Articles Menu

Oct. 4, 2021

When Sally Hope was a teenager, summer was the season of salmon. Every year, she would spend weeks at her grandparents' fishing camp on a remote reach of B.C.'s Fraser River catching and air-drying fish to feed the family through winter.

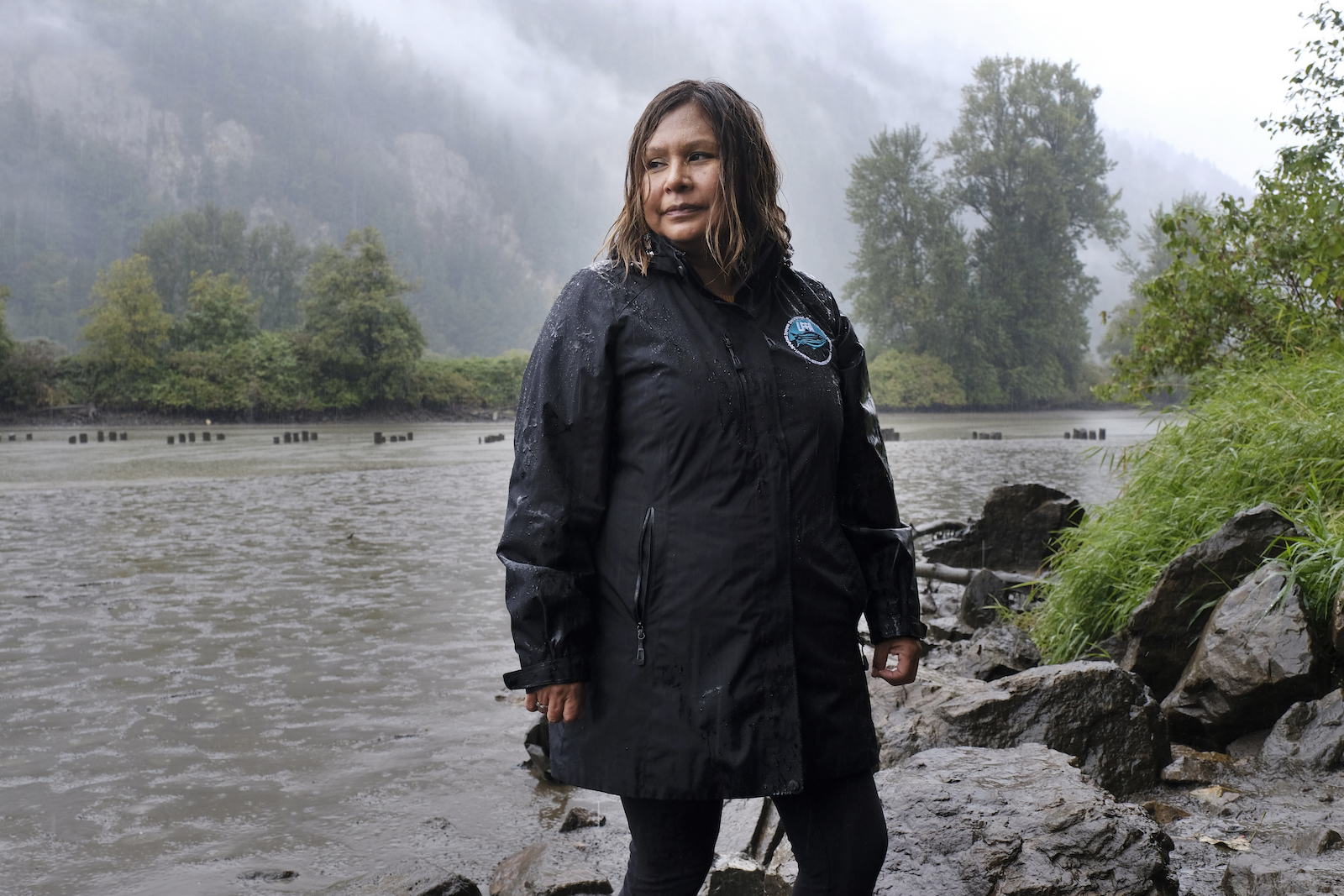

Standing under an autumn downpour on the banks of a Fraser River tributary near Abbotsford, B.C., the lands and resources manager for the Shxw'ōwhámel First Nation's eyes still light up at the memory of summers past.

“We wouldn't leave the camp, everything was there that we needed. There was so much exploring to do, and we also had work. We were taught how to do laundry, peel potatoes. We had jobs very young,” she said. “Those memories are what keeps me going.”

Still, her joy is fleeting: In recent years, she has been lucky to get a single fish.

Air-drying salmon during the summer is vital for many First Nations along the Fraser River, Hope explained. The practice provides culturally important food and teaches valuable lessons. Yet the decline of the salmon is putting this “dry-rack” fishery in peril, with the few FSC openings often occurring too late in the year. Photos: Portrait by Jen Osborne / Canada's National Observer. Drying salmon provided by Eden Toth / Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance

Salmon stocks on the Fraser have tumbled in the past decade, leading Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) to severely limit harvesting on the river, including Indigenous food fisheries.

Under Canadian law, DFO is responsible for managing all of Canada's oceans, marine fisheries (any fisheries that touch saltwater, including anadromous fish like salmon), and communities that depend on the fish. First Nations have a constitutional right to harvest fish for food, social, and ceremonial (FSC) purposes. That means that unlike a typical commercial or recreational fishing licence — a privilege DFO grants to harvesters — after conservation, the department must give First Nations fisheries for FSC purposes priority access to fish.

While DFO has allowed some FSC chinook salmon fishing this year, the openings are short — many are only a few hours long — and are scattered throughout the season. In September, DFO allowed some commercial fisheries for more plentiful pink salmon in coastal waters near the Fraser, despite criticism from environmental groups and First Nations over the potential impact on all salmon species migrating up the river, including scarce sockeye and chinook.

You don't play with fish. You don't play with food.

Murray Ned, executive director of the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance

The department has also allowed limited recreational fishing for some salmon species on parts of the Fraser River and a few of its tributaries, even as Indigenous food fisheries along the river remain curtailed. It's a frustration for Hope and other Indigenous people who believe the practice breaks important traditional laws, particularly with so few fish in the river.

“You don't play with fish. You don't play with food. That's where there's challenges seeing recreational fishers,” added Murray Ned, executive director of the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance, a coalition of 23 First Nations working to manage and restore their fisheries, who joined Hope by the river on this rainy day. While he has sympathy for sport fishers, many of whom he knows care for the fish and the river, their relationship to the salmon is incomparable to the deep ties between First Nations and salmon.

Ned is from the Sumas First Nation and like Hope, he has seen the annual FSC harvest dwindle in recent years. It's a devastating blow that could easily get worse.

“If we go to a place where we don't have any fish, we lose our complete cultural identity,” he said.

However, there is one thing upon which both anglers and First Nations agree: DFO is failing the salmon and the people who love and depend on them.

Recent years have been rough for most B.C. salmon fisheries, with the number of salmon returning to the province hitting historic lows in 2020, especially some stocks on the Fraser River.

In 2020, only 193,000 sockeye returned to spawn, the lowest number since records began. Of the 28 chinook salmon populations in southern B.C., nearly half are endangered, threatened, or at risk, according to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). While other salmon species are in better shape, the situation remains precarious.

In the face of the crisis, then federal fisheries minister Bernadette Jordan in June announced long-term closures on roughly 60 per cent of B.C.'s commercial salmon fisheries, including several that could impact Fraser River salmon migrating upriver to spawn. Recreational and FSC fisheries on the Fraser are also severely constrained.

Only 193 000 sockeye salmon returned to spawn in the Fraser River last year — by far the lowest number since records began. Other salmon runs across B.C. have also declined in recent years, prompting DFO in June to close the majority of the province's commercial salmon fisheries. Photos: Sockeye salmon swimming upriver to spawn by Marco Tjokro / Unsplash. Sumas River, a tributary of the Fraser, by Jen Osborne / Canada's National Observer

“What cannot be debated is that most wild Pacific salmon stocks continue to decline at unprecedented rates,” said Jordan in a June statement announcing the closures. “We are pulling the emergency brake to give these salmon the best chance at survival.”

But while climate change and habitat destruction are partially to blame for the low stocks, critics say the way DFO stewards salmon fisheries in B.C. is also responsible and that the department must change its ways.

What cannot be debated is that most wild Pacific salmon stocks continue to decline at unprecedented rates.

Former federal fisheries minister Bernadette Jordan

Ned and Hope want First Nations to have equal authority alongside DFO to manage their nations' fisheries. As it stands, “(DFO) will listen to you, but that's about as far as it goes,” said Ned.

Until First Nations achieve equal footing, it will be impossible to craft conservation measures that blend science and traditional knowledge to support the fish and culture. It's a position the alliance said DFO has so far refused to accept.

That demand for autonomy echoes calls from Indigenous people across Canada for more control over natural resources on their lands in many sectors, including fish, forestry, and mining. While it is a position enshrined in the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), on the ground, efforts to gain greater agency have led to clashes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and government officials.

What drives the disconnect that we're seeing between Fisheries and Oceans Canada and many Indigenous peoples in this province and country is a deep sense of paternalism from DFO that stems from colonization.

Murray Ned, executive director of the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance

In B.C., the Nuu-chah-nulth nations, a coalition of five First Nations on Vancouver Island, have waged a 15-year legal battle against DFO for the right to conduct and manage their own commercial fisheries, including developing strict conservation measures. They won their case several times, including before Canada’s Supreme Court, but the nations say DFO continues to resist giving them equal authority. And in Nova Scotia, observers say one of the factors that fuelled a violent conflict last year that saw non-Indigenous harvesters attack Mi'kmaq harvesters' boats and fishing gear was DFO's years-long reluctance to work with Indigenous governments as equals.

Both of these conflicts focused on the nations' right to a commercial fishery, not a food fishery, which is for fish that can't be sold. But the underlying themes are the same, says Andrea Reid, a professor at the University of British Columbia and an Indigenous fisheries expert.

(DFO) will listen to you, but that's about as far as it goes.

Murray Ned, executive director of the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance

“What drives the disconnect that we're seeing between Fisheries and Oceans Canada and many Indigenous peoples in this province and country is a deep sense of paternalism from DFO that stems from colonization.”

The department refused an interview, citing the recent federal election. However, in a statement, it said, “First Nations are consulted on the management process for FSC fisheries throughout the Pacific Region, including the Fraser. DFO considers all input received from First Nations and, where possible, includes them in decision-making processes. This includes … factors such as starting times, gear types and methods, (and) fishing sites and areas.”

That's similar to the level of consultation DFO conducts with sport fishers, Ned explained. And even they say it's not enough.

Nathan Bootsma is a rarity among sport fishermen: The co-chair of the Fraser River Sportfishing Alliance (FRSA) is only 30 years old.

“I go to these (FRSA) meetings and I'm the youngest guy in the room every time,” he said, chuckling over the phone line. Fishing has always been his passion. He started as a kid, angling for trout and salmon in creeks in the B.C. Lower Mainland and his love for the sport has never waned.

Sport fishing is big business in B.C., worth more than $1 billion each year, according to the B.C. Chamber of Commerce. However, the fishing has been relatively sparse for anglers plying the Fraser River in recent years due to low numbers of returning salmon and steelhead trout. Photos: Fly-fishers casting their lines on a river in Alaska, where salmon are more plentiful, by Austin Neill / Unsplash. A rod waits for its owner by the Sumas River by Jen Osborne / Canada's National Observer

I wouldn't say it's sport fishermen versus First Nations fishermen. It's really all of us coming together.

Yet the past few seasons have been tough. While the September opening for pink salmon was a welcome surprise, sockeye salmon have been off-limits for years. There have also been only a few openings for chinook salmon in an effort to try to revive the stocks. With some of this year's chinook salmon runs being stronger than expected, he acknowledged the limits have been frustrating but haven't caused conflict on the water. If anything, they've proved fertile grounds for collaboration.

“I wouldn't say it's sport fishermen versus First Nations fishermen. It's really all of us coming together — commercial, First Nations, and recreational fishermen — saying we need DFO to manage this resource better,” Bootsma said, noting the three groups are trying to create a coalition that would make it easier to negotiate with DFO on conservation measures and fisheries openings. First Nations should still have priority access to the fish, he added.

There's a lot of talk about UNDRIP and reconciliation. They're all words to me: Unless we see action, it's lots of talk.

Murray Ned, executive director of the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance

A central part of those efforts will be pushing the DFO to consider research and knowledge from sources outside the department, like third-party research of anglers' observations of the fish, as it strives for conservation. Currently, DFO is reluctant to seriously consider external research or knowledge, despite regularly consulting sport fishers through a dedicated advisory group, the Sport Fishing Advisory Board, Bootsma said.

Changes could be on the horizon. In a June report on the crisis facing B.C. salmon, the federal Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans recommended DFO “recognize the decision-making authority of First Nations and work with them on a nation-to-nation basis … to plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate salmon management from egg stage to spawning phase.”

As a teenager, Hope said she took her summers fishing for salmon and learning important skills and cultural knowledge for granted. Now, she wonders how her son will learn those same lessons with so few opportunities to get on the river and fish. Photos by Jen Osborne / Canada's National Observer

The report called for broader changes within DFO that would require the department to “braid” traditional knowledge with Western science and create Indigenous guardian programs to support First Nations' habitat restoration and salmon protection efforts. Future salmon restoration efforts should be primarily led locally, with extensive collaboration between DFO, sport and commercial fishers, and First Nations. Community fish hatcheries, which can boost the number of fish available for recreational and commercial fishing, should also be supported, the report noted.

Furthermore, DFO in May announced a new $647-million management approach for Pacific salmon. While the Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative is still in development, the department earmarked funds to support habitat restoration, better collaboration, and a handful of other initiatives.

DFO could not comment on the report or any future changes to its management approach for Pacific salmon as Canada does not currently have a sitting federal government or fisheries minister.

“Everybody wants to maintain how they connect to salmon, which is very important,” said UBC’s Reid. “But when everyone is at this table and asking for their piece, we take this approach that's perhaps too small for the scale of the problems, (and) I think we're not finding solutions that are commensurate with that scale.”

Whether the plan will result in major changes remains to be seen. Over his career working to conserve salmon and Indigenous fisheries, Ned has heard countless federal fisheries ministers promise to transform DFO's approach in the name of reconciliation. Yet despite years spent meeting with government officials, he said little has changed on the water.

“There's a lot of talk about UNDRIP and reconciliation. They're all words to me: Unless we see action, it's lots of talk.”

[Top photo: When Sally Hope and Murray Ned were teens, they spent summers on the Fraser River fishing salmon. Now, they're lucky to get out for a few days each season to catch fish for food due to dwindling stocks. Photo by Jen Osborne / Canada's National Observer]