Articles Menu

Oct. 26, 2021

Gerrit Biert's feet have never been so warm. Leaning out of his doorway to point out new gas-free construction in his village, he keeps them planted inside. "It's wonderful," he says of his low-carbon underfloor heating, a recent addition in his rented house. "And completely off-grid."

A housing company tore down then rebuilt his home last year as part of a larger project on several streets in the village of Loppersum in Groningen, a northern province in the Netherlands. Biert is especially proud that the rebuild has allowed him to come off the natural gas network. "I have nothing to do with gas anymore," he says.

The effort to disconnect from fossil fuels in Loppersum is noteworthy, given its location. The village sits atop the largest deposit of methane, or natural gas, in Europe. The giant reservoir stretches under almost the entire province of Groningen and has fed the country's gas boilers, electricity plants and heavy industries since the 1960s. But eventually the extraction caused the ground beneath the province to sink. As a result, earthquakes have increased in force and frequency across the north in the last few decades, damaging many of the homes.

"We have three earthquakes in a day sometimes," says Fanny Flikkema, 41, a long-time resident. "They can wake you up at night, and you have to check for new cracks in the walls." In Groningen, reinforcing homes to be building earthquake-resistant is expensive, and it is cheaper to build new resilient homes from scratch. On the plus side, this gives them the opportunity to go aardgasvrij, or free of natural gas.

Houses right on top of the gas field going gas-free seems like a clear sign the heat transition has arrived in the Netherlands. The nation is among many starting a drastic shift to low or zero-carbon alternatives to fossil fuels for heating homes. The Netherlands has among the lowest share of renewables in its total energy use in Europe: this transition will mean a complete overhaul of its heating system. With some of the most ambitious climate targets for its residential heating sector, the nation is now hoping to set itself up as a climate frontrunner in this area. At the heart of the heat transition debate is the question: what can replace the gas boiler?

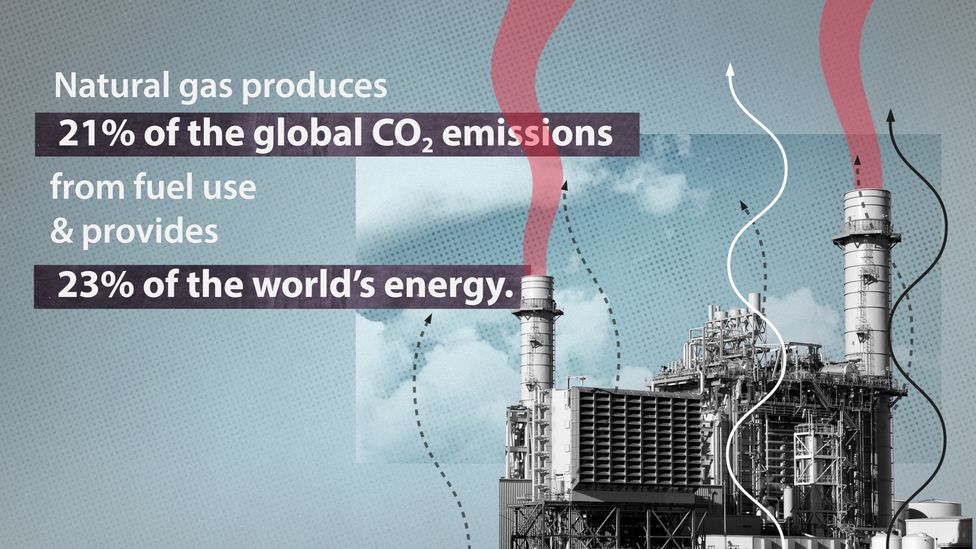

More than one-fifth of the world's CO2 emissions come from natural gas (Source: Our World In Data/Global Carbon Project, Credit: Adam Proctor/BBC)

In the Netherlands, the rising outcry over the danger of earthquakes from Groningen sealed the decision in 2019 to close the gas field eight years earlier than the scheduled closure date of 2030. Out in the cornfields and grass pastures, the 350 or so wellheads will go dormant by 2022. A small number will remain on standby for a few years, with extraction at a minimum, just in case the stores are called upon in a severe winter.

There is hope that these pilots will show the country how to meet its goal of getting every house off fossil fuels by 2050. All 8 million of them.

Communities across the country are now faced with deciding what to replace this natural gas with. Loppersum village is one of 50 "natural gas-free districts" who are piloting alternative low-carbon technologies, supported by €400m ($460m/£340m) in government funding up to 2030. With the government's initial goal of converting 50,000 houses by 2028, the government hopes that these pilots will show the country how to meet its goal of getting every house off fossil fuels by 2050. All 8 million of them.

It will be an immense shift, says Casper Tigchelaar, senior researcher on energy in the built environment at the Dutch Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO). "Five years ago this kind of scenario was just a hypothetical."

The Netherlands has a near-total dependence on gas as its energy source for heat. According to the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics, 92% of households use the gas for heating, making it the only country in Europe with proportionately more gas-connected houses than the UK. With domestic gas production dropping, the Netherlands is relying more and more on imported gas. As of 2018, the country was already a net importer. In fact, due to a decrease in coal use, the country's overall consumption of gas has not yet fallen significantly.

However, the country has proposed a raft of ambitious heat policies under its 2019 Climate Act, which aims to achieve an overall 49% reduction in CO2 emissions across its economy by 2030 compared with 1990 levels. At the moment, 38% of energy consumed in the Netherlands is used to heat buildings, with half of this going to homes. The government ruled in 2018 that all new houses must not be connected to the gas grid, starting that same year. By 2030, 1.5 million existing homes must have changed their heat source. And all buildings in the Netherlands must be using a low-carbon alternative to fossil fuels by 2050.

The scale of the challenge is immense. Since the Climate Act was introduced, fewer than 10,000 houses have been renovated to become carbon-free. "To meet these goals we would have to speed up the rate to 200,000 carbon-free renovations per year," says Tigchelaar.

Unlike other countries such as the UK, which has more centralised policies, the onus is on each of the Netherlands' 355 local municipalities to decide which type of heat to use. All are required to devise their heat transition plans by the end of this year. "This is a new task for us," says Anne Marie van Osch, project manager for sustainable energy for the municipality of Almere. "We have to learn about all of these technologies and seek them out for the communities." With much debate around which technologies are the best option, these are not always easy decisions.

For households that are well insulated and which would be tricky to connect to a wider heat grid, an individual heat pump might be the answer. Heat pumps work like a reverse air conditioner, transferring heat from outdoors to indoors via a refrigerant flowing through an internal loop. The heat can be released in the house in different ways, such as warm water in radiators, underfloor heating or warm air in the home. They use electrical energy, which can come from the grid or – even better – from solar panels, but they are up to four times more efficient than a gas boiler. Through energy savings, they tend to pay back their cost over a period of years.

"I'm excited to get it working for the first time this winter," says Boudewijn Wiersma, who owns one of the first heat pumps to be installed in Paddepoel, a suburb of Groningen city. The pump is nested in the garden of his home, which was renovated by an EU funded project called Making City. "We wanted to demonstrate heat pumps work with real people living inside," says Els Struiving, coordinator for the demo-houses in Paddepoel who organises open house evenings for local residents to see the tech at work.

There's a downside to heat pumps, though. "They're expensive," says Wiersma. "Without the grant I couldn't have paid for it." Depending on the type, a heat pump and its installation costs from €6,000-20,000 ($7,000-23,200/£5,000-16,800). According to Tigchelaar, the cost of heat pumps needs to drop for them to become a widespread solution in the Netherlands, "or more subsidies made available for households". Cheaper, hybrid solutions, which combine heat pumps and natural gas, are now being discussed as a more feasible option than all-electric heat pumps.

In some quarters, hydrogen is also a talking point as a fossil fuel alternative. In the rural village of Valthe, in the north-eastern Drenthe province, a group of engineers are showcasing a "tiny hydrogen house" which travelled here on the back of a lorry. It smells of sawn timber and, thanks to the food truck opposite, hot chips and maatjes – fresh herring sandwiches. There's a fairground feel as residents roll up to see the new invention.

Hydrogen provides both electricity and heat to the house. The main attraction is a coveted product around the back: a small electrolyser. By virtue of solar panels on the roof, the electrolyser splits water into hydrogen and oxygen via an electric current. The hydrogen gas can then be burned for heat in a special boiler.

"The house shows on a mini scale what you could do for towns," says Remco de Vries, a renewable energy specialist who designed the system. Inside, it's a cosy bungalow with a working kitchen and a sitting room. "Can I just live here?" asks one resident.

Outside, Renske Bouden, a Valthe resident, is explaining the village's plan to buy a hydrogen electrolyser and power it with a field of solar panels. "We actually get a lot of sun here," she says.

It's an unusual scheme given the government has cautioned hydrogen will likely only become affordable and widely available after 2030. But Bouden argues that rural homes are not energy efficient enough for individual heat pumps, and are too far apart to make it worth putting a heat network in the ground. "With all the gas infrastructure in the village already, it would be more efficient to convert it to hydrogen," she says. Twenty miles (32km) to the west of the village, the Hoogeven municipality is already constructing an all-hydrogen neighbourhood, to be ready by 2023.

But Marjan Minnesma, founder of the Urgenda Foundation – a Dutch environmental group which has become a household name after taking the state to court over its climate commitments – warns that hydrogen is not a silver bullet for residences. As hydrogen will be needed to decarbonise industrial processes like steelmaking due to the high temperatures it can provide, homes should use limited amounts of the gas, and only when there is no other option, says Minnesma. "The government focus should be on renewable electrification with heat pumps," she says. "District heating, by different methods, could provide the rest."

The Netherlands has in fact already set its sights on district heating, which funnels heat from a large, single source to many homes via an underground network of pipes. The system has proven an energy efficient option in countries such as Denmark, where two-thirds of homes are part of heat networks. An analysis by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency estimates that a quarter of homes will be connected to heat networks by 2030, up from around 5% currently. Because heat grids require digging up the roads and laying heat pipes between houses, they will be most effective in urban, densely populated areas.

Cutting methane emissions from fossil fuel extraction could be an easy win for the climate (Credit: Adam Proctor/BBC, source: International Energy Agency)

Some districts plan to drill for this heat. In Maasland, a town in the west of the country near the banks of the Rotte river, densely packed greenhouses stretch from horizon to horizon, steamed up with heat. Such vistas are behind the Netherland's position as the second largest agriculture exporter in the world after the United States, and they demand a lot of heat energy.

The greenhouses in Maasland are heated carbon-free. In the southern corner of the complex is a geothermal well, pumping up 90C hot water from underground. "With every kilometre down you get around 30C of heat warmer," says Danny van den Berg, policy advisor at Geothermie Nederland. At 3km deep, this one has enough heat up for all the greenhouses for 7km around.

It uses a simple process, similar to a household heat pump. The hot water is pumped up from an outdoor well and channelled through a large mattress-shaped bit of kit – the heat transfer – which is filled with alternating plates. The transfer acts like two interlocking radiators: the hot geothermal plates heat up a circuit of cooler fresh-water plates. The heated fresh water is then fed into the network of greenhouses, while the geothermal water is pumped back underground.

The geothermal industry believes the technology has massive potential for homes across the country, which currently use little geothermal energy. "One well like this could heat 3,000 to 4,000 homes," says van den Berg.

In 2018 the geothermal industry created a masterplan, claiming it could meet 7% of residential heat needs by 2030, and 35% by 2050. Hans Bolscher, chairman of Geothermie Nederland, says the largest hurdles are finding the needed investment and the planning that needs to take place on a local level.

But there are also other sources of energy for district heating. Amsterdam, which is ringed by a conurbation of data centres, could be an interesting case. Hundreds of rooms lined with blinking servers combine processing power to make it one of the largest internet exchanges in the world. They also create a considerable amount of heat, says van Osch, from the neighbouring municipality of Almere. But there's currently no infrastructure connecting them to nearby houses.

In Amsterdam's heat transition vision the municipality estimates that as much as 2.2 million kilowatt hours – around 30% of the city's heat demand – could be generated by data centres.

The burning of vegetation in biomass plants is another source of district heating that is being explored, but this presents its own complications. Though currently responsible for 60% of the country's renewable energy, debate among policymakers about the sustainability of burning forest biomass for energy have resulted in a freeze on new subsidies for the technology.

The Netherlands' Climate Act stands apart from other countries' climate laws when it comes to the role of the local municipalities. The accord puts the districts in charge of choosing their heating system, with participation a key tenet of the final accord. "It's new for the municipalities," says Tigchelaar. "Sourcing their energy supply was not something they were previously involved in."

Els Stuiving, founder of a prospective local energy cooperative in Paddepoel, believes the challenge of asking residents to change their heat source is as much a social issue as it is a climate or technological one. "Imagine if someone knocked on your door and told you that your district is going to dig up the road and replace your heating with something new," says Stuiving. "You'd probably have a few questions."

A failure to achieve local consensus and support is leading some of the gas-free pilot neighbourhoods to fall behind its schedule of 50,000 dwellings by several thousand households. The lag has led to debate about whether district heating should be made obligatory. But this is not the only option, says Tigchelaar. "You can start with more financial support and subsidies. At the moment none of the options are competitive enough against natural gas."

Around 7% households in the Netherlands, around 550,000 homes, live in energy poverty. Rising gas prices increase this to 9% – an additional 150,000 households. "A big question for the district approach is how we can help people who simply cannot afford to invest in their homes," says Tigchelaar. "Insulation, particularly, must be made cheaper and available to people who need it via subsidies. Low-income households need to be better considered in the transition plans." But he believes the pilot projects have been valuable, despite the delays. "The living labs show us what is working and what isn't," he says.

These pilots bring a sense that previously abstract climate targets are now meeting the bricks-and-mortar reality of peoples' homes and lifestyles. "It's vital that it's done in a way that improves residents' quality of life," says Struiving. "For the transition to happen, you need to bring everybody with you."

--

Data research and visualisation by Kajsa Rosenblad

Animation by Adam Proctor

--

Towards Net Zero

Since signing the Paris Agreement, how are countries performing on their climate pledges? Towards Net Zero analyses nine countries on their progress, major climate challenges and their lessons for the rest of the world in cutting emissions.

--

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.