Articles Menu

Feb. 14, 2024

Anyone reading about proposed amendments to B.C.’s Land Act might believe there are major changes afoot.

Private property is at risk. Outdoor recreation is threatened. Water access, mining, forestry and agriculture all now hang in the balance as the BC NDP threatens to quietly take away every land-use right that British Columbians currently enjoy.

It’s a move meant to “cripple” society, according to commentary in the National Post by conspiracy-prone commentator Bruce Pardy later republished by conservative think tanks the Fraser Institute and the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

B.C. Premier David Eby is “preparing to bring his province to its knees.”

The government, the analysis goes, is about to quietly pass control over the vast majority of its land base to the First Nations who stewarded it for millennia.

Except it isn’t.

The furor erupted last month following a blog post by law firm McMillan LLP. B.C., the lawyers wrote, was laying the groundwork for agreements that would give Indigenous groups “veto power” over decisions about Crown land, which covers 94 per cent of the province.

As commentary became increasingly frenzied, pundits and politicians talked over First Nations leaders who called the claims “inaccurate and unhelpful.”

BC United Leader Kevin Falcon wrote in a Feb. 5 statement that the proposed changes were secretive, misleading and undemocratic. They would give “veto power” over most of B.C.’s land to “five per cent of the population.”

Conservative Party of BC Leader John Rustad went a step further, suggesting B.C. repeal the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which passed unanimously in 2019. Rustad voted in favour of the legislation.

Rustad, like Falcon, also argued that the changes could mean “returning all traditional lands.”

Except the changes wouldn’t do that — they are less radical, and more creeping bureaucracy.

What is the Land Act?

Mainland B.C. became a colony in 1858 and, shortly after, passed a series of proclamations asserting control over the land and its resources. The 1859 Land Proclamation granted the Crown authority over “all the lands in British Columbia, and all the mines and minerals.” It referred to those lands as “unoccupied.”

These proclamations laid the groundwork for what is today’s Land Act — the primary legislation used to manage the land base and issue land tenures such as leases, licences, permits and rights-of-way.

B.C. has historically based both its economy — mining, forestry and agriculture, to name a few examples — and its identity on this large land base.

Why the changes are coming

But B.C. was, of course, occupied prior to becoming a province. In recent decades, court cases like Calder, Haida and Tsilhqot’in have affirmed First Nations’ rights on their traditional territories and the government’s need to consult.

When B.C. passed DRIPA several years ago, it was a step toward incorporating those rights into law and avoiding lengthy and costly legal battles. The province has described DRIPA as a framework to move forward on reconciliation. It’s meant to eventually bring all laws in the province in line with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

DRIPA’s implementation is meant to be incremental and the proposed Land Act changes are the anticipated next step. They would “allow the government to enter into agreements with First Nations on what is likely very specific, large-scale projects,” Lands Minister Nathan Cullen told The Tyee. “A lot of the fear-mongering and disinformation has attempted to say everything across 95 million hectares of public lands is changing tomorrow, which is not the case.”

What the changes also wouldn’t do is affect the province’s 40,000 existing land tenures or the 2,500 renewals it issues on an annual basis, Cullen added.

What the changes would do

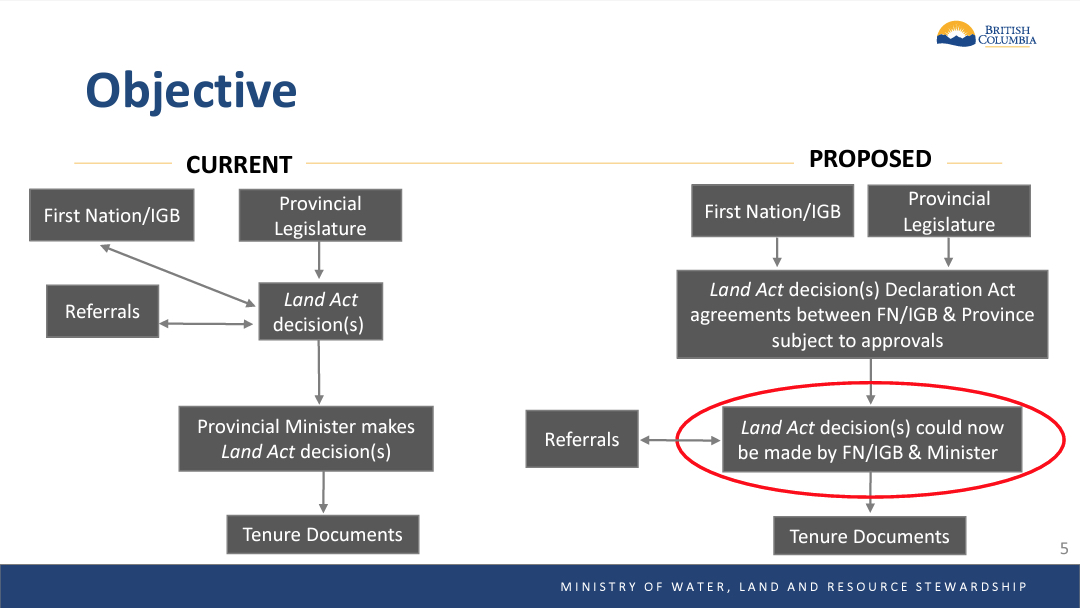

DRIPA introduced wording that gives B.C. authority to “negotiate and enter into an agreement with an Indigenous governing body.” The wording in sections 6 and 7 opens the door to joint decision-making agreements with First Nations. But in order to do that, existing legislation needs to be brought in line with DRIPA by adding similar wording to each act.

While the changes have been described as “radical,” they are basically procedural. Any future agreements on decision-making facilitated by adding wording from DRIPA’s Section 7 to existing legislation would be subject to public consultation and cabinet approval.

If anything, the changes are creating more red tape for First Nations, said Jessica Clogg, executive director and senior counsel with West Coast Environmental Law.

“In my view, B.C. has been incredibly conservative, narrow and bureaucratic in its approach to DRIPA sections 6 and 7.” Rather than pave the way for First Nations decision-making, the changes could actually present more roadblocks, Clogg said.

“That’s what has gotten a bit lost in the inflammatory rhetoric,” she said. “If anything, my worry is that it will be too incremental.”

Others agree that the proposed changes would not grant sweeping authority to First Nations.

Writing in the Times Colonist, lawyer Roshan Danesh called the process for entering into any future decision-making agreements with First Nations “public, transparent and frankly a bit onerous.”

“The day these Land Act amendments are passed in the legislature, nothing will change about land tenuring in the province,” Danesh wrote. “What they will do is create space so that if an agreement is ever completed under Section 7, that agreement can be implemented.”

Is the Land Act the first legislation to change due to DRIPA?

In a word, no.

In recent years, B.C. has made similar changes to forest, child welfare and emergency management legislation, all of which now accommodate Section 7 agreements.

When B.C. passed its new Environmental Assessment Act in 2018, it pre-emptively built joint decision-making with First Nations into the legislation in anticipation of DRIPA.

The province has already signed its first two Section 7 agreements with the Tahltan Nation, both relating to the expansion of mines on the nation’s traditional territory. As he signed the second agreement in November, B.C. Environment Minister George Heyman described the work ahead as collaborative.

Rhetoric calling the Land Act changes “unprecedented” appears to reference industry’s calls for regulatory certainty. While alarmists have said the changes will make things less predictable for business in B.C., there’s ample evidence that the opposite is true.

The Supreme Court of Canada has repeatedly upheld the duty to consult with First Nations. The more clearly governments set out a legal process to do that, the more certainty there will be — as well as fewer costly court cases and unexpected interruptions for industry.

“Working together, coming to common agreements, increases predictability. Period,” Cullen said. “Rather than going through more court cases, going through more conflict, why not enable the possibility of coming to a shared understanding over proposed projects, to give that predictability and to know early on if something is just not viable?”

Last week, BC Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief Terry Teegee wrote in the Vancouver Sun that “the path to consent-based decision-making signifies an essential step toward greater certainty, shared prosperity, and a more just relationship between constitutional partners.”

Even Geoff Plant, former B.C. attorney general under the BC Liberals, weighed in, saying the Land Act amendments could replace the current atmosphere of uncertainty with “fair, principled, transparent and accountable shared decision-making agreements.”

How is ‘consent-based decision-making’ different from a veto?

So, is it a “veto”? The word has become politically charged, suggesting that First Nations aren’t capable of making fair assessments about land-use decisions.

“The word ‘veto’ has taken on this connotation of a racist assumption that nations wouldn’t be reasoned and adhere to their own legal orders and make informed decisions as governments,” Clogg said. “For example, we don’t say, when B.C. fails to issue an environmental assessment certificate, that they ‘vetoed’ that project.”

In its recent statement, the B.C. First Nations Leadership Council also expressed concern, saying many reactions to the proposed Land Act amendments “rely on outdated, mistaken, and regressive views” on First Nations rights.

“Contrary to comments that have been made about the proposed Land Act amendments, they will not grant a ‘veto’ to First Nations governments, and they will not immediately alter the existing land tenure system in British Columbia,” the statement added.

When The Tyee asked about the leadership council’s statement, a spokesperson for BC United doubled down on the party’s statement that the proposed changes would give veto power to a small percentage of the population over the vast majority of the land base.

“We would encourage everyone interested in this issue to look at the government’s slide deck,” the spokesperson wrote, adding that changes would affect “everything from grazing leases and rights-of-way, to all land tenure-based decisions on public lands.”

Cullen countered that BC United recently set out a very similar policy to the proposed Land Act changes at the BC Natural Resources Forum. The policy was titled “Enable Indigenous participation and ownership in B.C.’s natural resource projects.”

BC United disagreed. “The policy we set out is designed to foster direct economic partnerships and enable Indigenous participation and ownership in B.C.’s natural resource projects,” their spokesperson wrote.

Why am I just hearing about this now?

There is one thing everyone does agree on — that the BC NDP could have done a better job of introducing the changes. Cullen acknowledged the government’s failure to adequately inform the public, saying, “We’re now correcting and resetting the consultation process.”

While there are many ways the province could have launched its consultation process (it didn’t, for example, issue a news release), it is standard practice that the wording of any proposed changes are kept confidential during the drafting process and are made public only once they are tabled in the legislature, Clogg said.

The province is currently accepting written submissions from the public. Asked if he would consider extending the March 31 deadline to provide comment, Cullen was noncommittal.

The current plan is to introduce the new legislation during the spring legislative session — which begins April 22 — and finalize it prior to the fall election. The province hopes to begin negotiating agreements with Indigenous governments by late spring.

What’s the impact on First Nations and reconciliation?

Ultimately, it is Indigenous communities who are caught in the crosshairs of a debate that’s become rife with fear-mongering and racist undertones.

In a video posted to social media last week, BC Green MLA Adam Olsen, who is a member of the Tsartlip First Nation, called on politicians to “stop using First Nations people as a political football.”

“I’ll start by asking Kevin Falcon and John Rustad directly to stop dragging First Nations into their political fight,” said Olsen.

“It guts me that the BC NDP created the space for you and that you are all too happy just making stuff up,” he said. “As difficult as it is for many to understand, the BC United so-called economic reconciliation and the B.C. Conservatives’ promise to scrap the Declaration Act are aggressive approaches that deny First Nations rights and title.”

As for whether the dispute could actually result in DRIPA being repealed, Clogg doesn’t believe that it could, because the underlying Indigenous rights that led to its being passed would remain, leaving governments, industry and First Nations to hash out their differences in court.

“Those rights are here to stay,” she said. “Do I think there will be a lot of political fear-mongering? Yes, I think that’s what we’re seeing. It makes me very sad.

“Ultimately, I believe that Canadians are better than that.”

The public has until March 31 to provide input about proposed Land Act amendments through the province’s website

Amanda Follett Hosgood is The Tyee’s northern B.C. reporter. She lives in Wet’suwet’en territory.

[Top photo: After years of conflict over resource development in an area known as the Sacred Headwaters, the Tahltan Central Government became the first nation to sign Section 7 decision-making agreements with the BC government. Photo by Amanda Follett Hosgood.]