Articles Menu

Aug. 23, 2024

“I sure hope it doesn’t come to it, but we are prepared.”

That summarized the messages from more than 20 speakers opposing the proposed Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline at a community town hall in Kispiox, B.C., last month.

The “it” they were talking about was the prospect of a major confrontation with British Columbia and Canada over the construction of the pipeline and what a young Wet’suwet’en woman called “pipeline by gunpoint.”

The racism, violence and trauma, and intra-community rifts faced by the Wet’suwet’en during the construction of Coastal GasLink were a constant presence in the discussion.

That’s why Kolin Sutherland-Wilson, elected Chief of the Kispiox Band and the lead organizer of the event, bookended it with a focus on what he called “solutions,” pathways for the community over the coming months that might stop it from leading to blockades, conflict and the kinds of violence associated with the RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory.

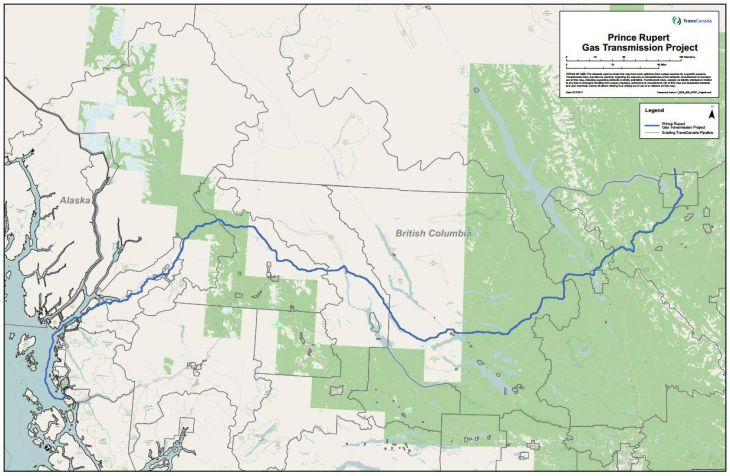

The pipeline was first approved in 2014, intended to supply natural gas to a proposed LNG export facility on Lelu Island near Prince Rupert. That project received an environmental assessment certificate in 2014 but was subsequently abandoned after facing strong opposition from First Nations, including Tsimshian nations near the export facility, Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan leaders and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs.

But on June 21, TC Energy, at the time the owner of Prince Rupert Gas Transmission, submitted a route amendment application that would move the pipeline’s downstream terminus from Lelu Island to the proposed $55-billion Ksi Lisims LNG project near the Nass River estuary, inside the Nisga’a Nation Treaty Lands.

That application is still going through a public engagement process and is opposed by the Lax Kw’alaams First Nation, who maintain the project will impact their territory. It is also opposed by numerous environmental groups. The environmental assessment certificate application for the Ksi Lisims LNG terminal also remains in review.

In spite of this, TC Energy submitted a start-work notice for the line to the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office on May 24.

It said the Nisga’a Lisims Government and Western LNG, which have since purchased the pipeline from TC Energy, would begin construction this Saturday.

Sutherland-Wilson and other speakers focused on the fact that a major pipeline project with a pending route amendment and no approved terminus is being allowed to start construction. They argued — in a sentiment shared later by Nathan Cullen, the BC NDP MLA for the region — that the route changes and the project’s new terminus indicate that this is not the same pipeline that was approved in 2014 and it should be assessed as a new project.

The other point speakers emphasized — similarly focused on the demand for an immediate halt to construction and the initiation of a new assessment — is that many things have changed in the last 10 years.

The province has a new, substantively different Environmental Assessment Act. It passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, or DRIPA, in 2019. And a number of legal decisions have challenged the province’s frameworks for assessing the cumulative effects of industrial development.

The impacts and science of climate change, too, have become much clearer with regards to both the question of building new fossil fuel infrastructure and warming’s escalating impacts on the Skeena watershed, its ecosystems and its people.

Ardythe Wilson, who holds the name Dimdiigibuu in Wilp Gutginuxw and who was involved in the 1997 Delgamuukw case, speaking directly at Cullen, put the question of the role of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in blunt terms.

“It remains to be seen whether it’s all bullshit or not.” She asked whether it is “just an empty instrument that means nothing.”

Environmental assessment certificates expire every five years. The Prince Rupert Gas Transmission line received a five-year extension on its certificate in 2019, two years after the Pacific NorthWest LNG project at Lelu Island was cancelled and two years before the Ksi Lisims LNG project was announced.

TC Energy, at the time known as TransCanada, requested the extension based on its acknowledgment that the Pacific NorthWest LNG project left it with no export terminals available for the pipeline.

The Environmental Assessment Office extended the certificate because “an approval of the extension request would not constitute a material change with consequences to Indigenous groups’ exercise of their Aboriginal interests and treaty rights that has not otherwise been considered and appropriately addressed during the original EA.”

“The Crown’s duty to consult and appropriately accommodate potential impacts of the proposed extension on Aboriginal rights and title have been adequately fulfilled,” it said.

Prince Rupert Gas Transmission’s current EAO certificate expires on Nov. 25.

The company will need to show the project has been “substantially started” by then, or it will be forced to undergo another environmental assessment process under the new act.

If the EAO rules the project has been substantially started, its permit will be extended in perpetuity.

Some Chiefs of Gitxsan Wilps signed impact benefit agreements in 2014, but speakers at the town hall questioned the tactics used to obtain those signatures and argued that, given the changed project and circumstances, those agreements do not count as consent or even consultation, particularly not within the context of DRIPA.

Wilson described these signatures as an example of how the province “plays on the dynamics of our house groups” to facilitate the demands of industry and explained that Gitxsan governance is defined by “decision-making by consensus,” which, in her view, renders documents signed by individual leaders illegitimate.

These agreements have been kept secret. As Sutherland-Wilson noted, “There’s not much I can say about the agreement directly with PRGT, because, quite frankly, I think none of us have seen that.” An analogous agreement related to Coastal GasLink, written in 2016, was made public in 2020. It required the signatory band, under threat of financial punishment, to silence dissenting members. Wilson, referring to this tactic, asked, “What the hell kind of agreement is that where you have to oppress your own people?”

Of the roughly 150 people at this event, the 25 who spoke were consistent in their message of grim resolve: nobody wants a messy and traumatizing fight, but as one older Gitxsan man put it, speaking of the land and water of Gitxsan Laxyip, “We’re gonna lose this all when this pipeline goes through.”

The next months are crucial for the future of this pipeline. The B.C. government could require the project to go through a new assessment process.

Cullen, who took the mic to speak at the end of the night, well past 11 p.m., outlined some of the reasons this would be justified.

The project permit was “granted under an entirely different Environmental Assessment Act,” he said.

“The second thing that has changed since then, is that we now have a law, DRIPA... which is an enabling law that allows the government, and informs the government, instructs the government, to change other laws.”

“The other thing that’s changed about this permit from 10 years ago is the fact I would say that there’s new ownership of this pipeline, there’s a new destination of this pipeline, and there’s broadly, as best as we can tell, not entirely... a new route in many places of this project.”

“So the question that the proponents have to answer is, is this the same project that you were permitted for back in 2014? Should it not be better that it receive a new permit under environmental assessment laws that are current, that are DRIPA compliant and that inform consultations?”

The province could refuse to grant the project “substantially started” status once its certificate expires in November and require it to apply again under today’s rules. The ball is in its court.

But many people at the town hall made it clear: they are prepared to act if the province won’t.

Nick Gottlieb is a writer and a graduate student at Simon Fraser University, as well as the author of Sacred Headwaters.

[Top photo: Some opponents warn the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline will face protests similar to those that led to confrontations on the Coastal GasLink pipeline route. Photo by Amanda Follett Hosgood.]