Articles Menu

Critics of public sector inefficiencies have long declared that “government should be run like a business.”

A business such as, say, Pacific Gas & Electric?

The current wildfire crisis in California should serve as an object lesson in the folly of expecting private enterprise to operate in the service of the public interest. It’s common to hear ordinary taxpayers grousing about the DMV as a proxy for all that’s burdensome and irritating about bureaucracy.

[We] reached new levels of reliability and won recognition from our industry for our emergency response efforts.

But the electricity shutoffs across the state, aimed at reducing the chance that a spark from utility equipment will start a fire, are the handiwork of our private utilities, artifacts of their failure to spend more money on their infrastructure rather than shareholder dividends.

Federal Judge William Alsup of San Francisco, who is overseeing PG&E’s probation after its criminal conviction in connection with the 2010 gas line explosion that killed eight in San Bruno, implicitly acknowledged as much in an order last January. In his order, Alsup tasked the company to “remove or trim all trees that could fall onto its power lines” as well as “identify and fix all conductors that might swing together and arc ... under high-wind conditions,” among other steps that the company had been expected to take under existing law. Alsup observed that California fire authorities blamed PG&E for 18 wildfires in 2017 and referred 12 of them for possible criminal prosecution.

He wrote of the imperative to “protect the public from further wrongs” by PG&E and “deter similar wrongs from other utilities.” Alsup further noted “PG&E’s history of falsification of inspection reports.” PG&E argued that the order was so broad it would interfere with its operations.

In July, Alsup further criticized the company for spending on campaign contributions “even quite recently” and distributing $5 billion in shareholder dividends prior to filing for bankruptcy. He demanded to know why the company had made those expenditures instead of “replacing or repairing [its] aging transmission lines ... and removing or trimming the backlog of hazard trees.” PG&E replied that it engaged in the political process “to ensure that the concerns of customers, shareholders and employees are adequately represented before lawmakers and regulators,” and paid dividends to keep its shares desirable enough to allow it to raise money in the capital markets.

PG&E isn’t the only private company to be charged with breaching its duty to public service, although as the nation’s largest private utility its behavior stands out.

Nor is it the only private company to screw up. Within the universe of California electric companies alone, there’s Southern California Edison, whose ham-handed management of an $800-million refurbishment project at its San Onofre nuclear plant resulted in the permanent shutdown of the plant as much as 20 years ahead of its proper retirement.

Then there’s Facebook, a Silicon Valley behemoth whose insensitivity to its responsibilities to its users and society at large has become a byword. Earlier this month, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), a candidate for president, labeled Facebook a “disinformation-for-profit machine.” Given Facebook’s refusal to vet political ads for manifest untruths, not to mention its long history of breaches of users’ privacy, who could argue her point?

Facebook plainly sees the path to ever greater profits as one in which it tramples over the public interest; if its co-founder and chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, thinks he can get away with bowing to the public interest by giving speeches without taking concrete action, he will do so.

These cases point to our confusion over the proper role of government and private enterprise in our economy. Simply put, private enterprise invariably pursues its self-interest. There’s nothing wrong with that, within limits. The boundary line is where corporate self-interest conflicts with the public interest, and one duty of government is to monitor that line.

In the case of companies operating within natural monopolies, such as power distribution or cable television, government has a further responsibility to impose regulations to ensure that private enterprise doesn’t cross over it. Facebook is a different matter: The issue Warren raised touches on whether Facebook’s commercial footprint had grown so great that its impact on the public interest was a matter for public concern. (She has called for the company to be broken up.)

That’s why we have the Public Utilities Commissions and the Federal Communications Commission, not that they always function ideally (far from it).

The public sector has another important role in the economy. That’s to make investments that are needed in the community but that don’t directly offer an evident return to any given private company or investor.

To take one notable example: Hoover Dam. The dam was conceived to serve several purposes — to offer flood control and an irrigation supply for California’s Imperial Valley and to provide water and generate electricity for growing markets in California, Colorado and Arizona, among other places.

But electric companies didn’t want to pay for flood control and irrigation, and growers couldn’t afford to build a power-generating dam. So the federal government had to step in to build the all-purpose dam that eventually rose on the lower Colorado River — and that eventually produced billions of dollars in profit for all those private enterprises.

The development of the internet followed much the same pattern. In the late 1960s, Robert W. Taylor of the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (now the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA) perceived the need for a data transmission network that would be independent of mutually incompatible technologies owned by IBM and other firms, which all tried to squeeze profits out of their competing proprietary systems.

Meanwhile, the nation’s communications network was under the monopolistic thumb of AT&T, which obstructed efforts to use its phone lines to transmit data.

The solution was to build a government network, which evolved into the internet. Once the network matured, it was turned over to private companies, which by then could see quite a bit of potential profit in data transmission, thank you very much.

That brings us back to the wildfires. PG&E, as recent events have made clear, hasn’t sufficiently invested in its infrastructure for years, possibly because the company has not perceived a corporate imperative to do so.

That’s not to say the company hasn’t paid lip service to the public interest. In 2015, its then-CEO, Anthony F. Earley Jr., boasted that the company “took further steps to improve safety, reached new levels of reliability, and won recognition from our industry for our emergency response efforts. ... We strengthened the flexibility and resiliency of our system. And we sharpened our focus on achieving these gains while maintaining the affordability of our service.”

It’s proper to observe that at that moment, PG&E had gotten one huge wake-up call. The PUC had slapped the company with a record $1.6-billion penalty in connection with San Bruno. The money came out of its shareholders’ hides, reducing its profit that year to $874 million from more than $1.4 billion the previous year.

Yet it’s doubtful that anyone, from regulators to ratepayers, ever became completely convinced that the company had changed its ways. The subsequent fire seasons showed they were right to be skeptical.

It’s true that government authorities deserve plenty of blame for the disaster, and the disastrous performance of PG&E. They were the regulators, after all, and their record is one of indulgence toward a serial violator of laws and rules.

That still leaves us with the quandary of how to chart a path forward. With PG&E currently in bankruptcy, a battle for its assets (and soul) is being waged by Wall Street hedge funds.

As we’ve written, the eventual victor in this battle may pledge to honor the public interest, but that’s not the way to bet, for when management’s choice boils down to investment in infrastructure or another few pennies in dividends for shareholders, the financial incentives may tilt toward the latter.

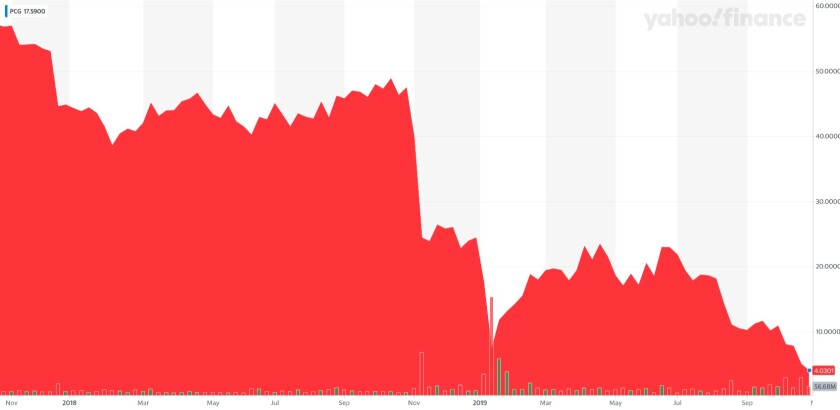

As we reported in January, the price of PG&E stock had fallen so low that buying the company outright was theoretically affordable for the state of California, which had an overall budget of more than $200 billion. Company shares were trading then at $17 and the whole company was worth less than $9 billion. With the company now in bankruptcy, PG&E shares are now trading at about $4 and the whole company could be had for just over $2 billion.

One argument against that move is that there’s no guarantee that state management would be better than private management. That’s possible, but PG&E’s successive managements haven’t left all that much room for lousier performance. Moreover, state ownership would at least place the public interest ahead of that of shareholders, since there wouldn’t be any shareholders.

The fundamental lesson of the wildfires remains in place. A private company’s responsibilities to the public interest will almost always take a back seat to the profit motive, unless it perceives that its profits are directly dependent on the public interest. But such direct connection is rare. The time may have come to turn over PG&E to government ownership, and see if its culture can be changed.