Articles Menu

Greta Thunberg has become so firmly entrenched as an icon — perhaps the icon — of ecological activism that it’s hard to believe it has been only two years since she first went on school strike to draw attention to the climate crisis. In that short time, Thunberg, a 17-year-old Swede, has become a figure of international standing, able to meet with sympathetic world leaders and rattle the unsympathetic. Her compelling clarity about the scale of the crisis and moral indignation at the inadequate political response have been hugely influential in shifting public opinion. An estimated four million people participated in the September 2019 global climate strikes that she helped inspire. “There’s this false image that I’m an angry, depressed teenager,” says Thunberg, whose rapid rise is the subject of “I Am Greta,” a new documentary on Hulu. “But why would I be depressed when I’m trying to do my best to change things?”

What do you see as the stakes for the U.S. presidential election? Is it a make-or-break ecological choice?

We can’t predict what will happen. Maybe if Trump wins that will be the spark that makes people angry enough to start protesting and really demanding things for the climate crisis. I think we can safely say that if Trump wins it would threaten many things. But I’m not saying that Joe Biden is good or his policies are close to being enough. They are not.

Last year there was that video of you at the U.N. glaring at President Trump. I’d wondered if maybe that was a split-second facial expression that then got blown out of proportion. Can you remember what you were thinking then?

I don’t think you need an explanation. I think people could see for themselves.

A second ago you said that Joe Biden’s climate policies are not good enough. I get that his plan or the Green New Deal is insufficient in the face of how, according to most estimates, the United States is overspending its emissions against the global carbon budget.1

But these kinds of plans are being discussed in a serious way, which was not happening five years ago. Is it possible that the nature of democratic politics is such that changes might not come as quickly as they need to in order to keep us below certain thresholds of global warming?

When we say “greener policies,” what does “green” even mean? Green is a color. So when people say that we are going to invest in green investments, that can mean anything. The Green New Deal is very far from being enough, but as you said, it has changed the debate. It could be a small step in the right direction, and that’s the way we have to communicate it. To say, “This is far from being enough” and then always show where we need to be.

To what extent do you think your work as an activist should involve thinking of solutions to climate problems? Or do you see your role as more symbolic? I’m not a scientist. I’ve intentionally stayed out of speaking about specific things and about politics because that’s not up to us children to do. That would be strange.

When you say “us children”

— Technically and legally I am a child.

You are, but I bet there are lots of 17-year-olds who don’t want to be thought of as children even if technically and legally they are. Are there ever times when you’d rather be thought of as an adult?

I don’t care about whether I’m considered as a child or an adult. I want to be met with the response that’s on my level. But yeah, I guess when I turn 18, I’m going to switch to describing myself as an adult. That’s a very autistic way of seeing things. People say: “She’s trying to frame herself as a child so that people can’t criticize her. She’s using that as a shield.” No. I’m autistic, and I say things in the way they are.

Greta Thunberg with her “school strike for climate” sign in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 2020. Stefan Wermuth/Agence France-Presse, via Getty Images

I definitely understand that on some level it’s ridiculous to ask a 17-year-old about complicated geopolitical problems, but by the same token, you’re not 10 and you are a leader. Is there an age at which you would consider it reasonable for people to expect that you have ideas about solutions?

Right now, I spend I don’t know how much of my time reading and trying to learn, but that doesn’t mean I’m an expert. So I choose to hand over that debate to those who know more than I do. I know maybe more about communicating, so that’s what I’m going to stick to, where I can be most helpful. The mainstream communication strategy for the last decades has been positivity and spreading inspiration to motivate people to act. Like: “Things are bad, but we can change. Just switch your light bulb.” You always had to be positive, even though it was false hope. We still need to communicate the positive things, but above that we need to communicate reality. In order to be able to change things we need to understand where we are at. We can’t spread false hope. That’s practically not a very wise thing to do. Also, it’s morally wrong that people are building on false hope. So I’ve tried to communicate the climate crisis as it is.

Which means with clarity, and in the past you’ve attributed that clarity to your Asperger’s syndrome — you’ve even called it your superpower. Are there any ways in which Asperger’s is a hindrance?

It could be, if you see it in the way of having a normal life. It makes me different. I don’t spend time hanging out with friends, because I’m bad at socializing. You could see that as hindrance, but I don’t, because I don’t need to do that to survive. I don’t feel the need to do things that others might.

Do you feel you have clarity about political or moral issues beyond the climate crisis? Are there any in which you see gray?

There’s a misconception that I see the world in black and white. Of course I don’t see the world in black and white. It’s just that when it comes to the climate and environment, you can’t be a little bit sustainable. Either you are sustainable or you are unsustainable. Why I was able to act upon the crisis without people around me doing it was because most people follow social codes, but people with Asperger’s and autism, we don’t follow social codes. We don’t care what people think about us. That’s why I started to act, and I strongly believe it’s why people on the autism spectrum are overrepresented in the climate movement.

There’s a part in “I Am Greta”2 where you talk about how you don’t get invited to parties and mostly spend time with your family. Has your social life — or your feelings of being accepted or not — changed since you’ve become so well known?

Before I started school-striking I basically only spoke to the adults I trusted. I found people my own age completely uninteresting. They didn’t care about me. They didn’t talk to me. But then I started school-striking, and I remember feeling it was so strange, because people actually looked at me. They had never done that before. I had always been invisible, and suddenly I wasn’t invisible. They started acknowledging that I was there. They started to take pictures with me. In the beginning it was hard, because I didn’t understand. When a group of children approached me, I became scared because I thought they were going to treat me badly, as they had always done. So sometimes I became overwhelmed and had to go away, because I was too scared of them. That was very strange — from one reality to a complete other reality almost overnight.

Thunberg in the new documentary ‘‘I Am Greta’’. From Hulu

Do you now find it any easier to relate to other people your age?

No. I still don’t really know what people my age are like or how they behave.

You took a gap year off from school to do activism. How is it to be back in class? I know these are the kind of questions that you probably think are absurd, but I’m curious about your life.

That’s OK. It sometimes gets awkward: In Sweden we have this phenomenon called Jantelagen.3 It’s when someone is famous, and the people around use up all their energy to ignore the fact that the person is famous. I can tell you one example. Today I was at a museum, and there was an exhibition. I was mentioned in the exhibition I think four times. There was a huge picture of me hanging in the museum and in the gift shop they sold my books.4 Yet no one stepped forward and said, “Are you Greta?” They just looked at me. I know that they know that I know. It becomes socially awkward. We have that culture in Sweden.

Are you able to find time in your life to do things for pleasure?

Of course. I do jigsaw puzzles. I watch lots of documentaries, and I read a lot. I am with my dogs. But I also enjoy working. It’s not like I’m sacrificing my spare time to do that. I chose to do that.

This summer you co-wrote an open letter calling for an immediate halt to all investment in fossil fuel exploration and extraction. That’s not going to happen. But is the hope that uncompromising demands are the best path to the greatest positive change?

Yeah. A good example is that if you have someone in your family who is always late, you say, “The party starts at 6,” and then that person comes at 7. But in reality the party started at 7. It’s all about communicating the crisis mode: If we are to stay in line with the carbon budgets which give us a 66 percent chance of staying below 1.5 degrees of global average temperature rise above pre-industrial levels, then here is what we have to do. The people in power say: “We’re going to stay in with the Paris Agreement. We’re going to stabilize below 1.5 degrees.”5 They say that and get away with it because the level of knowledge is so low.

Thunberg with Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, as they announce a new EU climate deal in March in Brussels. Leon Neal/Getty Images

What have you learned about people in power?

I’ve spoken to many world leaders, and sometimes I wish I had a hidden camera. People wouldn’t believe what they say. It’s very funny. They say: “I can’t do anything because I don’t have the support. You need to help me.” They become desperate. It’s like they are begging for me to help them persuade the public that we need climate action. What that tells me is people are underestimating their power and the power of democracy and of putting pressure on people in power. They can’t do anything without support from voters.

How do you make sure that you’re not being used as a prop when you meet with politicians?

That’s probably most often the only reason they meet me. But you need to be able to have conversations, and I don’t say, “I had a meeting with Angela Merkel or Emmanuel Macron and they really seem to get it.” I don’t make them look good. That’s one thing I can do. People see through when politicians try to hide behind me.

Is there a political leader whom you think does seem to get it?

No.

Let me ask about individual action and the climate crisis. You’ve said elsewhere that you’re not telling people that they should become vegan or stop flying,6 but that they should look at the science and act accordingly. Do you worry that people see the science, become overwhelmed and then decide that their individual choices won’t make any difference? Or only make changes that don’t inconvenience their lives? I know it’s a moral failing, but both those scenarios pretty much describe my behavior and, I think, a lot of other people’s.

It’s true that if one person stops eating meat and dairy it doesn’t make much difference. But it’s not what one person does. This is about something much bigger. Some studies have done testing on four different conditions. The first group of households was told, “You should reduce your energy consumption because you can save money.” To the second group they said, “You should reduce your energy consumption because of the environment.” The third, it was like, “Think of your children’s future.” The fourth group was told how their energy consumption compared to their neighbors’. It became a competition. The fourth group more than others reduced their energy consumption. It shows how we are social animals. We copy each other’s behavior. I didn’t stop flying or become vegan because I wanted to reduce my personal carbon footprint. It would be much more useful for me to fly around the world advocating for climate action. But it’s all about sending a signal that we are in a crisis and that in a crisis you change behavior. If no one breaks this chain of “I won’t do this, because no one else is doing anything” and “Look at them. They’re doing much worse than I am” — if everyone keeps on going like that, then no one will change. We won’t understand that we are in a crisis. If people don’t understand that we are in a crisis, they won’t put pressure on people in power. If there’s no pressure on people in power, then they can continue to get away with doing basically nothing. But if you fully understand the science, then you know what you as an individual have to do. You know then that you have a responsibility.

What about the problem of people’s capacity to ignore suffering? We could say that 2 degrees of warming might cause 150 million people to die from air pollution,7 but the truth is so many of us already ignore so much human pain. Or let me put it this way: Climate activism has moved millions of people to action. How do you move millions more?

That is a very big problem. Since we are not being told these stories that are happening right now — the people whose lives are being lost and whose livelihoods are being taken away — we don’t realize they exist. Even if we are told, we feel as if they are too far away. It’s sad that for so long people in the most affected areas in the world have been fighting and saying these things but that it was only until our own children started saying, “We want a future” that people started caring. Where I’m from — and you as well — I’m sure people say: “We can’t take action because it’s too radical. It will cost too much. It will be too hard. We should be focusing on trying to keep ourselves safe and adapting.” Yes, we in this part of the world may be able to adapt for a while. We have the resources and infrastructure. But we forget that the majority of the world’s population don’t have that opportunity and won’t be able to adapt. They’re also the ones who are going to be hit hardest and first and are least responsible. That is being ignored to a degree that is pathetic.

And yet there are the Australia wildfires, the California wildfires, severe climate events — all there for us to see. Is it that even more individuals have to experience cataclysmic events in order for them to take the climate crisis more seriously?

Many people say that. They say it’s not until it’s burning in our own backyard that we will start to act. But that’s not true. If you look at Australia, did they change? No. Look at California. Did they change? No. We have lost contact with nature so much that even when it’s burning right in front of us, we don’t care. We care more about this social system, this political system that we’ve built up.

The anger in your speeches is a huge part of what connects with people. Do you still feel angry?

I’ve never felt that angry. When I say: “How dare you? You have stolen my dreams and my childhood”8 — that doesn’t mean anything. It’s a speech. When I wrote it, I thought, OK, this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to speak in the United Nations General Assembly, and I need to make the most out of it. So that’s what I did, and I let emotions take control, so to speak. But I’m actually never angry. I can’t remember the last time I was angry.

Thunberg addressing the U.N. Climate Action Summit in 2019, with Secretary General António Guterres, far left, and other activists. Jason DeCrow/Associated Press

What’s your sense of what draws people to you?

The climate movement, our biggest strength is that this is a movement completely based on scientific consensus. We go straight to the facts. It’s not more complicated than that. I’m not the leader of any movements.

You’re the face of one.

Frankly I don’t understand why the media focuses so much on activists rather than the problem itself. It’s an easy bridge to the problem itself. It makes it easier if you put the face on it. It becomes easier for people to understand. So I do understand why they do it. I don’t understand why they do it to this extent. It becomes almost absurd how much this celebrity culture takes over. And also, the people who feel threatened by the climate crisis and feel their interests are at risk, they go after the activists. They go for the fire alarm rather than the fire because it occupies people’s minds. When Trump talks about me,9 then people talk about that conflict rather than the climate itself.

I believe you that your goal isn’t to be a leader, but what is it that you want people to take from a film about you?

I hope it can be a bridge for people to understand that we are in a crisis. I would maybe like it if the movie was less focused on me and more focused on the science. But I understand that it’s a movie. Also, by doing this film, they show how absurd this celebrity culture we live in is, that people are so obsessed about me as an individual and an activist rather than the climate itself. And also that all this responsibility falls on us children and instead of taking action themselves people applaud children. Children who don’t even want to do these things but feel as if they have to because the people applauding aren’t.

Can I ask one more silly question?

Yeah.

This goes back to what you said about knowing how to communicate: What do you think is the specific quality of your communication that moves people? Is it a kind of wisdom?

I don’t think I have any specific wisdom. I don’t have much life experience. One thing that I do have is the childlike and naïve way of seeing things. We tend to overthink things. Sometimes the simple answer is, it is not sustainable to live like this.

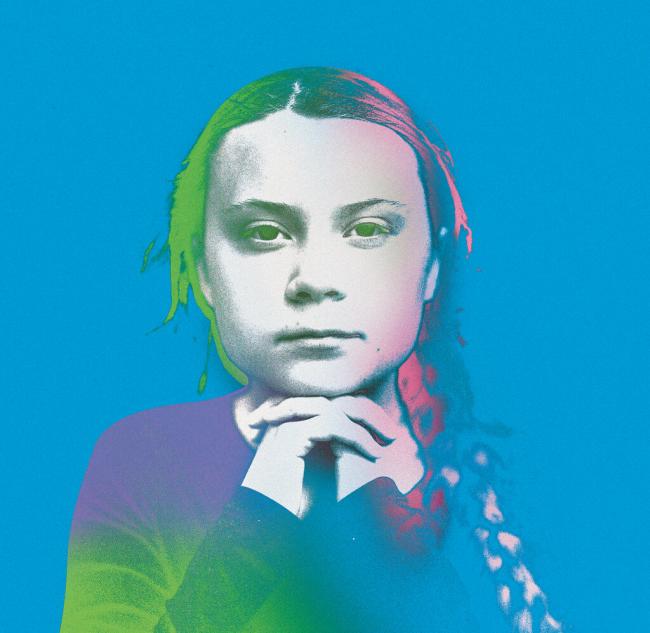

Photo illustration by Bráulio Amado. Opening illustration: Source photograph by Michael Campanella/Getty Images

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity from two conversations.