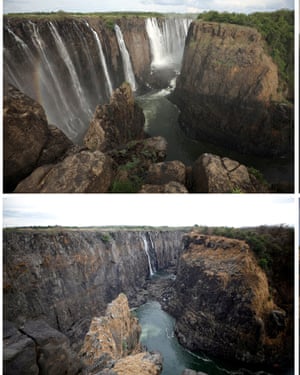

For decades Victoria Falls, where southern Africa’s Zambezi river cascades down 100 metres into a gash in the earth, have drawn millions of holidaymakers to Zimbabwe and Zambia for their stunning views.

But the worst drought in a century has slowed the waterfalls to a trickle, fuelling fears that climate change could kill one of the region’s biggest tourist attractions.

While they typically slow down during the dry season, officials said this year had brought an unprecedented decline in water levels.

“In previous years, when it gets dry, it’s not to this extent,” Dominic Nyambe, a seller of tourist handicrafts in his 30s, said outside his shop in Livingstone, on the Zambian side. “This [is] our first experience of seeing it like this.

“It affects us because ... clients ... can see on the internet [that the falls are low] ... We don’t have so many tourists.”

As world leaders gather in Madrid for the COP25 climate change conference to discuss ways to halt catastrophic warming caused by human-driven greenhouse gas emissions, southern Africa is already suffering some of its worst effects – with taps running dry and about 45 million people in need of food aid amid crop failures.

Zimbabwe and Zambia have suffered power cuts as they are heavily reliant on hydropower from plants at the Kariba dam, which is on the Zambezi river upstream of the waterfalls.

Stretches of this kilometre-long natural wonder are nothing but dry stone. Water flow is low in others.

Data from the Zambezi River Authority shows water flow at its lowest since 1995, and well under the long-term average. The Zambian president, Edgar Lungu, has called it “a stark reminder of what climate change is doing to our environment”.

Yet scientists are cautious about categorically blaming climate change. There is always seasonal variation in levels.

Harald Kling, a hydrologist at engineering firm Poyry and a Zambezi river expert, said climate science dealt in decades, not particular years, “so it’s sometimes difficult to say this is because of climate change because droughts have always occurred”.

He said early climate models had predicted more frequent dry years in the Zambezi basin, but that “what was surprising was that it [drought] has been so frequent” – the last drought was only three years ago. As the river got hotter, 437m cubic metres of water were evaporating every second.

In Livingstone this week, four tourists stared into a mostly dry chasm normally gushing with white water. German student Benjamin Konig was disappointed.

“Seems to be not much [water] – a few rocky stones with a little water between it,” he said.

Richard Beilfuss, head of the International Crane Foundation, who has studied the Zambezi for the past three decades, believed climate change was delaying the monsoon, “concentrating rain in bigger events, which are then much harder to store, and a much longer, excruciating dry season”.