Articles Menu

The saga surrounding the Trans Mountain pipeline and tanker expansion project (TMX) saw two major developments this month.

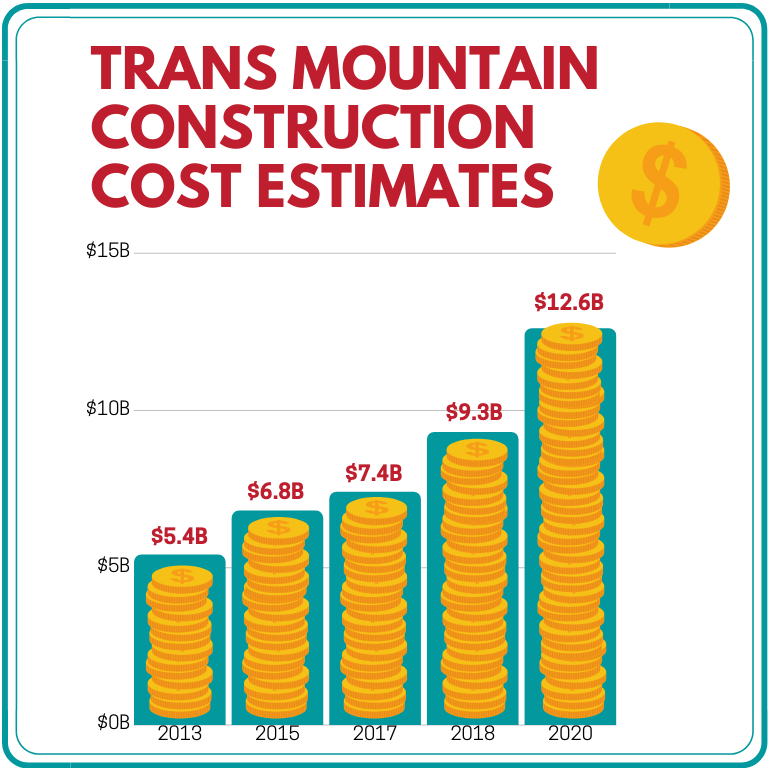

First, the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed a legal challenge by four Indigenous parties to the federal government’s re-approval of the project. And then a few days later, the Trans Mountain Corporation released an updated construction cost, increasing the estimated price tag by 70% to $12.6 billion. Combined with an additional $600 million contingency fund, the total cost to build TMX has jumped to $13.2 billion.

Both of these developments set the stage for the next chapter in the TMX story. Here, we discuss what they mean for the future of the project.

The Federal Court of Appeal Decision

On February 4, 2020, the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) released its much-anticipated decision (the Coldwater case) on the appeals of the second approval of TMX. The court found that the federal government’s second round of consultation with affected First Nations was “adequate,” in a judgment that focused on the “reasonableness of the Governor in Council (Cabinet) decision, including the outcomes reached and the justification for it.” [para 29]

Two factors significantly affected the outcome of the Coldwater case.

First, the FCA’s leave decision of September 4, 2019 limited the Coldwater case so it only considered Indigenous consultation between August 30, 2018 and June 18, 2019 – the period between the previous court decision that quashed the pipeline’s approval (the Tsleil-Waututh decision) and the second approval by federal Cabinet. The leave decision excluded legal arguments on conflict of interest and bias, as well as statutory issues such as compliance with the National Energy Board Act, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act 2012, and the Species at Risk Act, among others. The leave decision also excluded applicants who were not First Nations involved in the 2018 Tsleil-Waututh case.

It is worth noting that several parties have sought leave to appeal the September 2019 decision limiting the scope of the Coldwater case, and we are still waiting to find out if the Supreme Court of Canada will hear the appeal.

The second factor was the FCA’s application of new case law from the Supreme Court of Canada – known as the Vavilov trilogy. Vavilov was a highly anticipated SCC case (among administrative law nerds at least) that was meant to clarify the standard of review that Canadian courts should use when administrative law decisions are appealed. The Vavilov decision was released after the FCA had concluded the oral hearing in Coldwater, and parties were invited to make additional submissions on the impact of Vavilov to the Coldwater case.

In the end, the FCA relied on Vavilov to inform its analysis of the adequacy of consultation in Coldwater, and in doing so, may have changed the nature of consultation cases moving forward.

Specifically, in Coldwater the court departed from its past practice of reviewing the evidentiary record to determine the adequacy of consultation, following Vavilov:

[28] In conducting this review, it is critical that we refrain from forming our own view about the adequacy of consultation as a basis for upholding or overturning the Governor in Council’s decision. In many ways, that is what the applicants invite us to do. But this would amount to what has now been recognized as disguised correctness review, an impermissible approach (Vavilov, para. 83)

In its decision, the FCA panel was critical of the arguments made by First Nations during the hearing, even though Vavilov had not yet been decided. Effectively, Vavilov moved the goal posts for consultation cases, but only after the expedited Coldwater hearing was finished.

Instead of looking at what happened during consultation to determine whether it was meaningful and upheld the honour of the Crown (the test for meaningful consultation), the FCA deferred to Cabinet’s own assessment of whether it had fulfilled its duty to consult and accommodate. The court held that Cabinet’s decision, including the outcome reached and justification for it, was reasonable, relying on Cabinet’s own decision document and accompanying explanatory note.

As one commenter noted:

How likely is it that a government would judge it had failed to comply with its constitutional responsibilities towards First Nations and therefore refuse to approve the pipeline? Is its self-judgment objective and disinterested? The cabinet’s interpretation of a constitutional duty should be more than just reasonable; it should be correct. For the FCA to review the correctness of the cabinet’s decision, far from being “impermissible,” may well be required.

Reconciliation

The FCA discusses the concept of reconciliation as a guiding principle of consultation at length in Coldwater – the buzzword appears 24 times in the decision. The views of the court on reconciliation are summarized in paragraph 53 where it states “reconciliation does not dictate any particular substantive outcomes” and “the law does not require that the interests of Indigenous peoples prevail.” It is this language that caused Indigenous lawyer Naomi Sayers to opine that this case means that Canada has a veto over Indigenous peoples.

There are many other problematic elements of the Coldwater decision – too many to cover in this blog post. Instead, I will focus on two of them here.

First, the court conflated the arguments regarding bias and conflict of interest, which were excluded from this case by the September leave decision, with arguments made by First Nations that Canada entered into consultation with a closed mind (with the ultimate decision to approve the project already made). By conflating these two distinct concepts, the court was able to dodge important questions about whether the federal government, also the owner and proponent of this project, could engage in consultation with an open mind and in good faith. This line of thinking also allowed the court to rely exclusively on Cabinet’s assessment that its own consultation on its own pipeline was adequate, as discussed above.

Second, at paragraph 78 the court states that 120 of 129 Indigenous groups that were consulted on the project either “support it or do not oppose it.” This number was repeated over and over by pipeline supporters following the decision.

The trouble with this statement is that it is simply not true. While the exact number of Indigenous groups who support or oppose the project is difficult to determine with precision, this statement infers that the only way to express opposition is to challenge a project in court. The reality for most First Nations is that litigation is not always possible, due to the enormous financial and human resource costs – often running into the hundreds of thousands of dollars for a legal proceeding of this nature.

Further, it ignores that not all nations’ rights will be equally impacted by the project. Two of the litigants, for example, Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish face risks associated with marine oil spills from the planned seven-fold increase in heavy oil tanker traffic that are different in magnitude and nature from those facing others, while Coldwater’s sole drinking water source is at risk, and the Ts’elxwéyeqw nations have established fishing rights that will be affected.

Indeed, we know that Trans Mountain spent years trying to meet with every single Indigenous community to get them to sign Impact Benefit Agreements. While about a third of these (43 nations) signed Impact Benefit Agreements, it could reasonably be concluded that the remaining 86 nations do not support the project.

Either way, these numbers provide a false context to the issue because they undermine the very purpose of rights, be they Aboriginal rights or other human rights. Rights are meant to be a shield against the tyranny of the majority. A linear project like a pipeline will necessarily cross many traditional territories and homelands, and therefore should uphold the rights of all First Nations whose rights are impacted.

Skyrocketing costs

Three days after the FCA released its decision in Coldwater, Trans Mountain Corporation (the crown corporation that now owns the original pipeline and expansion project) released its updated cost estimate for the project.

According to Trans Mountain, the new cost estimate is now $12.6 billion, with an additional $600 million in contingency, bringing the total cost to $13.2 billion. This represents an increase of more than 70% from the $7.4 billion estimate used by Canada when the government purchased the project, after Kinder Morgan decided to abandon it. The original cost estimate when the project was proposed in 2013 was $5.4 billion.

The $13.2 billion is in addition to the $4.6 billion spent by Canada to buy the existing Trans Mountain pipeline from Kinder Morgan in 2018, meaning the total cost to Canadians is at least $17.8 billion.

The estimate was a shock to some, but independent economist and former ICBC President Robyn Allan, had already estimated a cost of $12 billion in her December 2019 analysis (PDF). In that same report, Allan calculates that a $12 billion price tag would result in up to $8 billion in subsidies by the Canadian public. Considering how much the government overpaid for the original Trans Mountain system, the resulting tolls which don’t cover the cost of acquisition and construction, and $1 billion required for oil spill cleanup costs as part of the Oceans Protection Plan, Allan suggests that taxpayers will be left with a multi-billion dollar bill to pay for the project.

Just last year, the Parliamentary Budget Office released its analysis of the TMX project, based on publicly available information at the time. The PBO found that Canada overpaid for the project, and that a one year delay or 10 per cent increase in cost could render the project uneconomic. With the recent update from Trans Mountain far exceeding both of those figures, it is now more likely than ever that if TMX gets built, it will become a stranded asset before it is ever paid off – with the Canadian public holding the bag.

Why didn’t the court consider escalating costs and reduced economic need for the project?

You may be wondering why the Federal Court of Appeal – or Cabinet or the NEB before it – did not consider the significantly reduced economic justification for the project, based on updated cost estimates. Unfortunately, while many First Nations and intervenors called on the court to do so, this issue was also excluded by the September 4, 2019 FCA leave decision, and therefore was not a factor in the determination in Coldwater.

What does this all mean? It means that while Trans Mountain has passed one legal hurdle (subject to appeal), the infringement of Aboriginal rights may be permitted for a project that does not deliver the economic benefits that it promised. Kinder Morgan knew that when the company decided to abandon the project in 2018.

Trans Mountain Corporation stated in its cost update that about $2 billion of the $13.2 billion construction cost had already been spent. That leaves over $11 billion still to spend to complete construction, assuming no further delays (unlikely).

Rather than waiting to see if TMX pays itself off or generates profit to fund renewable energy as federal politicians are stating, why not spend that $11 billion directly on renewables today, employing out-of-work oil workers? Canada still has time to walk away, and stop spending public money on what can only be described as a white elephant.

Top photo: 'Raise a Paddle' water ceremony near TMX Westridge terminal, 2017 (E.Kung)