Articles Menu

Apr. 27, 2023

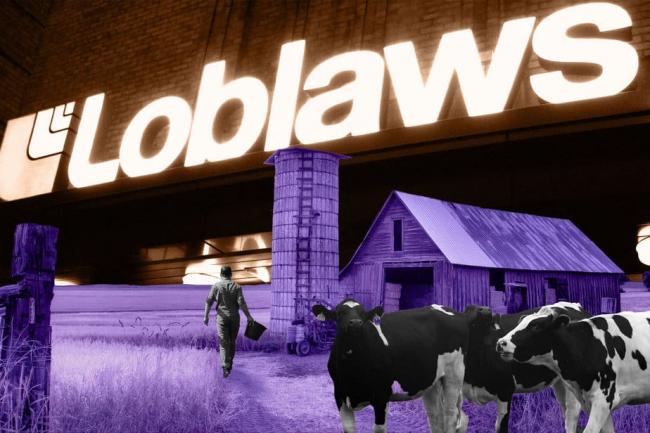

The real cause of skyrocketing food prices is corporate greed and market concentration—and one group of farmers has the receipts.

The National Farmers Union (NFU) has submitted data to the House of Commons agriculture committee which details how much retail food prices have risen compared to the prices that farmers receive for their goods. In fact, the union says retail prices have been completely “decoupled” from corresponding food inputs.

This means that while grocery store prices reach record highs, the farmers who stock their shelves are not seeing any of those profits—and a small group of processing and retail corporations are lining their own pockets instead.

“We need to be real about where the money is going,” NFU president Jenn Pfenning, who farms organic vegetables near Kitchener, Ont., told The Breach.

Retailers and processors are taking larger portions of the money spent on food, while farmers are stuck with rising costs and stalled prices.

“At the end of the day, retailers are posting record profits,” Pfenning said. “Farmers are, in many cases…posting either record or close-to-record losses and low margins.”

“From 2003-2016, bread prices rose steadily, far outpacing the minor increases in farmgate wheat prices,” NFU’s submission from last week explained. Farmgate prices are the prices of goods bought directly from farmers without markup added by retailers.

The union says the costs borne by consumers have been completely detached from the prices paid to farmers since the 2000s.

“Farmgate prices for wheat did increase in 2021 and 2022, potentially driven by the war in Ukraine and other factors. However, they did not come close to narrowing the gap that has steadily widened since the beginning of this data series.”

Another example about the costs of corn and corn flakes shows an even more dramatic example of the “decoupling” of retail prices from the prices of farmers’ goods.

The trend extends to other markets: the price of bacon has risen at a completely different rate than the price of hogs. At one point, the price of hogs actually fell while the price of bacon increased.

This massive disparity has been growing for decades. The trend suggests that it’s not the prices farmers are charging, the COVID-19 pandemic or the war in Ukraine driving the biggest rises in food prices. It’s the processors, packers and retailers who—in heavily concentrated markets—have the power to raise prices and take larger profit margins.

Supermarkets have doubled their profits since 2019, economist Jim Stanford of the Centre for Future Work reported in a separate submission to the agriculture committee.

Grocery executives have done this while blaming the pandemic, the war and their suppliers, as Sobeys CEO Michael Medline and Metro CEO Eric La Flèche did in their appearances before the committee.

But these companies have actually hiked their prices “above and beyond” what would be necessary to cover their increased costs, Stanford said. And big corporate processors like Cargill and PepsiCo have done the same thing.

“Like the supermarkets, food processors have also increased prices more than justified by their own increased costs,” Stanford’s report said. “Food manufacturing profits have grown notably since the pandemic: up 42% in the latest 12-month period, compared to 2019.”

Meanwhile, food banks say they’re at their “breaking point” as they try to feed more Canadians than ever before.

These corporations get away with it because they have high levels of control. Canada’s food retail and processing markets are heavily concentrated, which means a small number of companies control both the prices they pay to suppliers and the prices they charge consumers.

Five retailers—Loblaw, Sobeys, Metro, Costco and Walmart—control 75 per cent of Canada’s food retail market. In processing, the Canadian market is even more consolidated in some cases. Just two corporations—one of which was owned by Loblaw parent company George Weston Ltd. until recently—control 80 per cent of the bread-making market, for example.

The result is that farmers are facing dire financial circumstances, Pfenning said. They’re struggling with increased costs for virtually everything they need to grow food: land, equipment, soil amendments and more. Yet the prices they’re paid are virtually stagnant.

“Farmers and consumers are clearly in the same boat,” NFU vice president Stewart Wells said in a press release about the new data, “dealing with a highly consolidated processing and retail sector that can set prices to suit themselves and award enormous salaries to corporate CEOs.”