growth logging continues at an alarming rate.

Decades after it began, the fight for these iconic ecosystems has ramped up again. Some things are different. The tools we have to organize and engage with people have improved, as have the photo and video technology we use to tell the story of what’s happening in the woods.

The protection of ancient forests, like all environmental justice, needs to centre justice for Indigenous Peoples

Recognition that our activism must respect and uplift the rights of Indigenous people has grown. More understand that the protection of ancient forests, like all environmental justice, needs to centre justice for Indigenous Peoples and the return of land to Indigenous Nations. Several First Nations are highlighting the links between ongoing colonialism and old-growth logging and calling for moratoriums on the practice in their territories.

Another thing that’s changed is the urgency.

Logging companies have already destroyed most of the forests with the biggest trees and the most biodiversity. The desire to protect what’s left is stronger than ever. From blockades at places like Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island and Argonaut Creek near Revelstoke to demonstrations outside the premier and forest minister’s offices to tens of thousands of messages to lawmakers, the public has made its opposition to old-growth logging clear. Even amidst a global pandemic that’s turned our lives upside down, the fate of these forests has become a more prominent issue.

In 2019, the surge in forest activism forced the BC NDP government to order the most comprehensive review of old-growth management ever done here. In April 2020, this Old-Growth Strategic Review panel submitted its acclaimed report to the government. It reinforced what our movement has been saying for years: the status quo isn’t sustainable and a paradigm shift is required.

Despite promising to implement the report’s recommendations and save the remaining old-growth, the government has taken little action. It missed most of the panel’s short-term deadlines and is opting instead for more process and review. This “talk-and-log” approach has resulted in the permanent and irreversible loss of some of Earth’s biggest trees and most phenomenal forest ecosystems. It’s not enough for B.C.’s premier to say the right things during elections or set up more panels and working groups. Without concrete action now to limit old-growth logging, words and commitments are meaningless.

The current government is the last that will have the chance to really protect what’s left of the irreplaceable forests in B.C. Read this publication to learn where things are at, what’s at stake and what’s required to end this battle once and for all.

The B.C. government and logging corporations lump together different kinds of forests and use vague language about the status of forests to downplay concerns around old-growth.

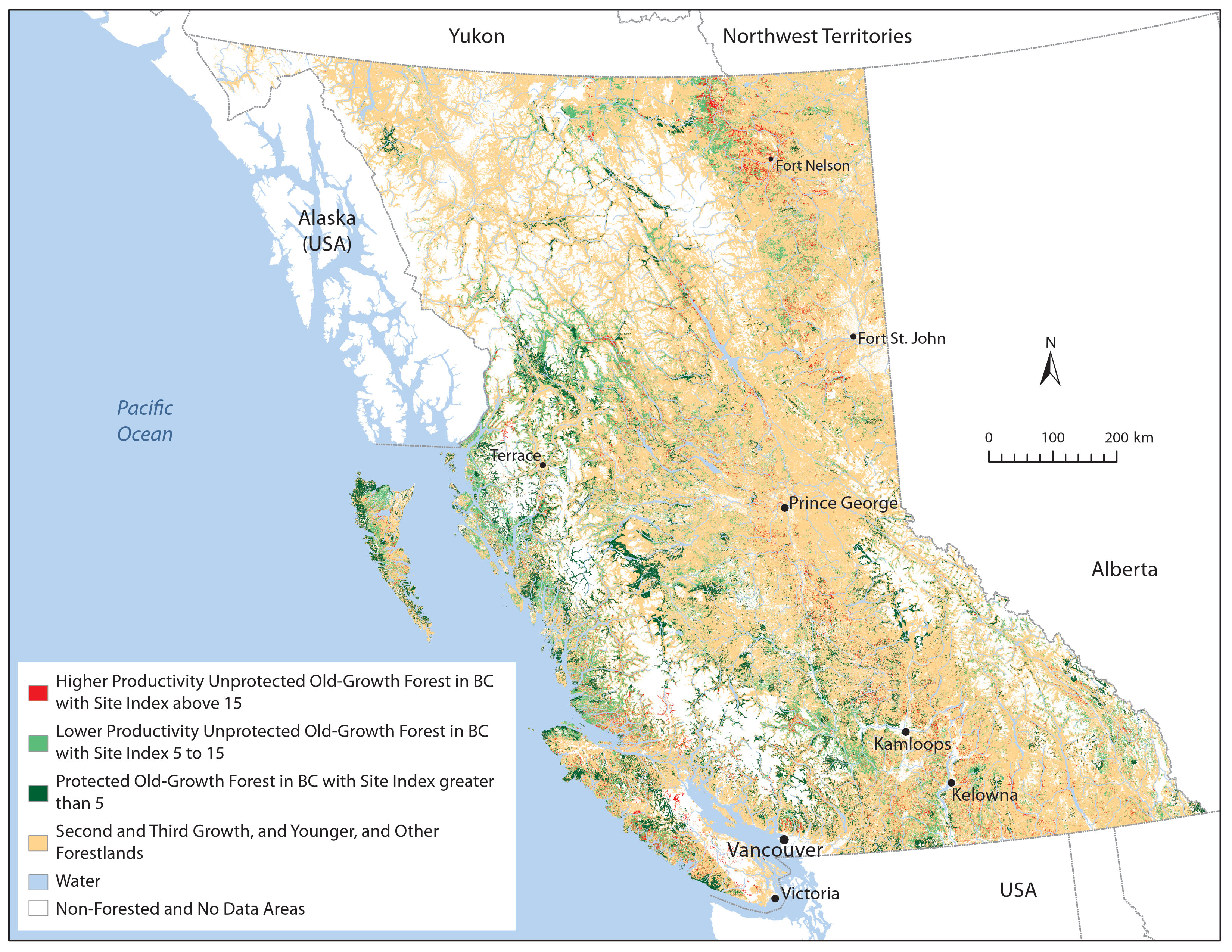

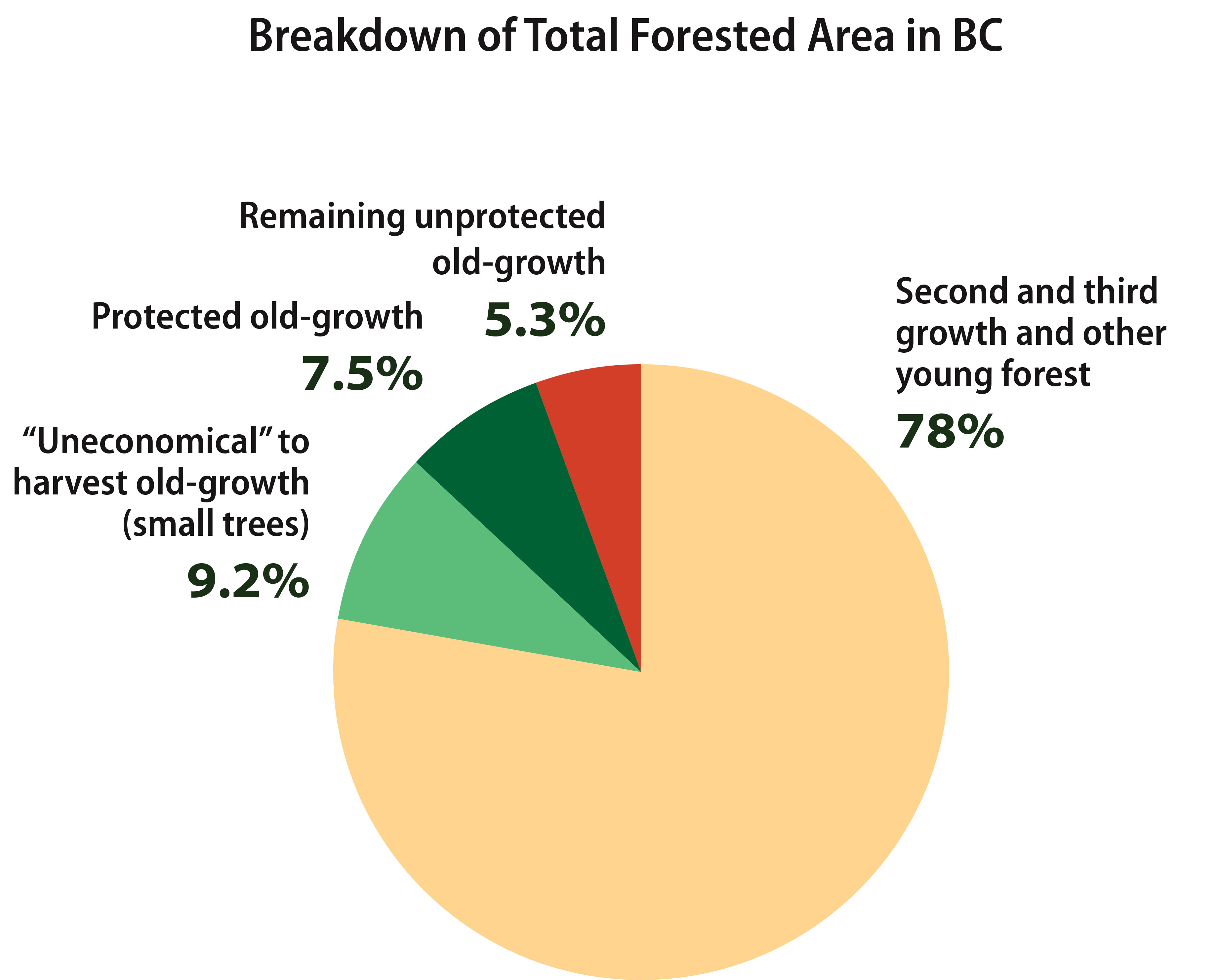

Here’s where things are really at. B.C.’s total land area is 94.47 million hectares. Of that, about 60 million hectares, the size of France and Germany combined, are forested. Of this area, a little over 13 million is old-growth in that it’s never been logged.

But here’s the thing: most of that 13 million hectares is not what people think of as old-growth forest.

Much of it is mountain or coastal bog forest with small, stunted trees, less biodiversity, less carbon storage capability and less of the value old-growth forests hold. These ecosystems matter, but they are not the iconic forests with huge trees we associate with old-growth.

These forests are less valuable to log, too. Industry and government define more than 40 per cent of all remaining old-growth — around 5.5 million hectares — as “uneconomical to harvest.” Another 4.5 million hectares are currently protected, and again, much of this is low-productivity forests with small trees. That leaves just over three million hectares.

The logging industry actively threatens these remaining three million hectares.

Of that three million, the most at-risk forests that require immediate deferral based on the Old-Growth Strategic Review panel’s criteria total about 1.3 million hectares or just 2.2 per cent of B.C.’s forests. It’s an area mapped by independent experts Rachel Holt, Karen Price and Dave Daust. This is far from a radical ask, it’s the bare minimum required to ensure ecological integrity.

And of the most productive old-growth forests with the biggest trees, only 415,000 hectares remain. Thats less than one per cent of the B.C.’s total forested area.

Approximately one-third of CO2 released from burning fossil fuels is absorbed by forests every year globally. In a heavily forested region like western Canada, we have a huge responsibility to ensure these ecosystems play this role.

And right now, they aren’t.

Between 1990 and 1994, forests across B.C. absorbed an average of more than 45 million tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere each year. But in 2003, forests in the province switched from being net absorbers of CO2 to net emitters. Between 2014 and 2018, they released more than 30 million tonnes on average. This doesn’t even include emissions from wildfires, which on their own can be two or three times as high as B.C.’s total emissions from all other sources in a bad fire year.

And here’s the kicker: despite being equal to almost half of B.C.’s total emissions, the provincial government doesn’t count emissions from logging in its “official” totals.

Many studies estimate that when a forest is logged, most of its carbon is released as CO2. When the trees are cut down, up to 46 per cent of the carbon in a forest is lost through waste and residue. An additional 22 per cent is lost as waste and residue at the mill. The transportation process from forest to mill and then mill to market offsets 17 per cent.

As little as 15 per cent of carbon in a forest is stored in products the trees within it are turned into. The cutblock, meanwhile, continues to release more greenhouse gases than it absorbs for at least a decade after it’s replanted.

Not only do most old-growth forests in Canada have a high capability to absorb and store carbon, but they also protect our communities from the impacts of climate change. Climate risks increase in areas with heavily logged landscapes. Old-growth forests have huge potential to help fight climate change and shield us from its impacts. However, industrial logging and government policy are squandering that potential.

In B.C.’s 2020 election campaign, Premier John Horgan said all forests belong to Indigenous Peoples. This followed his government’s passing of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act and some of the biggest commitments on Indigenous rights made to date by a government in Canada. Horgan has stressed the importance of protecting forests with Indigenous titleholders. Forest ministry employees have said new protections for old-growth need First Nations’ sign-off.

This is excellent, but it’s the standard that should be applied across the board. Indigenous free, prior and informed consent must be granted to protect lands in this country permanently, but it must also apply to logging — and that’s not happening today.

The government must expedite engagement with Indigenous communities, proactively seek direction around protecting critical forests within their territories and direct funding to support this process. It must then provide additional funding to offset any costs of setting forests aside and to invest in alternative economic opportunities. The BC NDP must ensure nations do not remain faced with the impossible choice between signing off on logging old-growth and turning down revenue and economic opportunity.

And in the meantime, old-growth logging must be put on hold. Because the tough reality is hundreds of hectares of non-renewable old-growth forest have been destroyed since Horgan promised to save it.

The pressure is rising. Bodies like the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs have called on the government to implement all recommendations of the Old-growth Strategic Review panel. Several First Nations, including the Sḵwxwú7mesh Nation, have demanded a halt to old-growth logging in our territories.

Upholding Indigenous rights and protecting old-growth forests go hand in hand. Accomplishing both means ensuring the best old-growth isn’t cut down while we talk. If the B.C. government is serious about keeping its promises on old-growth, it must immediately halt logging in at-risk old-growth forests.

Government and industry have spent decades pitting people who work in forestry and the general public concerned about old-growth forests against each other. They’ve worked to convince many loggers that environmentalists don’t care about them and to create the perception that sustaining rural economies requires logging the old-growth forests everyone loves.

Most people in the industry care about the environment. Most who identify as environmentalists want to see logging limited and transformed, not abolished. But this nuance is lost along with irreplaceable stands of old-growth and thousands of forestry jobs.

Meanwhile, the corporations that control the vast majority of forests continue to post record profits. These companies close mills, curtail operations and export raw logs for the exact same reasons they log in drinking watersheds, destroy endangered species habitat and cut down thousand-year-old trees. Their profits are their top priority and their decades of unsustainable harvest levels are catching up with them.

Governments talk about the need for balance between jobs and the environment, but it’s always been corporate profits at the expense of both. Since the late 1990s, declines and increases in logging rates no longer mean declines and increases in jobs in B.C. Over the past several decades, the amount of logging has gone up and down, while the number of forest industry jobs has steadily plummeted.

Reversing this is possible.

Other jurisdictions create more jobs and more dollars for the same amount of timber harvested. Many have outlined how forestry in B.C. could be made more sustainable by prioritizing local manufacturing and more democratic management of forests.

Building real solidarity at the community level, looking for solutions that work for ecosystems, distributing profits more equitably, maintaining good local jobs and respecting Indigenous sovereignty is crucial to replace status quo old-growth logging with a more respectful and long-lasting model.

To maintain healthy forests and, just as crucially, public trust, immediate measures to stop logging in at-risk old-growth forests are required. Multi-year or decade-long processes are no longer a luxury governments can afford because the most threatened forest ecosystems will be gone by then.

B.C.’s Old-Growth Strategic Review panel recognized this. That’s why they called for the deferral of all at-risk old-growth within six months to allow space and time for government-to-government talks with First Nations and long-term planning. The government missed this deadline, and that’s why tension and conflict continue — from blockades on logging roads to demonstrations outside the forest minister’s office.

Governments need to face the truth: changing old-growth policy slowly is now the same as doing nothing.

Immediate deferral of all at-risk old-growth forests is a necessary first step to demonstrate the provincial government’s commitment to its promised paradigm shift. But deferrals implemented to date fall short of this.

This first step must be accompanied by funding to compensate First Nations, municipal governments, contractors and workers for any lost jobs and revenue resulting from it. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown how quickly governments can mobilize resources when they need to — and they need to here. Once measures are in place to ensure old-growth ecosystems are no longer at risk of being lost, long-term planning must begin.

Priority number one has to be justice for and the return of land to Indigenous Peoples. The variety of wildlife is highest on Indigenous-managed lands, and Indigenous communities are the only societies that have managed forests sustainably on this continent. Restoration of that authority is our path forward.

Next, we must ensure all values provided by forests are balanced and end the prioritization of timber as the overriding thing we manage for. Finally, we must determine a sustainable operating level for the forest industry. Accepting that current logging levels are unsustainable is necessary to shift the entire model from maximizing volume and profits towards value and stability.

Because of how we’ve framed this conversation, this path seems like an ambitious one. But be they environmental or economic, the problems in the woods are rooted in an unbalanced and unhealthy way of relating to forests and getting this right is of global importance.

Like all good things, the momentum towards this has been built by people, and a better future for forests in B.C. and across Canada will be won by us too.

Commitments and promises don’t stop chainsaws from cutting into thousand-year-old trees and falling irreplaceable forests — only the provincial government changing laws does that. Please raise your voice and call on your government to:

Join the call on the B.C. government to keep its promise and protect old-growth forests. Sign our petition.

[ Photo top: Nuchatlaht Territory, Nootka Island ]