Articles Menu

Feb 10, 2017 - Earl Muldon sits at his kitchen table surrounded by family, sipping coffee. His wife Shirley brings over a plate of cream cake topped with huckleberries. They’re hand-picked from the land surrounding his two-storey home in Gitanmaax, a village of about 800 people from the Gitxsan Nation in northwestern British Columbia, near the town of New Hazelton.

To the Gitxsan people, 80-year-old Muldon is known by another name: Delgamuukw. That name — a symbolic ancestral chief name passed down from generation to generation of Gitxsan people — is also one of the most well-known chief names in the rest of Canada. Delgamuukw was the lead plaintiff in a historic court case that confirmed that Aboriginal title, ownership of traditional lands had not been extinguished by any colonial government.

“It’s a name that’s greatly respected. We’ve earned respect for it,” says Muldon, who was one of three people to hold the Delgamuukw name during the court proceedings.

The 1997 Supreme Court win against the B.C. government was important to indigenous people across Canada because it provided a new test to prove ownership over their traditional lands and waters. It was monumental to the Gitxsan because they seemed poised to assert self-governance over their 33,000-square-kilometre territory.

Fast-forward to the fall of 2016, when it emerged that Muldon was among a group of nine Gitxsan chiefs who had accepted money in exchange for their support of a controversial liquid natural gas (LNG) pipeline without consulting all of their nation’s members. Some Gitxsan people say that decision broke “ayook,” traditional Gitxsan law — and could undermine what the nation fought to prove in court 20 years ago.

So how did Muldon, who holds the hereditary name, Delgamuukw, that represented the unified Gitxsan Nation in their fight for their land, come to be among the group supporting resource development and spurring internal conflict among the Gitxsan?

The court case began in 1984. The Gitxsan and the neighbouring Wet’suwet’en Nation were frustrated because the B.C. government was allowing clear-cut logging to take place on their territory without hereditary chiefs’ permission. So, in an effort to get B.C. to address their claims to land rights, the chiefs of both nations claimed ownership and self-governance over their respective territories.

More than 100 Gitxsan chiefs, who each represent their own “wilp,” or house group, are responsible for upholding ayook and acting as the voice of their people in addressing cultural, environmental and economic issues that impact their territory. While he was just one of many, Delgamuukw became the named plaintiff for the case. His name represented the chiefs and, by extension, the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en people.

The chiefs spent the next several years giving testimony in court. They spoke in their own language, which was translated, describing ayook and “adaawk” (their oral history) in detail. To them, this oral testimony proved that the Gitxsan have occupied their territory under a complex legal system for thousands of years. But to Justice Allan McEachern, it was not enough to prove ownership of the land.

In 1991 at the B.C. Supreme Court, McEachern decided in favour of the B.C. government, describing aboriginal life as "nasty, brutish and short.” He announced that aboriginal title, the legal term for aboriginal ownership over land, had been extinguished by the Crown in 1858.

The Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en appealed, eventually taking their case all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. Twenty years ago this year, on Dec. 11, 1997, the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en saw the previous ruling overturned — and made history. The ruling had a huge influence on subsequent land rights cases, which have mostly favoured Indigenous plaintiffs.

“Delgamuukw wasn’t just for the Gitxsan. A lot of people have won their case on our case,” says Muldon.

The Delgamuukw decision set several important legal precedents that many other First Nations have built upon in the courts ever since. Firstly, the Supreme Court of Canada recognized that oral histories like the Gitxsan’s adaawk were as valid as written evidence. This means that First Nations across Canada can refer to their own oral history and laws when claiming their traditional land in court.

Secondly, overturning McEachern, the court case confirmed that Aboriginal title, ownership of land had never been extinguished in B.C. This is because, unlike in most provinces in Canada, B.C. didn’t negotiate historical treaties when settler populations moved into indigenous territories.

In short, the Gitxsan proved that traditional Gitxsan land is still Gitxsan land.

This draft of the Trustee Resolution of the Amdimxxw Trust, leaked in October 2016, shows the signatures of eight out of 10 Gitxsan wilp chiefs. Documents obtained by Discourse Media

In October 2016, two confidential documents were leaked on Facebook. They fuelled divisions over who can speak for the Gitxsan and how decisions are made on behalf of the Gitxsan people. These divisions have been growing gradually since the end of the Delgamuukw legal victory.

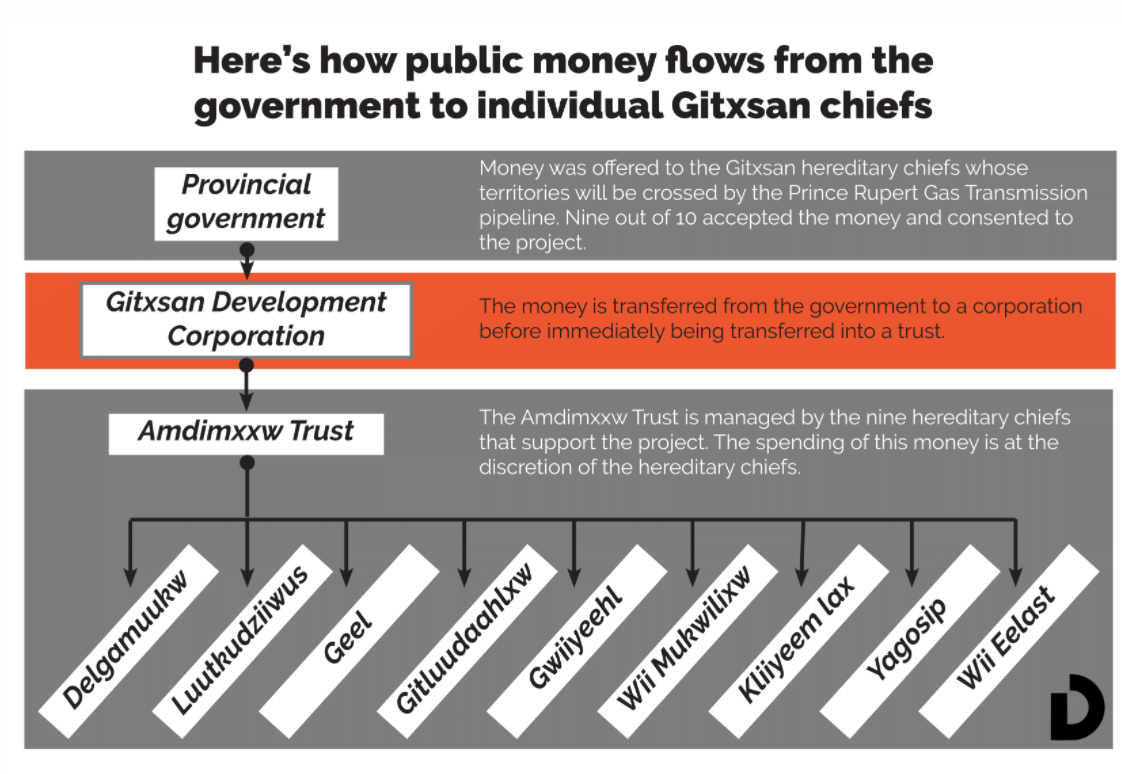

The documents showed that several Gitxsan hereditary chiefs, including Muldon, gave consent on behalf of the Gitxsan Nation for TransCanada’s proposed Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Project (PRGT). The 900-kilometre pipeline would carry LNG from northeastern B.C. to the Pacific NorthWest LNG export terminal proposed for Lelu Island on the province's north coast, crossing the territories of 10 Gitxsan wilp groups along the way.

The signatures of eight out of these 10 wilp chiefs appeared on a document called “Trustee Resolution of the Amdimxxw Trust,” dated Sept. 6, 2016. This document lists the chief names next to dollar amounts, dividing a total of more than $5.3 million between them. After this document was leaked, the chiefs released an information package to members, confirming that nine of the 10 wilp chiefs whose territories would be crossed by the pipeline had given their consent to the project.

The second document leaked was called the “Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Project Natural Gas Benefits Agreement.” It says the B.C. government will provide the Gitxsan Nation with numerous payments, adding up to nearly $6 million, at various stages of construction in exchange for support of the project. It contains a clause that prohibits any Gitxsan member from challenging the LNG pipeline project in court.

When asked about the agreement, a representative who asked that the statement be attributed to the government of B.C. wrote in an email that “financial benefits provided through the agreement are transferred to the Gitxsan Development Corporation on behalf of the Gitxsan Nation. Benefit payments are not made to individuals.”

Payments from the government are made to the Gitxsan Development Corporation (GDC). GDC director Rick Connors confirmed that he facilitated payments from the province on behalf of the chiefs. Connors said that upon receiving the payments made thus far, he immediately transferred the same amount into the Amdimxxw Trust. Connors called the Amdimxxw Trust the “vehicle through which the directly impacted hereditary chiefs will manage their trust funds.”

Connors stressed that the agreements leaked were draft agreements. The benefits agreement with the province is now finalized and public, and Connors confirmed the Gitxsan have received $1.2 million from that agreement so far. The Gitxsan have also reached a separate project agreement with PRGT. While the financial details are confidential, Connors said the funds from that agreement also went into the Amdimxxw Trust.

The total value of the Amdimxxw Trust and how much is currently in the name of each chief also remains confidential. When asked if the $5.3 million in the draft agreement is correct, Connors said, “I’m not at liberty to neither confirm nor deny that.” He did say that the chiefs are looking to spend some of the money on projects that would benefit the broader community, such as an elders’ home or a low-cost housing facility.

If the draft agreement of the Amdimxxw Trust is correct, Muldon’s share of the pie comes in two instalments: one of $40,000 and a second of nearly $300,000.

“There’s such a massive amount of money. It’s bribery, more or less,” Muldon admits. But he doesn’t consider the money his to spend. He says he will discuss with his wilp members how the money could best serve the community. Until then, it will remain in the Amdimxxw Trust.

“I had members phone me and say they want $10,000, they want $20,000 — kind of a blackmail type thing. We never spent any money. We didn’t want to deal with that type of method,” Muldon says. “It’s just sitting in the pot, that’s all.”

In addition to speaking with Muldon and Gordon Sebastian, another chief whose signature appeared on the “Trustee Resolution of the Amdimxxw Trust,” Discourse Media attempted to contact the six other chiefs whose signatures appeared on the resolution, as well as the ninth chief whose support was later confirmed. They were unavailable or unwilling to comment about why they consented to the project.

When asked how they consulted with the Gitxsan on the project, a representative from PRGT wrote in an email, "TransCanada has a robust engagement policy that guides all of our interactions with Indigenous communities. As a result of those interactions, PRGT has been able to sign benefits agreements with 13 First Nations along the route. This demonstrates that our approach works."

Muldon’s nephew was upset when he first heard the news that his uncle had signed on to the pipeline deal.

“My initial reaction was disappointment,” says Kirby Muldoe, who works for SkeenaWild Conservation Trust, which opposes siting the pipeline terminus on Lelu Island. “And not just on the part of my uncle, but on the part of all who signed. I felt the Gitxsan people were not consulted as we should be. In both our laws and western laws you have to be consulted. And none of that happened.”

But Sebastian says the chiefs went through an extensive four-year process before coming to a decision. This involved over 45 meetings with PRGT, the provincial government, industry experts and those who are opposed to the project. Sebastian is also executive director of the Gitxsan Treaty Society (GTS), which takes on projects working toward self-governance on behalf of the Gitxsan Nation.

“So what we did over four years is we evaluated everything. The environment. The birds. The animals. I did all that stuff. I took it all into consideration. Me as well as the other 10 chiefs. Nine out of 10. We did all that and we did it jointly,” Sebastian says.

“Consultation has happened. We did it from the point of view of our ayook. And we felt we did a very good job.”

Muldon was unaware that his consent for the project would be represented as standing in for that of the entire Gitxsan Nation. He claims he did consult with some members of his wilp before making the decision. “We had discussions on it and then I had discussions with my family. We decided we have to go with progress.”

But according to Neil John Sterritt, a Gitxsan member and a consultant who assists First Nations with aboriginal rights and title research and asserting self-governance, the chiefs did not follow ayook.

Sterritt was a witness in the Delgamuukw court case and was on the stand for more than 30 days. He fears the chiefs who signed the agreements have undermined key legal principles that came out of their victory. In Delgamuukw, the courts said that "Aboriginal title is held communally." This means that the land belongs to the Gitxsan Nation as a whole and not just to hereditary leaders. Therefore, decisions regarding the land have to be made communally.

“No individual hereditary chief can make such a decision because the Gitxsan Nation is a collective of all members,” Sterritt says. “And the hereditary chiefs act for all members and they should all be involved in any decision that binds the nation, which this does.”

Sterritt says that under ayook, which was described in the court case, Gitxsan chiefs must consult with all members of their respective wilp groups before making a decision that would impact them.

“When we did Delgamuukw, I went to meeting after meeting with each house. They had a chance to ask questions. We told them what the implications were if we won or lost. If they agreed, they would tell the hereditary chief and the hereditary chief would then be able to sign documents on their behalf.”

“I’m not saying exactly that has to happen, but something mirroring that has to happen. In other words, there has to be due diligence and due process, and there’s been no due diligence or due process in this,” Sterritt says.

“It was done secretly,” he adds. “It was done so people like me would not know. Not just me, but a lot of people who were opposed to the way things operate.”

This is not the first time divisions over a pipeline agreement have caused controversy among the Gitxsan. In December 2011, Enbridge announced it had reached a deal with the Gitxsan in support of the now-dead Northern Gateway pipeline proposal. That deal had been signed by former GTS chief negotiator Elmer Derrick, who faced similar backlash for negotiating behind closed doors.

A few days after the December announcement, a blockade of the GTS office formed, under the direction of a number of hereditary chiefs. The GTS then claimed it also represented the hereditary chiefs and filed an injunction against the blockade. The two sides ended up in court, where they repeatedly fought over who has the legal right to speak for the Gitxsan Nation.

Around the same time, an assessment for a forensic audit of the GTS was conducted after several allegations of misuse of funds were reported to the police against Derrick, former negotiator Bev Clifton Percival and current executive director Sebastian. None of the allegations were ever proven.

Despite being among those who signed on to support the latest LNG pipeline, Muldon himself acknowledges that there are problems with how the Gitxsan govern themselves. He is frustrated with how the GTS and the GDC operate.

“We have to clean house,” says Muldon, adding that he feels he’s not being listened to. “What’s going on is not good. We’re not further ahead when we abide by some dictator. Policies that our people are doing down at the office are not totally our wishes. But they have the say in the office. That’s basically what it is.”

“It’s almost spineless to see what our people working for us are doing,” he says.

At the same time, Muldon is not opposed to development on the territory. He wants jobs for the Gitxsan people. He is open to the PRGT crossing Gitxsan land. However, he remains opposed to the proposed location of the Pacific NorthWest LNG terminal on Lelu Island, a common concern from First Nations and environmentalists.

Twenty years ago, the Gitxsan defeated the B.C. government in court by being united. But now, internal division has become rife among Gitxsan chiefs and members. A chasm has formed in the nation because chiefs disagree over how best to implement the Delgamuukw decision.

It’s important to note that even though the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en won their case, the courts still did not declare that they have Aboriginal title. The judge determined they would have to go back to court separately and seek a declaration of title. And while the Tsilhqot’in Nation did just that in 2014 by building on the legacy of Delgamuukw, the Gitxsan have not.

“It’s something that we should be doing instead of the chicken shit politics that we do here,” says Muldon.

When asked what holding such a historic and prominent name like “Delgamuukw” means to him, the elderly Muldon took the question literally. “Delgamuukw is the sunset, the red glow on the horizon when the sun starts to set,” he says.

Twenty years after the sun set on their landmark legal victory, the Gitxsan are divided over decisions Muldon and the other chiefs made. While the province and industry claim they have support from the Gitxsan for the pipeline plans based on the signatures of some Gitxsan hereditary chiefs, the issue within the Gitxsan Nation remains unsettled.

Photo above: Gitanmaax is a reserve in northern B.C. where Gitxsan members discovered confidential documents revealing that some hereditary chiefs had given their consent for the PRGT pipeline in exchange for money. Photo by Trevor Jang, Discourse Media