Articles Menu

National governments will meet in Montreal this month aiming to conclude a climate deal for the global aviation sector that would establish a cap-and-trade system for airlines that fly international routes and could cost as much as $12-billion (U.S.) by 2030.

At the upcoming triennial meeting of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), member states will be looking to approve the organization’s plan to cap greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for the industry’s international flights at 2020 levels and establish a carbon market in which airlines could buy offsets to meet their individual targets.

The Canadian government has endorsed the proposal from ICAO, a United Nations agency based in Montreal, and the United States and China issued a joint statement this month pledging to join the voluntary system and urging other nations to follow suit.

Canadian airlines say it is crucial to get a good international agreement because facing different regional climate rules would create major headaches. The European Union has threatened to impose carbon taxes on all flights landing at its airports if the international body cannot reach an acceptable alternative, a plan that prompted an angry backlash from the United States, China and other major competitors.

“We’re prepared to take a bit of pain if we can get some global consensus,” Air Canada’s director for environmental affairs, Teresa Ehman, said in an interview. “If it’s not a global solution, we’re going to fall into this patchwork [of regulatory approaches]. And if we fall into this patchwork, there will be all kinds of distortions and inequities in the market.”

The industry argues that a cap-and-trade system is far preferable to a carbon tax because airlines have limited ability to reduce fuel use, and hence GHG emissions, within their operations.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Environment Minister Catherine McKenna are due in New York next week for the opening of the United Nations General Assembly and climate-related meetings. In a UN agreement concluded in Paris – which Ottawa plans to ratify this fall – countries committed to limiting the increase in average global temperatures to less than 2 C above preindustrial levels. The deal left arrangements for international aviation up to the International Civil Aviation Organization.

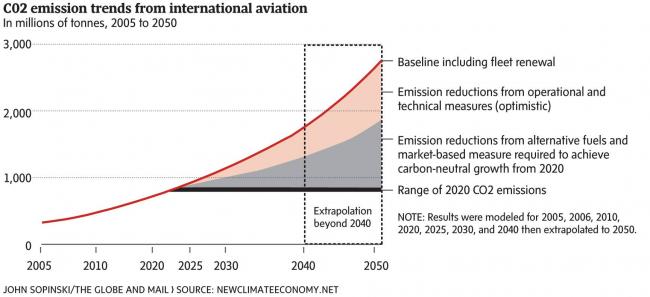

The sector is a major source of greenhouse gases, accounting for more than 2 per cent of emissions. If ranked as a country, aviation would stand ahead of Canada among top emitters. Based on strong growth projections, the sector’s share of global emissions is expected to grow to 10 per cent by 2050 unless dramatic action is taken.

The ICAO deal would cover only the emissions from cross-border flights, and would affect Air Canada, WestJet, Porter Airlines and AirTransat. The companies say it is too early to say what the cost would be, or how it would affect ticket prices or passenger volumes.

“We believe this agreement balances both the needs of the environment with the economic/growth benefits of aviation,” WestJet spokeswoman Lauren Stewart said in an e-mail. “However, any additional costs will have an impact on the consumer. The size of the impact is unknown and is only really a matter of speculation.”

The UN agency has provided a range of estimates for the yearly cost of the offset program. For 2030, as an example, it goes from a low of $2.9-billion (U.S.), to a midpoint of $4.3-billion, to a high of $12.4-billion, depending on the average price of offsets.

Those projections do not include the impact of any domestic carbon-pricing policies. The global aviation industry is forecast to earn $39.4-billion (U.S.) in profits this year on revenues of $709-billion.

After several years of debate, ICAO president Olumuyiwa Benard Aliu said he is optimistic the plan will be adopted at the Montreal meeting. However, the organization operates on the basis of consensus among its 191 member states.

“We are hoping to get that agreement and that would be the first for any sector globally,” the Nigerian aeronautic engineer said in a telephone interview. “We are looking forward to that with a lot of optimism and pride over the work we have put into it.”

One key issue is how many developing states join the voluntary deal in the early stages; airlines from countries that are participating in the agreement would not have to count emissions for routes on which they compete with those that are not. Dr. Aliu said he expects large developing nations to follow China’s lead.

Environmental groups support the ICAO’s cap-and-trade approach and efforts to improve standards for aircraft-engine fuel and implement more efficient air-traffic patterns, but say the agreement may not go far enough. “The commitment is already agreed – it’s the carbon neutral growth after 2020 – but it’s the participation that is the outstanding question right now,” said Annie Petsonk, a lawyer with the U.S-based group, Environmental Defense Fund.