Articles Menu

Jun 24, 2022

The federal government has signalled it will be winding down British Columbia’s open-net pen salmon aquaculture industry — but conservationists worry the slow rollout could still have disastrous results on wild fish. And some say a several-year-long phase out could spell the extinction of certain Pacific salmon species.

On Wednesday federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Joyce Murray announced B.C. would transition away from open-net pen salmon aquaculture over the coming years. The government said it will publish a draft plan over the coming weeks and a final plan by spring 2023. This is on-track to meet the 2025 deadline, by which time Murray is mandated to have pulled salmon farms out of B.C.’s waters.

Industry and advocates had been waiting for news about open-net pen salmon aquaculture, as most of B.C.’s 105 open-net Atlantic salmon farm licences were set to expire June 30, 2022. On Wednesday, the government announced it had renewed licences for 79 of these farms, but had shortened licences to two years from the previous six years.

In a separate decision also announced Wednesday, DFO said it will delay making a choice about the future of 19 salmon farms in B.C.’s Discovery Islands until January 2023. DFO said it needed to consult with First Nations and licence holders after a previous DFO decision to remove salmon farms from the area was overturned in the B.C. Supreme Court this April. The Discovery Islands salmon farms will not be allowed to restock before January 2023.

Opponents of open-net salmon farms say they’re “cautiously optimistic” about the announcement, but add the government could still move in a way that benefits foreign-owned fish farm companies and hurts Pacific salmon.

The government is talking about “minimizing” interactions between farmed and wild fish, when it should be talking about eliminating those interactions, says Dan Lewis, executive director of Clayoquot Action, a Tofino-based conservation society.

“‘Minimize’ is code for in-water closed containment,” Lewis says. “The problem with that is there’s no such thing — the technology doesn’t exist.”

On-land closed containment fish farms exist and are used around the world, so that’s what the government should be focusing on, Lewis says.

An in-water closed containment system was tested by the multinational company Cermaq in Clayoquot Sound in 2019 and was reviewed by the federal government. The experiment was shut down early because of a technical fault that exposed the salmon to chronic high levels of ammonia — in other words, their own urine, Lewis says. In its 2019 review, the federal government said “floating closed containment requires two to five years of further review and offshore technologies may require five to 10 years of review.”

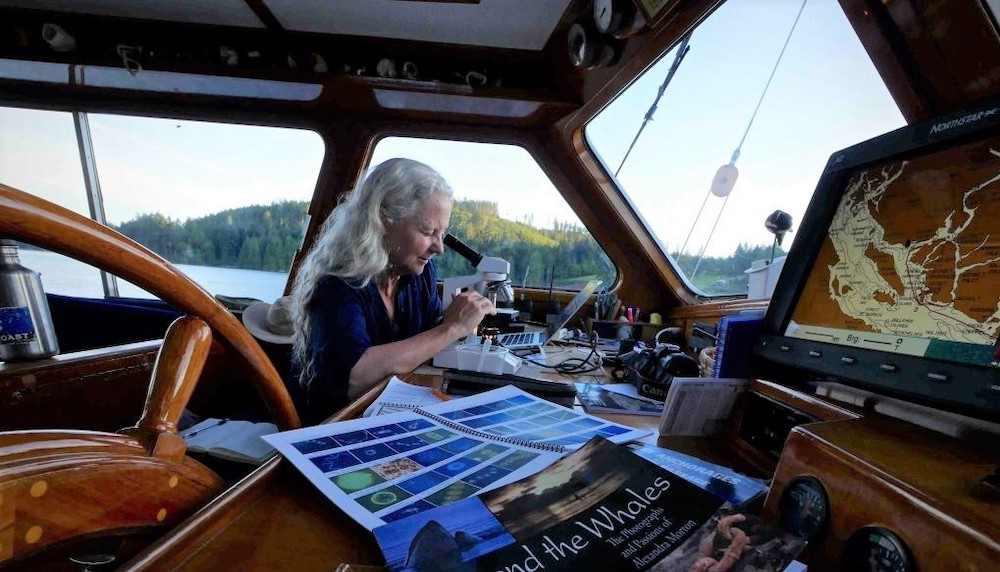

Wednesday’s decision won’t provide immediate relief for wild salmon, but issuing two-year licences for the entire coast “sends a huge message that this thing is over,” says Alexandra Morton, an independent biologist and researcher who first identified the threat posed to wild fish by sea lice infestations on farms 22 years ago.

It takes two years to grow a farmed fish, so these new licences mean companies can grow and harvest what’s currently in their pens but can’t restock, Morton says.

And while the decision is lacking some details, the government’s commitment to a slow rollout and to consultations means that it’s resilient to lawsuits, she says.

Lewis was hoping Wednesday’s decision would order all salmon farms out of B.C.’s waters — immediately.

Minister Murray has that authority under the Fisheries Act, says Margot Venton, Ecojustice program director for nature. Ecojustice is an environmental non-profit law organization.

The Fisheries Act allows the minister to take a precautionary approach when it comes to protecting wild salmon, she says. There doesn’t need to be scientific consensus on the harms caused by the farms — the minister could even say, “based on the fragility of wild salmon populations, we’re taking the farms out,” she says.

Pacific salmon populations have crashed over the last couple decades. In the late 1980s, 30 million Fraser sockeye swam up the river to spawn in a single year. The run now numbers closer to 250,000, Morton says. Rivers in the Broughton Archipelago, near the northeastern tip of Vancouver Island, that used to see 50,000 salmon now have 250 returning in a single year.

“It’s code red for wild salmon,” Lewis says.

The DFO has competing interests when it comes to wild salmon, Lewis says. On the one hand, it’s the minister’s job to protect wild fish. Parts of the ministry, like the Aquaculture Management Division, are tasked with promoting and regulating the salmon farming industry. But the ministry does not have a similar department for wild salmon. These conflicting interests have historically benefited industry over wildlife, Lewis says.

The DFO doesn’t have the greatest track record when it comes to conservation, Lewis says — after all, this is the same organization that oversaw the collapse of the Atlantic cod industry.

It’s not clear if some salmon populations will be able to recover because they’re so low, Morton adds. “They’ve become so fragile that other things can knock them out that normally wouldn’t,” she says. “We’re talking about the imminent extinction of salmon runs.”

Once they’re gone, they’re gone, she adds. Salmon have adapted over millions of years to be the perfect fish for their river. Chilko River sockeye are “long and lean and built like a bullet” and Adams River sockeye are this “gorgeous deep bodied fish,” Morton says — you can’t just drop an unfamiliar salmon in that environment and expect them to thrive.

Death by 1,000 cuts

Meanwhile, on the industry side, salmon farmers seem to be withholding judgement on Wednesday’s decision until more details are released.

The Tyee contacted Cermaq, Mowi, Grieg Seafood and Creative Salmon for comment for this story. All companies except Cermaq, who didn’t respond, declined an interview and pointed The Tyee towards the BC Salmon Farmers Association, a lobby group that advocates for fish farms in B.C., to speak on their behalf. The BCSFA was not available for an interview.

In a statement released Wednesday, the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance and BC Salmon Farmers Association said shorter licence terms reduces confidence to invest in innovation and technology, but that licence renewal is a “positive first step” towards “securing” its future in B.C.

“Salmon farms have minimal effect on wild fish abundance and farmed and wild salmon can and do co-exist in the Pacific Ocean,” the statement continues.

There’s a growing body of evidence that strongly disagrees with that statement.

Debate around how harmful fish farms are to wild fish populations is a bit similar to the debate around climate change and tobacco — the scientific community broadly accepts it’s bad, but there are disagreements about how bad it is, Lewis says.

The only people arguing that fish farms aren’t harming wild fish stocks are scientists whose research is funded by the aquaculture industry, says Sean Godwin, a postdoctoral researcher at Dalhousie University and director of the the Salmon Coast Field Station, a non-profit conservation organization in the Broughton Archipelago. Because of that, he recommends sticking to peer-reviewed science when it comes to discussions around salmon in B.C.

“It’s really hard not to sound like an advocate or activist when you’re talking on this issue,” he says. “Because the artificial debates and arguments that have been put up by industry and DFO make it seem like if you’re listening to the overwhelming scientific evidence and you weigh it accordingly and make a conclusion — then you’re an activist against salmon farming.”

Salmon are impacted by habitat loss; poor management that historically led to overfishing; climate change that impacts snow melt, changes the flow of rivers and increases the temperature of rivers and oceans; pinniped populations of seals and sea lions; and diseases and pests spread by salmon farms, Godwin says.

It’s death by 1,000 cuts, he adds.

If B.C. wants to protect salmon it needs to focus on regional goals with tangible impacts, like cancelling hatchery programs, pulling salmon farms out of the ocean and reigning in the fishing industry, he says. Some people would argue pinniped culling should also be considered, he adds.

Salmon farms spread disease and pathogens because the fish are kept in close quarters and fed and protected from predators — predators that would otherwise pick off sick or hurt fish, says Morton. This allows pathogens to thrive.

Pests like sea lice can flourish year-round in the farms. In a natural salmon migration pattern, when the adult fish returned to fresh water to spawn the sea lice would die, and the presence of sea lice in the ocean would decrease, Godwin says. But salmon farms maintain a high level of sea lice year-round which then expose the juvenile salmon as they swim by in the spring.

Sea lice are small parasites indigenous to B.C.’s oceans that attach themselves to the outside of a fish and slowly feed on its surface tissue and mucus layer. They can be extremely harmful when they attach themselves to juvenile salmon because the fish are so small.

It’s comparable to a human walking around with a leech the size of a chicken attached to them, says Don Svanvik, Hereditary Chief and Elected Chief councillor of the ’Namgis First Nation.

The aquaculture industry uses a treatment of emamectin benzoate, also known by the trade name Slice, to decrease sea lice numbers during the spring migration, but sea lice populations are becoming resistant and that will make it more difficult to control outbreaks in the future, he says.

Godwin studies the impacts sea lice have on juvenile salmon, and says there’s a strong link between the presence of fish farms and the number of sea lice on wild juvenile salmon. He says most juvenile salmon have one or two sea lice attached to them.

An infected fish will grow slower, have less success when trying to feed itself and face higher predation rates, Godwin says. The fish burns energy fighting the infection so it has less energy to grow, and will take more risks for food because it needs to keep fuelling itself to fight the infection.

Then there’s disease.

B.C. scientists were only able to recently start tracking how viruses and bacteria impact B.C. salmon — thanks to some scientific advancements that have become household names during the COVID-19 pandemic, like polymerase chain reaction tests that look at the genetic material of a virus.

These reports add to the body of evidence that suggests fish farms should be removed from B.C. waters to protect wild salmon.

One study published last month in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences found juvenile sockeye salmon fry are 13 times more likely to test positive for the bacterium Tenacibaculum maritimum when swimming past salmon farms in the Discovery Islands that are stocked with Atlantic salmon than elsewhere in the province, says Andrew Bateman, the study’s lead author and salmon health manager at the Pacific Salmon Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to the conservation and restoration of wild Pacific salmon.

The bacterium causes mouthrot disease in Atlantic salmon and can be equally devastating for other salmon species as well. Bateman’s research, which tracked where the bacterium appeared across the province, was not able to distinguish if a drop in the bacterium further down the migration route meant that infected fish had been killed, or if the new fish he was testing had successfully fought off the infection and recovered. That being said, the predicted mortality of Tenacibaculum maritimum is 88 per cent.

The second study, published last month in Facets, which Bateman was also involved in, tracked how 59 pathogens impacted Chinook and coho salmon. It found there was a statistical association between the presence of the bacterium Tenacibaculum maritimum and the virus Piscine orthoreovirus and decreased survivability of both species.

The research, Bateman says, did not set out to point fingers at the salmon farming industry, but “it’s what the data indicates. The data is why we’d say there’s a cause for concern there.”

And while Bateman says the role of the Pacific Salmon Foundation is to be neutral and provide the best scientific evidence to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, he’s now also calling for the removal of fish farms from B.C. waters.

This is a message echoed by Indigenous leaders across the province.

Hereditary Chief Tsahavkuse of the Laichwiltach Nation says fish farm companies should pack up and leave the country altogether. Tsahavkuse, whose English name is George Quocksister Jr., has a long history of advocacy against fish farms. During a partnership with Sea Shepherd Conservation Society he documented juvenile fish getting trapped in salmon pens and the animal poop that collects under the fish farms.

“It’s a poison outflow from the farms. The virus the fish have — it’s killing off all life in the coast, the prawns, fish, everything,” he says. “It’s freaking disgusting.”

’Namgis First Nation Chief Don Svanvik is working to take more of a neutral stance when it comes to the future of fish farms.

The ’Namgis First Nation sits in the Broughton Archipelago, a two-hour drive by car north from the Discovery Islands. Svanvik says since the salmon farms closed down in the Discovery Islands juvenile salmon have been swimming through this territory “plump and sassy” with next to no sea lice on them.

Sea lice researcher Godwin cautions against drawing conclusions so soon after the Discovery Islands fisheries were closed. Sea lice numbers can also be impacted by ocean temperatures, he says. Godwin is calling for a five-year study sampling many different fish at many different sites before conclusions are drawn.

To manage the health of wild salmon in their territory, the Mamalilikulla, ’Namgis and Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis First Nations formed the Broughton Aquaculture Transition Initiative, which regulates salmon farms.

BATI has already pulled 10 salmon farms out of the water. The seven farms that are left will have to, within the year, “demonstrate to us that they’re not harmful to the environment,” if they want to stay, Svanvik says. He adds he can’t elaborate on what that looks like because it’s up to the fish farms to interpret the statement.

Svanvik says B.C. has an opportunity to pull fish farms out of the water and build an on-land salmon aquaculture industry.

That’s not just talk — the ’Namgis Nation built an on-land closed containment salmon farm back in 2013 to prove it could be done. The company, called Kuterra, is now operated by Whole Oceans.

There were a few hiccups and the current size is too small to be profitable, but the team is gaining the experience it needs to scale up in the business in the coming years, Svanvik says.

The provincial and federal governments could offer loans to First Nations and municipalities to invest in similar on-land aquaculture as the open-net pen industry winds down, he says.

This idea, to pull the fish farms out of the ocean and put them on land, is echoed by many people who oppose open-net fish farms.

The global demand for seafood is rising but can’t be met through wild fisheries, so the value of aquaculture will increase, says Gary Robinson, an independent consultant for the on-land salmon industry.

On-land aquaculture allows producers to control for disease and temperature. Hundreds of fish species are grown using aquaculture around the world, though in B.C. we tend to focus on high-value species like salmon and sturgeon, he says.

Around the world aquaculture is set to take off — but B.C. is lagging behind, he says.

The province’s on-land aquaculture industry is in its infancy, but has the advantage of access to low-carbon power through BC Hydro, easy access to large U.S. markets along the West Coast and existing infrastructure that supports the current commercial salmon industry, like local feed mills, processing plants and hatcheries, he says.

But what little advantage B.C. has won’t last, Robinson says. Without clear regulations around the nascent industry, investors are likely to take their money elsewhere. It’s more expensive to run a business in B.C. than it is in Europe; infrastructure built in B.C. needs to meet seismic codes and is therefore more expensive; and B.C. is in competition with Washington, Oregon and California which are all being proactive in getting systems in place for permitting on-land aquaculture. Finally, if the open-net pen industry is closed before the on-land industry has time to establish itself — which takes years and hundreds of millions of dollars per operation — the supporting industry, with its feed mills and processing plants, will also dry up.

Salmon farm companies aren’t helping the situation.

Robinson says companies that have salmon farms in B.C. are investing in on-land aquaculture elsewhere in the world, but in B.C. they’re afraid a similar investment would signal they thought on-land farms were viable in B.C., which could then be used as an argument to close the open-net pen farms. “This is the last place they’ll invest, ever,” he adds.

Keeping open-net pens in the ocean means the sea covers a company’s environmental costs, says sea lice researcher Sean Godwin.

An on-land facility would have to pay for the facility, the land it operates on, water, water filtration, salinity management, waste management and more.

“On land you have to deal with all of that. In the ocean it just goes in the ocean,” Godwin says.

‘I’m going to find out if my whole life was a waste’

When The Tyee spoke with Alexandra Morton in early June, she said the day the DFO decision came down would be the day “I’m going to find out if my whole life was a waste.”

But on Wednesday, after the announcement, Morton said her life, which she has dedicated to researching and documenting the harms caused by the fish farm industry in B.C., hasn’t been wasted.

“It’s this wonderful, calm, warm feeling,” she says.

Maybe this is thanks to the work of First Nations and advocacy groups, or maybe enough members of the public told the government they didn’t want fish farms, but “the government finally got it,” she says.

Which is unprecedented — she couldn’t think of another time when the government chose to kick out an industry.

She hopes the government will maintain course and not cave to pressures from the aquaculture industry, because, she says, salmon are so close to extinction and really need to be able to make it to the ocean without being infected by open-net pen farms.

“Wild salmon leave the river when they’re tiny and go out into the ocean and basically collect the energy of the sun hitting the ocean,” she says. “The sun creates plankton blooms, little fish eat the plankton, and the salmon eat the little fish. Then they carry all that back and they just pour it down over the mountain — all that energy and nitrogen-15 from the ocean.”

And what happens if certain salmon populations go extinct? B.C. will lose the resident killer whales, forest growth will be reduced and food security will be threatened, Morton says. The aquaculture industry will be forced to close if fuel prices go any higher too, so it’s not a reliable backup, she says.

Losing salmon would be like “pulling the power cord out of the side of your house,” she says. “It’s gone and it doesn’t come back.”

[Top photo: The Department of Fisheries and Oceans is renewing 79 salmon farm licences, but these licences will expire in two years. That’s enough time for companies to grow the fish that are already in the pens but won’t allow them to restock, says marine biologist Alexandra Morton. Photo by Fernando Lessa.]