Articles Menu

Jan. 28, 2025

Fighting oil and gas industry developments is almost always a losing proposition. Richard Kabzems’ battle to stop a giant fracking operation on his doorstep in northeast B.C. is no exception.

Anyone doubting that the cards are stacked in the industry’s favour would do well to read a landmark judgment rendered in June 2021, by Justice Emily Burke of the B.C. Supreme Court.

Burke, ruling on an Indigenous rights issue, addressed the provincial government’s role in resource management. The industry-friendly provincial Oil and Gas Commission (now the BC Energy Regulator), she noted, had not once in its then 23-year history denied a company drilling request “because of impacts on treaty rights, habitat issues, or cumulative effects.”

So when Kabzems learned Ovintiv, a major oil and gas player in northeast B.C., wanted to drill and frack for gas and oil just over a kilometre from his house, he knew it would be tough to stop.

Kabzems lives on Lebell Road, in a subdivision halfway between Dawson Creek and Fort St. John. Ovintiv sent Kabzems and his neighbours letters in October 2022 outlining its plans. And they knew they had to fight.

Ovintiv told them it intended to clear several acres of a nearby farmer’s field of all its topsoil, prior to compacting the ground with heavy machinery and then sending rigs onto it to drill the first eight of an anticipated 24 gas wells.

Once erected, the tall drilling towers would be used to bore holes deep down into the Earth and then out horizontally for several kilometres away from the drill pad. Then more equipment would be brought in to hydraulically fracture the wells in 30 or so stages.

During each frack stage, vast quantities of water, sand and chemicals are pumped underground with incredible force to create chaos below ground. Fracking blasts the rock and creates pathways or fractures that let trapped methane gas and light oils flow so they can be pumped to the surface for capture and processing.

There are lots of issues with fracking, from massive water use to pollution to the climate impact from more fossil fuels.

But the increased risk of earthquakes is among the most alarming.

Such chaos is triggering more “felt” earthquakes of magnitude 3 or greater in the Montney basin, home to methane gas and light oil reserves. The quakes pose health and safety risks. The largest fracking-linked quake in the Montney, where Kabzems lives, has tipped the scales at magnitude 4.6.

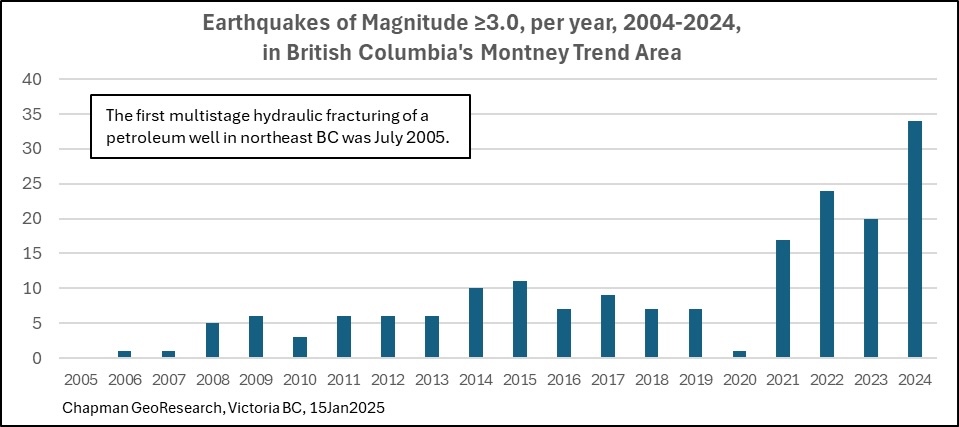

And 2024 has now entered the record books with 34 such events in the Montney, according to data recently analyzed by Allan Chapman, a former senior geoscientist with the Oil and Gas Commission.

“This is the largest number of M≥3.0 earthquakes ever recorded in British Columbia’s Montney Trend in a single year and is a concerning harbinger of the future for B.C.’s Peace River region,” Chapman warns.

It’s already happened to Kabzems

This is unwelcome news to Kabzems and his neighbours, who have already been shaken by earthquakes triggered by fracking operations not far from their homes.

In numerous reports like this one, The Tyee’s Andrew Nikiforuk has detailed how earthquakes induced by fracking have become a troubling fixture in northern B.C. and Alberta, two regions that were seismically inactive until “unconventional” fracking operations took off in 2005.

Since then, earthquakes have increased in number and magnitude, including a memorable cluster on Nov. 29, 2018.

That event involved three earthquakes in the space of 48 minutes, including one of 4.5 magnitude that was felt in households more than 100 kilometres away from each other and forced the emergency evacuation of workers at the nearby Site C dam then under construction. The quake was just 10 kilometres from Kabzems’ home on Lebell Road.

Kabzems, who vividly recalls that quake and its powerful aftershocks, says it is an experience you don’t forget. “It’s sort of like having a large diesel truck ram into the side of your house,” he told The Tyee. “You feel this very low rumbling and then things start to move around.”

The prospect of such an earthquake — or worse — triggered at a well site in his backyard is one of many reasons why Kabzems and others objected to the Ovintiv project.

In an April letter last year to the BC Energy Regulator, or BCER, Kabzems noted how in recent years China’s Sichuan region has been rocked by earthquakes triggered by fracking.

The quakes have killed two people, injured many more, badly damaged hundreds of houses, causing many to collapse, and triggered landslides.

“The best science indicates that earthquake events exceeding M5.0 are possible for our homes,” Kabzems wrote, adding such events will increase “in direct relation to the number of hydraulic fracking wells and water volume injected each year.”

He went on to note that the regulator “has no control over either the timing or magnitude of earthquakes induced by hydraulic fracturing after permits are granted” and that because of that it should deny Ovintiv’s application.

“If a home is structurally damaged by seismic events... will BCER provide compensation?” Kabzems went on to ask in a letter sent to Dane Eggleston, a landowner liaison with the regulator.

For Kabzems this is no trivial matter. His home insurer has informed him that in the event his house is damaged by an induced earthquake, there will be no coverage.

Neither Eggleston nor any other employee with the regulator responded directly to that question or others Kabzems put to them.

Instead, on July 8, Sean Curry, the BCER’s vice-president responsible for development and stewardship, signed a nine-page permit granting Ovintiv its request to build the well pad and drill and frack up to 24 wells. The permit makes no mention of earthquakes.

Kabzems has now learned that the drilling is set to commence on Feb. 9.

Priming the pump

In 2021, research by Chapman was published in a peer-reviewed paper in the Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection. Chapman found that the cumulative effect of multiple fracking operations over time primes the pump for increased numbers of earthquakes and potentially stronger, more destructive seismic events.

As one example, Chapman looked at the cluster of earthquakes in November 2018. For days prior, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., or CNRL, was fracking at a well site roughly 20 kilometres from the Site C dam when the trio of earthquakes occurred.

During those days, CNRL pressure-pumped the equivalent of nearly six Olympic swimming pools of water underground as it fracked the site, which was later identified as the proximate cause of the earthquakes.

Chapman’s research also showed something else. Over the three years prior to November 2018, Ovintiv, ARC Resources, Crew Energy and CNRL between them blasted the equivalent of 688 Olympic swimming pools of water underground in fracking operations close to where the large earthquakes occurred. The extra water that CNRL then added to the mix may have been all that was needed to tip the scale causing the cluster of quakes, “the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back,” Chapman said.

“Fracking-induced earthquakes in the Montney and elsewhere will continue to be a pervasive issue with ongoing public safety, infrastructure and environmental risks,” Chapman stated near the end of his paper.

As fracking activities accelerate later this year to provide large quantities of methane gas for processing and export at the massive LNG Canada facility now close to completion in Kitimat, “both the frequency of earthquakes and the magnitude of earthquakes are anticipated to rise,” he added.

Earthquakes all over

When contacted by Kabzems, Chapman volunteered to analyze just how many earthquakes have occurred in recent years near the Lebell Road subdivision.

Using data from Natural Resources Canada’s national earthquake database as well as data from the BC Energy Regulator on the location of fracked gas wells, Chapman plotted just how many earthquakes had occurred in the region from 2013 to 2023.

Analyzing the two information sources, Chapman found that 279 wells had been drilled and fracked within six kilometres of the subdivision during that time frame.

Those operations pumped the equivalent of 2,050 Olympic swimming pools of water into the earth, during which time 73 earthquakes were reported within the six-kilometre zone, meaning roughly one earthquake for every four wells fracked.

Chapman also looked at events in a wider 12-kilometre radius of Lebell Road and found that 739 wells were fracked, 4,702 Olympic swimming pools’ worth of water was pumped and 177 earthquakes occurred, again for an average of roughly one earthquake per four wells fracked.

Such frequencies are in keeping with a peer-reviewed study in 2016 led by respected seismic expert, geologist and professor emeritus at Western University Gail Atkinson.

Strong ground motions

In the journal Seismological Research Letters, Atkinson and the report’s other co-authors noted that in Western Canada induced earthquakes are “highly correlated in time and space with hydraulic fracturing.”

Such induced earthquakes have heightened potential to be destructive, Atkinson says, because the depths at which they occur are typically closer to the earth’s surface than naturally occurring earthquakes.

The “strong ground motions” associated with near-surface earthquakes behave differently than those triggered by deeper earthquakes and thus pose potentially greater risks to nearby infrastructure such as hydroelectric dams, which have been a focus of Atkinson’s work.

To protect such infrastructure from induced earthquakes, Atkinson has advocated for no-fracking buffer zones around critical infrastructure and special management zones ringing those buffers to reduce the risk of induced earthquakes causing damage.

The risks also increase based on the nature of the subsurface in different areas.

In a 2020 study published by Geoscience BC, researchers found that there is a risk of “high amplification” of ground motions triggered by earthquakes in geological zones with stiff soils, conditions that prevail in the Lebell Road area.

The report further notes this geological feature is “widespread” in the Montney region.

Recently, other published studies have underscored the risks that induced earthquakes could pose to Kabzems and his Lebell Road neighbours.

A large thrust event

In a 2024 master’s thesis, Chet Goerzen of the University of Victoria used a dense array of seismometers to study induced earthquakes at an Ovintiv well pad about one kilometre north of Lebell Road.

Goerzen’s thesis was supervised by Honn Kao, a lead scientist at the Geological Survey of Canada’s Pacific region offices in Sidney, B.C., who is investigating induced earthquakes. Kao also heads the office’s seismology, tectonophysics and volcanology department.

Goerzen’s successfully defended thesis found that in the area immediately north of Kabzems’ home, below-ground fractures in the rock were “seismogenic,” meaning they were capable of generating earthquakes that could be triggered by fracking.

Should such earthquakes occur, they could be magnitude 3 or greater and have the potential to “cause damage to the infrastructure nearby, and would likely be felt by residents in the immediate neighbourhood,” he concluded.

Goerzen’s study also identified something else — “a large-scale lineament” below ground just three kilometres northwest of Kabzems’ home. A lineament indicates a possible fault line. If there is a fault, “it would be well oriented for a large thrust event,” Goerzen reported.

That could result in “an induced earthquake of magnitude of 5.5 to 6.1.”

The U.S. Geological Survey’s earthquake calculator shows that earthquakes of magnitude 5.5 and 6.1 would respectively be eight times and 32 times bigger than the strongest fracking-induced earthquake to occur in northeast B.C. in 2018.

Trains, trucks, cows and thumps

The 2020 Geoscience BC study looked at possible earthquake impacts on people living in the Montney region.

“A common experience is hearing a loud thump or rumbling, like a train, truck or cow coming through the house, loud enough to wake people at night. Others describe rattling of windows and dishes,” the report’s authors note. “The differences in experiences may correlate with differences in geological and topographical setting. Some residents report several events in a single day during ongoing hydraulic fracturing operations.”

Chapman says current regulations governing the fracking industry’s required consultations with landowners are “grossly inadequate.”

If Ovintiv had located its well pad and fracking base just a bit farther away from Lebell Road, Kabzems and his neighbours would not have even been informed of the company’s plans.

As a case in point, Chapman reported to Kabzems that there are 141 wells approved for drilling and fracking within five kilometres of Kabzems’ home, but far enough away that he and his neighbours would not even have been notified that fracking permits had been issued.

Under current provincial regulations, companies proposing gas wells must consult with people who live within 1.3 kilometres and notify all landowners living up to 1.8 kilometres away.

But in a recent report, David Hughes, an Earth scientist who has studied the energy resources of Canada and the United States for more than 40 years, noted the average length of the horizontal well bores currently being fracked in the Montney now approaches three kilometres, considerably beyond the BCER’s consultation and notification thresholds.

Under current regulations companies are also required to respond to issues raised by affected landowners, pass on any correspondence to the regulator and inform landowners that they can write directly to the regulator with their concerns prior to the regulator making a decision.

In addition, landowners with consultation rights can object to a decision made by the regulator, should they believe that concerns they raised were not adequately addressed.

‘Simply the wrong place’

In Kabzems’ view, common sense would dictate no drilling and fracking so close to a subdivision. What, he wonders, would Premier David Eby or Energy Minister Adrian Dix think about earthquake-inducing wells being drilled and fracked in their backyards?

The Lebell Road subdivision is unusual for northeast B.C. Typically, rural residences are spread out and on larger acreages. But in Lebell’s development, houses were located much closer together on pie-shaped lots with large expanses of land held in common as wooded estate or cleared parkland, including space for an outdoor ice rink in winter and baseball diamond for use in warmer months.

There are 33 residences on Lebell Road and another 18 residences nearby.

This gives the neighbourhood a higher concentration of people, which Kabzems pointed out to Scott Porter, a senior land negotiator with Ovintiv, in a letter last February.

“This is an exceptional situation in the B.C. Peace River area for any proposed hydraulic fracking gas development,” Kabzems wrote, adding that “this is simply the wrong place to put a multiwell padsite.”

In a subsequent letter to Porter, Kabzems noted that two Ovintiv geophysicists who attended a public meeting at the nearby Tower Lake community hall last March did not know that local residents wanted answers about who would bear responsibility in the event of a damaging fracking-induced earthquake.

“The two... were not aware that earthquake insurance coverage is not available for my home, or to other residences within two kilometres or less of the proposed well site. Their response was that Ovintiv employees would need to discuss this question, which was new information for them,” Kabzems wrote, adding that he wanted to know what Ovintiv’s position was on compensation.

“Will Ovintiv take financial responsibility for repair of the structural damage to homes when Ovintiv fracking at the proposed location creates an induced seismic event?” Kabzems asked.

The company has yet to answer that question, he said.

‘Remarkably sparse’

Kabzems also said he and others were worried about the risks posed to their health from so many gas wells nearby, citing a recent peer-reviewed report in the Canadian Journal of Public Health. It drew on 52 studies from nine jurisdictions where fracked oil and gas developments, also known as unconventional developments, occur.

The report identified adverse health outcomes linked to unconventional oil and gas development including low birth weights, premature births and birth defects, respiratory problems including asthma, increased incidence of cardiovascular problems and incidence of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Led by environmental epidemiologist Amira Aker, the report concluded that there is a “growing body of research” linking adverse health outcomes to unconventional oil and gas operations.

Despite this, Canadian research on such adverse health outcomes is “remarkably sparse.”

“There is a pressing need for additional evidence,” the scientists concluded.

No position on liability

The Tyee emailed several written questions to the BC Energy Regulator, including questions on liability if fracking operations approved by the regulator triggered damaging earthquakes.

“The existing regulatory framework is designed to ensure the secure and safe operation of wells and facilities to protect public safety and the environment,” the BCER said, adding that “oil and gas operators are responsible for the safe operation of their activities within this framework.”

The BCER went on to note that a special set of rules governing induced earthquakes applies in the Kiskatinaw region, so named for the river of the same name that lies a short distance from Kabzems’ home.

In the Kiskatinaw Seismic Monitoring and Mitigation Area, oil and gas companies are required to report any earthquake of a magnitude of 1.5 or greater to the regulator and to halt any fracking operation in the event a magnitude 3 or greater earthquake is triggered.

This is described by the fracking industry and regulator as a “traffic light protocol.” Smaller magnitude earthquakes trigger a yellow light, requiring reporting, and bigger earthquakes trigger a red light, leading to a temporary halt to fracking operations at a specific well site.

Notably, the monitoring and mitigation area represents just nine per cent of the area where fracking is occurring in the Montney. For the remaining 91 per cent, where induced earthquakes regularly occur, the regulator has no specific protocols in place to attempt to prevent large magnitude earthquakes from occurring.

In its written responses the BCER said the fracking industry and regulator typically observe “smaller magnitude events [earthquakes] in a fault corridor than we do larger events. In practice, this means there is a higher probability we’ll observe a smaller event prior to recording a larger event.”

“This is the premise of all Traffic Light Protocols,” the BCER continued. “The probability of smaller events occurring prior to larger events provides a permit holder the opportunity to make operational changes to avoid larger seismic events along a fault corridor that is critically stressed.”

But should such protocols fail to prevent a damaging earthquake from occurring near Kabzems’ home, the provincial regulator said it had no answer on the issue of who would bear responsibility.

“The BCER cannot speak to its position on questions of liability,” the regulator told The Tyee.

Yet on other matters pertaining to oil and gas industry operations, the provincial fracking regulator clearly does have issues of liability in mind.

For example, the permit issued to Ovintiv allowing it to drill near Kabzems’ home requires the company to have insurance of $1 million to protect the regulator, the province and permit holders from claims of personal injury, death, property damage or third-party liability claims arising from any accident or occurrence on roads near their facilities.

The fracking paradox

In his 2021 publication, Chapman noted that traffic light protocols like those in place for the Kiskatinaw region are not foolproof.

Many large magnitude earthquakes induced by fracking occur without smaller precursors. Notably, the regulator’s traffic light system failed to prevent the large magnitude 4.5 and 4.2 earthquakes that occurred in November 2018, just 10 kilometres from Lebell Road.

Complicating matters, earthquakes may occur after fracking operations have ceased.

A recent study led by Ryan Schultz, a geophysicist at Stanford University, found that there were time lags of up to two days following fracking before earthquakes occurred in the north Montney region, where Progress Energy, a subsidiary of the Malaysian state-owned company Petronas, was identified as having set off a 4.6 magnitude earthquake during a fracking operation at one of its well pads in 2015.

Petronas is slated to be a major supplier of methane gas to the LNG Canada facility and will be among the top companies fracking in northeast B.C. for years to come.

The more water pumped during fracking, the more likely earthquakes are, Schultz and his colleagues reported, adding that the number of earthquakes scales “linearly” with the amount of water pumped.

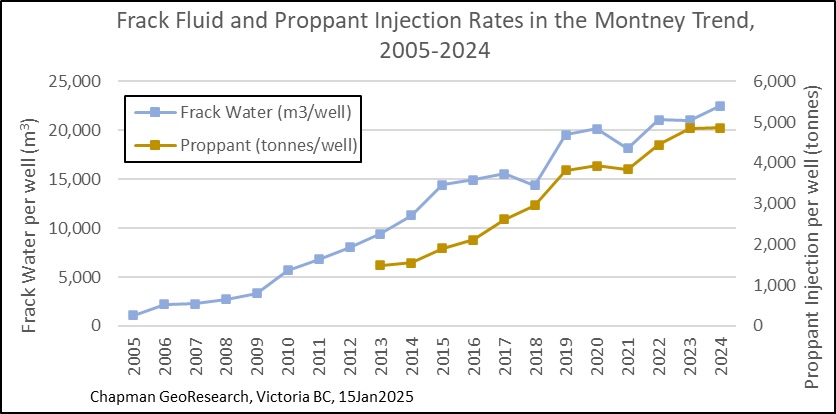

Adding weight to that finding is Hughes’ recent analysis, which found that the fracking industry’s water use in the B.C. and Alberta portions of the Montney has skyrocketed with water-pumping at fracked wells now averaging 23.1 million litres or nine Olympic swimming pools, for “a 10-fold increase since 2010.”

But perhaps the greatest obstacle to trying to effectively regulate an end to potentially damaging and life-ending earthquakes is a paradox noted by Schultz and company.

“Unfortunately,” they report, “it would seem that fluid injection (coupled with monitoring of earthquakes) is one of the best techniques for locating seismogenic faults.”

In other words, it’s by fracking that you learn where the faults are and where earthquakes might occur. And such earthquakes might not happen until after the fracking has stopped.

With land clearing well advanced at the Ovintiv well pad, Kabzems has engaged a lawyer to try to fight the approval before the Energy Resource Appeal Tribunal, which hears complaints brought by landowners. But he is not holding his breath that anything will change.

The request for an appeal was filed in the middle of August, and five months later Kabzems has yet to even be informed as to when the appeal will be heard.

Meanwhile, he and his neighbours continue to do lonely battle in a remote region that is being steadily drained of its resources while out of sight and out of mind of those living in the populous southwestern corner and political base of the province.

And the draining is poised to go into overdrive later this year as the LNG Canada facility begins liquefying methane gas and pumping it into the cavernous holds of ocean tankers for export to Asia, at which point Kabzems and all residents living in B.C.’s Peace River region are slated to experience an explosion in drilling and fracking operations.

None of this, Kabzems believes, would be tolerated for a moment in the populous southwest corner of the province.

“If a major industrial development like this... was going to repeatedly through its construction life and operational life disturb the existence of 50-plus residences in a rural area of Surrey, there would be public discussion,” Kabzems told The Tyee.

“And government might be forced to act.”

[Top photo: Richard Kabzems and Sandra Burton stand outside their home a short distance from a gas well pad where they fear fracking operations could trigger damaging and potentially deadly earthquakes. Photo by The Tyee.]