Articles Menu

Dec. 9. 2021

You’ve likely read a news story that opens with an anecdote.

Like the Global News report on the death of Benito Quesada, a 51-year-old father of four and employee of meat company Cargill. Quesada moved from Mexico to High River, Alberta, with his wife Maria Mendoza-Padron and their kids. On May 12, Quesada died from COVID-19-related complications after spending a significant amount of time in a medically induced coma.

“We haven’t touched anything,” his kids told Global News. “His boots are still in the entryway, his toothbrush, his cologne, everything is still there.”

Generally, this is where a news story will explain why this character’s experience is linked to a broader issue. It’ll use some data and expert voices to go a little deeper. By the end of the piece, the writer will have returned to the initial anecdote to provide a satisfying ending. This is a go-to method used by journalists, known as going “full circle.”

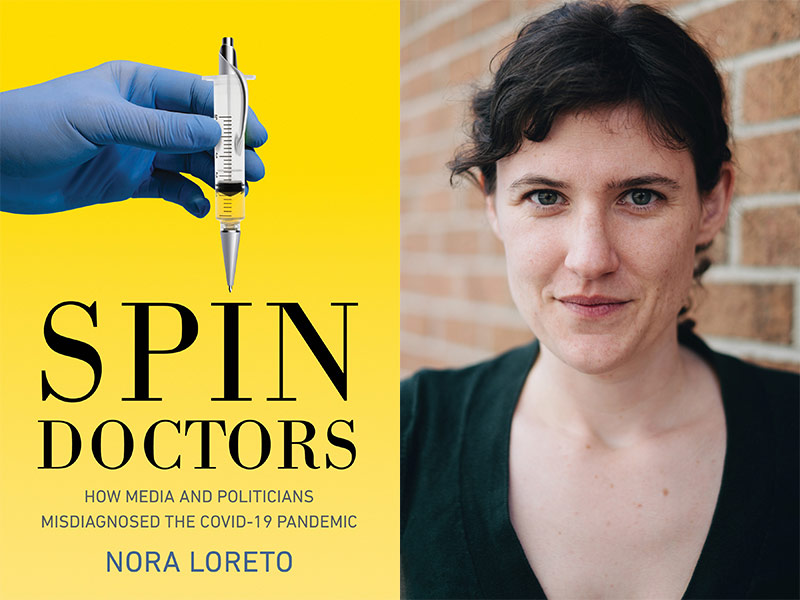

But Nora Loreto’s new book, Spin Doctors: How Media and Politicians Misdiagnosed the COVID-19 Pandemic, doesn’t circle back to the heartbreaking words of Quesada’s kids at the end of the chapter “COVID-19 Hits Food Processing Industries.”

Instead, Loreto pivots to a bigger picture: who and what was behind tragedies like Quesada’s.

“The way in which politicians treated food industry workers and the lack of attention journalists paid to these workers is deeply tied to the fact that a majority of these workers are not white,” she writes. “In ignoring so many racialized workers, politicians were rarely pressured to actually fix the issues.”

Spin Doctors relies not on one-off tragedies or impersonal statistics but rather a rhythmic and consistent approach to writing that couldn’t make the author’s argument any clearer: Canadian media failed to write stories that connected the country’s pandemic response to its own capitalistic impulses. And we are now paying the price.

In April 2020 Loreto began tracking, in a publicly shared spreadsheet, deaths in Canadian residential-care facilities, among health-care workers, in workplace outbreaks and other COVID outbreak-related deaths. The spreadsheet, last updated Dec. 3, tracks 18,639 residential facility deaths, 204 workplace outbreak deaths and 21 outbreak deaths.

Collecting the data for this spreadsheet put Loreto on the path to write a book about what critical and resourceful media — that doesn’t report every word out of a premier’s mouth as truth — can look like. If you’ve read 2020’s Take Back the Fight, her previous book, you see how themes of feminism, organizing and radicalizing a society fold perfectly into a book about a virus.

In chapters that cover how Canada’s COVID-19 response was informed by everything from systemic racism to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit’s inadequacy to injustice around migrant workers’ rights to ableism, Loreto uses Spin Doctors to ask and answer a variety of questions. Her inquiries hold Canadian media to account in the way media itself should’ve held politicians to account.

How did journalists fail to connect the dots between businesses thriving in COVID and profit-first premiers? Loreto asks. How did journalists fall into the trap of pitting back-to-school versus closing schools down arguments against each other, as if they were mutually exclusive options? How did journalists not think to speak to disabled experts, collect race-based data and avoid personal responsibility narratives, which benefited those in power?

Most readers will know that women were worse off in the pandemic in nearly every measure than men: exposure, unemployment and job losses were all higher.

But Loreto corrects a widely held belief that child care was the quintessential women’s issue. “Women were reduced to mothers,” she writes, with non-mothers erased entirely. Gendered violence increased in the first eight months of the pandemic. Sex workers, trans women and non-binary people seldom saw the light of day in news stories. And Canadian media failed to report on women’s issues through any sort of intersectional lens, Loreto writes. Women bore the brunt of the pandemic, journalists told Canada — and women sure did. But Canadian media didn’t tell us that not all women bore it equally.

Another stand-out chapter is “The Lie of Personal Responsibility.” Loreto paints a picture of what it must’ve been like for two women whose COVID-19 exposure was amplified by both being long-term care workers and staying at a shelter. “Is your bed far enough away from your neighbour’s?” she writes. “It doesn’t matter, you can’t move it anyway. Did the woman who used the bathroom before you have COVID-19? Did she clean the sink, wipe down the faucet? Even if she did, what about aerosol transmission? What’s the ventilation like?” Both these women, who found themselves on the frontlines of a pandemic as lowly paid, unhoused care workers, acquired COVID-19.

Responsible for bolstering the personal responsibility narrative, for example, might be one Huffington Post article which listed supposedly life-saving ways to avoid touching your face. “The message was clear,” writes Loreto. “The power to stop this pandemic is in your hands, as long as those hands don’t touch your face.”

Loreto does also share some rare examples of reporting that zeroed in on the structural issues driving pandemic effects. Like in the Ottawa Citizen, when emergency physician James Simpson warned that hospital overcrowding in Ontario due to a severe bed shortage in long-term care homes made patients “sitting ducks” to COVID-19 exposure.

But as Loreto tells me, one article doesn’t change the tide of national media focus.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: Spin Doctors is a timeless book. While reading, I was thinking how good it might be in schools and in classes. It’s a textbook, basically.

Nora Loreto: My entire inspiration was realizing how little common knowledge there was in Canada about the Spanish flu. How do we have this event that killed so many Canadians and there is literally no public remembrance? We’re always rediscovering, “Oh, they wore masks back then!” “Oh, they had problems with schools!” That cannot be allowed to happen with this pandemic. You can see the radicalization happening among different kinds of people in Canada, and how important it is for power to make sure that we do not fully understand what has just happened. And that process of forgetting has already happened.

What do you think was media’s biggest mistake when it comes to covering long-term care?

Long-term care was an afterthought. This is the thing that was so shocking to me at the time. When you go back to look at who was writing what on long-term care in February, it was nothing. If you look at what was coming out of the World Health Organization, what was coming out of China, it was clear that congregate living facilities were going to be a disaster.

It kind of suggests to me that if you’re of a certain class, if you’re a certain race in this country, you are not likely very far away from someone who lives or works within long-term care. And most journalists are not that. Politicians are certainly not that. And so I think that this is one of the really good examples of how it’s an invisible life system based on class. And the real heart of this becomes a question of disability chauvinism, of ableism, of bigotry.

Another media focus in 2020 was whether getting rid of for-profit care would solve the problems we were seeing in long-term care. I’m curious what you think about that conversational focus.

It ignores the fact that the public system is not much better, right? It isn’t as simple as saying the public system will be fine, because governments all across the country are incapable of doing the right thing. By making something public, you’re giving it to the government to hopefully do the right thing.

It’s a question of public control. These institutions need to be democratically controlled. There needs to be actual family and resident input to how they’re run. This is a system that needs to be brought into the health-care system. So that makes it de facto nationalized. But even that is a huge debate. There’s not a consensus on the left.

One thing we witnessed during the pandemic was a lack of data. Government didn’t provide comprehensive data on things like race-based deaths, deaths in long-term care homes and workplace outbreaks. What do you recommend to journalists or newsrooms looking to rely less on government data?

We need to come up with our own data. I’ve had a lot of debates with other journalists about whether or not this is even something journalists should do, or if we should be able to rely on public data. When you default to government data, you will always miss anomalies. There’s too much desire from governments to not have the whole story told. And then when you start to present this data to government, then you start to see, “Oh, there’s actually a disconnect here in how government understands.” We need to be both fighting for better data but also keeping track of our own data, recognizing that the state has an interest in suppressing data.

The narrative around “essential work” plays a huge role in Spin Doctors. It was kind of a character on its own: this arbitrary decision of what was and wasn’t essential. How did that narrative factor into whose safety was prioritized and whose wasn’t?

The essential work narrative was poison. It was caustic. And I quote Harsha Walia in the book: “they’re essential to capitalism.” That’s what we mean when we say they’re essential. I don’t think Canadians look at people who are doing frontline work, let’s say in the food industries, and say, “Well, they’re disposable.” We are led to believe that through all the ways that society treats them through salaries and precarity.

The pandemic was this moment where everybody had this chance to say, “Wow, actually, I depend on these workers.” I think this could have been a very radical moment for essential workers to find solidarity from, let’s say, non-critical, non-essential workers, from those working from home. I think it’s really important to note too, that I’m the only person in Canada that has done work trying to track deaths related to workplaces. It’s like, are you kidding me?

In June 2020, Black Lives Matter made waves by humanizing the people who are victims of police brutality, like George Floyd and Regis Korchinski-Paquet. It helped a lot of people understand the idea of defunding the police. There were so many humanizing stories around COVID-19 impacting certain communities. Why weren’t the evidence and anecdotes enough to radicalize? What’s the difference there?

You can’t just show an individual a car crash and then make them understand how to stop a car crash. You can show them a car crash and they’ll go, “Oh, that’s terrible. I don’t want to go through that myself.” They’re not like, “I wonder what the speed was, and if the lighting was any good, and if there’s a guardrail.” That’s what we lose when we zoom in too closely on these tragedies. Journalism in Canada is so oriented towards telling stories like that. You have these crushingly sad stories. A couple both got COVID; they own a corner store; everybody loves them; then they die. This is a story from Ottawa. And then what? You’re paralyzed by how sad it is and there’s nothing that comes out of it that makes you say, “Well, I’m ready to go pick up a pitchfork and head toward my local barricade.”

Let’s say the coverage did do that. Then there’s a total lack of possible paths for action. Because, again, you don’t witness a car crash and then say, “OK, now I’m going to organize my neighbourhood to ban cars.”

That’s where you need organizers. The real question becomes, where are those fucking people? The Black Lives Matter mobilizations were great because it was this moment where a lot of people, especially young people, were saying, “OK, there’s a pandemic on, it seems like it’s OK to be outside — we’re going to do this because it’s important. Wear your masks, let’s see what happens.”

Why do you think child care became the go-to issue for women’s pandemic issues?

I honestly think that it was because there’s a critical mass of young women journalists who were trying to be journalists with kids at home. Actually, men too. I don’t think it was much more complicated than that. I think the Liberals seized on it — they knew that this was something that they could promise. Had there not been the Liberal support for this, I don’t think it would have gotten as much attention either.

Some coverage that questioned the safety of vaccines propagated the idea that they were made too quickly, resulting in a lot of suspicion-raising headlines. What was more dangerous: a lack of science and vaccine literacy among journalists? Or a lack of media literacy among the Canadian public?

I think it’s science literacy with journalists, and I think it’s also journalists trying to chase clicks, to be honest. Every time there was a survey that came out in April 2020 that asked “Would you take a vaccine?” it was like, why are you publishing this? There is no vaccine. How can you reasonably expect someone to answer that question? They’re either going to say “I’ll take anything” or they’ll be like “Are you nuts?”

The incredible scientific breakthrough that was RNA technology — that should have been the most welcomed and celebrated news of 2020. And not because it was going to solve the pandemic. But because this was an incredible technological advance. This is what happens when the global scientific community is literally oriented towards a single goal — we can come up with some really incredible advances. Instead, it was always covered from the perspective of the assumption that safety will be compromised.

How different would our pandemic response have looked if we had been looking more to experts who have disabilities? If we had more disabled journalists? These are questions you pose in the book.

I answer that question by talking about what other disability activists say: If you had listened to us, you would have been better prepared for infection control; you would have been more ready to live in isolation; we would have talked about long-term care as a site of disability rather than a site of age. That’s the narrative side. On the policy side, if you had looked at the people who were the most at risk as being people who are disabled, long-term care would have entered the conversation far earlier than after people were already dying.

At the beginning of Spin Doctors, you write that if an optimistic reader doesn’t make it to the end of this very long book, “Don’t worry about it!” For those who might not reach the end of the book, can you share its final call to action?

It is this: Maybe you weren’t aware of this stuff before the pandemic. And now you are. We can’t claim that we didn’t know the ravages of capitalism and colonialism. So now that we know, what do we do about it?

What you do about it depends on who you are. If you are someone who holds a position of power, you better be using that power to challenge power. If you’re a progressive politician, you better be doing everything in your power to change power. If you’re a community organizer, you’re probably doing this already. But you have to find ways to bring new people along.

If you’re waiting for someone else to do this stuff, it’s not going to happen. You have to be the one to take initial steps. We all have a responsibility to do something. And it can be big or it can be extremely local and very small. The system requires us all to be isolated and refusing to be in any contact with one another.

We need to refuse that. Wherever you’re located, you should be building that community, however you can.

[Top photo: Ambulances arrive at Surrey Memorial Hospital on April 2, 2020. Photo by Joshua Berson.]