Articles Menu

November 29th 2018

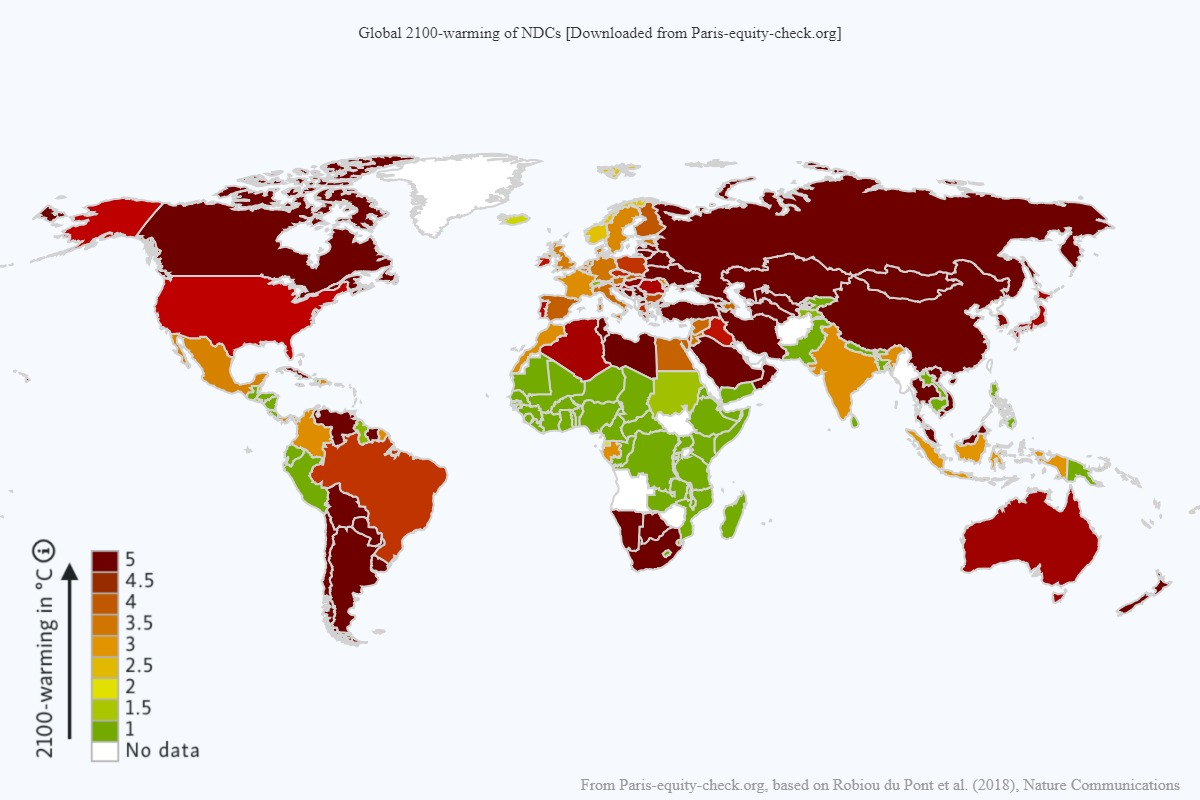

Canada’s current climate policies are "very insufficient" and would help increase global temperatures by a catastrophic 5 C by the end of the century, according to a new study that ranks the climate goals of countries around the world.

The study found that Canada, along with Russia, China, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and a dozen other countries, are dangerously contributing to the global temperature rise, and is on course to vastly exceed the 1.5 C that scientific research assessed by the IPCC found is a moderately safe level of global warming.

Canada has also portrayed itself as a climate leader. Environment and Climate Change Minister Catherine McKenna regularly speaks about the urgency of addressing climate change, while promoting the government's actions, including plans to introduce a national price on carbon in 2019, as part of the solution.

"We have a real plan to protect the environment and grow the economy — and it’s working," McKenna said on Twitter on Thursday. "Canada’s economy is growing, our emissions are dropping, and, once fully implemented, our plan will achieve the largest reduction in projected emissions in our country’s history.

[see link for tweet here]

The new study, published on Nov. 16 in the journal Nature Communications, assesses each nation’s ambitions and goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the temperature rise that would result if the world followed their example. A supplementary data visualization website called Paris-Equity-Check.org presents these results.

The study's author Dr Yann Robiou du Pont from the University of Melbourne’s Australian-German Climate and Energy College said its aim is to help inform politicians and climate leaders as the United Nations begins a two-year process of re-assessing global climate commitments, which numerous studies have now found fall far short of the 1.5-2 C goal set in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The discussions will begin next week with a crucial two-week climate change conference in Katowice, Poland, known as “COP 24."

The Paris agreement set a deadline of 2018 for all signatories to adopt a work program for the implementation of their emissions reduction commitments which will include a financial plan for climate action worldwide.

At the time, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau committed to achieve an economy-wide target to reduce Canada's greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

But, in order to meet the Paris Agreement, Canada should be looking to decrease their emissions by nearly 70 per cent, said Robiou du Pont.

"The aggregation of commitments of countries is insufficient to limit world's global warming," Robiou du Pont told National Observer in a phone call from Berlin. "The current policies and plans are not even sufficient to meet the goals they have now. We need to talk about how they can increase their emissions reduction targets and, more importantly, deliver their targets."

“This metric translates the lack of ambition on a global scale to a national scale," he said.

Many environmentalists have also criticized the government for not doing enough to address climate change, including policies, such as its purchase and promotion of the west coast Trans Mountain oil pipeline expansion project, that could drive emissions higher.

As part of the Paris climate accords of 2015, each nation made pledges to take action to reduce its contribution to global warming, known as Nationally Determined Contributions. The Paris agreements recognized that a top down solution to global warming imposed by the United Nations or similar organization would be ineffective, so the bottom up process of letting each country establish its own targets was adopted.

Each country's pledge would account for their historical contribution to global warming and its financial capacity to de-carbon its economy, and would explain how their goal is "fair and ambitious" - a mandate required by the Paris agreement.

"The issue is that different countries have different understandings of what is fair and ambitious," said Robiou du Pont. "There is no scale, no unique metric to really see how ambitious each country is...there are as many metrics as there are visions of equity."

This makes is difficult to quantify and keep track of the 2030-emissions goals, he said. There is no consensus on what is a fair share of responsibility; rather, it is up to each individual country to set its own targets based on their own interests and measures.

[see link for video]

That's why the study doesn't factor in emissions produced as a result of land-use changes like deforestation, because every country has a different standard and weight to such climate-contributing activities.

"You need a way to account for parameters," said Robiou du Pont. "You need to have a universal measure of responsibility, capability and equity to be effective."

Still, the results show that the international communities' efforts are, unsurprisingly, lackluster. At present, the 2030 emissions reductions goals for the world's eight largest industrialized economies and China are 21 per cent lower than what they should be to meet the 1.5 C target, and 39 per cent lower for all other countries.

To improve on that, Robiou du Pont said that more stringent action is required of individual countries to achieve mitigation milestones, such as reaching net-zero emissions around a decade earlier than their 2030 goals.

“If we disagree on what is equitable and let each country pick the least stringent approach, then we have to be more stringent on the collective goal,” he said, noting that the next phase in his research is to calculate the emissions targets that states/provinces/territories could take to meet the Paris Agreement in individual countries.

Collectively, the results could then be used in climate litigation cases against countries, to hold governments to account from stronger climate action, such as the landmark 2015 Urgenda Climate Case against the Dutch Government, which was the first in the world in which citizens and the courts successfully held their government accountable for contributing to dangerous climate change.

The Paris equity study comes along with several others that all warn of dire consequences due to inadequate climate action policies worldwide.

Two days ago, on Nov. 27, a United Nations report also found that the current emission targets for all countries would result in an average global temperature rise of 3.2 degrees Celsius by 2100.

On Thursday, the World Meteorological Association found that the 2018 average global temperature is set to be the fourth highest on record. The last four years were the four warmest on record and the 20 warmest years have occurred during the last 22 years, it found.

"For each 3-month period until September 2018, ocean heat content was the highest or second highest on record. Global Mean Sea Level from January to July 2018 was around 2 to 3 mm higher than the same period in 2017," the report stated.

[see link for video]

And in October, a study found that more than 70 per cent of our planet’s remaining areas of wilderness are contained in just five countries, including Canada, Russia, Australia, the US and Brazil, and urged for more wildlife conservation report. The World Wildlife Fund also reported that global wildlife populations have fallen by 60 per cent in the last four decades.

Robiou du Pont said the Paris agreement was is including many countries in this global effort to tackle climate change. "But now we have to align all these countries' goals. Now we need a metric," he said. "They have not agreed on how to do do this. Maybe this study will help."