Articles Menu

Democracy Now | DN | March 22, 2019

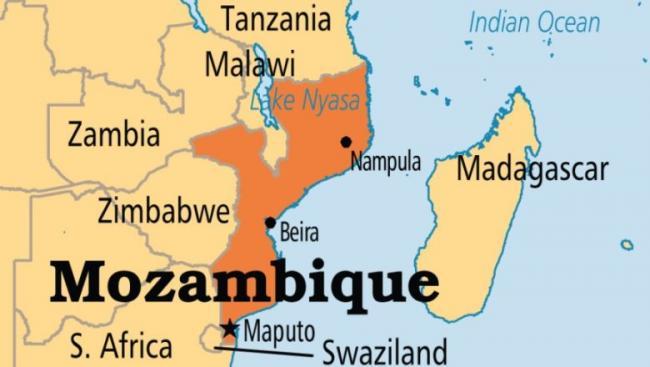

Cyclone Idai, the worst weather disaster in the history of the Southern Hemisphere, has caused extensive flooding and left tens of thousand homeless and more than 400 dead in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi. Officials say the death toll is over 400, and the number is expected to rise. More than 400,000 people could be displaced in Mozambique, and the country’s president says as many as 1,000 people may have been killed there alone. The storm dropped more than two feet of rain in parts of southeastern Africa—nearly a year’s worth of rain in just a few days—an extreme weather event that climate scientists say is consistent with models of climate change. We get an update from Dipti Bhatnagar, who is usually based in Maputo, Mozambique, where she is climate justice and energy coordinator at Friends of the Earth International. She joins us now from Penang, Malaysia.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, as we turn now to the worst weather disaster in the history of the Southern Hemisphere. Cyclone Idai has caused extensive flooding and left behind what looks like inland ocean since it made landfall last Thursday, battering Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi. The World Meteorological Organization has called the storm the Southern Hemisphere’s worst tropical cyclone on record. Officials say the death toll is over 400, the number is expected to rise. More than 400,000 people could be displaced in Mozambique, and President Filipe Nyusi said as many as 1,000 people may have been killed. The World Food Programme warned of a “major humanitarian emergency that is getting bigger by the hour.” This is WFPEmergencies Director Margot van der Velden.

MARGOT VAN DER VELDEN: We are confronted with severe flooding and cyclone effects; 600,000 people affected, possibly even going up to 1.7 and more million people affected by cyclone and flooding; communication completely broken; infrastructure severely damaged, particularly in the city of Beira, but also all the roads to Beira have been cut off.

AMY GOODMAN: Rescue workers in the flooded city of Beira struggled to reach survivors, who clung to trees or pleaded for help from rooftops, after 90 percent of the coastal city, which is home to half a million people, was destroyed. This is a survivor of the cyclone in Beira.

CYCLONE SURVIVOR: [translated] There is someone up there. There is a big tree over there. This person is sitting on that tree since Friday until today, without food or anything. How are they supposed to live? So I’m going there to help. There are other people needing help there—full of them, actually. I already rescued my family, always using this canoe.

AMY GOODMAN: Cyclone Idai dropped more than two feet of rain in parts of southeastern Africa—nearly a year’s worth of rain in just a few days—an extreme weather event that climate scientists say is consistent with models of climate change.

For more, we are joined by Dipti Bhatnagar by Democracy Now! video stream. She’s usually based in Maputo, Mozambique, where she’s climate justice and energy coordinator at Friends of the Earth International, but is joining us from Penang, Malaysia.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Dipti. Can you explain the extent of the damage?

DIPTI BHATNAGAR: Thanks, Amy. It’s really heartbreaking to be away from home at a time like this. But interestingly enough, we have been at a climate justice meeting here in Penang, Malaysia. And back home, our communities, our people are getting battered from all sides by this disaster.

So, of course, as you said right now, the cyclone, Idai, has hit the coast, and then it’s gone inland into Zimbabwe and Malawi, and affecting hundreds of thousands of people and wiping out 90 percent of the city of Beira. I live in the south, in the capital, in Maputo, and that area has not been hit. But we are in touch with people in Beira—family, friends, family of colleagues—who have been hit. And we are still waiting for information from a lot of people that we haven’t heard from. And, of course, this is a huge disaster to have hit Mozambique.

And already, about two weeks ago, when I was home, we heard of a lot of flooding happening in this Tete province, which is the Zambezi River Basin. So, basically, there are two river basins that have been affected by flooding, and people sort of trapped in between. And some of it is related to the cyclone, and some of it is related to rain upstream and the catchment and the dams in Zimbabwe letting go of water. And that’s also affected a lot of people.

And as you just heard, it’s absolutely heartbreaking. I mean, you’ve had people stuck on rooftops. You’ve had people stuck without water and food. And a lot of organizations from Mozambique, including mine, which is Justice Ambiental, meaning “environmental justice,” from the capital, which is Friends of the Earth Mozambique, has been trying to do whatever we can to support the relief efforts, because the very most urgent thing that’s needed right now is to be able to get emergency relief to people who are—still could have a chance to survive.

AMY GOODMAN: Hundreds of thousands have been displaced over the past week because of Cyclone Idai. Residents of affected areas are describing the devastation.

DISPLACED SURVIVOR 1: [translated] I thought we would all be dead. My home collapsed.

DISPLACED SURVIVOR 2: [translated] I was with my children inside our home talking, because it was raining. And then we heard the mountain exploding, and then the water started flowing through the streets and arrived at our house. And we had to run away.

DISPLACED SURVIVOR 3: [translated] Here, we don’t have anything to eat here. No food, nothing. It’s a problem. At night, we don’t eat. We don’t even have a blanket to cover ourselves with. We only have the clothes we are wearing. It’s hard to die. We want to live, but we suffer. We have been suffering until today.

AMY GOODMAN: Dipti Bhatnagar, can you talk about the link between climate change and this cyclone?

DIPTI BHATNAGAR: Absolutely, Amy. I think—so, I mean, there always have been cyclones in the Indian Ocean, but the intensity of it is getting much stronger, and the breadth of it is getting a lot stronger. So, I’m wearing a T-shirt which shows you the map of Mozambique. And, of course, you see Madagascar, which actually protects Mozambique from these types of events in the Indian Ocean. But as the intensity has increased due to warming oceans and due to the climate crisis, this type of extreme weather event is impacting and hitting with so much more intensity. So, we—you know, in Mozambique, we’ve always known that we are going to be really impacted by climate change. We are a downstream country. We are a very, very flat country. And we have faced floods before. And we knew that this is going to be our fate, that as the oceans warm and as the atmosphere warms, this is going to have direct impacts on our people. And that’s what you see happening right now.

AMY GOODMAN: Kenyan author Shailja Patel called out ExxonMobil over its involvement in Mozambique amidst the climate disaster, writing. “'ExxonMobil, which is developing giant gas deposits off northern Mozambique, said it would donate $300,000 to relief efforts.' @exxonmobil’s 2018 quarterly profits: $6 BILLION $300,000 is less than 7 minutes of their 2018 profits.” Author and activist Naomi Klein retweeted Patel’s tweet, adding, “Tell Exxon to [pay] its climate debts, starting right now!” Dipti Bhatnagar, your response?

DIPTI BHATNAGAR: I absolutely agree with that analysis, from Shailja and from Naomi. I mean, Mozambique did not create this climate crisis. Our people have contributed almost nothing to the climate crisis. But this is the irony of the climate crisis, that it affects those who did not do anything to create it, and it affects those the most. So the poorest and the most vulnerable people on the planet are going to be affected the most. And that’s what’s happening in Mozambique right now.

And we really want to call out those who are responsible. So this is about the rich countries, Amy, where you are are sitting at the moment, the United States. This is about Europe and Australia and Japan. And for years, your societies have built up your societies using the fossil fuels, and now we know this is what it’s caused in the atmosphere. So we call out the rich countries. Even the U.K. government has promised some amount of money, but the U.K. government, just a few days ago, has approved a new coal mine in their territory. So, this is an absolute affront, you know? We need to deal with the climate crisis. We need to stop dirty energy, dirty and harmful energies everywhere. But this is about historical responsibility. So, that needs to happen in the Northern countries first, to stop fossil fuels, to stop dirty and harmful energies.

And then, as you said, we don’t want this in our countries, either. So, our organization, JA, Justice Ambiental, is fighting against the exploitation of gas in the very north of Mozambique, right under Tanzania. And it’s ExxonMobil that’s involved. It’s Eni from Italy that’s involved. And it’s Anadarko, which is another U.S. corporation. And we have been working with a group of allies from all over the world, because there is a huge rush for this gas field in Mozambique. And we are going to fight, because we don’t want dirty energy in our countries, either. I mean, 70 percent of the people of Mozambique don’t have access to electricity, and obviously the situation is going to get much worse after this disaster because of how many power lines have been knocked off and because of how many villages have disappeared. But this is not the way to get energy. We don’t have any more space to keep emitting these greenhouse gas emissions and to have this horrible dirty energy, which is affecting people on the ground.

We’re pushing for repayment of the climate debt, which means we didn’t create the crisis, so those who did give us the finance to be able to actually deal with this on the ground. And, you know, we want to fight for people-centered renewable energy for our people. That’s the future that we want to see. And, of course, this disaster has showed us that we need to be able to build up the resilience of our people. We need to have survival strategies for people, because the ocean is coming into people’s houses. I mean, agriculture is going to start failing. We’re seeing impacts intensifying all over the world. And how are the poorest and the most vulnerable people, who don’t have these strategies of survival—how are they actually going to live? So this is what we are fighting for: repayment of the climate debt, stop the dirty and harmful energies, and let’s [inaudible]. Let’s have an energy transformation towards people-centered renewable energy. That’s what we’re fighting for.

AMY GOODMAN: Dipti Bhatnagar, I was wondering if you can end by talking about the significance of the climate school strike, led by Greta Thunberg in Sweden, who’s just been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize, the 16-year-old climate activist—millions of young people walked out of schools across the world—and also what’s happening in the United States with this new Congress, the most diverse Congress in U.S. history, with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the New York congressmember, pushing for the Green New Deal, what this looks like from your vantage point in Mozambique, and right now in Malaysia, where you’re at a climate summit—the same country that’s historically the biggest greenhouse gas emitter and where President Trump has pulled the United States out of the U.N. climate summit and the Paris peace accord—well, not the summit: They go to push fossil fuels—but the Paris climate accord.

DIPTI BHATNAGAR: Absolutely. That’s a wonderful question. Actually, we’ve been meeting with some of the Malaysian activists who organized the strike in the city of Penang last week, on Friday. And I think it’s wonderful, what’s happening across the world, you know, initiated from Greta Thunberg in Sweden, who our team from Friends of the Earth were with her, and allies were with her, in the Poland U.N. climate negotiations last December. I think it’s absolutely wonderful. And what she’s saying about system change is very, very critical, because that is what it’s going to take. That level of transformation is what we need to be able to stop the climate crisis, but also to serve the people who the current system never served, those who don’t have electricity and those who struggle to have food on the table. I mean, we’re talking about a world of increasing inequality. So, we, as Friends of the Earth Mozambique, as Friends of the Earth International, we are really pushing for this transformational agenda. And I was really happy to see Greta actually talking about it.

However, I don’t think that the school strikers in some of the other countries are actually making those links. And that’s where I think we want to offer a connection. Those of us from the South, from the Southern countries, we would love to talk to you. We would love to talk to the school strikers. We would love to talk to those in the parliament in the U.S. who are pushing this Green New Deal, to say, “This is absolutely wonderful, what you’re doing. Let’s not forget about equity. Let’s not forget about the South. Let’s not forget about historical responsibility.” So, I think the work that’s happening is wonderful. I think we want to make sure that they realize we are also in the boat with them, us in the South, and that there is a responsibility that they have, not just to stopping climate change, but actually doing it in an equitable way. So, I’m offering myself. I am available anytime to speak to school strikers, to speak with people in the U.S. Congress who are allies. We’ve just been talking about this at our climate justice meetings. We really want to reach out. We really need to strengthen the narrative of equity and of historical responsibility. Within the climate strikes, within the Green New Deal, I think there are wonderful opportunities, but I think we need to remember the South.

AMY GOODMAN: Dipti, I want to thank—I want to thank you very much, as you talk about remembering the South, Dipti Bhatnagar with Friends of the Earth International, climate justice and energy coordinator, usually based in Maputo, Mozambique, but joining us now from a climate justice conference in Penang, Malaysia.