Articles Menu

From: Patrick Bond

Date: April 8, 2020 at 12:33:48 PM PDT

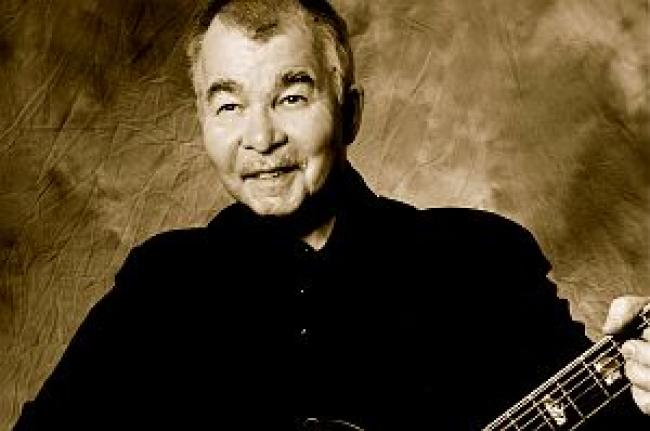

Subject: Thanks to musician John Prine - critic of King Coal in Kentucky; victim of Coronavirus

There's another Coronavirus victim from the world of progressive culture: singer John Prine, age 73. (Manu Dibango died last week; the Cameroonian Afro-Funk saxophonist was 86. Listen to his classic Soul Makassa here.)The Prine song Paradise about coal mining in Kentucky is stunning. Here's an excellent Prine original of Paradise that has the kind of rolling photos within the video, that puts you right there - and if not, the long article about the song may well. And here's a really great David Rovik rendition.

Prine's target was a coal mining company, Peabody, that used "the world's largest shovel." The U.S. government's Export-Import Bank pushed that same sort of shovel into South Africa in 2010-11 and our little protest in Washington didn't make a dent, as I was recalling below.

John Prine wrote the haunting song ‘Paradise’ about the strip-mining of his Kentucky homeland, with this verse describing a creature known as ‘Big Hog’:Then the coal company came with the world’s largest shovel

And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land

Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken

Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man.Big Hog was a Bucyrus-Erie 3850-B dragline shovel. With West Virginia coal companies no longer buying these monsters, the company is fanatical about overseas sales. As a result, last Thursday, two dozen of us gathered by Friends of the Earth and Sierra found ourselves shouting slogans against Eskom and Bucyrus outside the Ex-Im Bank’s Washington headquarters.

The Milwaukee corporation rebutted that Ex-Im financing was justifiable because of a Johannesburg Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) partner plus Wisconsin steelworkers jobs, even though this means that South African counterparts – especially a Joburg company, Rham, that will apparently fire scores of local employees – lose out. Bucyrus’s 2010 contract to supply Eskom with coal mining equipment became a scandal subject to a parliamentary investigation last September. Given the Witwatersrand area’s historical world leadership in mining equipment, businesses there claim there’s no obvious reason why local firms cannot supply Eskom at much lower cost (one third of Bucyrus’ in that particular case).

Most importantly, the poor will repay this finance at a time South Africa has become the world’s most unequal society and unemployment is raging.

Dethroning King Coal in 2011, from West Virginia to Durban

Posted on January 17, 2011, Climate & Capitalism

This multiple set of interlinked climate-energy-economic travesties can only be reversed by grassroots and labor activism

by Patrick Bond

South Africa’s crust was drill-pocked with abandon since Kimberley diamonds were found in 1867 and then Witwatersrand (Johannesburg) gold was unearthed in 1886. But the world’s interest in how we trash our environment perked up again last week for two reasons:

- the shocking revelation that acid mine drainage is now seeping into the Johannesburg region’s ‘Cradle of Humankind’, home of hominid fossils dating more than three million years, where our Australopithecus ancestors’ earliest bones are now threatened by the area’s pollution-intensive mining industry; and

- hot contestation of new United States financing for South Africa’s proposed Kusile power plant, which will be the world’s third largest coal-fired facility.

In parallel battles, though, the beheading of King Coal is underway in West Virginia, where nine days after the January 3 cancer death of heroic eco-warrior Judy Bonds, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) overturned the Army Corps of Engineers’ prior approval of Spruce No. 1 mine, the world’s largest-ever ‘mountaintop removal’ operation. Coal companies have been blowing up the once-rolling now-stumbling Appalachians. In order to rip out a ton of fossil fuel, they dump 16 tons of rubble into the adjoining valleys.

After an avalanche of pressure by mountain communities and environmentalists, the EPA ruled against the “unacceptable adverse effect on municipal water supplies, shellfish beds and fishery areas (including spawning and breeding areas), wildlife, or recreational areas.” According to leading US climatologist James Hansen, quoted in Bonds’ New York Times obituary last week, “There are many things we ought to do to deal with climate change, but stopping mountaintop-removal is the place to start. Coal contributes the most carbon dioxide of any energy source.” The EPA also took a stance in late December to belatedly begin regulating greenhouse gas emissions.

Through activism and legal strategies, US communities and the Sierra Club have prevented construction of 150 proposed coal-fired power plants over the last couple of years, a remarkable accomplishment (only a couple got through their net).

But in South Africa, the fight is just beginning. The national government in Pretoria and municipal officials in seaside Durban will continue invoking several myths in defense of coal, Kusile and the ‘COP17’, the November 28-December 9 climate summit officially called the ‘Conference of the Parties 17’ (but which should be renamed the Conference of Polluters). Here are some strategies of the SA state and big business meant to blind us:

- in Durban, aggressive ‘greenwashing’ will attempt to distract attention from vast CO2 emissions attributable to South Durban’s oft-exploding oil refineries and petrochemical complex, Africa’s largest port, the hyperactive tourism promotion strategy (in lieu of any bottom-up economic development), unending sports stadia construction and unnecessary new King Shaka international airport, electricity going to the very dangerous Assmang ferromanganese smelter (the city’s largest power guzzler by far at more than a half-million megawatt hours per year), sprawly new suburban developments, and inefficient electricity consumption and transport because of state failure to provide adequate renewable energy and mass transit incentives;

- ‘offsets’ for a tiny fraction of Durban’s emissions will again be fatuously marketed to an unsuspecting public, as during the 2010 World Cup, including mass planting of trees (though when they die the carbon is re-released) and municipal landfill methane capture – even though the increasingly-corrupt offset industry and European carbon markets which market our emissions credits are now ridiculed across the world, and in economic terms are failing beyond even the most pessimistic predictions;

- whacky, unworkable ‘geo-engineering’ strategies are going to multiply, such as biomass planting to convert valuable food land into fodder for ethanol fuel, or mass dumping of iron filings in the ocean to create carbon-sucking algae blooms, or ‘Carbon Capture and Sequestration/Storage’ schemes to pump power-plant CO2 underground but which tend to leak catastrophically and which require a third more coal to run, or the nuclear energy revival notwithstanding more shutdowns at the main plant, Koeberg (five years ago the industry minister, Alec Erwin, notoriously described as ‘sabotage’ a minor Koeberg accident that cost the ruling party its control of Cape Town in the subsequent municipal election); and

- South African ‘global climate leadership’ will be touted, even though Pretoria’s reactionary United Nations negotiating stance includes fronting for Washington’s much-condemned 2009 Copenhagen Accord, which even if implemented faithfully, by all accounts, will roast Africa with a projected temperature rise of 3.5°C.

As even the government’s new National Climate Change Response Green Paper admits, “Should multi-lateral international action not effectively limit the average global temperature increase to below at least 2°C above pre-industrial levels, the potential impacts on South Africa in the medium- to long-term are significant and potentially catastrophic.” The paper warns that under conservative assumptions, “after 2050, warming is projected to reach around 3-4°C along the coast, and 6-7°C in the interior” – which is, simply, non-survivable.

If President Jacob Zuma’s government really cared about climate and about his relatives in rural KwaZulu-Natal villages who are amongst those most adversely affected by worsening droughts and floods, then it would not only halt the $21 billion worth of electricity generators being built by state power company Eskom: Medupi is under construction and Kusile will begin soon. Pretoria would also deny approval to the forty new mines allegedly needed to supply the plants with coal, for just as at the Cradle of Humankind and in West Virginia, these mines will cause permanent contamination of rivers and water tables, increased mercury residues and global warming.

More evidence of the Witwatersrand’s degradation comes from tireless water campaigner Mariette Liefferink, who counts 270 tailings dams in a 400 square kilometer mining zone. With gold nearly depleted, as Liefferink told a Joburg paper last week, uranium is an eco-social activist target: “Nowhere in the world do you see these mountains of uranium and people living in and among them. You have people living on hazardous toxic waste and of course some areas are also high in radioactivity.”

The toxic tailings dams are typically unlined, unvegetated and unable to contain the mines’ prolific air, water and soil pollution. Other long-term anti-mining struggles continue in South African locales: against platinum in the Northwest and Limpopo provinces, against titanium on the Eastern Cape’s Wild Coast, and against coal in the area bordering Zimbabwe known as Mapungubwe where relics from a priceless ancient civilization will be destroyed unless mining is halted (as even the government agrees).

There’s another reason that the power of what is termed the Minerals-Energy Complex continues unchecked, even as treasures like the Cradle – and also the priceless Kruger Park’s surface water plus millions of people’s health – are threatened: political bribery. In addition to supplying the world’s cheapest power to BHP Billiton and Anglo American Corporation smelters by honoring dubious apartheid-era deals, Eskom’s coal-fired mega-plants will provide millions of dollars to African National Congress (ANC) party coffers through crony-capitalist relations with the Japanese firm Hitachi.

Last year, Pretoria’s own ombudsman termed the role of then Eskom chairman and ANC Finance Committee member Valli Moosa ‘improper’ in cutting the Hitachi deal. As a result, even pro-corporate Business Day newspaper joined more than 60 local civil society groups and 80 others around the world in formally denouncing $3.75 billion World Bank loan to Eskom which were granted by neoconservative-neoliberal Bank president Robert Zoellick last April.

Other beneficiaries of Washington’s upcoming trade finance package for Eskom include two desperate multinational corporations: Black & Veatch from Kansas and Bucyrus from Wisconsin. The latter showed its clout last October when in order to fund machinery exports to the huge Sasan coal-fired plant in India with US Export-Import Bank subsidies, the Milwaukee firm yanked members of Congress so hard that they in turn compelled the Bank to reverse an earlier decision not to fund Sasan on climate grounds.

But now, after the EPA’s slap-down of Spruce No. 1, Bucyrus must be really nervous. Forty years ago, John Prine wrote the haunting song ‘Paradise’ about the strip-mining of his Kentucky homeland, with this verse describing a creature known as ‘Big Hog’:

Then the coal company came with the world’s largest shovel

And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land

Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken

Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man.

Big Hog was a Bucyrus-Erie 3850-B dragline shovel. With West Virginia coal companies no longer buying these monsters, the company is fanatical about overseas sales. As a result, last Thursday, two dozen of us gathered by Friends of the Earth and Sierra found ourselves shouting slogans against Eskom and Bucyrus outside the Ex-Im Bank’s Washington headquarters.

The Milwaukee corporation rebutted that Ex-Im financing was justifiable because of a Johannesburg Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) partner plus Wisconsin steelworkers jobs, even though this means that South African counterparts – especially a Joburg company, Rham, that will apparently fire scores of local employees – lose out. Bucyrus’s 2010 contract to supply Eskom with coal mining equipment became a scandal subject to a parliamentary investigation last September. Given the Witwatersrand area’s historical world leadership in mining equipment, businesses there claim there’s no obvious reason why local firms cannot supply Eskom at much lower cost (one third of Bucyrus’ in that particular case).

Most importantly, the poor will repay this finance at a time South Africa has become the world’s most unequal society and unemployment is raging. For Eskom to cover interest bills on Medupi and Kusile loans requires a 127 percent electricity price increase for ordinary consumers over four years. This has already raised power disconnection rates for poor households, and on Monday, Durban police made 25 arrests of shack-dwellers for electricity theft.

This multiple set of interlinked climate-energy-economic travesties can only be reversed by grassroots and labor activism. At the Durban COP 17, don’t expect a global deal that can save the planet, given prevailing adverse power relations. Instead of relying on paralyzed politicians and lazy bureaucrats, South Africa’s environmental, community, women’s, youth and labor voices will be demanding serious action to address the greatest crisis of our times:

- major investments in Green Jobs would let metalworkers weld millions of solar-powered geysers, for example, thus allowing Eskom to switch off power to BHP Billiton’s aluminum smelters and to halt new powerplant construction without net job loss;

- new public transport subsidies should reconfigure apartheid-era urban design and pull us willingly from single-occupant cars;

- an employment-rich zero-waste strategy would recycle nearly everything and compost our organic waste so as to eliminate methane emissions at the remaining landfills;

- more direct-action protests against major emissions point sources – Eskom, Sasol (apartheid’s wicked coal-to-oil company), the Engen refinery in South Durban and the new Durban-Joburg oil mega-pipeline, for instance – should better link micro-environmental struggles over local air, water and land quality to climate change;

- more ambitious Air Quality Act regulations would label – and then phase out – carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gas ‘pollutants’, as with the US Clean Air Act;

- government planning and utility board decisions would halt willy-nilly suburbanisation and ungreen ‘development’; and

- instead of North-South financing via destructive carbon markets, the demand for ‘climate debt’ would permit the flow of strings-free, non-corrupt and effective adaptation funds.

Through urgent adoption of genuine post-carbon strategies like these, by the time the COP17 rolls around, the world could see in Durban a state and society committed to reversing climate change.

But get real. Since none of these will be considered much less implemented by the current ruling crew, instead we’ll see a mass democratic movement rise, aiming to do to the climate threat what we did to apartheid and the deniers of AIDS medicines: defeat them at source, when respectively, old white politicians and their international business buddies, and Thabo Mbeki and Big Pharma, had to stand back and respect a new morality, a new bottom-up power.

***

- Music & Coal Mining

“Paradise”

1971: John Prine

Gigantic, 20-story tall strip-mining shovel that Peabody Coal Co. used to dig through more than 5,000 acres of Muhlenberg County, KY, 1963-1986, supplying TVA’s Paradise powerplant. Note full-size commercial bus at bottom of photo.In 1971, a song titled “Paradise” began to be heard on the radio. It was written and performed by country singer John Prine. The song, written for Prine’s father, is about how coal mining altered the countryside in western Kentucky. In this case, the type of mining at issue was strip mining. Companies such as Amax, Pittsburg & Midway, and Peabody Coal Company had either acquired coal land or engaged in strip mining in Muhlenberg County, Kentucky during the 1960s, and in some cases, for years thereafter.Peabody Coal Co., for one, was then supplying coal under contract to the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which had built a new coal-fired, electric-generating powerplant near the small town of Paradise, Kentucky.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, Peabody would supply huge amounts of coal to this plant – known then as the TVA Paradise Steam Plant. This particular powerplant — with three large generating units built between 1963 and 1970 — was located near huge coal deposits in Muhlenberg County that could supply the powerplant for many years.

Muhlenberg County in Western KY is mostly flat farmland, distinct from mountainous Eastern KY.As large-scale strip mining ensued there from the early 1960s through the 1970s, a substantial land area near Paradise, Kentucky – encompassing some thousands of acres – would be stripped.

In those days, especially during the 1960s and most of the 1970s, strip mine regulation and land reclamation, then governed by state laws, were minimal at best. As a consequence, land and water in the vicinity of Paradise suffered accordingly – as it did elsewhere in Kentucky and other states.

In the process, the small town of Paradise, a town dating to the 1800s, would become a victim as well, and would disappear entirely by the end of the 1960s. More on the town’s demise and the coal mining history in a moment.

John Prine’s song, “Paradise” — sampled below — is also known by some as “Take Me Back To Muhlenberg County,” or “Mr. Peabody’s Coal Train.” It was released in 1971 on his debut album, John Prine. In 2003, Rolling Stone rated the album at No. 458 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

John Prine was born in October 1946 and grew up in a Chicago suburb. His parents were natives and residents of Western Kentucky until the time when his father escaped the life of a coal miner and moved to Chicago.

However, as a child and a young boy, John spent many summers with relatives in the town of Paradise, where he took in the country environment, the culture, and lore of the region’s blue-collar struggles.

An earlier coal mine – a drift mine, one of the first commercial mines in Kentucky – had opened in the area in the 1820s. Paradise was also a river town, located on the Green River, where a ferry crossing operated. Prine’s song is about remembrance and loss; remembering happier times in that rural environment, and then seeing it altered by the “progress of man.”

Music Player

“Paradise” – John Prine

Audio Player01:2603:50

“Paradise”

John Prine

1971When I was a child my family would travel

Down to Western Kentucky

where my parents were born

And there’s a backwards old town that’s

often remembered

So many times that my memories are worn.Chorus:

And daddy won’t you take me back to

Muhlenberg County

Down by the Green River where

Paradise lay

Well, I’m sorry my son, but you’re

too late in asking

Mister Peabody’s coal train

has hauled it away.Well, sometimes we’d travel right down

the Green River

To the abandoned old prison down by

Airdrie Hill

Where the air smelled like snakes and

we’d shoot with our pistols

But empty pop bottles was all we would kill.(repeat chorus)

Then the coal company came with the

world’s largest shovel

And they tortured the timber and stripped

all the land

Well, they dug for their coal till the

land was forsaken

Then they wrote it all down as the

progress of man.(repeat chorus)

When I die let my ashes float down

the Green River

Let my soul roll on up to the

Rochester dam

I’ll be halfway to Heaven

with Paradise waitin’

Just five miles away from

wherever I am.(repeat chorus)

In October 2013, Lydia Hutchinson, writing a background piece on Prine at Performing Songwriter.com, brought together some of the history behind a few of his songs, including “Paradise.” Here’s what Prine had to say about the song:

…I wrote it for my father mainly so he would know I was a songwriter. Paradise was a real place in Kentucky, and while I was in the Army in Germany, my father sent me a newspaper article telling me how the coal company had bought the place out.

It was a real Disney-looking town. It sat on the river, had two general stores, and there was one black man in town, Bubby Short. He looked like Uncle Remus and hung out with my Granddaddy Ham, my mom’s dad, all day fishing for catfish. Then the bulldozers came in and wiped it all off the map.

When I recorded the song, I brought a tape of the record home to my dad; I had to borrow a reel-to-reel machine to play it for him. When the song came on, he went into the next room and sat in the dark while it was on. I asked him why, and he said he wanted to pretend it was on the jukebox…

Prine’s song did not crack the Top 40 on the pop charts in those days, but it did become something of an anthem for those trying to bring environmental law and order to the coal fields. At the time, surface coal mining was very weakly regulated – and in Kentucky even less.

A major push for increased coal development began in the 1960s, with coal then mined in more than 25 states, East and West. And after the Arab Oil embargo of the early 1970s, coal became a major alternative in the push for “energy independence.”

Throughout these years coalfield citizens and communities all across the country were pressing Congress for a federal strip mine law. Prine’s song became one of the popular expressions of that struggle, helping to bring the issue to a broader audience, and was also used to rally supporters.

Through the 1970s as well, Prine’s song was covered by a number of other prominent musicians – which also helped spread the song’s message.

Among those covering the song in 1972-1973, for example, were: Jackie DeShannon, John Denver, the Everly Brothers, the Country Gentlemen, and the Seldom Scene. The Everly Brothers also had family roots in Muhlenberg County.

But not everyone was excited by Prine’s song. Peabody Coal, for one, took issue with some of the song’s claims. During 1973, as the company battled strip mine activists, it offered a rebuttal to the song with a missive titled “Facts vs. Prine,” a broadside that noted, “we probably helped supply the energy to make that recording that falsely names us as ‘hauling away’ Paradise, Kentucky.”

“Mr. Peabody’s coal train” has a prominent role in John Prine’s 1971 song, “Paradise,” about coal mining’s damage.It’s true that the town of Paradise wasn’t literally hauled away by Peabody. But the town was bought out by TVA in 1967, with its remaining buildings bulldozed. And so, the town’s essence was wiped out; its geographic identity removed, and so too, in a sense, its culture and heritage. And although “Mr. Peabody’s coal trains” may not have been directly involved with the demise of Paradise, Prine’s song was essentially right on the bigger picture, as Peabody trains during the 1960s and 1970s hauled away lots of coal from numerous other places throughout rural America.

In Muhlenberg County near Paradise there were three companies involved with coal land during the 1960s and/or 1970s – Peabody, Amax, and Pittsburg & Midway – but Peabody appears to have been the major player. Peabody then was one of the top U.S. coal producers and among the largest coal companies in the world, and so a prominent name on the list of strip mine operators. Peabody was also the major player then supplying TVA’s Paradise coal plants.

Long lines of coal hopper cars loaded with coal on rail siding.In the late 1950s, TVA – the regional flood control and power authority created by President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s – began a major push in building coal-fired electric power plants. Near the town of Paradise, Kentucky, TVA acquired land for what would eventually become the Paradise Steam Plants – initially two units, both in the 740 megawatt range. TVA also began making long-term coal supply contracts with mining companies for thousands of acres of land in the immediate vicinity of Paradise. Some 6,000 acres of relatively flat land in the county held thick seams of coal not far beneath the surface. The beauty of this project for TVA was that the powerplants were built, essentially, right in the coalfield, dramatically cutting coal haulage and transportation costs. TVA officials by this time were also advocating “bigger, faster stripping shovels, more powerful bulldozers, improved explosives and bigger haulage trucks” to improve extraction efficiency. And with Peabody Coal, they had a willing partner on those counts. For Peabody, in Muhlenberg County, would proceed to use one of the largest pieces of mining equipment the world had ever seen.

1970s: Peabody Coal Co.’s “Big Hog” at work at the Sinclair Mine in Muhlenberg Co., KY, uncovering coal seams in a strip mine pit where an army of other smaller shovels and trucks load and haul the coal to TVA’s Paradise plant.

This colossal Peabody mining machine would be nicknamed “Big Hog,” and it was so big it had to be built on site, piece by piece. Bucyrus-Erie Company got the contract to manufacture the shovel. Then it had to be shipped by rail to the new mine near Drakesboro – named the Sinclair Strip Mine. New roads had to be built and a special rail spur was made, along with special rail cars, to haul in some of the parts. The huge shovel began arriving in pieces in 1962. Some 300 rail cars would bring in 5,000 parts and a 250-foot boom. The assembly took eleven months. Fully constructed, the Goliath-like machine stood 20 stories tall, weighed in at 20 million pounds, and cost some $7 million (in early 1960s money).Big Hog’s bucket could scoop up sizeable chunks of earth; each bite had a capacity of 115 cubic yards, more than a football field’s worth, or about 173 tons. The giant shovel was also a huge energy user, requiring a daily electric feed equivalent to the needs of a small town of 15,000 people. Big Hog went to work in 1963 at the Sinclair Strip Mine, and continued mining essentially non-stop supplying coal for the TVA Paradise plant. For the next twenty-five years, the Sinclair strip mines and the Paradise Steam Plant were partners in the production of electric power. During that time Big Hog would supply nearly 80 million tons of coal stripped from more than 5,000 acres of Muhlenberg County land. Thanks in part to Sinclair’s strip mine production, Muhlenberg County during the 1960s and 1970s was the state’s leader in coal production, and at times, the top U.S. coal producer as well.

A Peabody “loader,” a smaller shovel, loading coal from a Sinclair Mine pit into a 100-ton capacity coal haulage truck for the Paradise Power Plant, circa 1960s-1970s.Peabody’s Big Hog was assisted in its work by a variety of other machines, including sizable loaders and coal haulage trucks. The trucks could carry some 100 tons of coal to TVA’s Paradise Steam Plant. They would drive over the plant’s hopper bays, and usually while moving, dump their coal loads into the massive storage units. Then it was back to the strip mine pit for another load. All of the coal that was being mined at the Sinclair Strip Mine went to Paradise Steam Plant. At the time, it was the largest coal-fired power plant in existence. Plans were made for two more similar units to be built, but the decision was to build an even bigger generator. By the late 1970s, however, the toll on Muhlenberg County land began to come clear. One newspaper reporting out of Bowling Green, Kentucky in April 1978 ran the headline, “50,000 Acres Ruined by Strip Mining,” referring to the acres strip mined in the county, with a soil conservation agent saying another 50,000 acres were ruined. Some landowners in the county said they were hopeful that the new federal strip mine law could help reclaim the land.

April 1978 headlines from the “Daily News” of Bowling Green, Kentucky announcing the toll of “50,000 acres ruined” at the hand of surface coal mining in Muhlenberg County, Kentucky.By 1986, most of the coal had been played out at the Sinclair Strip Mine. The mine had been in operation some twenty-five years, sine 1963. Big Hog had been working full time for most of those years. The big shovel had been the center of attention at the Sinclair site for nearly three decades – the technological “star” that churned through the thousands of acres of Muhlenberg County land that laid above the coal seams there. But Big Hog had one more job yet to do. With some fanfare, and with the news media and some miners in attendance, as well as state and federal officials, including some from EPA, the giant Bucyrus-Erie 3850 shovel would now be used to dig its own grave.

In April 1986, the big machine would be buried in the last pit at the Sinclair Strip Mine. Peabody had sought state permission to bury Big Hog in the pit, and no objections were apparently made. Peabody agreed to remove all the toxic and hazardous fluids and materials from the shovel. Its tracks were removed and its boom laid flat. A dragline was used to bury Big Hog.

'Kentucky New Era' newspaper headline of April 7, 1986, on the burial of giant Peabody strip mine shovel.The Peabody Coal Co. would then become responsible for reclaiming the barren pits at the Sinclair Strip Mine under the requirements of the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977. Today, the Kentucky Fish and Wildlife division operates what is called the Peabody Wildlife Management Area at the former strip mine site.

Town of Paradise

The town of Paradise, meanwhile, wasn’t in the path of the giant Peabody shovel – although stripping near the town did occur by Pittsburg & Midway, according to some sources. Rather, the problem for Paradise came from the TVA’s coal-fired powerplants and the burning of the coal. In the early 1960s, after the plants first began operating, the town and power station co-existed. But soon, the fly-ash from the generating unit’s smokestacks became a big problem for residents. When residents would hang their wash out to dry, it would often turn gray with fly-ash. Other emissions were raising health concerns. And this was in the era before EPA. Over the years, in fact, the Paradise plant would become a problematic polluter, often cited by EPA for its emissions. But in Paradise during the 1960s, some residents, fed up with the pollution, began leaving of their own accord. TVA later installed electrostatic precipitators to control the fly ash. By then, many residents had left. TVA finally bought out the remaining residents and buildings, including the post office. All of the remaining buildings were later bulldozed.

An aerial view of the town of Paradise, Kentucky, circa 1965, before the final buy-out by TVA.Paradise had roots stretching back to the 1800s, first as a river trading post on the Green River called Stom’s Landing, then later, as a pick-and-shovel coal mining location, with a “drift mine” opening there in 1820, known as the “McLean drift bank.” A U.S. post office was established at Paradise on March 1, 1852. The town was located about 10 miles east-northeast of Greenville.

One rumor about how the town came to be known as Paradise – and there are at least three local stories on that count – has to do with an early pioneer family traveling up the Green River by boat, circa 1830s-1840s. During their trip, their young daughter became sick. The parents had stopped at several ports and towns along the river, but help was just not available. Without help, they continued on the river and were told by several old timers of a magical place further up river where Native Americans, centuries ago, had left an aura or an emanation that was believed to be able to cure people (Indian Knoll, an archaeological site near Paradise, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966). Several days later, the child was so near death that their last stop was to find a place to bury the child. Unbeknown to the parents, they had stopped at that magical place. The next day the child was better, and in a few days completely well. The parents believed, and would tell others, “this place must be paradise,” and decided to make their roots in the town, which later became known as Paradise.

An older map showing a portion of Muhlenberg County, Ky with the town of Paradise shown, now gone.In the 1960s, after TVA bought out the remaining residents of Paradise, the town ceased to exist. The last families moved out of Paradise in 1967, the same year that the post office closed and the Paradise Ferry ceased to operate. Soon after the TVA bought the town out, they tore down all the structures. At the powerplant, meanwhile, they built a third coal-fired boiler, “Paradise Unit 3”. Today, the Paradise Fossil Plant is the second largest plant in the TVA Fossil Fuels Plant Inventory and the largest power plant in the state of Kentucky. It has a rated output of 2,630 megawatts. It is composed of three units: units 1 and 2, twin 740 megawatt units, built between 1959 and 1962, and unit 3, a large cyclonic boiler rated at 1,150 megawatts, built in 1970. The plant also has three large natural-draft cooling towers. In 1985 a barge-unloading facility was added so that coal could be delivered by barge. That facility occupies a potion of land that was once part of Paradise. All that remains of the original town today is a small cemetery not far from the TVA Paradise plant (and some relatives of those interred there have complained to TVA about the cemetery’s condition).

TVA’s Paradise Power Plant, circa 1996, near the former site of the town of Paradise, Kentucky, which in this photo would have sat just beyond the left-hand end of the photo and field of view.Paradise, however, was not the only town in Muhlenberg County that made way for the “progress” of coal development. According to one account in a 1973 edition of Southern Exposure, journalist James Branscome and his wife Sharen reported on the demise of the town of Morehead, a town then located in Muhlenberg County. The residents of this town, apparently, were forced to sell their homes after the roads in their town were condemned for strip mining. Here’s the summary of what the Branscomes found, as reported in the September 1, 1973 edition of Southern Exposure:

…In researching the company’s record in the Division of Reclamation in Frankfort, the office that enforces Kentucky’s strip mining laws, we found that Peabody has succeeded in removing all the residents from the entire community of Morehead in Muhlenberg County. Since Kentucky law prohibits strip mining within 100 feet of a public road, coal companies must persuade the County Judge to declare the roads of no use to the county and send a copy of this declaration to the Division of Reclamation. (The roads of Morehead were thus condemned.)

Peabody, it was said, “had Judges in their pockets,” and could get rural roads condemned for coal strip mining practically for the asking.

We asked a Division of Reclamation official about Peabody’s success in the Morehead venture:

Q: How Many people live there?

A: Not more than 500, I think.

Q: Did they all sell to Peabody?

A: They had no choice. Everybody knows that they had no choice about selling. If they decide they want what you have, they’ll blast you out. Sure, they force people out.

Q: Does Peabody do this kind of thing often?

A: Peabody is the worst in this. They close roads every day. All they need is to get the Judge to write a letter and we have to let them strip. They’re forcing old people out of their homes all over the place. They just buy everyone around a person and then start pressuring him to sell. They always sell.

Q: Do the County Judges ever object to giving public roads to Peabody?

A: No, they have the Judges in their pockets. Several magistrates in Muhlenberg County work for Peabody. When they decide they want to strip a road, they’ll hire a magistrate who doesn’t work for them it it takes that to get the court’s permission.

Q: Does Peabody pay the county for the roads?

A: No, it looks like, at least, that the coal that is under a public road should belong to the public, but that isn’t the way it is.In addition to the Branscomes’ research, one report from the Woodson Baptist church, formerly of Morehead, noted: “In the Morehead Community the church grew and did prosper…. but then the sad day came when Peabody Coal Company bought all the property in and around Morehead and the church had to be moved to a new location.” In 1971, TVA also battled some Kentucky farmers in Union County, KY when it sought to build a giant 12.5 mile-long overland conveyor belt to move coal between two Peabody-run TVA mines and a river outlet. Twelve landowners went to court to stop the huge conveyor belt, which would be built on concrete supports. In the end, TVA prevailed and used its federal agency eminent domain power to build the conveyor system which would move 30,000 tons of coal each day. A similar fight around the same time occurred with four farmers in Ohio County, adjacent to Muhlenberg County, where Peabody invoked a private use of eminent domain under a little-used law allowing it to build a three-mile coal conveyor belt.

The Long View: Peabody strip mine operation supplying coal to the Paradise Fossil Plant, 1970s.

“Small Town Removal”

Strip Mine Depopulation

1960s-2010sThe loss of small towns like Paradise, Kentucky is not something that has occurred only in the “distant past” of the 1960s. Small towns have continued to disappear at the hand of coal development in the 1990s and 2000s. Coalfield citizens have been pointing out for decades that one of the major and often unheralded impacts of strip mining, especially in small rural communities, is the effect it has had – and continues to have – on driving people out of those communities. In some cases, the mining companies make no bones about it, as they set about directly buying up homes located near, or in the path of, planned or expanding mining operations. In other cases, the “driving out” is more subtle, and takes place over time, as in the daily harassment of mining activities, dust, truck traffic, blasting, the diminution of the local tax base, and families leaving one by one.Arch Coal Co., through a subsidiary, bought up more than half of the 231 houses in Blair, West Virginia in the l990s. In still other cases it’s the ruin of natural beauty; the despoliation of tourist and recreational assets that did have, or could have had, local economic value.

In the 1990s, as the Arch Coal Company was strip mining the mountaintop near Blair, West Virginia, it faced periodic complaints from residents who were being harassed by the constant dust and periodic rock fragments pelting their homes from strip mine blasting. Rather than fight constant complaints from homeowners, the coal company decided it would be easier to buy up the residential properties. So it set about doing just that. By August 1997, as Penny Loeb reported for U.S. News & World Report, Arch Coal, through a subsidiary, had bought up more than half of the 231 houses in Blair. Once the homes were vacated, they would often be stripped, and sometimes set ablaze by arsonists – the fate of at least two dozen such homes in the area.

2006: Mountain top strip mining proceeds in the mountains behind a home in Martin County, Kentucky.In southwest Virginia, the town of Roda once had a population of more than 500 residents. In July 2008, reporter Debra McCown of the Bristol Herald Courier, interviewed Pete Ramey who had made his home in Roda in 1948. Ramey said he had to leave town because of strip mining. “It was the dust, the noise, and the blasting and rocks flying from the blasting into homes,” Ramey told McCowan. “The fear is terrible, the fear of blasting on the mountains above you. It’s still going on.” Ramey explained that in the last decade the Roda community – like other coal communities in the region – had dwindled in population. At the time he spoke with McCowan in 2008, the town’s population had fallen to ewer than 100. “There’s people who still live there,” he said, “but they’re just gradually coming down the mountain as most of them are forced to move. The community’s been destroyed.” Residents in Roda and elsewhere are often confronted by strip mining that can come as close as 300 feet to their homes. And once the mining arrives, their choices are limited. With the blasting of nearby strip mines, they can’t sell their homes, unless the coal company buys them. Some never have that option. So they just try to bear the dust, blasting, coal trucks, and mining for as long as they can. But for others, it becomes impossible, and they decide to just walk away. It’s a scenario that’s been played out many times throughout Appalachia and other rural mining locations.

Stonega. Stonega is the name of another town in southwest Virginia beset by strip mining. Created in 1890 by the Virginia Coal and Iron Co., the town lies between two mountains – Bluff Spur and Ninemile Spur, and had taken form along the banks of Callahans Creek.“The fear is terrible, the fear of blasting on the mountains above you…”

– Pete Ramey, 2008 In the first two decades of the 20th century, Stonega had more than 2,400 residents — white and black, natives and immigrants from Hungary, Poland and Italy. The town was sometimes known by its sections: Red Row, Canal Row, Hunktown, Midway, and others. During its heyday, Stonega boasted a brass band, baseball teams and a gospel quartet. There was also a hotel, a commissary, a theater, a hospital, schools, four churches. The town, in fact, had been on the National Register of Historic Places since 2004. “[A] listing on the National Register,” noted reporter Tim Thornton of The Roanoke Times in August 2006, “ is no hedge against demolition, and whole sections are already gone.” Strip mining was moving ever closer to the town, and in 2006 Cumberland Resources, a mining company then operating a strip mine at the edge of Stonega, had set about buying out local residents. As for the remains of the town, Cumberland Resources sought to preserve the neighborhood’s history with photographs and a video it made before the buildings were demolished – the video supplying documentation for a safety record as well.

Lindytown, Boone County, WV.Lindytown. As far as small towns go, Lindytown, West Virginia was one of the smaller places in America. Yet, it was a place that had several generations of families, a town with a church and a school bus that picked up kids for school. A place from which men went off to fight for their country in foreign wars and returned to marry local women, raise children, and live their lives with friends and family. They enjoyed their natural surroundings, taking to the hills and woods, hunting the wildlife, searching for ginseng, or just wandering in the outdoors. Extended families often had adjacent or nearby homes in the area. One of the deep mines in the area – the Robin Hood No. 8 mine – had shut down, taking jobs with it. Some residents began leaving the area to find work. But then in the 2000s, Massey Energy began strip mining in the area. And not long thereafter, the company began acquiring the homes of local residents.

Massey’s general counsel, Shane Harvey, explained to the New York Times in April 2011 that many of Lindytown’s residents were either retired miners or their widows and descendants. They welcomed the opportunity to move to more metropolitan locations, he explained – places with easier access to medical and other services. Residents who sold homes to Massey also signed documents in which they agreed not to sue, testify against, or “make adverse comments” about coal- mining operations in the area. Local residents of Lindytown came to Massey, he said, expressing interest in selling. So Massey began making offers in December 2008. “It is important to note that none of these properties had to be bought,” Mr. Harvey said. “The entire mine plan could have been legally mined without the purchase of these homes. We agreed to purchase the properties as an additional precaution.” Elaborating later in writing, Harvey added that Massey voluntarily bought the properties “as an additional backup to the state and federal regulations” that protect people who live near mining operations. James Smith, 68, a retired coal miner from Lindytown, told the Times, that yes, some people did approach Massey about selling their homes. But he also explained that many residents decided to leave Lindytown only because the mountaintop operations above them in the hills had ruined the quality of life below. And when residents agreed to sell to Massey, many also signed documents in which they agreed not to sue, testify against, seek inspection of, or “make adverse comments” about coal-mining operations in the area.

In the spring of 2009, Lora Webb and her husband, Steve, a coal miner, packed up their possessions and left Lindytown, the place where Steve’s family had their ancestral roots. The Webbs had borne the strip mine assault – the giant, twenty- story dragline, daily explosions at the mine site, and the dust clouds and fly rock that rained down on their home and garden. They watched the nearby creeks and mountain hollows disappear and their community die. “It’s unreal,” Lora Webb remarked to a local newspaper reporter in the fall of 2008. “It’s like we’re living in a war zone.” So the Webbs moved on, as others did, leaving only a few families.

One who decided to stay was Quinnie Richmond, 85, who lives in a solitary home that displays five generations of family portraits in its small living room. Her son, Roger, a retired coal miner, lives next door. Quinnie, decided to sell various land rights to Massey, but wanted to remain in Lindytown. Roger’s uncle, Carson, who was killed in World War II, is buried in one of the small family cemeteries scattered in the mountains. “If he wanted to pay his respects,” The New York Times reported, “he would have to make an appointment with a coal company, be certified in work site safety, don a construction helmet and be escorted by a coal-company representative.” As regards family cemeteries in Appalachia, they are found quite extensively in small family plots throughout the region, and sometimes become entangled with strip mine sites as mining proceeds around their perimeters, leaving highwalls that make then inaccessible. AuroraLights.org has plotted some family cemetery locations on a map of the Coal River Mountain area of West Virginia (see Sources below).

As for the ever-vanishing Appalachian small town at the hand of strip mining, consider a comment made by Penney Loeb, who wrote the 1997 piece in U.S. News & World Report mentioned at the top of this sidebar, and also a 2007 book titled, Moving Mountains. Here she writes in 2003 about “disappearing towns” from her website:

…I am saddened when I return to communities I first visited five or six years ago and find the problems remain. Blair [West Virginia] got much coverage when the land company associated with the mine bought out more than half the residents, with many vacant homes quickly falling to an unknown arsonist. A similar scene was playing out in Mud River, but few people knew. A couple of years ago, I got an email from a woman whose family homeplace was one of the few remaining properties that Arch Coal had not purchased in Mud River. She had even written to ABC’s Primetime Live. Last summer, her family was featured on NOW with Bill Moyers. Still they are being forced to move away from a sweet little homestead that they loved.

Over the years, I watched as the communities [in West Virginia] disappeared along Rum Creek in Logan County. First Yolyn and Slagle went in the fall of 1997. Then Dehue at the other end of the creek in 2001. In between, a valley fill [from a strip mine operation] bulged nearly to the road in Chambers. Dust from the mining and preparation plant blanketed the communities…

…And apparently, the beat goes on. In 2014, the residents of a small community of about 219 residents and 100 homes in southern Illinois named Cottage Grove, were fighting Peabody Coal over the fate of their community, as the coal company wants to expand a strip mine site there by more than 1,000 acres, taking over a local road, and more. One local resident, citing the John Prine refrain, said “Mr. Peabody’s coal trains want to haul our community away.”

John Prine

Young John Prine, circa 1970s.As for John Prine, beyond his famous 1971 song “Paradise,” he went on to have a full and successful recording career. Prine had been a mailman in Illinois for a few years following high school, was drafted into the U.S. Army and was sent to Germany. When he returned home he resumed delivering the mail in Illinois. But during those years and while in the Army, Prine was playing his guitar and writing songs, mostly for himself. Then in 1970, after a few friends encouraged him to try some of his songs at an open-mike night at Chicago’s “The Fifth Peg” club, things began to change.

That fall, Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert, who had given up on a bad movie, happened to visit The Fifth Peg and heard Prine perform. Ebert was so impressed with Prine that he wrote an article for the Sun-Times beyond his normal film beat, titled, “Singing Mailman Who Delivers a Powerful Message in a Few Words.” It proved a glowing first review of Prine’s music and it helped to spread the word about Prine’s talents in Chicago and beyond.

Prine later met Steve Goodman, a singer-songwriter who had helped Arlo Guthrie with his hit, “City of New Orleans.” Goodman played one of Prine’s songs for Kris Kristofferson who was greatly impressed with what he heard.

Paul Anka, too, liked some of Prine’s Hank Williams-influenced songs, according to Rolling Stone. In fact Anka, along with Kristofferson, is said to have helped Prine land his first recording contract.

Jerry Wexler at Atlantic Records put out Prine’s first album – the John Prine titled 1971 album. That album also included “Sam Stone,” a song about a drug addicted Vietnam veteran that has the famous line: “there’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes.”

John Prine performing with guitar in later years.

Street scene from a portion of Paradise, KY, circa 1958.Prine’s music and songwriting have brought effusive praise from the likes of Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, and Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, among others. He has turned out more than 20 albums in his career, at least a dozen of which have appeared on the Billboard 200 albums chart. In addition to his first album, other fan favorites include Sweet Revenge (1973), Common Sense (1975), and Bruised Orange (1978). In 1984 Prine co-founded an independent record label, Oh Boy Records, which produced several subsequent albums, among them, Aimless Love (1984), German Afternoons (1986) and The Missing Years(1991).

In early 1998, Prine was diagnosed with squamous cell cancer on the right side of his neck, had surgery and radiation therapy, and after a time, returned to recording. That same year, George Strait had a No. 1 Country & Western hit with Prine’s “I Just Want to Dance With You,” bringing a writer’s windfall to Prine just as he needed funds for his medical care. Although the neck surgery had altered Prine’s voice, giving it a gravelly quality, he continued recording and touring. His album Fair & Square won the 2005 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album, and he also received the Artist of the Year award at the Americana Music Awards that September. Earlier in 2003, Prine had been inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. In November 2013, Prine was diagnosed with operable lung cancer ( unrelated to his earlier cancer), and had surgery to remove the cancer. By March 2014, he had resumed performing and touring.

As for Prine’s coal mining song, “Paradise,” he may have taken some artistic license in that song regarding the town and Peabody Coal, but on balance, his message about the social and environmental damages of strip mining – especially in the larger context of what had occurred and what was occurring in America’s coalfields during those years – was right on the money. In fact, “Paradise” still has resonance today, whether the struggle is about coal or any other form of social, environmental, or corporate bullying.

See also at this website: “Mountain Warrior: Harry Caudill, 1950s-1980s,” about a famous Kentucky author and strip-mine activist; “GE’s Hot Coal Ad,” about a General Electric TV ad touting coal use; “Sixteen Tons,” about a famous song from 1950s singer “Tennessee” Ernie Ford, which is also used in the GE coal ad; and, “Giant Shovel on I-70,” about strip mining in southeastern Ohio during the 1960s and `70s and the use of giant strip-mining shovels there. For other story choices please visit the Home Page or any of the category pages, such as the Politics page, each of which include thumbnail sketches and links to dozens of other stories. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

Please Support

this WebsiteThank You

____________________________________

Date Posted: 28 May 2014

Last Update: 15 June 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.comArticle Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Paradise, 1971: John Prine,”

PopHistoryDig.com, May 28, 2014.____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“John Prine,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, New York: Rolling Stone Press, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 784-785.

Lydia Hutchinson, “Behind the Songs of John Prine,” PerformingSongwriter.com, October 10, 2013.

Jim & Hilma Stewart Graphics, “Peabody Coal Company / Sinclair Strip Mine,” Rock PortKy.com, June 16, 2007.

“Paradise Kentucky,” TheStoms.com.

“Muhlenberg County, Kentucky,” Wikipedia .org.

“Paradise (John Prine song),” Wikipedia.org.

“John Prine (album),” Wikipedia.org.

“Paradise by John Prine,” YouTube.com, Posted July 20, 2007 by johngalt2626.

“Issues Page,” Citizens Coal Council Website.

J.C. Phillips, “The World’s Largest Stripping Shovel” (cover), Science and Mechanics, January 1963.

“Environment: The Price of Strip Mining,” Time, March 21, 1971.

James Branscome, “Paradise Lost,” Southern Exposure, The Institute for Southern Studies, September 1, 1973, pp. 29-41.

Frank Martin, “John Prine Goes Back to What’s Left of Paradise,” People, Vol. 2, No. 18, October 28, 1974.

Associated Press, “50,000 Acres Ruined By Strip Mining,” Daily News (Bowling Green, KY), April 5, 1978.

Associated Press, “Peabody Will Bury Strip-Mining Shovel,” Kentucky New Era, Monday, April 7, 1986, p. 5-A.

Associated Press, “River Queen Surface Mine Begins Closing [Peabody Coal / Muhlenberg County],” Kentucky New Era, June 12, 1991, p. 6-A.

Associated Press, “‘Paradise’ Returning to Mulenberg,” Kentucky New Era, September 1, 1992.

Penny Loeb, “Shear Madness,” U.S. News & World Report, August 11, 1997.

TVA Paradise Powerplant Photo, September 1997, KY Photo File, Fickr.com.

“Histories of the Local Churches,” Muhlenberg County Baptist Association (KY), Baptist History Homepage.

Tanya Anderson, “Finding Katie, A Graveyard in Paradise, Part 4,” Tanya Anderson Books.com.

“The Plight of the Paradise Cemeteries,” TheStoms.com.

“Paradise Fossil Plant,” TVA.com.

Penny Loeb, “Mining’s Impacts on Commu-nities,”WVCoalfield.com, March 2003.

Walter L. Creese, TVA’s Public Planning: The Vision, The Reality, University of Tennessee Press, August 2003, 304pp.

Tim Thornton, “Companies Strip Town of Homes in Order to Strip for More Coal; People Are Selling Their Properties and Leaving What Used to Be a Thriving Mining Area,” Roanoke Times (Roanoke,VA), Monday, August 7, 2006.

Tim Thornton, “Women Make Some Noise About Mining Blasts; Two Residents of a Coal Mining Town Are Fighting for an Ordinance That Would Limit Explosions,” Roanoke Times, Monday, August 7, 2006.

Shirley L. Stewart Burns, Bringing Down the Mountains: The Impact of Mountain-Top Removal on Southern West Virginia Communities, West Virginia University Press: Morgantown, 2007.

“Strip Mining Blasting Residents On Black Mountain,” The Appalachian Voices, Wednes-day, May 2, 2007.

Debra McCown, “Environmental Groups Sue To Halt Logging At Future Mine Site,” Bristol Herald Courier (Bristol VA), July 31, 2008.

“New ‘Coal Country Music’ CD Benefits The Alliance for Appalachia,” I Love Moun-tains.org, Friday, November 20th, 2009.

Debra McCown, “Coal Mining Practices That Destroy, Not Just the Land, But Entire Communities,” Bristol Herald Courier (Bristol, VA) February 8, 2010.

“Lindytown Twilight-ed Into Darkness,” Winds of Change, Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, (Huntington, WV), March 2010.

Dan Barry, “As the Mountaintops Fall, a Coal Town Vanishes,” New York Times, April 12, 2011.

Beth Wellington, “Mr. Peabody’s Coal Train Wants to Haul it Away,” The Writing Corner, June 22, 2012.

Alexis Bonogofsky, “Mr. Peabody’s Coal Train Has Hauled It Away…,” Wildlife Promise, June 27, 2012.

Todd Hatton, “John Prine and Paradise (KY) Lost”(radio clip, 7:18), WKMS.org, Murray, Kentucky, September 1, 2013.

Paul McRee, “Book Inspired by Western Kentucky Coal Mining,” SurfKy.com, October 25, 2013.

Theresa Dowell Blackinton, “How A Town Called Paradise Turned into Hell,” Moon Kentucky (Moon Handbooks Series), Avalon Travel, 2014, p. 399.

“Land Use Map – Coal River Mountain, W.Va.,” AuroraLights.org. Excellent Maps. See this Coal River Mountain area interactive map for a good introduction to the complexity of mining hazards in this one area of Appalachia.

Mud River (and other small towns hit by strip mining), WVcoalfield.com.

Tom Kane, “Classic Strip Mining Battle Looms,” Daily Register (Harrisburg, Illinois), January 8, 2014.

“Naperville City Officials In ‘Partnership to Destroy’ Downstate Town,” CityCouncil Watchdog.com, March 27, 2014.

“Blockade: Fighting Strip Mine Expansion Rocky Branch, Illinois,” The Understory, March 21, 2014.

“Top 10 Things You Didn’t Know About John Prine,” Alternative Reel.com.

“A Priceless First Peek at…John Prine,” in Tom Moon, 1,000 Recordings To Hear Before You Die, New York: Workman Publishing, 2008, pp. 614-615.

____________________________