And it sheds light on how symbiotic government regulators, public pension managers, and energy corporation minnows and whales alike have become in Canada. It’s a tale with a few twists, so settle in.

It starts with a simple fact. In the last five years the Alberta Energy Regulator, which is funded by the industry, has watched cash-rich companies sell or trade off more than 150,000 inactive or uneconomic wells to small firms that didn’t have the financial ability to perform mandated well cleanups.

A flaw in the proposed deal, said the regulator, was that it had no way to know how much land and water Shell’s operations had poisoned. The “scope and extent of the contamination at the sites is not well known.” Nor could groundwater contamination be distinguished from other ongoing pollution at Shell’s aging sour gas plants.

“Shell is the polluter,” added the regulator, and also the operator under Alberta’s reclamation laws and “therefore required to conserve and reclaim the sites.”

The ruling added, “Trying to manage and enforce different reclamation obligations amongst different approval holders would be inefficient, disorderly and extremely burdensome.”

Given that’s the case, let’s further set the stage. Alberta is a province where the majority of oil and gas companies now own more inactive and uneconomic wells than they do producing ones. In fact, their liabilities exceed assets due to depleted and aging geologies, insolvent fracking companies and volatile commodity prices.

Let’s preview as well a few more characters in this particular petroleum soap opera. It not only involves Shell, which posted profits of $16.5 billion last year, but also an until recently tiny Calgary firm, three large and toxic sour gas plants and fields, a bunch of German bankers and energy traders, a scandal-plagued regulator, and a speculative LNG play in Nova Scotia.

One more twist is that the Alberta Investment Management Corp. — the province’s embattled pension fund manager that just lost billions of dollars on the stock market — may lose billions more with investments in ailing oil and gas companies.

How large are the wider stakes? Very large indeed. The regulator’s ruling comes amidst a toxic boondoggle in the extreme. In Alberta, the unfunded cost of cleaning up 400,000 wells, half of which are now inactive or uneconomic, is estimated to be $100 billion. Only an inadequate $229 million in security deposits has been set aside for the job. Someone’s got to pay up eventually. Companies, if they can, will stick citizens with the bill.

Which is just what Mike Judd was thinking when he decided to sound his alarm.

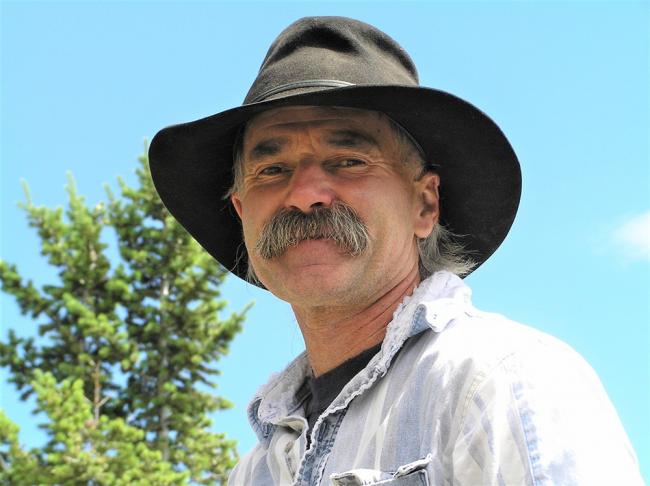

I. THE COWBOY WHO FIRED OFF A LETTER

Mike Judd is a 70-year-old retired backcountry outfitter with a lean frame and bristly mustache, who once got so mad at the digital craziness his computer represented that he shot it. He lives near Shell’s gas plant in Waterton in southern Alberta on land where a grizzly bear dens.

When Judd learned last year that Shell was selling off its three aging sour gas plants in the eastern slopes of the Rockies to a small Calgary company for $190 million, he couldn’t believe his ears.

As a landowner who had frequently contested Shell’s intrusions into the Rockies, Judd estimated that the clean-up cost of Shell’s aging wells might be billions of dollars. Many of the sour wells, among the deepest in the province, are located on the sides or on the tops of mountains.

Like most landowners, Judd also knew the nature of the reclamation game in Alberta and other oil-producing jurisdictions. For decades the oil and gas industry has resorted to two strategies for avoiding the cost of cleaning up its inactive and depleted wells: go bankrupt or pawn off aging assets to smaller companies without the resources to honour regulatory clean-up obligations.

“It’s common practice in the industry to package up non-producing wells, dry holes, wells that are problematic, with a few really nice good wells and then sell them to a smaller or medium-sized company,” Keith Wilson, an Edmonton-area property rights lawyer explained to the Canadian Press last year.

Each company in the chain milks the remaining assets until the cost of decommissioning them outweighs the costs of keeping them active.

At that point industry often dumps its liabilities onto the lap of the industry-funded Orphan Well Association or increasingly onto Canadian taxpayers.

So many firms have walked away from their clean-up liabilities in recent years that the Orphan Well Association is now supported by more than a half billion dollars’ worth of repayable loans from the Alberta government and Ottawa.

In other words, taxpayers are footing the bill for oil and gas well cleanups — a scenario that industry and energy regulators swore would never happen in Canada.

Judd also knew that successive Alberta Tory governments had failed to collect adequate deposits for what the regulator now estimates amounts to a $100-billion cleanup just for wells alone. (The total unfunded bill for decommissioning zombie wells, pipelines and oilsands facilities equals $260 billion, according to the regulator.)

Judd also knew that the regulator had set up a liability management program based on outdated oil prices so companies with aging wells could claim to be more solvent than they were. The regulator also refused to set a time limit for cleaning up inactive wells.

Fearing he was about to see the whole cycle unfold in his own backyard, Judd asked a public interest lawyer what he could do to prevent the sale. The lawyer told Judd that he could file a statement of concern with the Alberta Energy Regulator asking for a public hearing.

And so last November Judd wrote his letter to the regulator: “I am concerned the transfer of the Waterton Field licenses to a small operator is the first step towards my home being surrounded by dangerous orphaned oil and gas equipment that may never be reclaimed.”

Judd sent off the plea with lowered expectations. Certainly he didn’t expect the avalanche of resistance it triggered.

II. THE LITTLE ENERGY FIRM WITH HUGE AMBITIONS

Pieridae Energy, formed in 2011, is a small Calgary-based firm professing aspirations of the boldest order. It proposes to build a $10-billion liquefied natural gas facility in Goldboro, N.S. to supply European markets.

At various times Pieridae has proposed sourcing that methane from potential shale developments in Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Pennsylvania. Now it wants to pipe methane from Alberta’s sour gas fields all the way to Nova Scotia. (Sour gas has a 15 per cent higher greenhouse gas footprint than conventional gas because of all the processing required to remove the sour part: hydrogen sulfide.)

On its website Pieridae Energy explains the company was founded as a “second go around” for its key management team to champion LNG developments.

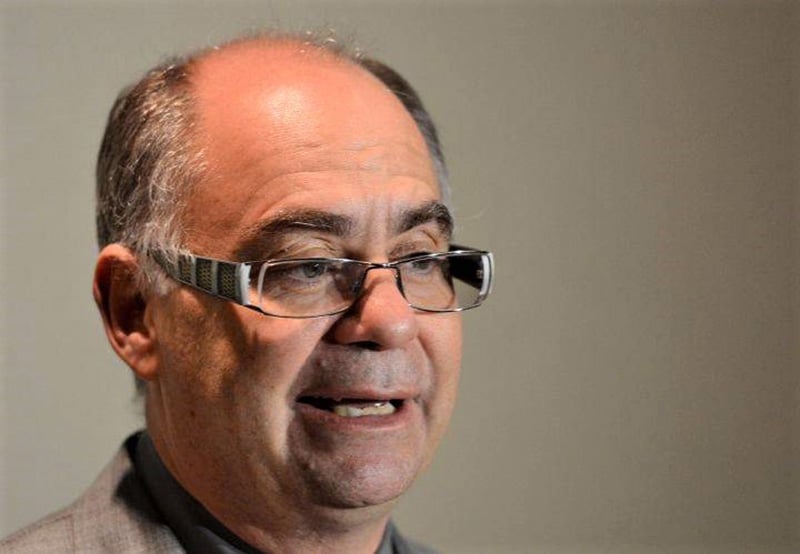

The first go around? That was the Kitimat LNG project on the West Coast, led by Alfred Sorensen, an accountant by trade and former energy trader for Duke Energy.

Sorensen, possessing an upbeat nature and a bespectacled face that is owl-like, sold that project to Apache and EOG Resources for $300 million in 2010. He personally pocketed $30 million. Pieridae boasts that it was “the first liquefaction facility permitted in North America in 40 years.” But the website doesn’t add that it never got built.

As shale gas prices dropped, Apache and EOG sold their stakes in 2015 to Chevron and Australia’s Woodside Petroleum. When LNG prices collapsed this year due to overproduction and then the pandemic, Woodside posted a billion-dollar write down on the project. Chevron also took a $1.6-billion write down on its share.

Given current market conditions, it is unlikely Kitimat LNG will ever be built.

But Sorensen, dubbed “Canada’s LNG marathon man” by the Globe and Mail, pushed on with the proposed Goldboro terminal in Nova Scotia even as methane prices languished and investment capital grew skittish.

He acquired a terminal site and environmental permits and even lined up Uniper, a German energy trader, to buy half the gas.

At the same time, he served as a CEO of Canadian Spirit Resources, a small six person shale gas company, from 2013 to 2015. But it too mirrored the industry’s fragile economics. After buying land and identifying 1,200 potential shale gas wells in the Montney Formation in B.C., Sorensen shopped around for a buyer.

In 2012 he told Alberta Oil Magazine, “That’s what I think my bigger skill set is — selling things.” He paused and added, “As long as you’re not selling something that’s not real, I suppose.”

Canadian Spirit Resources never did find a buyer. Last year the company posted no gas or liquids revenue, and its share price has dropped to four cents. Its chief financial officers left the company this spring.

Meanwhile Sorensen tried to build Pieridae into an attractive story. In 2017, he took the company public by merging with a Quebec firm, Petrolia, which owns the most oil and gas permits in that shale-rich province.

Petrolia’s biggest claim to fame was being awarded in compensation by the Quebec government after it banned any drilling on Anticosti Island where Petrolia held leases.

Pieridae Energy advertised the merger as “an opportunity for investors to participate in the evolution and growth of Canada’s only integrated LNG facility.” But the merger never really attracted the level of investment needed to get the project off the ground.

Alberta’s pension funds manager, which has a poor track record in backing oil and gas plays (see sidebar), then loaned Pieridae $50 million and bought $10 million worth of its stock.

Still, until Pieridae bought Shell’s 70-year-old gas operations in 2019 pending approval by the Alberta Energy Regulator, the company had few resources and even less cash.

Just the year before, Royal Dutch Shell posted revenues of $396 billion, while Pieridae recorded a net loss of $34 million. How then did little Pieridae manage to buy Shell’s sour gas properties? By borrowing $206 million from Third Eye Capital, a Toronto firm that specializes in loaning money to distressed or risky companies.

What Pieridae actually bought was this: 284 deep sour gas wells; 66 facilities and 82 pipelines nearly 1,700 kilometres in length at three of Shell’s sour gas fields in Waterton, Jumping Pound and Caroline. The highly corrosive nature of sour gas requires constant and expert care. To provide it, 200 Shell staff became Pieridae employees.

Shell, meanwhile, vowed to take care of extensive groundwater contamination at the gas plants while Pieridae would become responsible for cleaning up the wells and pipelines and three massive sour gas plants at some later date.

Although Shell described Pieridae Energy as “an experienced operator” in its press release, few observers agreed with that assessment.

Shaun Fluker, a University of Calgary law professor who has watched marginal companies operate in the patch for years, told The Tyee that, “I don’t think there is any credible operator on the planet who would agree to take on this kind of aging infrastructure with those kind of liabilities. The cost of cleaning it up will be astronomical.”

He suggested that Pieridae’s purchase from Shell was part of a larger strategy to make the company more appealing for prospective buyers and to reassure potential German investors that it had some methane to fill its proposed terminal. Pieridae, said Fluker, just needed “the assets to tell part of their LNG story. It is a house of cards and the company has no intention of doing that reclamation work.”

Pieridae has been adamant throughout that it would see through any clean up it was now on the hook to deliver.

III. THE AVALANCHE

The avalanche that Judd’s letter of concern set off included more letters by dozens of landowners, companies and pension holders questioning the purchase.

Upset pension holders warned that AIMCo’s investments in Pieridae Energy might result in the manager becoming liable for billion-dollar cleanups down the road. “Pieridae, a distressed company, is seeking and receiving financial capital from AIMCo to pay for this license transfer project thus jeopardizing my pension plan,” wrote retired social teacher Rose Marie Sackela living in central Alberta.

On Judd’s side, too, were two of the biggest names in Alberta’s troubled oil patch. Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. and Cenovus also strongly objected to the deal.

“If Pieridae were to become insolvent, there is a high probability that Pieridae’s abandonment and reclamation liability will fall to the Orphan Fund,” wrote CNRL in its letter of concern. (The company has objected to many similar transactions for the same reasons.)

Because CNRL is the largest contributor to the orphan well fund, it worried that it might be on the hook for $100 million worth of the eventual clean up of Shell’s deep sour gas wells.

The company, owned by billionaire Murray Edwards, added that “there is a high probability that Pieridae will experience a financial distress with continued low gas prices,” as have most methane producers on the continent.

The Orphan Well Association, which was created by government and industry as a last resort for cleanups, also objected to the transfer. It argued that Pieridae didn’t have the leadership or financial resources to decommission what they estimated to be a $500-million liability.

The OWA, which rarely addresses Alberta’s clean-up failings in public, also criticized the regulator for not doing its job. It didn’t think the regulator had a proper process for vetting the transfer of licences from cash-rich companies to cash-poor ones.

More damningly it stated “that the current regulatory system for assessing the overall financial viability of asset transfers is not adequate and needs to be augmented.”

As the statements of concern rolled in, most of them asked the regulator to refuse the transfer of licenses to Pieridae, or at the very least require Shell to set aside at least a hefty clean-up fund worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

But that’s not how Shell and Pieridae saw the deal. They replied that Albertans had nothing to worry about.

Shell said that the energy regulator and the public shouldn’t be concerned because the province had “a robust system for ensuring that companies are held responsible for the environmental liabilities resulting from energy development.”

In fact, however, in 2018 Robert Wadsworth, the Alberta Energy Regulator’s vice-president for well cleanup, admitted in a public presentation that the system was broken. He said the collection of security funds from industry was “insufficient” due to a “deeply flawed” system for monitoring liabilities.

Alberta’s Liability Management Rating program had tracked inactive wells in the oil patch for nearly two decades. But it didn’t collect money for cleaning up abandoned wells until the companies were “already showing declining financial capacity,” said Wadsworth.

Nevertheless, Pieridae Energy referred to Alberta’s regulatory system as “robust” too. Sorensen’s firm added that it was “uniquely situated to benefit from certain German federal government loan guarantees for up [to] US$4.5 billion which have been approved in principle under a German untied credit program.”

Pieridae said most of the loan would go to the construction of the LNG facility in Goldboro but that $1.5 billion would help finance the extraction of more deep gas from Alberta’s foothills without the use of fracking.

One of the conditions of the German government loan is that no fracked gas be used to supply the LNG terminal because Germany has banned the technology.

Thanks to ongoing production from Shell’s aging sour gas fields, Pieridae said, it would be able to “generate net cashflow sufficient to satisfy all of Pieridae’s legal obligations including the environmental obligations” of decommissioning Shell’s sour gas wells, pipelines and sour gas plants.

The company added that CNRL’s concerns were frivolous and self-interested. In a low-price market “it is possible that CNRL is seeking to gain a competitive advantage by exaggerating its concern of the risk regarding this asset acquisition.”

IV. THE BILLION DOLLAR NEXT PITCH

While the Alberta Energy Regulator pondered these arguments in January, Sorensen sat down with federal Natural Resources Minister Seamus O’ Regan to make a friendly LNG pitch.

Sorensen, who is such an aficionado of dance as high art that he chairs the Alberta Ballet Foundation, explained to O’Regan how his proposed LNG terminal in Nova Scotia would ship “sustainably-produced natural gas to the world.”

In his marketing spiel Sorensen emphasized that his project would really help the government of Canada meet three key goals: support reconciliation with First Nations with benefit agreements, “address global GHG emissions by using cleaner-burning LNG to replace coal,” and, lastly, “get our resources to market along with creating good-paying middle-class jobs.”

It’s not known whether Sorensen mentioned to O’Regan the findings of a 2018 analysis on the economics of exporting LNG from Canada. The Canadian Energy Research Institute, which is partly funded by the government, concluded any project would need at least a $100 oil price or $11.6 per million British thermal units over the life of the project to be viable. (The European Union natural gas import price is currently $2.12, a nearly 60 per cent drop from last year’s $4.90 per million British thermal units.)

The CERI report said such “a viable path” didn’t currently exist in Eastern Canada and if it did it would have to use fracked gas from Nova Scotia or New Brunswick where opposition to the technology remains fierce. (In fact, several anti-fracking groups have protested potential German funding for Pieridae on these very grounds.)

Four months after his meeting with O’Regan, Sorensen announced that Pieridae Resources was putting off its Final Investment Decision on the LNG plant, as he has done routinely since 2013, for another year. This time he blamed rock-bottom LNG prices and the pandemic.

But the ever-optimistic Sorensen added on an April 16 conference call that that he would continue lobbying the federal government and provincial government for financial help. He suggested a billion dollars would do the trick.

“We’re looking for a hand up, not a hand out,” he said.

Representatives of Maple Leaf Strategies, which served as chief strategist and pollster on Premier Jason Kenney’s successful election in Alberta in 2019, are now listed as the company’s Ottawa lobbyists.

As the AER decision was pending, The Tyee asked Pieridae Energy how it proposed to pay for decommissioning the sour gas assets it bought from Shell given its limited resources, and the fact that no money-making LNG terminal yet exists.

James Millar, director of external relations, replied, “The cash flow from decades of productive life in these assets will provide the necessary reclamation costs.” He said the company’s total revenue in 2019 was $114 million on the production of 40,000 barrels of oil equivalent from Shell’s sour gas fields.

Millar added, “We are sound financially and have a solid plan going forward for the rest of 2020 and beyond.”

He noted that the global LNG industry “has obviously not been immune to the negative impacts of COVID-19,” and that nearly a dozen LNG projects have been cancelled or delayed.

“This is not the case for our multibillion dollar Goldboro LNG Project. We continue to push forward and we announced a positive development recently as Pieridae has negotiated extensions of deadlines under its 20-year agreement with German energy company Uniper Global Commodities.”

The Tyee also asked Uniper, the German energy trader, if it had any concerns about Pieridae’s ability to pay for the decommissioning costs of Shell’s sour gas plant.

The company, which first signed a deal with Pieridae in 2013 for half the capacity of the proposed LNG plant, replied: “Please understand that we don’t comment on this.”

V. THE BIG NO

In its decision release on May 13, the Alberta Energy Regulator firmly blocked Shell from transferring the ownership of its sour gas leases to Pieridae Energy. The nub of the decision: having Shell be responsible for groundwater pollution and Pieridae responsible for well clean up simply violated the law.

But the regulator conspicuously didn’t say a word about Pieridae’s financial ability to decommission at least a billion dollars worth of liabilities.

The Tyee sent queries to the regulator while it was trying to make up its mind. Its response took a week and came after the agency posted its decision. So what did the AER make of Pieridae’s ability to take on Shell’s massive clean-up liabilities, and how did such a deal even get this far?

Shawn Roth, a specialist in external relations for the Alberta Energy Regulator, allowed that his employer might have room to improve in how it goes about its responsibilities. The AER, Roth told The Tyee, is aware that its system for tracking liabilities “is not a good indicator of a company’s financial health. We are working to broaden our assessment processes to allow for a more holistic approach to assess a company’s ability to address its end-of-life obligations and have contributed to the Government of Alberta’s review of the liability management system.”

Shell did not reply to two separate queries from The Tyee.

After the AER rejected its deal with Shell, Pieridae Energy released a public statement the following day by CEO Alfred Sorensen. He said, “We are all disappointed.”

The LNG marathon man added, “The decision has nothing to do with Pieridae’s financial position nor its ability to clean up certain assets. The issue for denial was the fact that there is no precedent for splitting a licence or no ability under the current legislation to do so.”

Sorensen, like a runner with his eyes fixed on a distant horizon, said the company is confident a solution will be found.

Eoin Finn, a former partner in KPMG who tracks the volatile economics of LNG, wonders why or how that could happen. And if Pieridae does manage to win over the Alberta Energy Regulator, allowing it to take on Shell’s clean-up liabilities, a few aspects would deeply concern Finn.

For obvious starters, “if I were the regulator, I would be worried about Pieridae’s financial position and its ability to clean up after the sour gas wells peter out,” Finn said. He also noted that the $206-million loan Pieridae had used to buy Shell’s assets carried an interest rate of 15 per cent which means the company must find $31 million in interest charges every year or face foreclosure. And there’s the bothersome fact that one of the contractors Pieridae had lined up for its LNG terminal declared chapter 11 bankruptcy in January.

As for Mike Judd, these days he feels like a man who stopped a robbery in progress.

He told The Tyee he figures the Alberta Energy Regulator had no choice but to refuse the deal because it had come under so much heat over its repeated failure to address the province’s well clean-up liabilities.

“The companies have made out like bandits in Alberta,” said Judd. “They prospered under one of the poorest regulatory regimes in North America, and paid few royalties and now they want the taxpayer to clean up their messes when they dump their pollution liabilities onto small companies. That to me sounds like a perfect heist.” ![]()