Articles Menu

June 5, 2020

Reading Time: 12 minutes

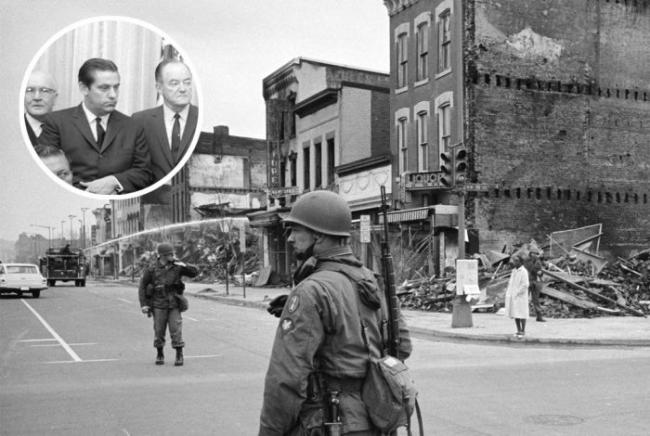

Today we’re facing the exact same questions that Americans were asking just over fifty years ago, in 1967 and 1968, as riots took place all across America, resulting in over 70 dead and untold injured.

In order to understand how civil unrest had reached such proportions, and how to prevent it from occurring in the future, President Lyndon B. Johnson established the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders — known as the Kerner Commission, after its chairman, Otto Kerner Jr., who was governor of Illinois at the time.

After a year of work, the commission reached conclusions that belied expectations, among them: America was divided into “two nations, one black, and one white,” and institutional anti-black racism was ultimately responsible for the riots.

It has been said that “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” When it does, it’s a privilege to have the wisdom of those who have “seen it all before,” since their perspective can help us understand the chaotic events of today through the long lens of history.

In this week’s WhoWhatWhy podcast we talk with Fred Harris, the only living former member of the Kerner Commission.

The oldest living former US senator, Harris served two terms representing the state of Oklahoma, was chairman of the Democratic National Committee following the tumultuous 1968 Chicago convention, and twice sought the Democratic nomination for President. He is now a professor emeritus at the University of New Mexico.

Harris offers no quick fixes to what ails us, though he does outline the proposals advanced by the 1968 commission — many of which bear an uncanny relevance to today’s turmoil.

There is something both comforting and enraging about strapping ourselves into a time machine for a 23-minute journey back to 1968. We get a glimpse at how the country survived, what, if anything, we’ve learned, and what history tells us about our own future.

Listen to podcast at link.

Full Text Transcript:

As a service to our readers, we provide transcripts with our podcasts. We try to ensure that these transcripts do not include errors. However, due to time constraints, we are not always able to proofread them as closely as we would like. Should you spot any errors, we’d be grateful if you would notify us.

| Jeff Schechtman: | Welcome to the WhoWhatWhy podcast. I’m your host, Jeff Schechtman. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson created what came to be called the Kerner Commission. Chaired by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, its goal was to identify the causes of the violent 1967 riots that killed 43 in Detroit and 26 in Newark while causing mass casualties in 23 other cities. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | Then, as now, there was pent-up frustration, which boiled over, particularly in many poor black neighborhoods setting off riots that rampaged out of control. At the time, many Americans blamed the riots on what they saw as misplaced black rage and often vague outside agitators. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | But in March 1968, the Kerner Commission Report turned those assumptions on their head. It declared that white racism, not black anger, was at the root of American turmoil. It talked about bad policing practices, a flawed justice system, unscrupulous consumer credit practices, poor or inadequate housing, high unemployment, voter suppression and other culturally embedded forms of racial discrimination that all combined to ignite the fuse on the streets of African American neighborhoods. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | “White society,” the presidentially-appointed panel reported, “is deeply implicated in the creation of the ghetto.” “The nation,” the Kerner Commission warned, “was so divided that the United States was poised to fracture into two radically unequal societies, one black and one white.” |

| Jeff Schechtman: | Today, there is only one living member of that commission, and he also happens to be the oldest living current or former United States senator. He was once a candidate for president to the United States. He served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee. He served for two terms as a senator from Oklahoma. And it is my pleasure to welcome, Senator Fred Harris to the WhoWhatWhy podcast. Senator, thanks so much for joining us. |

| Fred Harris: | You bet. Thank you. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | Talk a little bit about the state of the country as you remember it back in 1967. |

| Fred Harris: | Well, it was, as the Kerner Commission said, the country was becoming two societies, one black, one white, separate and unequal. President Johnson when he appointed us [inaudible] my suggestion that he said, “Let your search be free and tell the truth. Find the truth and tell it.” Well, we did. |

| Fred Harris: | And what we said was that racism and poverty were at the base of the terrible disorders and very strong protests that erupted all over the country back then after the hot summer of 1967. And we recommended, as you said, strong and immediate action to do something about the terrible inequities, social, political, and economic that existed in our country. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | And as you look out today, 52 years later, at what has transpired and seeing so many of those same issues playing out today, talk a little bit about your perspective on that. |

| Fred Harris: | Well, I’m, as you know, the surviving member of the commission. I’m getting a lot of call now and people saying, “How do you feel about what’s going on and about the killing of George Floyd and others, and the terrible inequality of wealth and income, the worsening of segregation and discrimination in the country?” Well, the way I feel is like most American now feel, which is sick at heart, grief stricken, mad as hell. |

| Fred Harris: | And I would say, but there are some differences now with these protests that are occurring in the country from what happened back in 1967 and ’68. It’s larger. These protests are much larger. They’re more widespread. They’re multiracial now. They’re longer lasting. And they are cutting across race and class. And I think that we’ve developed in recent years a huge leadership cadre of people of color. They’re demanding to be heard and we have to listen and act. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | When you look back at the recommendations of the commission, many of those recommendations, many of the conclusions that you reached in that report didn’t sit well with President Johnson. Talk about that. |

| Fred Harris: | Well, Johnson was misinformed about what was in the report and he was, of course distracted by the terrible involvement of the United States in war in Vietnam. And he rejected our report, which is especially sad because President Johnson did more against racism and poverty than any president before or since. Despite that, we’ve made great progress on virtually every aspect of race and poverty for about 10 years following the Kerner Report. And then that progress stopped and was reversed, and that regression goes on now still. |

| Fred Harris: | Back then, for example, we were reducing poverty, the rate of poverty in the country. For example, the black/white gap in education was being reduced at a rate that had it continued, there would be no such gap today. That’s what makes people like me particularly sad and angry to see all of that wasted time and these wasted lives. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | And what was it that really had an influence, that had an impact after the report came out? As you say, Johnson didn’t really buy into it. He rejected the report. What drove the changes at that point? |

| Fred Harris: | Well, there was just a feeling generally in the country and a majority of the Democrats in the Congress in favor of civil rights and of the anti-poverty programs and so forth. And that carried over for a while. But, starting with Nixon and then especially with Reagan, the emphasis switched more and more to law and order. |

| Fred Harris: | And today, there is less violence, I think, than there was back then associated with these protests. It’s still too much, and is by people who are not really, don’t have the same agenda, who have their own agenda, but that shouldn’t be the focus. It shouldn’t have been the focus then of the consideration of race and poverty and it shouldn’t be now. We don’t need to militarize this problem. To coin a new word, we need to communitize. People need to stay mad as hell, at least until November, to change our government. |

| Fred Harris: | But, the federal government has to take the lead, but it can’t be all. What we need, a civil society to be involved. And every community ought to have a local organization, a group set up, not to study the problem. We’ve studied the problems to death. We know what needs to be done and we need to begin to act locally and then federally when we can on schools, on housing, on infrastructure, on jobs and income, on racism, health. |

| Fred Harris: | I think we ought to say, these people like George Floyd and others, the hundreds, the hundred and thousand people who’ve died from coronavirus, that they should not have died in vain. And we ought to take responsibility for changing things and in a big way, and say to our politicians, “Go big or go home.” |

| Jeff Schechtman: | What were some of the specific recommendations that the Kerner Report made that may not have been implemented at the time, but some of the recommendations that you would have liked to have seen implemented then? |

| Fred Harris: | Well, for example, in regard to the police, we, they were implemented. The police and the National Guard, of course, had no training in crowd control or disorders or whatever. And most of the people that got killed and during those disorders were black and most of them were innocent. And so we said, we ought not to militarized the police. We ought to make the police look like and to be a part of the communities, which they’re supposed to protect and serve. And we ought to change the culture of the police. |

| Fred Harris: | In too many places, they were coming, they were white and coming in from the outside during the day, really enforcing the law as they saw it against the black community rather than being a part of that community. So for a while, we had community policing. We began to do a lot of that, but most of it have been abandoned now. For a while, we had the, and fairly lately, during the Obama Administration, for example, we had the Department of Justice sort of taking over the local police departments, which were using force too much as a first effort to deal with local problems. And all of that now has been abandoned. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | One of the things that was striking in reading so much of the dialogue from that period was this idea that somehow it was all being caused by outside agitators. We’re hearing some of that rhetoric again today. Talk a little about that, Senator. |

| Fred Harris: | Yes. Two things occurred to me about that. One is, I think there was a lot of white people in the country who thought, “Well, it’s those mean old Southerners that really is the problem here.” But just as we saw in Minnesota, and as back in the Kerner Commission days, we saw it in places like Cincinnati and Cleveland and Milwaukee and elsewhere, that racism was not just a problem in the South. It was endemic to the whole country, and with the intertwined problems of race and poverty. |

| Fred Harris: | These were national problems. And they were not just a situation where one white person that hates black people. It was, racism is endemic, and so was poverty in this country. And it’s a national problem. We’ve got to deal with it nationally, but we also ought to, right this minute, begin to deal with it face-to-face at the community level. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | Talk a little bit about how the commission talked about these issues at the time. When the commission had its meetings, talk a little bit about what the dialogue was like with respect to these issues of race and poverty and the way they had become so systemic in the country. |

| Fred Harris: | Well, first of all, what we did was we held 20 something days of hearings where we heard from a great group of people, I think 40 something witnesses ranging from J. Edgar Hoover to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Then we authorized a great many studies by experts of these steady problems and of racism and poverty. |

| Fred Harris: | We sent out teams of experts to all of the riot cities. And then we divided into teams. John Lindsay and I, the mayor of New York, were a team for traveling around the country to these cities where the disorders had occurred. And we continue to team to lead the writing of the report. And we read aloud every single word, and voted on every single word of that commission report. We had come back, each of us, really sobered and shaken by what we’d seen out in the country and at the hostility, which people quite understandably felt toward the police. We saw, ourselves the awful conditions of racism and poverty, which existed in the black sections of the country. |

| Fred Harris: | We made a mistake, I think, in the Kerner Commission in not taking the public along with us the best we could, the media, particularly. Our hearings were closed. And when John Lindsay and I, for example, went out to Milwaukee and Cincinnati and so forth and walked the streets and talked to people and saw the depths of their desperation and anger, it’s a shame that the people couldn’t have seen those things themselves. |

| Fred Harris: | That’s also different now. People have seen it. They saw that policeman’s knee on the neck of George Floyd, and they heard him say that he was dying and calling his mother’s name. You couldn’t look away. We can’t look away. And that, I hope, will lead us to action this time for sure. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | The report was finished in March of 1968. It was in April of ’68, a month later, that Martin Luther King was assassinated, and five months later that Bobby Kennedy was. Talk a little bit about as someone who had looked at these issues as part of the commission, how you felt about all of this in light of what transpired shortly after the report was finished. |

| Fred Harris: | Of course, it was the worst year of my life, 1968. And Robert Kennedy, for example, was a seatmate of mine in the Senate, and we were each other’s closest friend in the Senate. But, we had that awful Democratic Convention in Chicago that year. We had the Vietnam War worsening. The country was just really falling apart. It is amazing that we got by as well as we did. I think that this is another chance, maybe the last chance, we have to really deal with these problems on the local level and at the federal level in a way which will really eliminate racism or the harsh results of racism and poverty. And we have the means to do it. |

| Fred Harris: | We had a chance at the writing of the Constitution to do it, again, at the end of the Great Depression. And we made some headway, well, a lot of headway in regard to poverty and inequality of income and wealth. We had another chance at, in 1968. And I hope that this time, we’re going to respect the idea that these dead, including the 100,000 plus people who’ve died from the coronavirus, these dead shall not have died in vain. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | What gives you optimism? Having seen what happened in 1967, not 1968, having seen that up close and seeing how little we’ve come today, what gives you optimism? |

| Fred Harris: | First of all, we’ve got, as I said, a huge leadership cadre of people of color now. It’s far greater than we had then. And that’s a great asset. |

| Fred Harris: | Secondly, people are really aware. You cannot not be aware of these endemic problems of race and poverty. And a great majority of people are willing to do the things, want to do, the things that must be done. There is greater activism today than I’ve ever seen in my lifetime. And as I said, people are mad as hell. I want them to stay mad through November to change our government. But not wait until November, start now at the community level to do what must be done. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | How do you compare what you witnessed in 1968 to what you’re witnessing in 2020? |

| Fred Harris: | There is a comparison. These protests are larger. They’re more widespread. They’re more multiracial. They’re longer lasting. They cut across race and class lines. And I think the way people feel can’t be quelled by some kind of militaristic approach. They’re not going to stand for that. And the only thing that’s going to bring us peace and a stable society of self esteem is justice and the elimination of the inequities, political, social, economic that exists in this country. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | And finally, do you think that the words of the Kerner Commission Report that we are two nations, one black, one white, are still true today? |

| Fred Harris: | More true than was true even then. We began to desegregate. We passed open housing laws. But then, now we’ve regressed in the cities. The housing, the schools are re-segregating. And there is far more anti-black violence than was true before. Unemployment among black people has continued to be about twice what it is for the rest of our society. And the COVID death disparity is so stark [Inaudible] far greater proportion of black, Hispanic, indigenous, poor people are dying from the coronavirus than is their proportion in this society. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | Former US senator, former member of the Kerner Commission, Fred Harris, I thank you so much for spending time with us here on the WhoWhatWhy podcast. |

| Fred Harris: | You bet. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | Thank you. And thank you for listening and for joining us here on Radio WhoWhatWhy. I hope you join us next week for another Radio WhoWhatWhy podcast. I’m Jeff Schechtman. |

| Jeff Schechtman: | If you liked this podcast, please feel free to share and help others find it by rating and reviewing it on iTunes. You can also support this podcast and all the work we do by going to whowhatwhy.org/donate. |

Related front page panorama photo credit: Adapted by WhoWhatWhy from GoToVan / Flickr (CC BY 2.0).