Articles Menu

Feb. 2, 2023

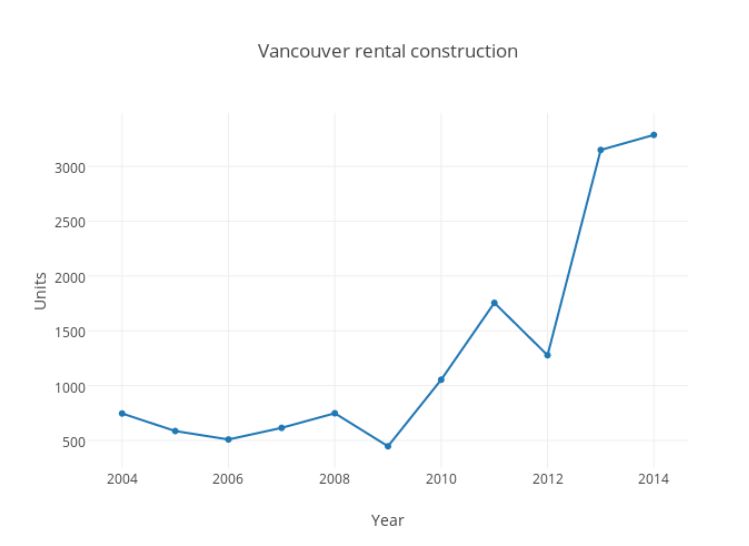

Over the past number of years, the City of Vancouver has proudly touted its accelerated construction of “purpose built rental housing” (housing units built to exclude individually owned units). They have reason to be proud. Since the early 2000s, the production of purpose-built rental units has risen by over 500 per cent.

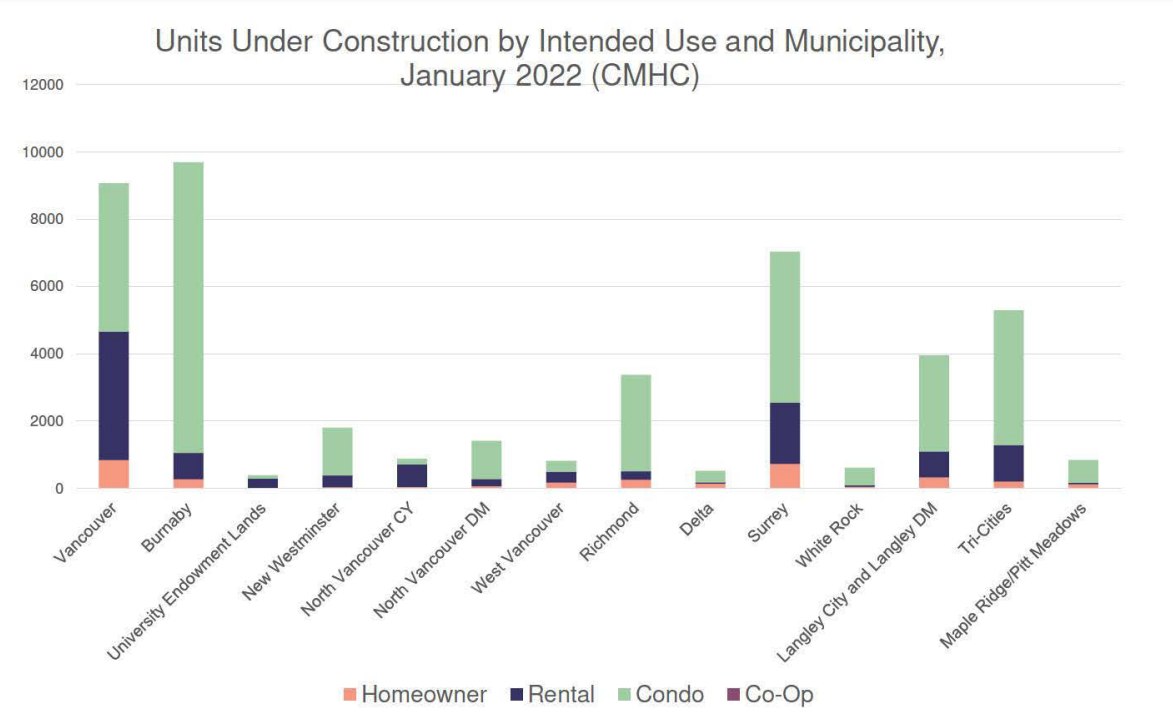

Rentals are projected to soon constitute the majority of the city’s new housing construction — vastly outpacing the rest of the region.

Less cause to celebrate is the lack of evidence that this is leading to the hoped-for reduction in rental rates. The city and many others argued that a dramatic increase in the new supply of rental housing would, to the extent that this reduced a scarcity of rental housing supply, lead to at least a slowing of dramatic recent rental costs and open up older apartments for new occupancy by middle-income wage earners.

The expectation was that adding new rental supply would lead to increased competition between landlords and thus lower rents.

Another key assumption was that adding brand new higher cost rental units would free up moderately priced older units in a process called “filtering.”

So it is more than disappointing to learn, via a new report from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. that not only has this laudable burst of rental housing not stemmed the rapid rise in our average rental cost, but seems to have the opposite effect of what the “filtering” advocates presumed. Quoting the CMHC from their section on Vancouver’s crisis:

“Interestingly, average rents for new two-bedroom units ($2,823) were nearly identical to the asking rent ($2,865) for vacant two-bedroom units of all ages. Rental demand is such that owners of existing units can, in some cases, seek rents that are equal to those for new units.”

Those findings would seem to throw into question, so far at least, where the “supply and demand” and the related “filtering” hypotheses are valid.

What we know are that new two-bedroom units, newly abundant in relative terms, are unaffordable to average renters — median household income of renter households is around $50,000, meaning rents above $1,300 per month are unaffordable. At the same time, the rents in “recently vacated” units have largely jumped up to unaffordable market rents matching rents in newly built units.

It’s worth placing this failure into its larger context. Both of these hypotheses — that competition and “filtering” necessarily drive down rents — are free market canons that have, since the 1980s, influenced local housing policy. Prior to what some call the “Reagan/Thatcher” revolution (Mulroney should be included), policy officials in Vancouver recognized that a fully “free market” in housing was not capable of providing housing for all the working families who needed it. In response Vancouver built thousands of co-op units.

But this all started to change in the 1980s when leaders embraced an alternative rationale. The reason you can’t afford housing, they said, is because the free market for housing is blocked by restrictive “externalities” that impede the free flow of supply to demand — and that if all these troublesome externalities were removed, everyone making a market wage could afford some form of market housing.

Well, you be the judge; but I think the evidence is in. We tried really hard, hoping it would work. It didn’t.

Why didn’t this pan out? The short answer is that the asset value of urban land has exploded globally, and this affects rents too. But that’s a much longer story. The main point here is that it didn’t work. So now what do we do?

I say let a thousand flowers bloom. All ideas not grounded in fully disproven premises should be entertained. But my preferred approach is this: Don’t just “up-zone” for new density hoping that new supply will lead to affordability (it won’t), but insist that up-zoning for new density be contingent on affordability.

Is this practical? Yes. We are already doing this. The Downtown-Eastside/Oppenheimer plan has proven that you can zone for affordability, in this case mandating it over 50 per cent of units, and still have projects get built.

The reduced market value of the project is mitigated by the reduction in land price (via a lower “land price residual”) to the developer. Land price now constitutes up to two thirds of total development costs in the City of Vancouver. Any social benefit demand applied by the city, in this case adding less expensive housing, will affect the project “proforma” and put downward pressure on the price developers can pay for land — land prices that have exploded by as much as 1,000 per cent in recent years.

Under these circumstances, it is both reasonable and practical to extend this requirement to the rest of the city. This will further reduce land speculation while insuring that at least half of the units are available at a price that our wage earners can afford.

Or, on the other hand, we can continue to sacrifice the futures of our children and the service workers who make this city run to the false gods of “supply and demand.” Good luck with that.

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture.

[Top photo: ‘A key assumption was that adding brand new higher cost rental units would free up moderately priced older units in a process called “filtering.”’ Photo by David Beers.]