Articles Menu

May 17, 2020

One might have hoped that the very severity of the threat posed by the pandemic would compel the elites who manage capitalist societies to behave more responsibly and decently. The return of the pre-neoliberal “nanny state” (however inadequate it was) seemed to some a real possibility. But while the capitalist state may be concerned with maintaining social equilibrium, preserving a basic level of public health and upholding its own legitimacy, it remains utterly devoted to ensuring the conditions in which businesses can function and profits can continue to flow.

It is not surprising, then, that belated and grudging measures to keep people distanced and safe are getting sidelined by the determination to reopen economies—at considerable risk to vast numbers of people. It is also to be expected that limited forms of social protection, such as suspending evictions or granting emergency payments to those without income, will give way to renewed and intensified measures of austerity.

We are passing through a period that is disrupting the lives of hundreds of millions of people and shaking up their thinking profoundly. A sense of grievance and discontent can take hold in such a situation. The obvious lack of preparedness for the pandemic, the fact that healthcare systems had been weakened by decades of austerity and that vulnerable sections of the population were left unprotected are glaring failures and injustices, which are triggering widespread and volatile anger.

According to a recent EKOS poll, 73 percent of people in Canada expect there to be a “broad transformation of our society” as a result of the pandemic, with a majority calling for major reforms that dramatically improve “health and well being.” These findings are predictable enough in light of the sudden hardships and obstacles people are experiencing right now. However, we need to recognize that any widely shared hopes for sweeping change are likely to run up against a developing political agenda that moves in the very opposite direction.

The present lockdown may not be the last of its kind and the pandemic will remain a source of economic dislocation for some time yet. Moreover, the “V-shaped recovery” that political leaders and central banks hope for is not in the cards. Very severe unemployment is likely to persist for a long time. Emergency spending by governments, including vast corporate bailouts, will lead to fiscal crisis and merciless social cutbacks. The aspirations expressed in the EKOS poll stand a chance of being realized only on condition of a major social mobilization and determined struggle.

In the coming days, months and years, however, as working class people face major attacks in the wake of the pandemic, they will also be armed with the knowledge that the Thatcherite mantra “there is no alternative” was given the lie by some of the very policies adopted by governments during the health crisis. Everyone will know that it is possible to suspend some of the normal workings of a market system and increase the level of state intervention. It is possible to allocate massive resources in ways that contradict economic orthodoxy which has it that deficits are an absolute barrier to meeting urgent needs.

However inconsistently, reluctantly and temporarily governments enacted such “subversive” measures, the cat is out of the bag. In this context, it is entirely likely that mass opposition to a renewed and relentless assault on working class living standards will emerge. At every turn, the extraordinary moment in history we are living through can reinforce the dawning awareness, captured by the EKOS poll, that things can’t go on as before and must change for the better. In several key areas, demands can be advanced, backed by mass action and campaigns, which challenge regressive responses to the crisis.

When it comes to workers’ rights and the rate of exploitation, the imperatives of capital and the aspirations of working people are on a collision course. In conditions of mass unemployment and stubborn economic downturn, employers will seek to expand and intensify their pursuit of the neoliberal strategy of expanding the just-in-time precarious workforce with few rights and poverty wages. However, the risks and hardships faced by essential workers during the pandemic will leave deep resentment and anger. Workers in health care, the service sector, meat processing plants and other front line occupations, will know that, empty rhetoric about their heroism notwithstanding, they have had a very raw deal.

A counter offensive to the employers’ attack in the form of demands for living wages, secure employment and workplace rights could be enormously powerful and enjoy massive support—all the more so, because this struggle for the rights of precarious low paid workers is bound up with the challenge to racism in Canadian society. The sharply disproportionate place occupied by racialized workers in the ranks of the super exploited ensures that this is so.

Income support systems have been gutted during the neoliberal decades and massive numbers of people entered the lockdowns without an adequate replacement for lost wages. Round after round of cutbacks to Canada’s unemployment insurance program and its provincial social assistance systems left hundreds of thousands in a dire situation. The hastily improvised Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) has only partly compensated for this. I don’t support the notion that a basic income would provide a progressive alternative to existing forms of income support, but there is no doubt that the period of widespread unemployment that lies ahead will create the absolute necessity for mass social action with the immediate goal of ensuring that federal and provincial benefit systems are accessible and adequate. Such a struggle must be taken up simply to avoid pain, suffering and destitution on a scale unseen since the Great Depression.

The lockdown has seen governments forced to take some action to prevent the eviction of tenants who were unable to pay their rent. However, at present in Toronto, landlords and their agents are going door to door with debit machines trying to bully tenants into handing over what little income they have for food to cover rental arrears. Organized resistance has begun, with widespread rent strikes. However, once this first lockdown comes to an end, there will be huge numbers of people who owe several months rent and who remain jobless. The demand for a rent and mortgage freeze, along with an end to economic evictions, will be a vital question for many on the edge of losing their housing.

The issue of housing, however, goes well beyond the immediate question of evictions. In recent decades, urban space has been reorganized in accordance with the dictates of the neoliberal city. The extreme commodification of housing has driven up home purchase prices and rents to impossible levels, while dumping homeless people on the streets. A developer-led housing system has become a crippling liability. The demand for real non-market housing options must be pressed and housing for all treated as a human right.

The pandemic has struck those who are the most vulnerable, and one of its deadliest manifestations has been its lethal impact on the residents and workers of long term care facilities. Those who have been turned over to private operators and run for profit have been far and away the most deadly. A stunning 82 percent of COVID-19 deaths in Canada have occurred in long-term care residences. The demand must be that these for profit death traps be taken out of the hands of the private sector and run as public institutions. Nor can the degraded condition of public healthcare systems, that greatly exacerbated the vulnerability of populations to COVID-19, be overlooked or tolerated. Far from accepting the further undermining of public healthcare, the pervasive sentiment for change expressed in that EKOS poll must find its expression in mass social action to demand an end to “hallway medicine” and the creation of facilities and staffing levels sufficient to meet the needs of communities.

The social and economic system at the root of this pandemic will seek to transfer the cost of the ongoing crisis to working class people. The current and future attacks by the political agents of the ruling class will have to be driven back, and resistance may gain momentum with the impact of the coronavirus, the lockdown and the resulting economic shocks. Indeed, the COVID-19 crisis has intensified a mood of grievance and outrage that found expression last year in the wave of global protests against the neoliberal order.

The possibilities of going much further are multiplying. Take for example the pressure from both the rank and file and the broader community that led to GM producing one million masks per month for health care workers at its closed plant in Oshawa. That plant could be nationalized and permanently retooled to produce personal protective and other medical equipment.

In the post-pandemic period, we need mass movements that go beyond protesting cuts in an effort merely to impede the advance of a regressive agenda. We need to build on the sentiment underlying the findings of the EKOS poll and make demands based on the needs of working class people, even if they may ultimately be impossible to win under capitalism. If we think and act along these lines, the defensive strategies that marked the neoliberal decades may yield to a more militant and radical approach that poses the question of a “broad transformation of our society.”

John Clarke is a writer and retired organizer for the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP). Follow his tweets at @JohnOCAP and blog at johnclarkeblog.com.

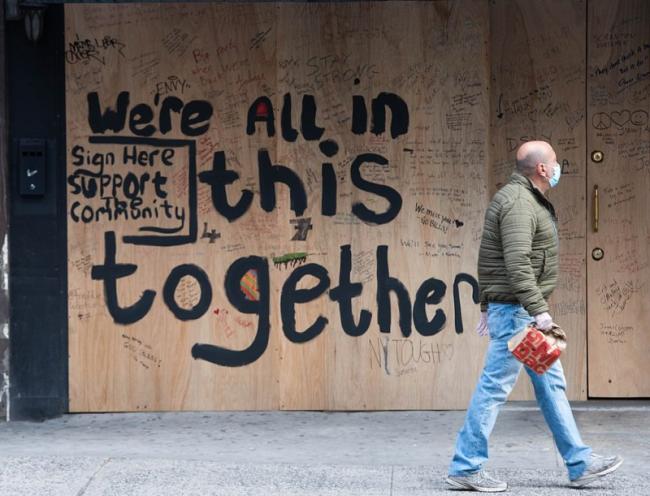

[Top photo: Graffiti adorns a boarded-up restaurant in New York City. Photo by Anthony Quintano/Flickr.]