Articles Menu

Apr. 7, 2025

“Freedom for the pike is death for the minnows.” — Historian R.H. Tawney

Donald Trump’s world-rocking tariffs are possible only because of the raging force of discontent drowning U.S. democracy.

That fabled global economic enterprise called “normal” has sunk to the bottom of the ocean. But as members of Trump’s angry base see their hero derail the stock market and jeopardize their savings and spending power, their loyalty hardly wavers.

After all, they did dare him to flex. In the weeks running up to so-called “Liberation Day,” surveys found most Americans were leery of Trump’s tariff vows, heeding experts predicting the economy would suffer. But among a key segment of Trump’s hard-core base — white, non-college-educated men — more believed tariffs would restore the country’s manufacturing base. Their attitude: bring them on.

With such revolutionary forces in play, it is eerie to find ourselves just next door, in the middle of our own federal election, hearing scant alarm about the future of Canada’s democracy. It’s as if our elites running for office wish to ignore the backlash against elites that is sweeping the United States and many other countries.

Right now Trump’s abuse of Canada has focused our attention on a shared external enemy. But whichever party leader wins — the national banker or the career creature of Parliament — he will face a citizenry restlessly polarizing as the wealth gap widens and paths to a better life constrict. Politics as usual won’t cut it. Consider the current state of the U.S. Democratic party, for example. The liberal power structure that embraced markets, technology and credentialism sits in stunned disarray.

To understand the tsunami of discontent still building, every Canadian politician — and citizen — would do well to read the left-wing U.S. philosopher Michael Sandel, one of the first to identify the swelling force. He also recognized right-wing populism for what it is — “a response to a political failure of historic proportions.”

In his writings and talks, Sandel has advised opponents to Trump to practise “an economy of outrage.” It must be not only disciplined but guided by an alternative political project: a renewal of democratic discourse that addresses obscene inequality, the loss of community and the need for a new kind of patriotism.

But this discourse, he argues, will not bear any fruit without a sober assessment of the entirely legitimate grievances that have filled the Trump balloon or, for that matter, fuelled Pierre Poilievre’s companion populist crusade in Canada.

Sandel has been described as “the most formidable critic of free-market orthodoxy in the English-speaking world.” Born in Minnesota and raised in California, the Harvard academic speaks to the United States’ turmoil with a rare rabbinical wisdom. And clarity.

Sandel’s analysis traces the roots of the United States’ “Second Revolution” to the calculated abandonment of working people that began in the 1970s and ’80s with the end of the New Deal. That’s when Democratic elites from Bill Clinton to Barack Obama joined Republicans in embracing unfettered markets as the new economic God. They cut taxes for the rich and moved manufacturing overseas. A university education, they advised, was the only way to get ahead.

In his 1996 book Democracy’s Discontent, Sandel warned that this idolatrous enthusiasm for laissez-faire economics and credentialism would create great anxiety and not end well for workers or democracy.

In particular, he questioned the new faith in meritocracy, the idea that what you earn depends on what you learn. Meritocracy, he argued, had limits. For starters, it pointedly ignored those born poor. Secondly, the idea encouraged those who succeeded with their credentials to believe that their success was all their own doing. It also implied that those left behind deserved their fate. He thought such sentiments could rip apart democracies.

Sandel then spelled out the fateful consequences. Those without degrees (two-thirds of America) would increasingly feel they no longer had a voice in democracy and that the moral fabric of their communities was unravelling.

Sandel concluded that these “inchoate anxieties” could harden into polarization and anger that “could cast a shadow over the future of democracy itself.”

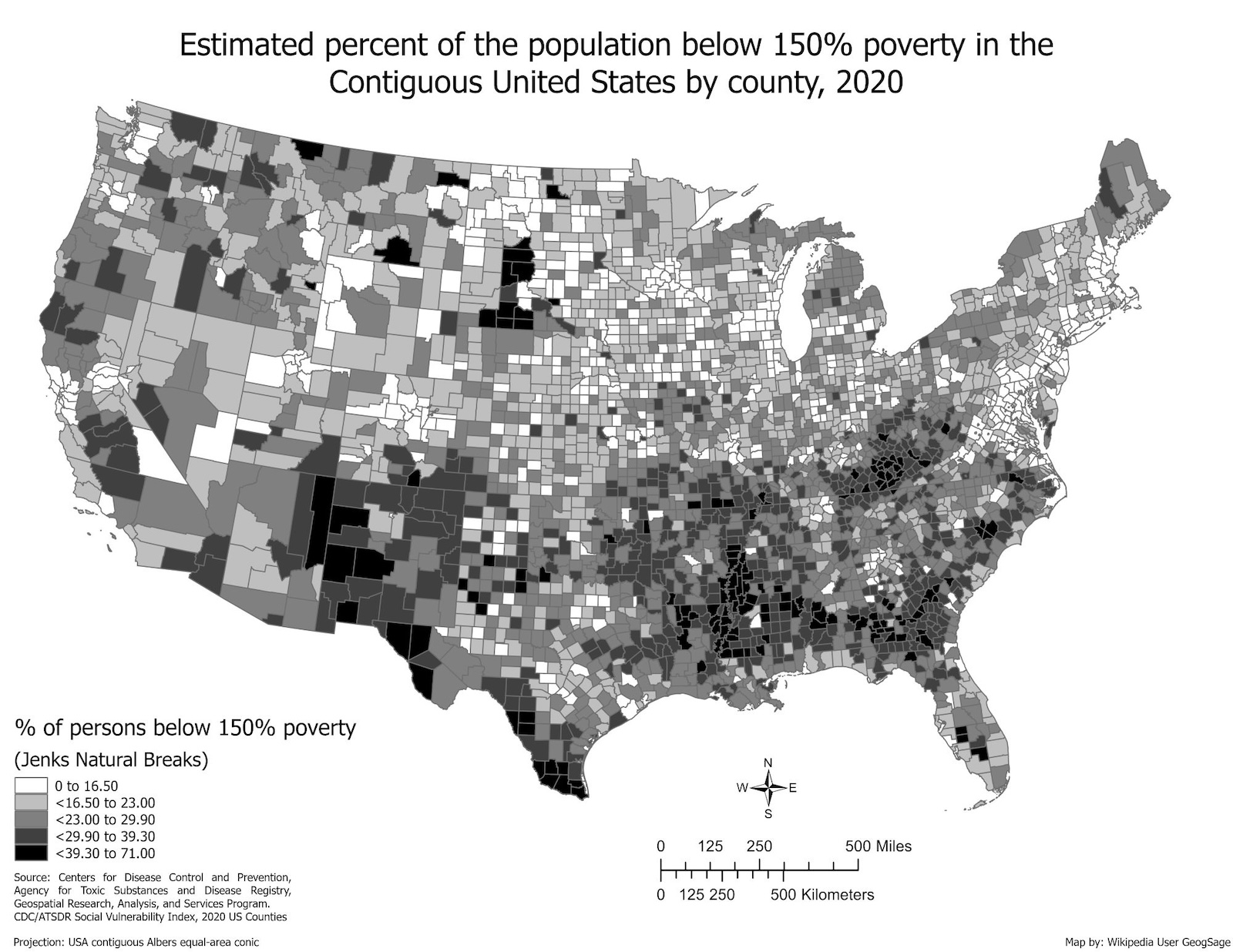

To appreciate the prescience of Sandel’s critique, let’s briefly review the appalling trends on income inequality, life expectancy, community engagement and institutional trust.

They tell a story of pain, rootlessness, abandonment, humiliation and loss of faith in democratic institutions. These emotions propelled Trump’s revolution.

According to the Wall Street Journal, just 10 per cent of U.S. households now make more than $250,000 a year. Incredibly, they now account for nearly half of all consumer spending. That’s an almost medieval reality.

Since 1976 real wages for Americans without a college degree (that’s the majority of Americans) have steadily shrunk with incredible social consequences.

The historian Peter Turchin points out that a worker earning an average wage in 1976 needed to work 150 hours to pay for one year of college at an average cost of $617.

In 2016 that same worker needed to put in 500 hours (three times longer) to pay for a yearly tuition of $8,804.

Meanwhile the pay of corporate executives has skyrocketed, making a mockery of honourable work. The corporate elite earned 399 times as much as an ordinary U.S. worker in 2021.

Taxes on corporations and billionaires now hover at their lowest levels since the 1920s.

The aging political system that celebrated credentials and ignored these trends now looks positively sclerotic.

About 45 per cent of U.S. politicians are over the age of 60. A gerontocracy now rules a plutocracy. In contrast, European politicians are getting younger.

Not surprisingly, economic inequality combined with a geriatric political class has led to a precipitous loss of faith in institutions.

According to Gallup, 70 per cent of Americans no longer have faith in the U.S. Supreme Court, banks, public schools, the presidency, large technology companies or organized labour.

Newspapers, the criminal justice system, television news, big business and Congress stand as the least trusted.

Faith in the U.S. Congress has fallen into single digits.

Accompanying this loss of faith has been a terrifying erosion of community. The number of Americans reporting no close friends has jumped from three per cent of the population to 24 per cent since 1990.

All in all, Americans with no college education now participate less often in community life, are less civically active and have fewer close friends than those with four-year college degrees.

Illiteracy has become such a common reality that 130 million Americans cannot read a simple bedtime story to their children.

Meanwhile the health of Americans slides.

More than 70 per cent of the population is overweight or obese.

During the pandemic, life expectancy dropped by nearly two years, from 78 to 76. It remains more than four years shorter than for most comparable rich countries.

Deaths by despair are a grim marker. In the last two decades the number of fatalities caused by suicide, drug abuse and alcohol have surged by 56 per cent to 387 per cent, depending on age cohorts (but especially among white non-Hispanic uneducated males).

Despair now kills an average of 70,000 citizens a year.

In a recent talk on America’s peril, the economic historian Niall Ferguson noted that he hasn’t seen graphs portraying such a precipitous decline in public health since the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.

The Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who first documented this epidemic of grief, wouldn’t disagree. Deaton called it a social disaster in the making:

“We see the increasing mortality and declining adult life expectancy of less-educated Americans not only as a catastrophe in its own right but also as a powerful indicator that American society is not working for the majority of its population.”

This failure, all amplified by social media, explains why the Trump revolution with its tariffs and bombast is rattling the world and reshaping Canadian politics.

Trump recognized what many of the United States’ ruling elites could not admit: that the majority of Americans no longer feel great, confident or well. His clichéd slogan “Make America Great Again” actually acknowledged uncomfortable social and economic realities.

Sandel has described the devastating results succinctly: “Three decades of market-driven globalization and technocratic liberalism have hollowed out democratic public discourse, disempowered ordinary citizens, and prompted a populist backlash that seeks to clothe the naked public square with an intolerant, vengeful nationalism.”

Harvesting discontent, however, is much easier than soothing it. Revolutions not only devour their children but engender further cycles of political abuse and violence. Trump’s alliance of oligarchs and techno-fascists is probably no more capable of fixing what is broken in the United States than the glue now securing metal panels on Elon Musk’s faulty Cybertrucks.

Given this reality, Sandel now argues that progressives must first admit their failures. More importantly they must rethink their mission and purpose.

“They should learn from the populism that has displaced them — not by replicating the xenophobia and strident nationalism, but by taking seriously the legitimate concerns with which these ugly sentiments are entangled,” he argued in 2017 and again in 2024.

That means renewing democracy with difficult conversations about the things people care about.

It means addressing the cancer of inequality with policies that actually reckon with power and wealth. “How can we reconfigure the economy to make it amenable to democratic control?” asks Sandel.

It also means addressing the hubris of educated elites and their avoidance of moral issues.

Last but not least, it means beginning a discourse about the dignity of work and redefining patriotism in an age of tyrants where borders matter once again.

Reversing the oligarchic capture of democratic institutions, adds Sandel, won’t be easy because it “depends on empowering citizens to think of themselves as participants in a shared public life.”

Thanks to the aggression of Donald Trump and his threats of annexation, Canadians have begun some of these Sandel-like conversations.

Trump’s abusive rhetoric has ironically redirected our attention from the discord feeding our own populist revolutions.

United by a bullying neighbour, Canada now has a chance to skirt the colossal political failure of the United States and not repeat its mistakes.

The Trump revolution, a shared threat to Canadian sovereignty, has given us an opportunity to redefine and renew our damaged democracy.

We won’t have another opportunity. This crisis is not a dress rehearsal.

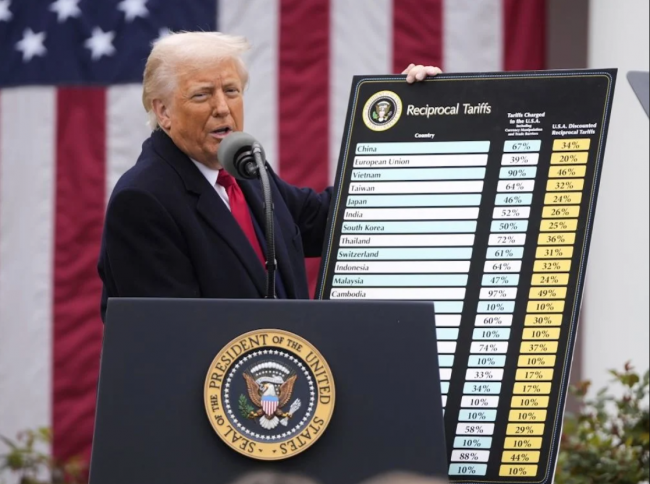

[Top photo: President Donald Trump announcing new tariffs on April 2. Most non-college-educated white men supported the radical shift. Photo by Mark Schiefelbein, the Associated Press.]