Articles Menu

Five days after wildfire destroyed the town of Lytton in British Columbia killing two people and injuring several others, officials were still trying to account for some residents who were missing. No one apparently saw the fire coming. When they saw smoke, according to Mayor Jan Polderman, it took all of 15 minutes before the whole town was ablaze.

This was the third time in five years during Premier John Horgan’s time on the job in which catastrophic fires have taken their toll. “I cannot stress enough how extreme the fire risk is at this time in every part of British Columbia,” he said the day after the evacuation. “This is not how we usually roll in a temperate rainforest.”

Lytton is actually located in the drier, fire-prone montane forest which dominates most of the interior of B.C. Contrary to what Horgan said, this is exactly how things have been rolling since at least 2003 when more than 45,000 people were evacuated from Kelowna and Kamloops as fires tore through thick stands of forests filled with ponderosa and lodgepole pine, Douglas fir and Sitka spruce. Some of these tree species need to burn because heat from a fire is the most effective way of opening up enough cones to release the seeds they hold. Others like the Douglas fir can regenerate without fire, but their seedlings do best in areas opened up by fire.

Hotter hells

The year 2003 was notable not for the amount of forest that was consumed, but for the number of people in the West who were in harm’s way. Twenty-five fires that burned 13 per cent of Glacier National Park along the Alberta-Montana border that summer sent bus and car tourists packing so quickly that those who were eating at a historic lodge didn’t have time to finish their meals. Two thousand people in Crowsnest Pass along the Alberta-B.C. border spent a good part of their day watching the fires from a place that was not their home. Jasper National Park burned big and scary enough that officials feared it might spread to the towns of Jasper and Hinton.

Banff would have burned bigger and possibly historically had wildfire managers fighting a fire in neighbouring Kootenay National Park not thrown away the playbook and lit a backfire that stopped it before the fire jumped into Banff. Parks Canada firefighters named it the “Holy Shit Fire” because that’s how a slew of senior government bureaucrats reacted when they were flown in to have a look at it.

What I remember most about Kootenay when I was there was Parks Canada’s Rob Walker telling me that this was a harbinger of future fires in rapidly warming landscapes. Walker was the fire and vegetation specialist in Kootenay. He had never seen a fire behave the way this one did. Young stands of aspen that are typically slow to burn literally vaporized as the hot wall of flames passed through them. Instead of slowing down in the coolness of the night, the fires kept chugging along like a freight train going down the tracks.

There have been a lot of things at play that have made the fire situation much more volatile since 2003. Suppressing fire so successfully as we have done for more than a century has shifted the balance away from young, mixed forests that are resilient to fire to older forests that are much more likely to ignite and burn intensely. Draining wetlands that can stop or slow a fire has made things worse.

Fire comes to town

Low property values and the allure of rural life have enticed retirees and other people from big cities to move into these dewatered, forested environments. Many of these newcomers built homes out of cedar and surrounded them with wooden fences and highly flammable ornamentals plants. To suppress the growth of unwanted vegetation, they laid bark around them. Some spend their work days or weekends in the forest on quads that have exhaust systems that can get hot enough to start a fire. Trains they hear at night occasionally shoot sparks into the dry vegetation along the tracks.

Even if they wanted to, most rural communities, especially those inhabited by Indigenous people, do not have the tax base to manage the vegetation in and around town as more affluent communities such as Banff and Jasper do with the federal funding that comes with being located in a national park. This is one of the reasons why First Nations communities such as Lytton account for 40 per cent of the evacuations in Canada. Their welfare is treated with less importance than those of tourists who spend big money in national parks.

And then there’s climate change which has been warming temperatures, producing more lightning and igniting fires at rates spreading with speeds and intensities that are unprecedented. This is not the “new normal” as fire scientist Mike Flannigan likes to say in correcting the media. There is nothing normal about what is happening.

Prior to the fire, Lytton was baking in temperatures close to 50 C for three days straight. That’s five degrees shy of the world record set in the Furnace Creek area of Death Valley last year. The big difference between Death Valley and Lytton is that Death Valley has few trees to speak of because of 12,000 years of gradual warming that has transformed it from a wetland fed by melting glaciers to a desert where most of the springs and ephemeral streams are sustained by 8,000 to 12,000 year-old fossil water that is still trickling underground from those long gone glaciers. Some relics of the past, such as pupfish, have hung on, but just barely.

Fifty degrees is a nightmare for firefighters. Even with temperatures in the mid-30s, the downdraft coming from water being dropped from a helicopter on a smoldering fire can bring the flames back to life. That’s what happened in Banff in 2003 when Pat Langan, a Parks Canada firefighter, was on the scene to witness it. “It was outrageous fire behaviour,” he told me. “It was like we poured a bucket of gasoline on it.”

Recognizing the explosive nature of the situation, Langan took the expensive measure of calling in an air tanker to drop some fire retardants on the fire. It’s a standard operating procedure that has been in play for decades. “Hit it hard, hit it fast. And keep it small.”

It was an effective strategy at the time. But fire is no longer behaving in ways in which it can be controlled with the traditional tools that firefighters have at hand. Many of these fires have become meteorological events that cannot be stopped. Once the fire reaches the size of a football field, as Flannigan likes to say, “the horse is out of the barn.”

Wildfires making wild weather

Consider the 2017 Kenow fire in Waterton Lakes National Park that sped from one end of the park to the other — equal to the north-south distance of Salt Spring Island — in less than eight hours, burning half the vegetated area of the park, 75 per cent of it with extreme severity.

Or the fire tornado. Scientists were initially in denial when word came that the Canberra fires of 2003 triggered a twister. It took nine years for scientists to prove that there was enough energy in that fire to spawn a category F-2 tornado.

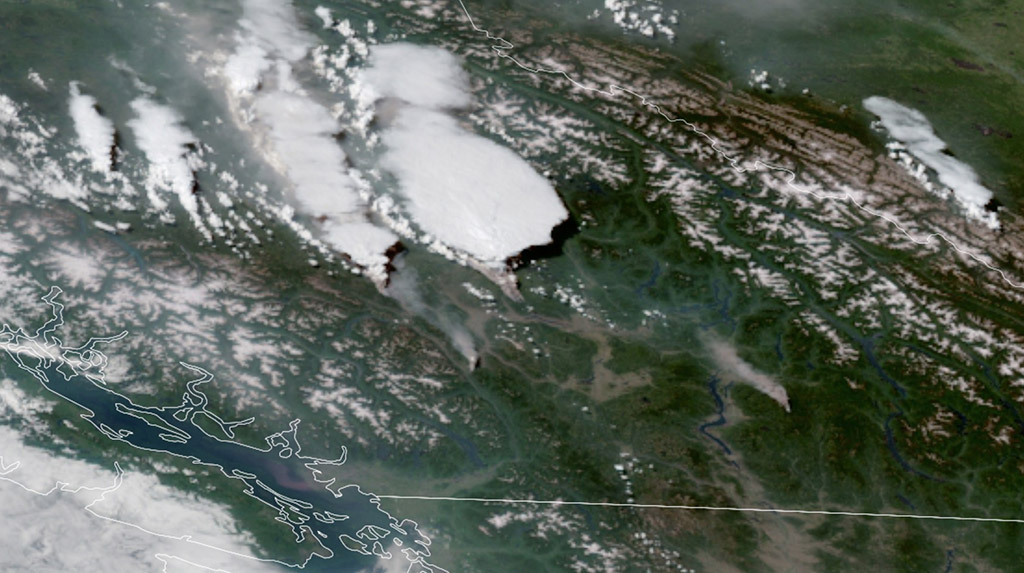

Then there are pyrocumulonimbus, or pyroCbs — fire-induced thunderstorms that create their own lightning. The chaos brought on by power of a pyroCb was on exquisite display in May 2016 when a wildfire ignited on the edge of the town of Fort McMurray, the oilsands capital of the world.

On that blue sky day, super-heated updrafts from the fire sucked smoke, ash, burning materials and water vapor high into the sky, where it began to cool and form “fire clouds” that look and act like those associated with a classic thunderstorm. The heat and particulates in the smoke triggered a dynamic reaction that arrested the ability of the cloud to produce precipitation. What was then left was a lightning storm that moved across the surrounding landscape, triggering a cluster of fires 40 kilometres ahead of the main fire front. No one had seen anything like that. And as one firefighter told me, “How the fuck do you deal with that?”

The realization that fires could create such fire-raining weather is fairly new. Scientist Mike Fromm had a hard time convincing colleagues that an aerosol cloud that he detected in the stratosphere in 2001 might have come from the Chisholm fire in Alberta, which was one of the hottest fires on record up until that time. Colleagues at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory insisted that the cloud must have come from volcanic eruptions because, like everyone else in the scientific community, they believed that pyroCbs didn’t have the energy to get past the troposphere, which contains most of the Earth’s atmosphere and where weather is generated.

There was, however, just one problem. Fromm could find no documentation of a volcanic eruption anywhere in the world to account for that cloud.

In Canada, the U.S., Russia, Australia and Europe, proof of the power of pyroCbs has mounted as the planet has continued to heat up. Firefighters thought they had seen everything until 2017 when five fire-driven thunderstorms rose up from the Chezacut fire in B.C., shooting black smoke and carbon high into the lower stratosphere, spewing noxious gases that were eventually detected almost as far north as the North Pole, and touching off more fires. The record that it set for pyroCbs didn’t last long. The Australian Black Summer bushfires of 2019-2020 produced at least 29.

On June 30, 710,000 lightning pulses and strokes were recorded in British Columbia and western Alberta during a 15-hour period when temperature records were being broken. It’s unclear how many of them were strikes that may have triggered fires, but we do know that a slow moving thunderstorm in Alaska in 2015 shot out 62,000 lightning strikes in five days, triggering 286 fires.

If there’s a lesson to be learned from all of this, it’s that the wildfire situation in Canada is heading in the same direction that it has been going in California, Australia, northern Russia and other parts of the world, including Greenland, which has burned twice in the past four years. Most people don’t appreciate that California didn’t have a serious wildfire problem before 2003 or that there were just two minor pryoCbs in Australia between 1978 and 2001 and 56 significant ones from 2001 to 2016.

Time to heed past warnings

It’s not like we haven’t been warned that that the fire situation was going to ramp up. In 1991, Mike Flannigan and Charlie Van Wagner published a paper predicting a near 50-per-cent increase in seasonal fire severity with a doubling of CO2 emissions. Former Manitoba premier Gary Filmon underscored this when, following the 2003 fire season, he was hired to produce a report on what could be done to limit or reduce the threat of fire. The Tyee’s headline at the time: “How BC Was Built to Burn.” Most of the recommendations were ignored.

Scientists were exasperated by this lack of action. When Flannigan and 70 other scientists gathered in Victoria in 2009 to address the issue of climate change and the impact it would have on the fire situation, he bluntly stated: “We’re exceeding thresholds all the time. We better start acting soon.”

“We let 150 wildfires burn each year and we need to be more transparent about that,” said Judi Beck, then the manager of fire management for BC Wildfire Management Branch. ″The public needs to know what we can and can’t do.″

Gordon Miller, a director general with the Canadian Forest Service, summed it up succinctly, saying, ″More fires mean more communities will be at risk.”

Progress has been made. Many communities have become more resilient with the help of the FireSmart program. Last year, the Canadian government invested $5 million towards the development of a wildland fire research network in Canada in collaboration with the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council. It was part of bigger plan to develop 68 wildland fire professionals at the graduate and postgraduate level. And just this June, the B.C. government announced that it is investing $5 million in a new research chair at Thompson Rivers University that will address the challenge of predicting when and where wildfire will arise and how it will spread.

But B.C.’s win in recruiting Mike Flannigan to fill the chair is Alberta’s loss. Flannigan headed up the Canadian Partnership for Wildland Fire Science at the University of Alberta, and given the extraordinary cutbacks there — 1,050 jobs to be eliminated — he is unlikely to be replaced.

Those who lost their homes, businesses and public services in Lytton will likely be compensated by insurance companies and governments, just as the people in Fort McMurray were following the 2016 fire. The total cost of that wildfire was, according to one study, $8.86 billion.

A fraction of that amount would go a long way to reducing the threat of fire if it was invested in making communities more resilient, in investing more in fire science, in the new tools that firefighters need to deal with wildfire, and ways in which Canadians can decarbonize. The fact that the people of Lytton had only 15 minutes notice of a wildfire that was about to destroy their town suggests that we haven’t learned a lot since 2003.

We would do well to learn quickly because we can expect ever more deadly lessons. As more people migrate into rapidly warming forested environments, we will need stricter building codes and better early warning and evacuation systems. We must recognize that fires are here to stay because we are now living in an era of pyroCbs, fire tornados and slow-moving thunderstorms that produce little rain but a great deal of lightning.

Historian Stephen J. Pyne has offered a name for this new era, which he ascribes to our fossil fuel burning and our willful suppression of good fires that are necessary for forests to regenerate. We may well have entered, he says, a “runaway fire age.” ![]()