Articles Menu

Feb. 10, 2023

When the Blueberry River First Nations took the provincial government to court in March 2015, arguing that cumulative industrial developments had robbed them of their ability to hunt and fish, oil and gas companies could see trouble lay ahead.

So what did they do? They doubled down with a surge of new development proposals each of which the provincial government quickly signed off on well before the court issued its decision.

The most aggressive company was Petronas, the state-owned Malaysian multinational that holds rights to drill and frack over a wider area than any other fossil fuel company operating in British Columbia. Petronas is also a major partner (second only to Shell) in LNG Canada, the massive $40-billion methane gas liquification facility under construction at Kitimat.

That plant is destined to take methane gas drilled and fracked in Blueberry River First Nations’ territory and super-cool it to liquid form prior to pumping it into the cavernous holds of ocean tankers for transport. And there’s a lot at stake for Petronas in that enterprise. By 2025 or so, it will have to start pumping massive amounts of methane gas to Kitimat each year.

Much of that methane will come from the Montney Formation, a deep zone of shale rock underlying much of the Peace River region, which is covered by Treaty 8, a document that the Blueberry River First Nations among others signed well over a century ago. To get that methane, companies must build large “multi-well pads,” each several acres in size.

Each pad, which is also associated with connecting roads and pipeline corridors that further fragment the land causing harm to moose and other wildlife, can accommodate two dozen or more gas wells. After all those wells are drilled, they are then fracked: a process where immense quantities of water, sand and chemicals are blasted underground with earthquake-inducing force to “liberate” the trapped gas.

Skyrocketing approvals

In the seven years before the Blueberry River First Nations (Blueberry River) went to court, BC’s Oil and Gas Commission — the fossil fuel industry’s “one-stop shop” for regulatory approvals — issued Petronas an average of four multi-well pad approvals each year.

In 2016, the first full year the matter was before the court, the number of such approvals skyrocketed. Petronas received 35 multi-well pad approvals that year. The Oil and Gas Commission would issue Petronas 73 more the following year, which the BC Supreme Court later concluded was done without a thought given to cumulative effects.

No other oil and gas company received remotely close to as many approvals, although Tourmaline, another major operator in Blueberry River territory, is of note. It received just under three permits per year prior to the court case, but 27 in 2016 and another 25 in 2019.

That tsunami of industry applications and routine government authorizations is critical to understanding the landmark ruling by B.C. Supreme Court Justice Emily Burke in June 2021. Her ruling found that the cumulative effect of multiple industrial developments — all authorized by the provincial government — had clearly violated Blueberry River’s treaty rights.

That ruling brought new resource industry development approvals to a halt pending negotiations between the provincial government and Blueberry River, which ended this January in what both parties call a “historic” agreement.

The agreement was jointly announced last month in Prince George midway through a week-long resource industries conference. Premier David Eby and Blueberry River First Nations Chief Judy Desjarlais formally signed the document as no less than five provincial cabinet members looked on.

Eby then took to the podium to talk about what brought the parties to the negotiating table.

“In June of 2021, the B.C. Supreme Court found that the government had breached Treaty 8 as Blueberry River First Nations could no longer meaningfully exercise their treaty rights as a result of the cumulative impacts of resource development. Government had an option. We could appeal the decision, leading to years of battling through the courts and a likely injunction paralyzing activity on the ground for an indeterminate time,” the premier said. “We decided to take another approach — to meaningfully address this challenge in partnership.”

When the announcement was over and the few reporters attending the event in person or by phone asked questions, no one pressed the premier on this point.

Choice or necessity for the provincial government?

As then-attorney general, it was Eby’s job to read Justice Burke’s ruling and decide whether or not the government would appeal.

Burke was scathing in her portrayal of provincial agencies like the Oil and Gas Commission, which only once in its 20-plus years of existence had turned down a development application despite having received hundreds of thousands of such applications over the years. Not only that, Burke noted that the commission didn’t even include a consideration of treaty rights in its so-called area-based analysis of oil and gas industry activities.

Eby knew that appealing the decision courted an injunction that could put an indefinite hold on new developments in Blueberry River territory, and that was simply not in the cards for a government that was all-in on LNG.

Eby’s decision to “choose negotiation over litigation” wasn’t a choice so much as a necessity for a government that had boasted of B.C.’s “unlimited potential” to supply “clean” natural gas to the world and had provided a raft of subsidies to the proponents of the LNG Canada plant.

The critical question now is what does the agreement actually do by way of limiting natural gas developments in Blueberry River territory?

Sadly, the answer appears to be not a lot, although some of this must be inferred because both parties to the agreement are keeping it to themselves.

So we are left with the scant details in the provincial government’s press release and other details in media accounts written by people who received a technical briefing.

A gaping hole

Limited as that information is, it suggests that for some time to come fossil fuel companies will not face serious hurdles to proceed with planned extraction. Perhaps the most important detail to emerge following the announcement is that Petronas and other companies will be able to focus their future activities “in areas already developed” within Blueberry River territory.

This is a gaping hole that thousands of trucks carrying drilling equipment or the water, sand and chemicals used in the fracking process will be able to barrel through.

The multi-well pads authorized to Petronas and Tourmaline alone between 2015 and 2020 amount to 187. Assuming that each one of those pads can accommodate two dozen wells, that amounts to 4,488 methane gas wells, the majority of which will be on lands in Blueberry River territory.

Allan Chapman, a professional hydrologist who once was the most senior water scientist with the Oil and Gas Commission and is now a consultant, estimates that the existing unused capacity on the well pads already cleared in northeast B.C. provides for decades more drilling and fracking.

To estimate the “unused capacity” associated with multi-well pads already on the landscape, Chapman assumed that on average 24 wells could be drilled and fracked per pad.

“The actual number could be higher,” Chapman says. “Some pads are showing as many as 30 wells on a pad. But, at 24 wells per pad there is ‘unused capacity’ of 13,000 wells.”

That represents a combined 25 years of drilling and fracking in areas “already developed” within Blueberry River territory or that of neighbouring First Nations who, like Blueberry River, signed Treaty 8.

It also means, as Chapman detailed in a peer-reviewed journal article, that many more earthquakes induced by fracking lie ahead in Blueberry River territory and that the cumulative effect of pumping billions of litres of water into the earth will also trigger higher magnitude earthquakes.

The big buildout

In 2015, only months after the Blueberry River First Nations launched their court case, I travelled north from Fort St. John on the Alaska Highway for about two hours to visit a landowner who lived in a remote home not far from where the highway makes its dramatic descent to the Sikanni Chief River.

For the next two hours we drove down wide gravel roads that had fragmented the once moose-rich boreal forest and that could easily accommodate two-way traffic by 18-wheel trucks.

Petronas had cut down tens of thousands of trees to make those roads possible and tens of thousands more to make way for future pipelines, compressor stations, water storage pits and wastewater ponds and well pads.

It wasn’t the scale of it all that made such an impression — as what it portended.

I had seen something like this once before in the late 1980s in Oaxaca state in Mexico: boulevards and zócalos, or town squares, lined with iron lampposts carved out of the forests ringing nine bays in the Huatulco area on the Pacific coast. Except no buildings lined them.

The boulevards and zócalos were a prelude to what was to come — luxury hotels, spas and shops — part of a plan by the Mexican government to push Indigenous fishing communities out and turn the region into a tourist destination modelled on Cancun.

This is what happens the world over when governments are wooed by would-be investors with promises of resource rents and tax dollars.

On subsequent visits to Blueberry River territory in 2017 and again in 2019, I saw Petronas reach ever deeper into the boreal forest as it built a number of dams (many in violation of provincial regulations as it turned out and for which the company was never charged) to capture freshwater used in fracking operations.

There were also dozens of big, excavated water pits alongside the roads, dug to hold water also used in the fracking process. And periodically there were even bigger pits sunk far deeper into the earth. These excavations were then lined in layers of thick, black industrial plastic and filled with orangey-brown wastewater, the toxic legacy of the fracking process.

Unanswered questions

All of this and more was “already developed” before Justice Burke wrote her ruling and is where Petronas and other companies will comfortably be able to operate for years to come.

An unanswered question is what it will mean for Petronas and other fracking companies when it comes to expanding this sprawling network of well pads, roads, compressor stations and pipeline corridors.

Again, we have no details because the agreement has not been made public. In news stories after the agreement was signed, however, it was reported that the industry would be held to “reducing new disturbances by 50 per cent from pre-court decision years.”

Here, the devil will be in the details. What year? Will it be the pre-court decision year of 2015, when Petronas was granted three multi-well approvals, or the pre-court decision year of 2016 when it was granted 35, or the pre-court decision year of 2017 when it received 73?

Will the restrictions apply to the sheer number of development applications and approvals or to the total area of new land disturbed?

Such questions matter, because as Justice Burke noted in her decision “85 per cent of the Blueberry claim area is within 250 metres of a disturbance, and 91 per cent of the Blueberry claim area is within 500 metres of a disturbance.”

Every new road, every new pipeline corridor, every new flare stack, every new compressor station, every new wastewater pit and every new well pad will make that fragmented landscape ever more terribly broken than it already is.

Notably absent in the materials released by the provincial government and subsequently reported on is any mention that Petronas or other fossil fuel companies operating in the Blueberry River First Nations’ claim area will lose any of the “subsurface rights” that they were granted by the provincial government in exchange for paying the government billions of dollars.

The same does not appear to be the case for the forest industry, however, which is expected to lose access to some forests that are either already logged or slated to be logged in Blueberry River territory. For this, the forest company or companies will be compensated, as logging company Interfor recently was, when the provincial government announced that it was protecting a tract of interior temperate rainforest.

Underscoring the likelihood that for at least the time being, the fossil fuel companies are not taking a hit was a hint contained in the government’s press release, which included supportive quotes from Petronas, Tourmaline and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

Proceeding with pace

Izwan Ismail, president and CEO of Petronas Energy Canada Ltd., also spoke at the signing ceremony, making it clear that now that the agreement is signed it’s back to business.

“Time is of essence to move forward with important investments in clean technology and innovation, including the sustainable development of natural gas and LNG so that Canada remains an important player in the global energy transition,” Ismail said as Eby and Chief Desjarlais looked on. “I feel with this important agreement in place and a plan to manage cumulative impacts, it is our expectation that now the necessary work can proceed at pace.”

Key components of the agreement included in the government’s press release note that:

Blueberry River will also receive $87.5 million over three years plus additional money in the form of a greater share of the royalty payments made to the provincial government by the fossil fuel industry when it produces methane gas in Blueberry River territory. Which is as it should be. First Nations should be compensated if and when they consent to industrial activity in their territories. And when they are compensated, it should be as true 50/50 partners.

“It’s been a long battle of protecting our treaty rights to get here,” Chief Desjarlais said following Eby’s remarks. “For generations, our people have watched as the land of which our way of life depends be broken apart piece by piece.”

Chief Desjarlais went on to say that this breaking began in her grandmother’s time and soon meant that “our members were unable to live off the land and practice their way of life as promised in our treaty.”

She added that the agreement ensures that “First Nations will be participants in all stages of development. Blueberry now has a say every step of the way, starting at the pre-engagement phase.”

“The main principle of our treaty was to ensure Blueberry was able to practice our way of life for as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the rivers flow. And a precedent has been set. From this day forward, our cultural and traditional values will come before anything else,” Chief Desjarlais said.

But how, exactly, this will square with an onslaught of new drilling and fracking remains to be seen. The long battle is not over. It’s just shifting to a new front.

Ben Parfitt is resource policy analyst for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives B.C. office.

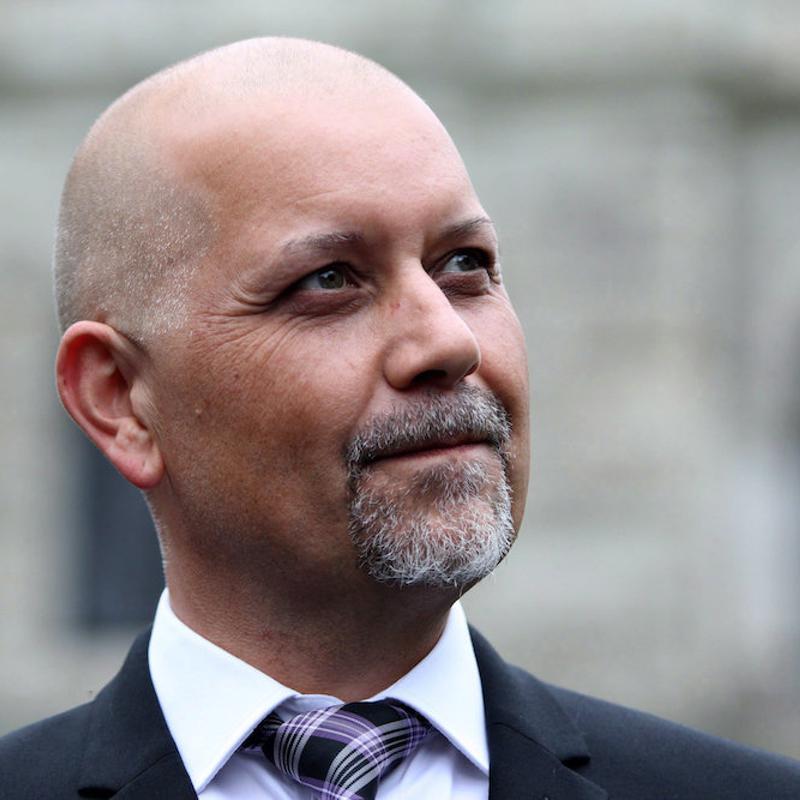

[Top photo: Blueberry First Nations Chief Judy Desjarlais, centre, signed a historic partnership agreement last month with BC’s Energy Minister Josie Osborne, left, and Premier David Eby, right. But it comes after years of ramped up gas extraction. Photo via BC government Flickr.]