Articles Menu

Nov. 2, 2025

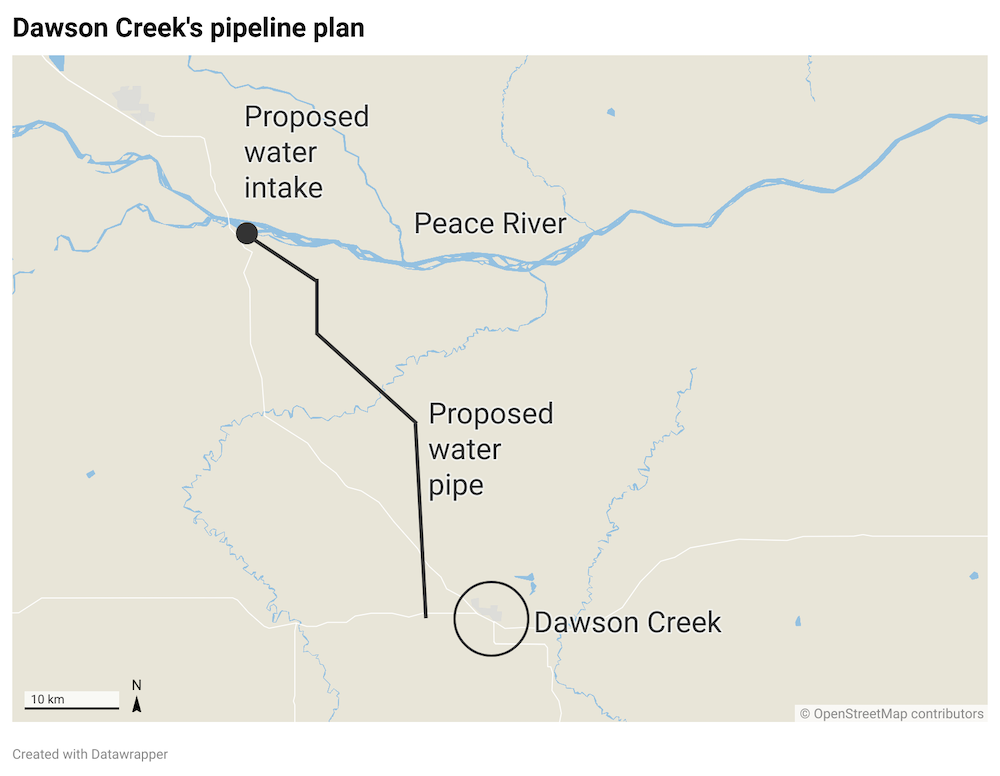

The projected cost of a $100-million water pipeline stretching more than 50 kilometres from the Peace River to drought-stressed Dawson Creek is nearly five times greater than what the city received in property tax revenue last year.

But the city says the costly pipeline is urgently necessary. Water levels on the nearby Kiskatinaw River, Dawson Creek’s only source of drinking water, have fallen to points never before recorded. Even with the city instituting water restrictions and residents and businesses reducing consumption, the city has been forced to declare a state of emergency.

The declaration opens the door for provincial funding of a stopgap measure: the laying of thick, industrial-grade hoses and pumps that could carry water from the Peace to the drought-stressed city. But the proposed long-term fix — that buried, large-diameter, $100-million pipeline — brings a bigger question: Why should city taxpayers foot the bill, when the biggest user of that water will likely be oil and gas companies?

In a proposal submitted to B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office, Dawson Creek says the proposed pipeline would convey 10 million cubic metres of water per year, an amount three times greater than what the city uses.

Two-thirds of that water could then be sold, generating revenues that would pay for the project. The biggest likely buyers are oil and gas companies that have water challenges of their own as they ramp up fracking operations that now consume on average nearly 10 Olympic swimming pools’ worth of water at each fracked well. That’s 20 per cent more water per well than just four years ago. And that’s before fracking operators, who pump massive amounts of water, sand and chemicals underground to liberate gas and oil, increase operations to supply a massive methane gas processing and export facility in Kitimat.

With it likely that oil and gas companies would use the lion’s share of the water, the provincial government has a vital role to play in Dawson Creek’s emergency. It has authority both to manage water resources in the best interests of all British Columbians and to regulate fossil fuel companies that cannot maintain, let alone expand, operations without consuming copious quantities of water.

The current drought in the heart of the most actively fracked zone in B.C. is all the justification the province needs to exercise its powers and order fossil fuel companies to pay for the proposed water line. If it chooses to, the province can ensure that Dawson Creek’s residents don’t pay a dime for the line.

Two fateful decisions

As Dawson Creek turns to the distant Peace River to solve its drought problems, it is worth considering what brought us to this pivotal point.

In the early 1960s the then-Social Credit government greenlighted construction of the W.A.C. Bennett Dam. Completed in 1968, the giant earth-filled structure created Williston reservoir, which remains the world’s seventh-largest artificial lake by water volume.

Two other dams — Peace Canyon and Site C — followed. All three provided critical power to residents and businesses throughout much of B.C. But the structures forever changed the face of the Peace region, obliterating some of Canada’s most productive farmland, destroying wetlands that were once critical stopovers for migratory birds, and wiping away countless opportunities for First Nations to hunt, fish and carry out cultural practices that they were told would be protected when they signed Treaty 8, the 1899 land deal between the Crown and First Nations east of the Rockies in B.C., Alberta and Saskatchewan. As spelled out in a landmark 2021 B.C. Supreme Court decision, those promises were broken.

That decision came after the Blueberry River First Nations sued the provincial government, arguing it had allowed thousands of industrial developments to occur within their territory without considering the cumulative effect on the First Nations’ rights.

In her ruling in favour of the First Nations, Chief Justice Emily Burke noted that the BC Oil and Gas Commission had not once “denied a permit due to anticipated impacts on the Plaintiffs’ treaty rights.” In fact, the provincial government did just the opposite:

“The evidence shows that the Province has not only been remiss in addressing cumulative effects and the impacts of development on treaty rights, but... it has been actively encouraging the aggressive development of the Blueberry Claim Area,” Justice Burke found.

Such rights extended, of course, to water resources in the claim area, which raises questions about how the government and its energy regulator are managing water in the broader area where the fracking industry operates.

Scientists have known for decades that the Peace region would get warmer and drier, as would the rest of Canada’s vast boreal zone. But rather than heed the warnings, one B.C. government after another twisted itself into knots arguing that using more “clean” hydro to power more methane gas production amounted to a climate solution. Such arguments have also been happily parroted by industry.

What neither the government nor industry says is that while hydro can be used to displace the use of methane gas in compressors and other gas industry equipment, the gas saved does not magically stay in the ground. It goes into the pipeline and is ultimately burned by customers. At the end of the day, there are no savings.

All-in on methane gas

At this stage, with even more LNG plants approved and more proposals in the works, no one should expect the provincial government to do an about-turn on LNG production. That tanker ship has already sailed. So, with B.C. all-in on methane gas, what can the province do to blunt the significant impacts on the Peace region’s waterways, stressed farmlands, ecosystems and First Nations?

Part of the answer is captured in Dawson Creek’s water proposal itself. The Peace River is the region’s largest river. Taking water from it would have far fewer social, environmental and economic consequences than sourcing water from smaller drought-stressed or at-risk rivers.

If it chose to, the provincial government could use the Dawson Creek proposal as a catalyst to say that the fracking industry as a whole must refrain from using water from small, vulnerable water courses and instead take all its water from the Peace River and its three giant reservoirs.

The undammed rivers are in trouble enough as it is, and the troubles will only deepen in the face of accelerated industrial water withdrawals.

One such river currently in the headlines is the Kiskatinaw. The river flows near Dawson Creek and is a tributary of the Peace. It is heavily reliant on rainfall and melting snow from surrounding lands and is not fed by the larger snowpacks that accumulate in mountains. If less snow or rain falls due to drought, that translates into plummeting water levels. Similar conditions prevail with other rivers in the Peace region including the Pouce Coupé, Blueberry and Beatton rivers.

In addition to the City of Dawson Creek holding a water licence on the stressed Kiskatinaw, two oil and gas companies — Ovintiv and Murphy Oil — hold water licences of their own. Two years ago, as the river’s levels started dropping due to drought, conditions in the companies’ water licences forced them to dramatically scale back their withdrawals. Last year, with the drought conditions continuing, they were prevented from taking any water at all.

The Kiskatinaw’s flow has declined so drastically that it has reached the lowest point since records were first kept 61 years ago.

If the Romans could do it...

Just as a water pipeline from the Peace would assist the City of Dawson Creek, so too would it help Ovintiv, Murphy Oil, Shell Canada, Canadian Natural Resources, ARC Resources, Tourmaline and other fossil fuel companies operating in the Montney basin, which straddles the B.C.-Alberta border and is Canada’s most important repository of methane gas and light oils.

The companies will be incentivized to frack even more to meet the additional demands of LNG Canada, B.C.’s first major methane gas liquefaction facility, which commenced overseas exports in June. Exports from that facility come on top of the significant amounts of gas routinely exported to Alberta and the United States. That means more water must be used. And because fracking turns fresh water into a toxic soup of salt, metals, hydrocarbons, carcinogenic compounds and even radioactive elements, it cannot be discharged back to the rivers and streams from which it came.

The same companies also need copious amounts of water to frack underground shale rock formations rich in light oils such as condensate, a prized liquid used by Alberta’s tarsands industry to dilute the thick bitumen that is now shipped via the Trans Mountain pipeline, the most expensive publicly funded infrastructure project in Canadian history, to tidewater in Burnaby for ocean transport.

Companies that aggressively drill and frack in liquids-rich formations in the Peace region have made off like bandits in recent years. ARC Resources’ most recent annual report boasts of distributing $627 million to its shareholders in 2024, driven largely by water-intensive light oil production near the Halfway River, a tributary of the Peace.

With that kind of money, ARC and other companies can afford to pay their fair share for new water infrastructure.

The province has all the powers it needs to order the companies to pool their resources and money to rapidly build out a shared network of major water pipelines, branch lines and water hubs that would tap water from the Peace River or its reservoirs.

If the Romans two millennia ago could build aqueducts stretching hundreds of kilometres to meet their imperial ambitions, the empire of oil can do the same.

That would mean creating major water pipelines running both south toward Dawson Creek and north into the heart of B.C.’s most actively fracked areas. Water pipelines could also be built east from the Williston reservoir as needed.

Oil and gas companies already hold water licences on the river and the reservoir. Water to meet the needs of Dawson Creek could be carried down new pipelines. When the frackers are gone, the city could assume responsibility for maintaining the line.

Toxic waste and recycling

In addition, the provincial government has powers to order oil and gas companies to reuse all the wastewater generated at fracking operations and pay stiff penalties if they do not. This recycling requirement has recently been proposed by the environmental organization Stand.earth.

Typically during fracking, roughly between one-third and two-thirds of the water pumped underground with earthquake-inducing force eventually flows back to the surface. The industry itself acknowledges that the wastewater can be reused following treatment. But this requires maintaining a large network of storage reservoirs to retain the toxic flow-back water before it is treated. The 50 per cent increase in the oil and gas industry’s withdrawals of fresh water for fracking between 2023 and 2024 suggests that much of this wastewater is not being reused.

If such reuse is to be ramped up in a significant way, it will require significant regulation and government oversight, as such storage reservoirs have leaked to contaminate soil and groundwater with carcinogenic and radioactive compounds.

Build, build, build

While Dawson Creek’s emergency declaration underscores the need for urgent action, the bigger reason for reforms has to do with what lies ahead.

The Peace region, heavily industrialized as it already is, is on the cusp of what will be an unprecedented and sustained increase in fracking operations for decades to come.

The increased activity is the result of the recent opening of the $40-billion LNG Canada facility near the community of Kitimat. The plant, which turns methane gas into super-cooled liquid that can be loaded onto ocean vessels, shipped its first tankerload of liquefied gas in June.

The landmark shipment — the first sizable liquefied gas export from Canada — is just the beginning. Three more methane gas liquefaction facilities are already approved in B.C.: one in Squamish, another in Kitimat and a third in Gingolx, a Nisg̱a’a Nation community in the north.

The three facilities alone have capacity to process and ship 15 million tonnes of fracked gas per year, effectively doubling what LNG Canada can distribute. Meanwhile, LNG Canada itself is considering a second phase to its project that would double its capacity. All of these plants will require methane gas from the Peace region, necessitating an unprecedented and sustained increase in gas drilling and fracking operations that could have grave economic and environmental consequences, energy analyst David Hughes told The Tyee last year.

And it’s still not enough for some. “We should have 15 of these things up and running,” federal Conservative party leader Pierre Poilievre told Global News in mid-September when Ottawa approved the Ksi Lisims LNG project on Nisg̱a’a land.

A cautionary tale

Whatever the number of such plants, it is worth reiterating that none of this happens without water, which is already emerging as a central challenge for another North American energy hot spot: Corpus Christi, Texas.

The eighth-largest city in Texas now confronts a crisis that serves as a cautionary tale for what may lie ahead for B.C.’s parched Peace region.

In the last decade, companies have spent $57 billion to construct a slew of very large industrial complexes within Corpus Christi’s city limits. The projects included a new ethylene plant, a new Tesla lithium refinery and a massive new plastics facility built by Exxon and Saudi Basic Industries Corp.

These plants and others all required significant volumes of water. Roughly half of all the water consumed in the city now goes to just eight companies. As the plants multiplied, a drought intensified, leading to a rapid decline of water in Corpus Christi’s reservoirs. The city now confronts the possibility of exhausting its water supplies by the end of 2026 unless something is done.

“The water situation in South Texas is about as dire as I’ve ever seen it,” Mike Howard, CEO of a private energy company with a number of facilities in Corpus Christi, told the Wall Street Journal in early October. “It has all the energy in the world and it doesn’t have water.”

The city seriously weighed the possibility of building a sea water desalination plant. But the cost of doing so was a prohibitive $1.2 billion, and in early September the city’s council voted to reject the plan.

Instead, the city announced in October that it was moving in a different direction and was buying existing rights to groundwater beneath 23,000 acres of land north of the city. But that choice will not be cheap either and is estimated to cost in the neighbourhood of $840 million by the time the necessary infrastructure is built.

The project’s formidable costs are not the only concern. Farmers north of Corpus Christi worry the deal will leave them with far less water to irrigate their crops and that the water they do have will become saltier.

All of this, it is worth noting, is occurring in the state that gave birth to the fracking revolution.

As B.C. goes all-in on fracking, it would be wise to take note.

If the provincial government is going to insist that the Peace region’s finite fossil fuels be wrested from the ground for export, then the very least it can do is to put in place a water plan that does the least possible harm to local residents and communities and that gives undammed and uncompromised rivers and creeks a fighting chance as temperatures continue to climb and less rain falls.

[Top photo: Dawson Creek’s proposed water pipeline would include an intake on the Peace River, across from the gas plant in Taylor, BC. Photo by The Tyee.]