Articles Menu

Dec. 4, 2023

Adapted from Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto copyright © 2020 by Kōhei Saitō. Translation copyright © 2024 by Brian Bergstrom. Published by Astra House. All rights reserved.

What kinds of measures are you taking, personally, to prevent global warming? Have you bought a reusable shopping bag to reduce your reliance on disposable plastic ones? Do you carry a thermos so you don’t end up buying drinks in plastic bottles? Did you buy an electric car?

Simply thinking that such actions are effective countermeasures can prevent us from taking part in the larger actions that are actually necessary to combat climate change. They function like Catholic indulgences, allowing us to escape the pangs of our conscience via consumerism and to look away from the danger around us, allowing the forces of capital to swaddle our concerns in environmental impact statements and tuck them away beneath the form of deception known as greenwashing.

Long ago, Karl Marx characterized religion as “the opiate of the masses,” because he saw it as offering temporary relief from the painful reality brought about by capitalism. The Green New Deal is a contemporary version of the same opiate.

The reality that must be faced—that must not be fled from into the arms of a comforting opiate—is that we humans have changed the nature of the earth in ways that are fundamental and irrevocable.

Before the Industrial Revolution, the density of atmospheric carbon dioxide was around 280 parts per million, while by 2016 the level had passed 400 ppm even at the South Pole. This was the first time these levels had been reached in 4 million years. And they are being exceeded more every day, even as you read this. Four million years ago, the ice shelves of Antarctica and Greenland were completely melted, and some 20 feet higher than today’s. It seems clear that human civilization is facing a threat to its very existence.

Coddled by the invisibility of our lifestyle’s costs, those of us living in the Global North have been able to turn our back on reality, ignoring the inkling of awareness tickling the edges of our consciousness, and now we’ve run out of time to take measures to address the danger.

As we’ve procrastinated, the consequences of our lifestyle have become steadily more difficult to ignore. As the time left before we pass the point of no return shrinks to almost nothing, the possibility of implementing major, unprecedented policies at the governmental level is being debated around the world.

One plan that has inspired much hope and expectation is the Green New Deal. Prominent pundits in the United States like Paul Krugman, Thomas Friedman, and Jeremy Rifkin have called for its adoption. Politicians around the world, including Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Yanis Varoufakis, have run for office with a Green New Deal as part of their platforms.

The Green New Deal, broadly speaking, involves large-scale public spending and investment in the promotion of renewable energy and electric cars. By creating stable, high-paying employment and therefore greater effective demand, these measures are also meant to stimulate the economy. The expectation is that improved business conditions would lead to greater investment, which would spur the transition to a sustainable green economy.

This proposal reflects the wish for a return to the original New Deal that saved American capitalism after the Great Recession of the 20th Century. The current austerity regimes have proven unable to address the chronic outbreak of emergencies like pandemics, wars, and climate change. Now is the time for a new, environmental Keynesianism—a green Keynesianism—to take their place. Its active and expansionary fiscal policy aims to accelerate investments in green infrastructure.

But can such a lovely story be true? Can a Green New Deal really save us?

The truth is that the green Keynesianism embodied in these policy plans would indeed spur economic growth. The widespread adoption of solar panels, electric cars, and quick-charging batteries along with the development of biomass energy will lead to substantially increased financial investment and job creation.

But even if we decide to foster economic growth to counter climate change, there are limits we must not exceed in terms of the amount of additional environmental burden produced by the great transition to a sustainable economy. This is the opinion of the environmentalist scholar Johan Rockström. He and his research team presented the concept of “planetary boundaries” in 2009.

The planetary system is supported by the innate resilience of nature. But if burdens above a certain magnitude are placed on this system, this resilience is lost, and the possibility arises that abrupt, irreversible, and destructive changes will occur, such as the melting of the polar ice caps or the mass extinction of plants and animals. These are known as tipping points. Perhaps it goes without saying, but passing these tipping points would spell disaster for humanity.

Rockström has defined the limits within which humanity can continue to enjoy a stable existence, mapping out the thresholds demarcating nine sectors of planetary resilience. The nine sectors are climate change, loss of biodiversity, biochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorous, land-system changes, freshwater use, ocean acidification, ozone layer depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading, and pollution by chemical substances.

These are the planetary boundaries. Rockström proposed a plan by which “humanity can continue to develop and thrive” in a stable manner as long as these boundaries are respected.

The problem is that according to Rockström’s calculations, four planetary boundaries, including climate change and loss of biodiversity, have already been exceeded due to human economic activity.

I especially want to draw attention to one of Rockström’s newspaper articles, which he published in 2019. The title of this article is provocative: “Green Growth is Wishful Thinking: We Must Act.”

Until then, Rockström had, like many of his fellow researchers, argued that the goal of keeping global temperatures from rising less than 1.5° C was reachable if a version of “green economic growth” was put in place that remained within the planetary boundaries he’d defined. In this article, however, that optimism has vanished. Instead, he argues that the public must choose between two mutually exclusive actions: continued economic growth or reaching the goal of keeping global temperatures from rising more than 1.5° C. To put it in slightly more technical language, Rockström concludes that decoupling economic growth, even when adjusted to meet the 1.5° C target, and the environmental burdens of such growth is, in reality, extremely difficult.

Decoupling might be a word seldom encountered in daily life, but it’s a term used widely in both economics and environmentalism.

Normally, economic growth increases burdens on the environment. Decoupling is the attempt, through new technologies, to sever the link between economic growth and increases in environmental burden. In other words, it’s an effort to find ways to grow the economy without worsening the impact of that growth on the environment. In the case of climate change, this means developing technologies that would support economic growth while reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

For example, manufacturing cars, building housing, and creating infrastructure like power plants and grids stimulates economic growth, but it also leads to huge increases in carbon-dioxide emissions. But if countries are able to support this development by adopting more efficient new technologies, the volume of carbon-dioxide emissions will rise in a gentler curve than if this infrastructural shift and large-scale consumption occurred while relying on old technology. The classic form this takes is the introduction of energy-saving technologies, hybrid cars, natural gas power generation, and the like.

Lessening the increase in carbon-dioxide emissions relative to what would normally accompany increased economic growth by optimizing technological efficiency is referred to as relative decoupling.

Relative decoupling is, unfortunately, woefully inadequate as a measure to combat climate change. The rise in global temperatures cannot be curbed unless carbon-dioxide emissions are reduced absolutely, not relatively. The attempt to grow economically while reducing absolute emissions of carbon dioxide is known as absolute decoupling.

One example of absolute decoupling is the widespread adoption of electric cars, which emit no carbon dioxide at all. As the number of petrol-burning cars decreases, so does the amount of carbon-dioxide emissions, while the sale of electric cars allows economic growth to continue.

Another example of absolute decoupling would be conducting business meetings online via telecommunications technology rather than requiring people to board aeroplanes and attend in person. The shift from fossil fuel power generation to solar power would also be an example of this: growth continuing even as emissions decrease. By combining multiple measures of this sort, it would become possible for the economy to grow while carbon dioxide emissions decrease in absolute, not relative, terms.

One can easily see how the technologies associated with relative decoupling differ from those associated with absolute decoupling. Furthermore, the technologies that would enable absolute decoupling have yet to be widely adopted throughout society. This is precisely why their adoption requires large-scale investment and also why they represent such a golden opportunity for fostering economic growth.

In this way, the Green New Deal aims to reduce absolute carbon dioxide emissions to zero and keep global temperatures from rising more than 1.5° C while allowing the GDP to grow in the manner it always has. Of course, this would necessitate a correspondingly large-scale technological revolution. The Green New Deal is this century’s grandest project to bring this about, and thus effect an absolute decoupling of economic growth and environmental damage.

But will bringing about absolute decoupling really be so easy?

To answer this, the question quickly changes to: When will we be able to fully convert to a carbon-free society? It seems possible to do this, and thus reach the zero-emissions goal, within the next 100 years.

But by then it will be too late. We need to remember the warnings of scientists—that we need to reduce emissions by half by 2030, and to zero by 2050. In other words, humanity’s destiny lies in whether we will be able to effect sufficient absolute decoupling to stop climate change within the next 10 to 20 years.

At this point, even someone like Rockström has accepted that the idea of fostering green economic growth through decoupling is nothing more than “wishful thinking.” It’s impossible to effect an absolute decoupling of sufficient scale to reach the goal of keeping global temperature rises below the 1.5° C mark.

But why is it impossible? The answer lies in the simple yet intractable dilemma that haunts any decoupling attempt. The dilemma is this: As the economy grows, the range of human economic activity grows too, which means that the volume of resource and energy consumption will also grow, making it difficult to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. This is a historical tendency.

In other words, even green economic growth may cause increases in carbon emissions and resource use in direct proportion to its success because economic growth is historically accompanied by more frequent consumption of bigger commodities, including ones in wasteful and carbon-intensive industries. This in turn will necessitate more and more dramatic increases in efficiency, but there is an insurmountable physical limit to the improvement of technological efficiency. This is the Growth Trap, a major pitfall awaiting capitalism as it attempts to establish a zero-carbon economy. The question is, can this trap be avoided?

Unfortunately, escaping this trap is unlikely. Sustaining a growth rate of 2–3 percent for the GDP would necessitate the immediate reduction of carbon dioxide emissions by 10 percent every year to hit the 1.5° C target. If we leave it to the market, the likelihood of achieving a yearly reduction rate as dramatic as 10 percent or more is very low.

Rockström states that once we face the Growth Trap directly, the natural choice that comes to the fore is giving up on economic growth. The reason is simple: If we give up on growth and allow the scope of the economy to contract, reaching our carbon-dioxide emission reduction goals will become easier.

This is the one decision we must make if we want to halt the destruction of the global environment and sustain the conditions necessary for humanity to thrive. But it’s a decision that cannot be made under capitalism. Here we encounter another of capitalism’s traps, the Productivity Trap.

Capitalism is always trying to raise workforce productivity in order to cut costs. Rises in workforce productivity allow the same amount of production to occur with fewer workers. When this happens, the economy’s size remains constant while unemployment rates rise. But capitalism also makes it impossible for the unemployed to live, and politicians hate high unemployment rates. For this reason, there’s a huge amount of pressure for the economy to keep expanding indefinitely so as to maintain the rate of employment. This is why a rise in productivity results in the expansion of the economy. This is the Productivity Trap.

Capitalism cannot escape the Productivity Trap, which means it cannot wean itself off its dependence on economic growth. This is why even if we were to put in place measures to combat climate change, we would end up falling into the Growth Trap, resulting in further increases in resource consumption.

Fundamentally, no matter how much technology may advance, efficiency and optimization have physical and thermodynamic limits. No matter how efficient things get, we will never be able to create cars using half the amount of resources we do now, on top of the fact that creating storage batteries and electric cars takes energy as well.

As a quick look back over the history of capitalism since the Industrial Revolution tells us, economic growth during the 20th century was only possible using enormous amounts of fossil fuels. Economic growth and fossil fuel consumption are intimately linked, and thus fossil fuel cannot be replaced with green energy. It’s physically impossible to sustain the same level of economic growth as before and reduce carbon.

Taking this into account, it would be a mistake, in a time of climate crisis, to place our hopes on a form of economic growth dependent on absolute decoupling. This is precisely why “green growth” strategies for combating climate change, which spread the illusory notion that absolute decoupling is easily achievable, are so dangerous.

Whatever the case, the fact that wide-ranging, consistently applied decoupling is extremely difficult to bring about means that the promises made by green Keynesianism can never be kept. Even if politicians can win elections on grandiose platforms proclaiming Green New Deals, they will never be able to fulfil their promise to solve the environmental crisis. The problem has deeper roots than that.

This is why over 1,100 scientists issued a statement in 2019 stating that the “climate crisis is closely linked to excessive consumption of the wealthy lifestyle,” and called for the radical transformation of the mechanisms by which the present economy functions.

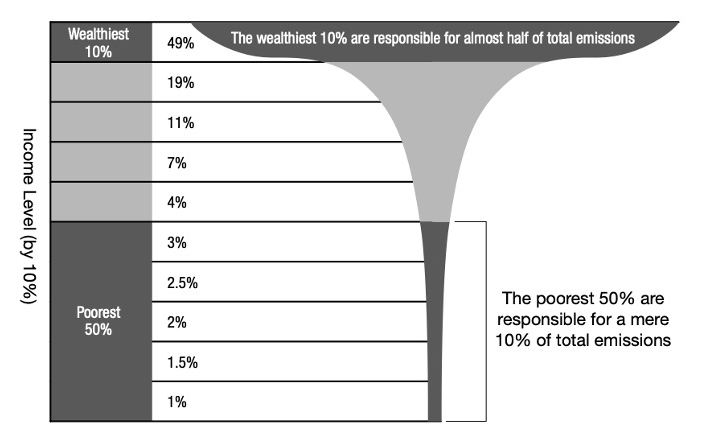

Of course, the “wealthy lifestyle” of which they speak is that of the rich populations of the Global North, who are responsible for an excessive proportion of carbon dioxide emissions. A shocking piece of data shows that the carbon dioxide emitted by the top 10 percent of the world’s richest people makes up half of worldwide emissions. The top 0.1 percent, especially, have an extremely serious impact on the environment as they drive around in sportscars, hop from place to place in private jets, and maintain multiple mansions.

On the other hand, the least wealthy half of the world’s population are responsible for a mere 10 percent of worldwide carbon dioxide emissions. Yet they are also the first to suffer from the effects of climate change. This is where we see the contradictions of the Imperial Mode of Living and the externalization society play out very clearly. And this is why it is perfectly appropriate to call for primarily the rich to reduce their emissions.

The fact is, if the world’s richest 10 percent were to lower the amount of emissions they produce to that of the average European, overall emissions would decrease by a full third. This would create sufficient time for a comprehensive transition to sustainable social infrastructure.

But we must also keep in mind the following: Almost every one of us living in a developed country belongs to the world’s richest 20 percent, and even some of those who call themselves “middle class” are actually part of the top 10 percent. In other words, it will be impossible to truly combat climate change if we all fail to participate, as directly interested parties, in the radical transformation of the Imperial Mode of Living.

The only way to avoid this trap is to disengage from a consumer culture that equates car ownership with independence, while also reducing the volume of everything we consume. We must make a major incision into capitalism itself to heal the world.

Make no mistake: Green New Deal–style governmental platforms enabling large-scale investment into remaking nations at a fundamental level are indispensable in the struggle to combat climate change. It’s undeniable that we must make the transition to solar energy, electric vehicles, and the like. Public transportation systems must be expanded and made free to all, bicycle lanes must be built, public housing fitted with solar panels must be created—these sorts of works projects, driven by public spending, are all vital.

But these things are not enough. It might sound counterintuitive, but the goal of any Green New Deal should not be economic growth but rather the slowing down of the economy. Measures to stop climate change cannot double as ways to further economic growth. Indeed, the less such measures aim to grow the economy, the higher the possibility they’ll work.

The only thing left to say about Green New Deal proposals aiming to promote unlimited economic growth at this point is, “The road to extinction is paved with good intentions.”

Kohei Saito is an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Tokyo and the author of Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto.

[Slow down: The Japanese philosopher Kohei Saito argues that is physically impossible to sustain high levels of economic growth and reduce carbon.(Eric Gaillard / Reuters Pictures)]