Articles Menu

Oct. 9, 2025

s drought in British Columbia’s Peace River region leads to massive wildfires and the City of Dawson Creek scrambles to find a new water source, a report released today concludes that water use by the region’s fracking industry shot up a record 50 per cent last year.

That surge, warns Stand.earth, is only the beginning, given the province’s newfound status as an international gas exporter and with government and industry plans calling for even more processing and exporting facilities in the future.

“Earlier this year, the first liquefied natural gas export terminal in Canada, LNG Canada, came online, creating a new demand for fracked gas from B.C.’s Peace River region,” the report states.

“As the number of new fracking wells surges to meet increased demand, we are beginning to see even more social and environmental impacts to the communities in the Peace River region due to resource extraction.”

The Stand.earth report relies on water use data collected by the BC Energy Regulator, or BCER, formerly known as the BC Oil and Gas Commission.

The data is focused only on the water that the industry uses under short-term water permits and water licences issued by the regulator.

The regulator’s water reports don’t include water purchased from private sources. That may include water from an extensive network of dugouts and dams purpose-built to capture surface water and groundwater, as well as wastewater generated at fracking operations and sometimes reused.

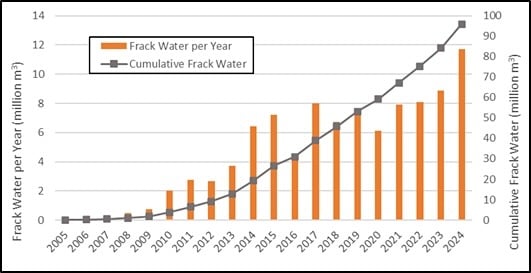

Despite its limitations, the regulator’s reporting shows that oil and gas industry water use under short-term and long-term authorizations leapt from just over six million cubic metres in 2023 to more than nine million cubic metres in 2024, an amount great enough to submerge nearly 1,700 football fields under a metre of water.

The industry’s skyrocketing water use is playing out against the backdrop of drought in Dawson Creek and its surrounding rural enclaves. The area has experienced drought in three successive years and in four of the past five.

“Increased competition for water, which has been exacerbated by a prolonged drought in the region, threatens both the agricultural sector and communities’ access to drinking water,” Stand.earth warns in its report. “The most alarming example of this is in Dawson Creek, where city officials are scrambling to find new sources for municipal drinking water because their current source, the Kiskatinaw River, has nearly run dry.”

As reported recently by The Tyee, the Kiskatinaw’s water levels are perilously low, lower than at any point since records were kept.

The Kiskatinaw is Dawson Creek’s only water source, and its current condition, which shows little sign of improving, has prompted city officials to come up with a proposal to pipe water from the Peace River more than 50 kilometres away.

The city is seeking access to 10 million cubic metres of water per year. If the provincial government, which is aggressively promoting more LNG production and exports from B.C., grants that request, it would give Dawson Creek access to three times more water than it needs for community use.

The city made it clear in its application to B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office that this would open the door to it selling water to the fracking industry, which would help it to offset its infrastructure costs.

The oil and gas industry uses massive amounts of water. For fracking, water is combined with sand and chemicals and pumped underground at earthquake-inducing pressure to fracture rock formations and allow the trapped hydrocarbons to be released.

The trackable nine million cubic metres of fresh water that the BCER reported the industry used in its fracking operations last year was the “equivalent of the household water needs of 111,530 Canadians — or the entire population of the City of Nanaimo,” the Stand.earth report says.

Water use increases as fracking technology improves

As reported previously by The Tyee’s Andrew Nikiforuk, respected energy analyst David Hughes has warned that advancements in fracking technology mean that companies are drilling much longer wells. The wells are drilled straight down until they reach the targeted oil-and-gas-bearing rock formations, prior to the drilling direction being reoriented horizontally. The horizontal bores are then fracked in stages from the farthest to nearest ends.

As the horizontal bores have increased in length, so have the number of discreet fracking operations per well.

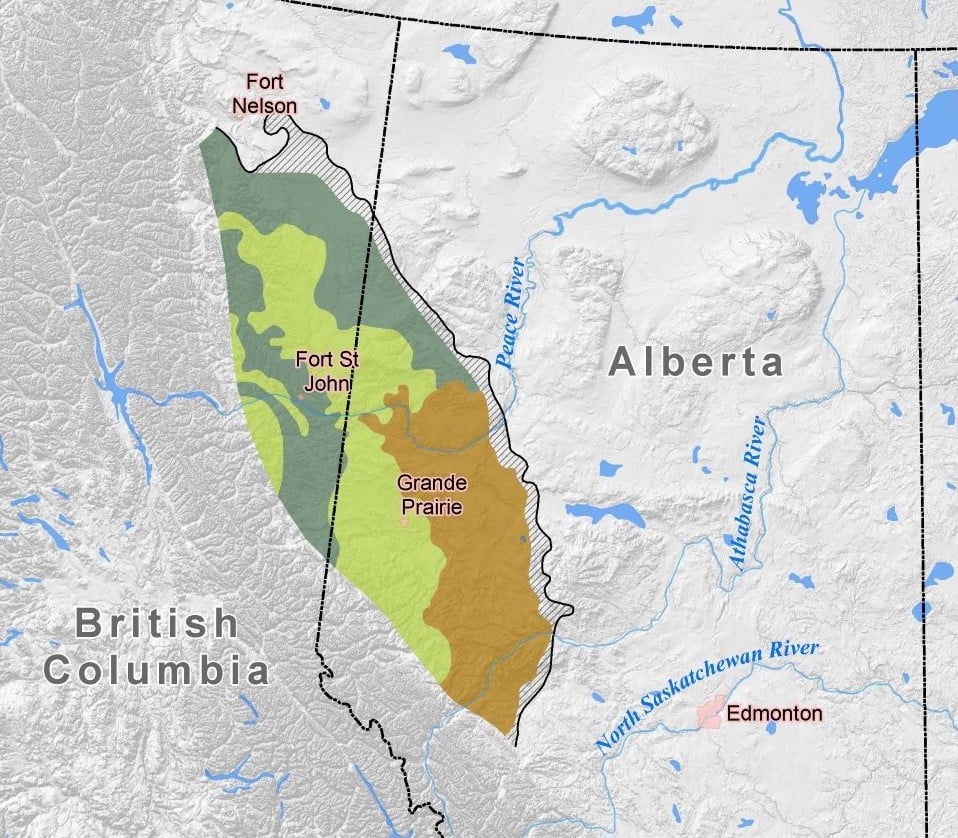

As Hughes reported, the length of horizontal well bores in the Montney formation, which underlies Dawson Creek, Fort St. John and other Peace River communities, is now 2.7 kilometres on average — roughly the distance between Vancouver’s Stanley Park and Rogers Arena.

“Water injection intensity has increased 45 per cent to an average of 8,346 litres per metre and an average well now consumes 23.1 million litres, a 10-fold increase since 2010,” Hughes concludes.

Allan Chapman, a former hydrologist with the oil and gas commission, has also examined water use in the fracking industry.

In a peer-reviewed paper published in the Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection in 2021, Chapman presented data documenting the steady rise in frack water use per well year over year, from less than 3,000 cubic metres per well in 2008 to almost 20,000 cubic metres per well in 2021. Chapman also forecast just how much water would be needed to meet just the needs of the 639 existing “multi-well” gas pads that existed at that time in the B.C. portion of the Montney.

Each of those pads had, on average, just four wells drilled and fracked on them, leaving room for at least another 16 wells per pad.

Chapman reported that it would take the “equivalent water volume of 100,000 Olympic-size swimming pools” just to drill and frack all of those additional wells. That’s 250 million cubic metres of water, which expressed another way would be like submerging the entire city of Vancouver under roughly 2.2 metres of water.

In the ensuing four years since that report was published, many more new well pads have also been added to the mix, upping the amount of water that will be needed in future years to keep the fracking industry going.

The average water use per well increased to almost 24,000 cubic metres by 2024, according to figures contained in a database maintained by the BCER and known as FracFocus. That represents an increase of 20 per cent in water use by the fracking industry in just three years since Chapman’s report of 2021.

The FracFocus database shows that the total water pumped underground at fracked wells in B.C. in 2024 was 11.7 million cubic metres, roughly 30 per cent more than what the BCER reports in its annual water use summary for last year. This is because the BCER’s water use reports cover only the water withdrawn under the short-term permits and longer-term water licences issued by the BCER under the Water Sustainability Act to fracking companies.

The additional 30 per cent may include water purchased from landowners and private companies as well as “flowback” or “recycled” wastewater that is highly toxic and is captured by oil and gas companies at well bore heads following fracking.

Hughes suggests a possible doubling of well drilling and fracking in the coming few years to feed LNG Canada, with an annual water demand double or triple its current level.

The BC Energy Regulator’s response

The Tyee filed a number of questions with the BCER and received emailed responses.

Confusingly, the regulator provided figures on the industry’s water use that contradicted its own published figures on water use.

The BCER told The Tyee that roughly one year ago, in August 2024, it directed the fracking industry to differentiate between the recycled water it used in fracking operations and the fresh water it used.

“Data collected from August to December 2024 indicates approximately 68 per cent of the total fluid volume used was saline [recycled], with the remainder non-saline [fresh]. This is approximately 1.5 million m3 of freshwater and 3.4 million m3 of recycled water in northeast B.C. in 2024,” the BCER told The Tyee.

In a subsequent emailed clarification, the BCER said that in total in 2024 the oil and gas industry used “approximately 14 million cubic metres of water in fracking.” This included more than nine million cubic metres of fresh water withdrawn from rivers, lakes and streams under BCER-approved short-term water permits and long-term water licences, some of which was used in other industrial activities, including water used for gas drilling, water sprayed on roads for dust control and water used for ice road freezing.

In response to questions The Tyee sent about how the BCER factors drought into its water permissions for the industry, the BCER said that it “actively monitors” water basins across the province. That includes focusing on specific water sources that may be “stressed.” This may mean not authorizing water withdrawals on certain stressed rivers or creeks, such as the Kiskatinaw, and possibly issuing orders to companies to suspend water withdrawals under licences or permits issued to them because of low water flows, the BCER said.

“Each water use application is reviewed carefully so that the B.C. Environmental Flow Needs (EFN) Policy is adhered to conservatively to ensure there are minimal impacts to the environment and other [water] users,” the BCER said.

The BCER also said the fracking industry’s water use in 2024 was “a fraction of what is authorized for use” and that water licences may have flow thresholds embedded in them “whereby withdrawal cannot occur when streamflow reaches or drops below that value.”

Unlike with water licences, Chapman notes that short-term water use permits issued by the regulator do not have comparable low-flow environmental flow thresholds. The water used by fracking companies under such permits has increased significantly, according to the data used in the Stand.earth report and subsequently analyzed by The Tyee.

Stand.earth calls on province to increase water fees

Stand.earth notes in its report that Dawson Creek’s water challenges are not unique in the drought-stressed Peace region.

In June, the community of Tumbler Ridge had to drain its community water supply to fight an aggressive apartment fire. Residents were then asked to restrict water usage for all non-essential activities, including washing machines and dishwashers.

“Tumbler Ridge is among numerous communities in northeastern B.C. that are under significant wildfire threat as the region enters its third year straight of significant drought conditions, which leave the area dry and extremely susceptible to fire,” Stand.earth added.

The jarring juxtaposition of an industry with a seemingly unquenchable thirst for water and a region beset by drought demands policy changes that would hopefully force the fracking industry to be more conservation oriented, Stand.earth says.

The organization said fracking companies pay extremely low rates for water withdrawn under provincially granted licences and permits.

The current charge to the industry, as set out in provincial regulations, is $2.25 for every million litres of water used.

“That means that the entire oil and gas sector will pay the Province of B.C. just over $20,000 for nine billion litres of freshwater they used in 2024,” Stand.earth said, adding that amount of money doesn’t even cover the costs of BCER staff to “administer and track” the water use permits and licences it issues.

The organization is calling on the provincial government to dramatically increase water rental rates to be on par with those of other provinces. “B.C. charges far less than other jurisdictions and of course we think that should change,” said Sven Biggs, Stand.earth’s Canadian oil and gas campaign director and, along with Kiki Wood, co-author of the report.

The Tyee asked the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship about Stand.earth’s call for a hike in water rental fees.

“We know more needs to be done to face the scale of the water challenges in B.C.,” the ministry replied.

“We have committed to new actions that were identified as priorities through public engagement, stakeholder discussions and the First Nations Water Table. This includes exploring all options to bolster the Watershed Security Fund, including increasing revenues to fund water priorities,” it added.

On the water conservation front, Stand.earth would like the government to “require the treatment and increased reuse of fracking wastewater,” which would help to lower the vast amounts of fresh water now being used in the fracking process.

Currently, the industry’s treatment of its toxic wastewater, which is laden with heavy metals, is highly saline and may contain normally occurring radioactive compounds as well, is essentially no treatment at all but holding it for reuse or pumping it underground for permanent disposal.

Water licence and permit changes needed?

The organization would also like to see all the authority to issue water licences and permits housed in the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship.

Currently, oil and gas companies get their long-term water licences and short-term water use permits from their own dedicated regulator, the BCER. This is the exception to the rule with all other water licensed to users in B.C. regulated by the ministry. Biggs told The Tyee that the droughts wreaking havoc in northeast B.C. underscore the need for strong, comprehensive provincial water leadership and that that is best achieved “by centralizing it with one body.”

Despite the oil and gas industry having its own dedicated regulator, Chapman noted that there have been times when the industry has been forced by the regulator to either drastically reduce or curb water takings.

When he was working as a hydrologist with the BC Oil and Gas Commission, Chapman notes, water licences were granted to two oil and gas companies, Ovintiv and Murphy Oil, allowing them to withdraw water from the Kiskatinaw.

The licences were issued with environmental flow needs very much in mind, Chapman told The Tyee.

In short, the licences had conditions embedded in them that dictated how much water the companies could withdraw based on water flows in the river.

“As droughts develop and river discharge drops, the volume of water that is authorized to be withdrawn also drops,” Chapman said. At some point, if they drop far enough, “all water withdrawals are suspended to ensure the protection of environmental flows.”

Chapman said that led to the fracking industry’s water withdrawals on the Kiskatinaw declining significantly in 2023 and being suspended altogether in 2024.

After leaving the commission, Chapman was asked as a consultant to assist members of the Blueberry River First Nations in negotiating new water management protocols in their territory, following a landmark decision in the B.C. Supreme Court that ruled the provincial government had violated the treaty rights of the nations by failing to consider the cumulative impacts that multiple industrial developments would have on their ability to hunt and fish and carry out other cultural practices.

The nations’ territory covers about 38,000 square kilometres in the upper Peace River region and is part of a vast area in northeast B.C. and neighbouring Alberta covered by Treaty 8.

In that work, Chapman said the Blueberry River First Nations, or BRFN, were guided by a desire to see rivers and creeks in their traditional territory managed with an eye to maintaining healthy water flows that would ensure that fish and other aquatic resources were protected.

Blueberry River First Nations members had “experienced significant and pervasive water shortages in rivers and streams and significant impacts on fish and aquatic resources as a result of excessive water diversions and withdrawals, principally associated with the burgeoning petroleum development across the treaty lands and withdrawal of very large volumes of water for fracking,” Chapman told The Tyee.

The Nations successfully pushed for a new water allocation process that would include strict and scientifically defensible limitations on what water could be withdrawn from what local streams and rivers based on the flows in those rivers. They secured the government’s agreement for the development of an online tool that would assist in those decisions.

But earlier this year, after paying for that tool to be developed and put online, the provincial Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship decided to take it off-line.

“In my view this is unfortunate,” Chapman said. “Not only is the BRFN Environmental Flow Needs Tool used to evaluate water licence applications, it is used by the public to help understand current conditions, and it is used by proponents to evaluate potential water withdrawal locations and scenarios, to help inform the application before they submit a water use application to government.”

In emailed responses to questions, the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship acknowledged that the water tool developed in conjunction with Blueberry River First Nations was no longer available online.

The ministry said in an email that since the province and Blueberry River First Nations reached agreement on “surface water commitments” in January 2023, no new industry applications to withdraw water in the nations’ territory had been received. “Because of this, the tool’s access has been paused until there are applications for surface water use that require its use.”

It went on to say that “the data and calculations” used to develop the tool “remain accessible to the parties.”

The Tyee reached out to Blueberry River First Nations for comment but received no reply.

[Top photo:Northeastern BC is experiencing drought in rivers such as the Kiskatinaw. Despite this, data shows the fracking industry is drawing more and more water every year. Photo by Don Hoffman.]