Articles Menu

In the 1960s, Vancouver’s historic downtown was at risk of being razed for modern road projects – only for an extraordinary protest movement to turn the tide, helping transform it into one of North America’s most ‘liveable’ cities.

Half a century on, Shirley Chan can still picture the freeway that would have destroyed her old neighbourhood. “Three storeys high; eight or 10 lanes of traffic … you can imagine the dead zone along here,” she says, indicating with a sweep of her arm the swathe it would have cut through Chinatown and across Vancouver’s historic downtown east side.

In the 1960s, Chinatown was a vibrant, messy place. The sidewalks spilled over with fishmongers and fruit sellers. There were mom-and-pop grocery stores, benevolent societies, dim sum places, gambling parlours – even the alleyways had restaurants.

“The isolation would’ve slowly killed all of it. And not just here. Strathcona would be gone, Gastown too. We had no choice but to fight,” Chan says.

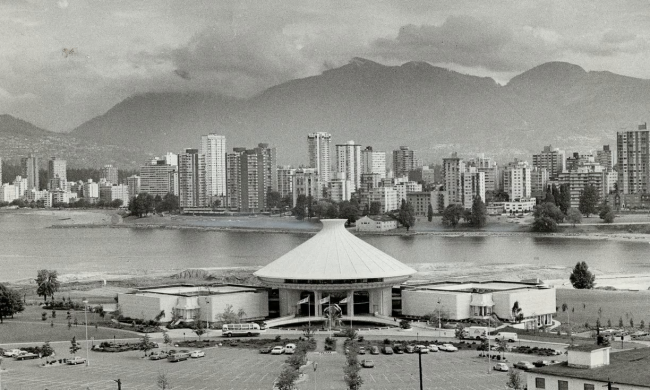

Announced in 1967, the freeway was part of a larger urban renewal scheme to modernise Vancouver’s road network and revitalise its then-struggling inner city. Had it gone through, the scheme would have razed vital neighbourhoods and built massive elevated roadways with an LA-style cloverleaf interchange.

Such a plan seems unthinkable today. Known for its embrace of public space and pedestrian- and bike-friendly planning, Vancouver is the only major North American centre without an inner-city freeway. Gastown and Chinatown together form the cultural heart of the postcard-beautiful downtown peninsula.

The city grew quickly after the second world war, and by the mid-60s the population approached one million. As car ownership spiked, people and businesses started to move out of the centre. The downtown business district began to stagnate, and the inner-city neighbourhoods, already dense and poor, continued their decline. Fast, direct arterial roads that would link downtown to the burgeoning suburbs, and link Greater Vancouver to the Trans-Canada Highway – then under construction – seemed like the obvious solution.

Large-scale redevelopment was packaged with the freeways as an opportunity for a blank slate. “The thinking at the city was, tear down the blight areas and replace them with new, cleaner, better housing for the poor, and you increase access for the middle classes too,” says Gordon Price, director of Simon Fraser University’s city programme.

The process had begun in the early 60s. Parts of Strathcona, a working class immigrant enclave, were bulldozed to build a public housing project. Nearly a thousand residents, about a third of the population, were relocated. Shirley Chan’s mother, Mary Lee Chan, organised some of the first protests. “As a kid, I remember going door to door as a translator for my mother, handing out flyers, hosting meetings at our house,” Chan says.

Following the announcement, hundreds of people marched through Chinatown, singing protest songs and brandishing anti-freeway signs.

“The Chinese community was well-represented. My mother and Harry Com [another organiser] made sure of that. But there were people from across the city. Academics, architects, students, teamsters, business people. Everyone had their different reasons,” Chan says. By then she was a university student and a community organiser in her own right.

City Hall, led by mayor Tom Campbell and chief planner Gordon Sutton-Brown, both establishment stalwarts, took a dim view of the opposition. The protesters were dismissed as left-wing malcontents: “Maoists, communists, pinkos, left-wingers and hamburgers,” in Campbell’s memorable, if slightly puzzling, formulation later on. At the same time, there was anxiety within the city because it had not yet secured extra funding needed from the federal and provincial governments for the project to go ahead.

Video: Freeway protests in Vancouver in the 1960s

City Hall grudgingly held public consultations while organisers within the protest movement made a point of demonstrating the breadth of the growing coalition. “We used subtle tactics, [for example] bussing in senior citizens from Chinatown so they could be heard,” says former British Columbia premier Mike Harcourt, who cut his teeth as the movement’s unofficial legal council.

The early leadership of Walter Hardwick, a respected urban geographer, and the support of Peter Oberlander, the Town Planning Commission chair who retired his post in protest at the plan, loaned credibility to the anti-freeway movement, as did that of forward-thinking business leader Art Philips.

Oberlander wasn’t the only ally within the municipal government. Darlene Marzari, a social planner with the city at the time, used her position to sabotage the effort to win over Strathcona residents. “My job was to relocate hundreds of Chinese families, to convince them the plan was okay. Instead I helped convince them to organise against us,” she says.

City council meetings now regularly overflowed with hundreds of concerned citizens. The Chinatown Freeway Debates, as the raucous, often confrontational sessions came to be known, continued for the rest of the year.

The first major blow to the freeway plan came in November 1967. The city was lobbying the federal minister for transport and housing, Paul Hellyer, for his support. A tour of the “blight” areas of downtown was arranged to help him understand the need for the project. Marzari and Chan managed to infiltrate the tour.

As they drove around, Chan, seated next to the minister, offered a steady counter-narrative: “The city people said, ‘Look at the sagging roofs of the houses,’ and I said [to Hellyer], ‘Yes, but look at the structures. They’re good.’ I told him the community had not been consulted, we were not happy about being moved from our homes. The people who had already been moved felt totally cut off.”

That same day, Hellyer announced a nationwide freeze on federal funding for urban renewal. It was an early victory for the anti-freeway movement in what would be a six-year battle.

Along the way, the movement become more ambitious in its goals. The focus shifted from merely stopping the expropriation of inner-city neighbourhoods to challenging its very approach to planning.

The dirty secret is that the freeway would’ve gone ahead if the money had been there

Gordon Price

“The city simply looked south of the border and adopted what Americans did, 10 years later. There was no critical thinking, no consultation,” says Dr V Setty Pendakur, professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia’s School of Community and Regional Planning, and a former activist. “You only needed to drive to Seattle to see how freeways choked the life out of neighbourhoods.”

Drawing on the experiences of local residents and the input of experts like Hardwick and Oberliner, the movement coalesced around the idea that neighbourhoods should be at the heart of city planning. The Electors’ Action Movement (Team) was formed to contest the municipal elections. They won two seats on city council in 1968 – a moral victory but not enough to change the way things were done at City Hall.

The city continued to push the freeway plan, revising the proposal several times over the next few years without ever seriously addressing the movement’s larger concerns. During this time, the Dunsmuir and Georgia viaducts, twin 800m stretches of elevated roadway, were built on the edge of Chinatown, with the idea that they would eventually connect to the freeway in whatever form it finally took. Still, federal funding was not forthcoming.

“The protests were important,” Price says, “but the dirty secret is that the freeway would’ve gone ahead if the money had been there.”

By then, anti-freeway sentiment was widespread in Vancouver and across Canada — Toronto was fighting its own battle, against the proposed Spadina Expressway. Team swept to power a few months later, winning a majority of seats on city council. Philips was elected mayor. Harcourt, Marzari and Pendakur also found themselves moving from the front lines to council chambers.

“The first thing we did was fire the planning department and let the freeway project die,” Harcourt says. It was a turning point in Vancouver’s history.

Team ushered in a number of reforms and initiatives. For a few heady years in the 70s, planning was radically consultative, centred around the city’s 20 or so neighbourhoods, with gentle densification – of the kind being championed by Jane Jacobs in Toronto – the order of the day. “We brought planners out into communities to work with them on everything from traffic patterns to zoning to housing development,” Marzari says.

The city acquired huge amounts of parkland, setting up agricultural land reserves that to this day act as bulwarks against overdevelopment. Many of Vancouver’s signature attractions, including Granville Island, False Creek and the seawall, were developed or revitalised in the wake of the anti-freeway victory, either by Team or by its successors in the late 1970s and 80s.

“We weren’t smarter, we were later. We learned from the mistakes of Seattle and LA,” says Bing Thom, a prominent Vancouver architect. He credits the city’s success to, among other things, timing and sensibility.

“One of the legacies of the protests was that they created an appetite and appreciation for critical debate. We have had enlightened civil servants and an educated citizenry. Everyone has an opinion, and you can talk logic and ideas even if you disagree.”

When, last year, the City of Vancouver announced that the viaducts would be demolished, it felt to Chan like a final, symbolic victory. “I feel relieved,” she said. “I hope … to see the community reknit across the no man’s land which has been there for more than 40 years.”

Symbolism aside, the reality is that the viaducts sit on land that is now too valuable not to redevelop. Since the late 90s, and particularly in the last few years, property values have soared. As the city has become famous for its liveability, global capital has poured in, much of it from wealthy Chinese keen to park their money in a beautiful and economically stable place.

“Let’s be clear, [the investors driving up real estate prices] are a tiny segment of the Chinese people who immigrate to the city; 99% face the same affordability issues as everyone else. It’s a class issue,” Thom says.

He doesn’t see an end to the trend anytime soon. “This is the reality of unchecked globalisation. Vancouver is a small city and the scale of change is the same as New York or London, so it affects us much more. It’s inevitable that people are going to start asking themselves questions,” he says.

Questions like: what is Vancouver today, and who is it for?