Articles Menu

Sept. 26, 2025

After three years of drought, the City of Dawson Creek has reached a dangerous tipping point as the Kiskatinaw River, its only drinking water source, falls to levels never before seen.

With its climate-change-fuelled drought showing no sign of ceasing, the city has asked B.C.’s Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness to see the unfolding situation for what it is — an emergency — and step in with support.

A temporary fix would be to pump water out of the Peace River, more than 50 kilometres away, through a network of linked, pressurized, industrial hoses while the city awaits word from B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office on a proposal to lay a 36-inch water pipeline and pumps along the same route from roughly the community of Taylor to Dawson Creek.

If the city’s plan is approved, that pipeline would convey up to 10 million cubic metres of water per year from the region’s largest and heavily dammed river, an amount three times greater than what the city of approximately 12,000 residents currently uses.

To help offset its costs, the city would then be able to sell potentially millions of cubic metres of water to the very industry that has contributed most heavily to the climate crisis: oil and gas. Oil and gas companies are currently guzzling more water in northern B.C. and Alberta than at any point in history as they drill and frack for methane gas and light oils and exports of liquefied natural gas from Canada’s first gas export terminal in Kitimat begin to soar.

The request for emergency relief comes as the city starts drawing down its water reserves for the second time in under two years.

‘A desperate situation’

Kevin Henderson, Dawson Creek’s chief administrative officer, told The Tyee in an in-person interview that between the last week in August and the first week in September the already parched Kiskatinaw River lost a further 40 per cent of its flow.

“If we aren’t able to pump out of the Kiskatinaw River, we have about 150 days of water [in our reserves] — October, November, December, January, February,” Henderson said during an interview in his office on a bright and once again dry day in early September.

“We’re going to be in a desperate situation. I believe we’re going to have to have supplemental water. If we have no water and the ground freezes in October/November, that moisture that does fall as snow will not help us until the spring,” Henderson said.

A short distance away, motorists on the Alaska Highway passed a sign illuminated with green LED lettering reminding them that Stage 2 water conservation measures are in effect.

The Tyee received emailed responses to questions from a number of provincial offices, including the Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness, or EMCR, that acknowledged that Dawson Creek’s precarious water situation is a matter of ongoing discussions.

“Planning is underway between the City and EMCR to prepare for possible emergency response measures should drought conditions persist into the fall, which could include declaring a State of Local Emergency. EMCR will review any requests and costs for emergency response measures once they have been submitted,” the ministry’s communications department said, adding that in a “drought emergency” the province “may reimburse First Nations and local governments for eligible drought response activities such as transportation [of] water for drinking.”

The city’s water worries first came to light in August when CBC News reported that Dawson Creek had asked the Environmental Assessment Office, or EAO, to fast-track a proposal that would allow the city to draw 10 million cubic metres of water per year from the Peace River.

If the proposal is approved, the city would tender contracts to install the pipe and several pumps along the pipeline route at an estimated cost of $100 million.

Allan Chapman, who worked in several professional capacities as a hydrologist in various provincial ministries as well as for the provincial River Forecast Centre and B.C.’s Oil and Gas Commission, told The Tyee that what has unfolded on the Kiskatinaw is of deep concern.

‘Zero measurable flow’

“Unless the weather in the Kiskatinaw becomes rainy over the next month, the winter of 2025-26 appears destined to experience the lowest winter discharge of record, with an extended period of zero measurable flow,” Chapman told The Tyee.

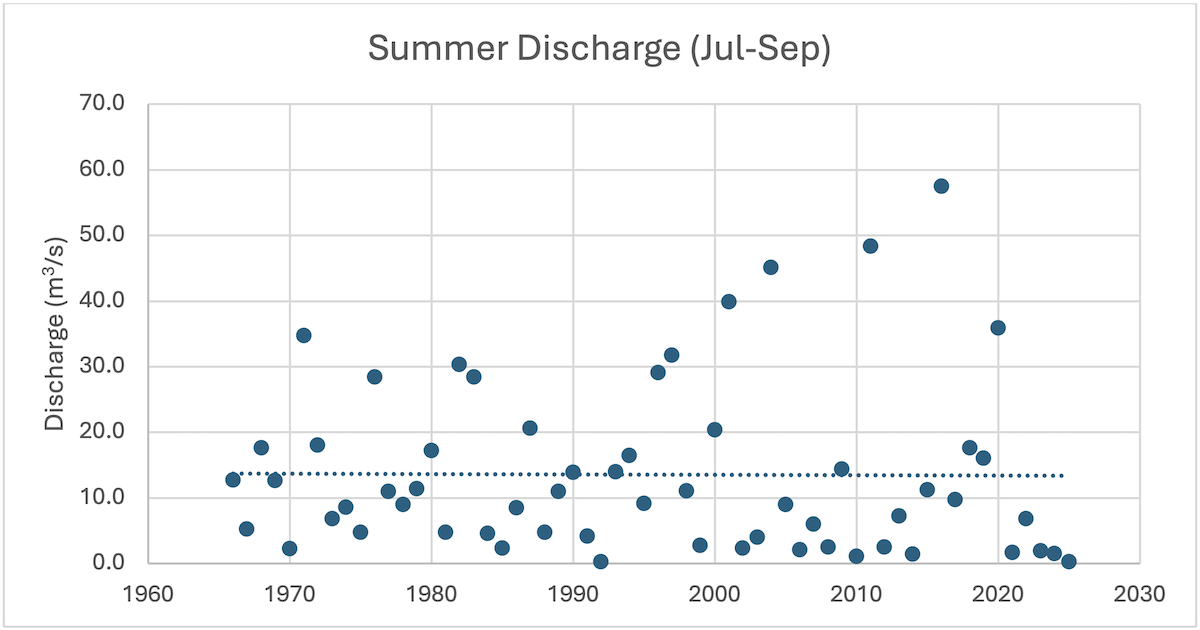

Chapman based his projection on an analysis of nearly 60 years of continuous hydrometric data collected on the Kiskatinaw at a point just downstream from where Dawson Creek draws its water.

“Three consecutive winters of record-low discharge is extraordinary, with greater than a 200-year return period,” Chapman added. “There are profound implications for the survival of fish and other aquatic organisms in the Kiskatinaw River (and likely other rivers in the area, such as the Pouce Coupé); and there are profound implications for the City of Dawson Creek’s water supply for the upcoming winter.”

In addition to the Kiskatinaw being a critical drinking water source, the river is home to bull trout, a fish species that has been “blue-listed” by the provincial government, meaning it is of special concern given plummeting numbers throughout its range. The fate of the long-lived fish was dealt a significant blow in the wider Peace region by the construction of the Site C dam and subsequent flooding of a major portion of the Peace River valley last fall, which cut off access to important habitat for bull trout including the lower and upper reaches of the Halfway River.

Dawson Creek’s application to the EAO, if approved, would give the city access to a volume of water three times greater than what its residents and businesses currently use. The city has told the EAO that the water not used by the city could then be sold “as a reliable source of fresh water to rural residential, agricultural and industrial water users via truck fill stations along the pipeline route and direct pipe connections where practical.”

The fracking industry’s growing thirst

By far, the most consequential industrial user of water in the Dawson Creek area is the fracking industry, which has a history of flouting environmental, water and dam safety regulations in its race to secure water.

The most egregious of those violations involved building nearly 100 unauthorized dams that altered the region’s hydrology and form part of a wider industrial footprint that includes an even greater number of dugouts.

Dugouts are essentially large excavated holes in the ground designed to capture groundwater and surface water — water that otherwise might have flowed into rivers like the Kiskatinaw.

According to a report submitted to the provincial Ministry of Forests in 2017 by Jim Mattison, formerly B.C.’s water comptroller, the number of large and very large dugouts in the Peace region numbered 230 that year, with the majority associated directly with fracking operations.

In 2021, Chapman published a peer-reviewed research paper in the Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection noting how between just 2012 and 2019 the average volume of water used to complete fracking operations in the Montney basin, which underlies the Dawson Creek area and is set to be the primary source of LNG exports from Canada, more than tripled to 22,000 cubic metres from 7,000 cubic metres per well.

But this was an average. There were a number of instances where companies used considerably more water. In the most extreme of those cases, ConocoPhillips used an average of 83,000 cubic metres of water at each of 13 gas wells it fracked in 2019.

For perspective, an Olympic swimming pool holds 2,500 cubic metres of water, meaning that at the average Montney well in 2019 the water pumped below ground with earthquake-inducing intensity was equivalent to nine Olympic swimming pools, while the outlier ConocoPhillips pumped an average of the equivalent of 33 Olympic swimming pools.

More recently, energy analyst David Hughes calculated that the demand for water by fracking companies operating in the Montney basin is set to skyrocket.

In 2024, as reported by The Tyee’s Andrew Nikiforuk, a report written by Hughes concluded that oil and gas companies operating in the Montney were using on average 10 times more water per fracked well than they did 20 years ago.

That water use is poised to increase by as much as another 61 per cent as B.C.’s LNG exports climb.

Eyes to the sky

Henderson, Dawson Creek’s chief administrative officer, has lived almost all of his life in the area, growing up on the family farm in the nearby rural enclave of Rolla. As a boy, he said, he came to see the world as farming families do — with an eye to the sky.

“We were raised to be in tune with the weather,” he said. “But I do not recall going through a drought like this in my lifetime, and I’m 55.”

He went on to say that one of the more troubling signs of a region undergoing rapid climate change is the growing number of frost-free days. A handful of years ago those days numbered 75. “Now,” Henderson said, “it’s well over 120.”

The rapidity with which the region has warmed and dried is particularly problematic for rivers like the Kiskatinaw that receive no water from melting glaciers or high snowpacks from surrounding mountains.

“This river is so reliant on surface runoff. Without snowpacks or spring, summer or fall rains, this is the result,” Henderson said. “The river is very reliant on wetlands to feed it, and a number of wetlands that are dry, not wet, are the batteries for this system. It is going to take a lot of time and a lot of moisture to replenish that battery.”

Henderson said that the projected $100-million cost of the pipeline is hefty for a community of Dawson Creek’s size and that the excess water can be sold to offset those costs.

“Will there be water available for industry? Yes. We need to look at how we can possibly fund this project. No. 2, we think it will bring accountability to that water use. Whereas right now, companies may be diverting water and I don’t know whether there is that rigour and accountability there,” Henderson said.

Just steps from Henderson’s office, a mixed-medium artwork of a sculpted man lowering a bucket into a water well graces a wall at the foot of a flight of stairs leading down to a foyer at the main entrance to Dawson Creek’s municipal hall.

One flight down stands another piece of art, a sculpture donated by a local company servicing the oilpatch. Two oil riggers stand on either side of a pipe descending down into the earth at a methane gas or oil well — a reminder both of the central economic importance of the energy industry in the Peace region and what could soon be burgeoning tensions over increasingly scarce water resources as droughts wreak havoc on rivers like the Kiskatinaw.

In response to questions from The Tyee, the EAO said it had started its review of Dawson Creek’s application, which includes a request that the proposed project be exempt from a full environmental assessment, on Sept. 3.

The EAO added that the initial “early engagement process” with First Nations, unspecified “stakeholders,” technical experts and members of the public is expected to last 90 days, after which a decision could be made quickly.

“The EAO appreciates the urgency of the situation, and is working closely with [the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship] to ensure a timely and transparent review process,” the EAO said.

In response to other questions, the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship stated that it has not yet received an application from Dawson Creek for a short-term water use permit, which would confer water rights for a period of up to two years, or for a longer-term water licence.

If Dawson Creek applies for and is granted a water licence “with a waterworks purpose,” the ministry continued, the licence would “allow the city to provide water to a multitude of end users.” The ministry might then require that the city provide reports on how much water was used and to what purposes it was put.

Water used in fracking lost to the hydrological cycle

The environmental organization Stand.earth has been focused on water use by the fracking industry for some time and will soon release a report on the industry’s rapidly increasing use of water in the drought-stricken Peace region.

Sven Biggs, Stand.earth’s Canadian oil and gas campaign director, was recently in the Peace region and told The Tyee he came back humbled by what he saw.

“I hiked down to the Kiskatinaw and it was shocking. It was extremely low,” Biggs said, adding “it’s not just Dawson, it’s the entire region that’s facing difficult decisions around water.”

Biggs noted the news in early June in Tumbler Ridge, a community a little over an hour’s drive to the south of Dawson Creek, where local residents were ordered to drastically reduce their water consumption after local firefighters drew down the community’s water supply significantly to fight an apartment fire.

Biggs said it is important to distinguish between the water used in fracking operations and the water used by municipalities and most other industries.

When cities and many industries use water, the wastewater generated is treated and often released back into the environment, where it becomes part of the water cycle.

In fracking, the water is rendered so toxic with salts, chemicals and even radioactive elements that the industry’s only “treatment” at present is to pump it underground for permanent storage. In other words, it’s lost to the hydrological cycle forever.

Biggs said the current drought underscores a pressing need to fully understand how the fracking industry’s extensive water use and its water impoundment structures may be altering the hydrology in drought-stressed watersheds like the Kiskatinaw and in the wider region, where conditions continue to become drier and drier to the point where vast swaths of it are burning in wildfires.

“There clearly hasn’t been near enough studies, and the studies that have been done have been scattershot,” Biggs said.

With fracking operations “ramping up so quickly now, science is needed at this critical juncture more than ever,” he added.

[Top photo: A section of the Kiskatinaw River running dry just upstream of the old Highway 97 trestle bridge between Fort St. John and Dawson Creek. Photo for The Tyee by Don Hoffmann.]