Articles Menu

Website editor: A good article.

Dec. 11 2023

The year is 2040. Aided by millions of dollars in subsidies, electric vehicles have taken over the streets. Tailpipe smog and engine revving are a distant reminder of a less civilized age, replaced by the low hum of battery-powered motors whizzing their occupants across town. We slowed climate change, and we got to keep our habit of buying new, shiny things. A habit that probably got us here in the first place.

This is the future envisioned by politicians of all stripes across B.C. Environmental activist and Green Party MP Elizabeth May and oil pipeline superfan Christy Clark both agree: electric vehicles are heckin’ cool.

But if we could just peer past the haze of flashy advertisements and photo-ops, we’d see EV rebates for what they are: a handout of millions of dollars of public money to help the wealthy buy new cars.

Big investment, but where’s the impact?

The wholehearted, pan-partisan support of EV adoption has created a vast pool of public money dedicated to helping British Columbians roll out of the lot with their very own brand-new climate-fighting automobile. In the years since the CleanBC Go Electric passenger vehicle rebate program has been active, 54,000 rebates have been issued, igniting a sharp increase in EV purchases. Between 2016 and 2022, 80,000 new EVs hit B.C. roads.

As of this writing, individuals earning up to $80,000 a year receive $4,000 towards the purchase of EVs with a manufacturer’s suggested retail price of up to $70,000. By B.C.’s own figures, 90 per cent of B.C. residents are eligible for this rebate. In Vancouver, if the estimated 600,000 eligible people took the government up on its offer, taxpayers would be on the hook for $2.4 billion, coming close to the cost of a new subway along Broadway.

Let’s do a math exercise. In B.C., the median after-tax household income is about $60,000 per year. A quick search pins the Nissan Leaf as the most affordable EV on the market in Canada, at around $40,000 for a base model. For a median-wage earner, the post-rebate purchase cost of the Leaf comes to $36,000, over half their yearly income. And that’s before the cost of maintenance, insurance, parking and charging.

Who is this rebate helping? It is certainly not helping people on the bottom half of the income scale, or those struggling to make ends meet. The irony is not missed when you consider that carbon emissions are directly related to personal income: the more money you make, the more carbon you emit.

The Tyee recently ran a story about a single mother making over $80,000 who was unable to afford a new EV as her income was too high for the $4,000 rebate. Yet B.C.’s rebate system still offers $1,000 for individuals making up to $100,000. An income over $100,000 is in the top 10 per cent of earners in the country.

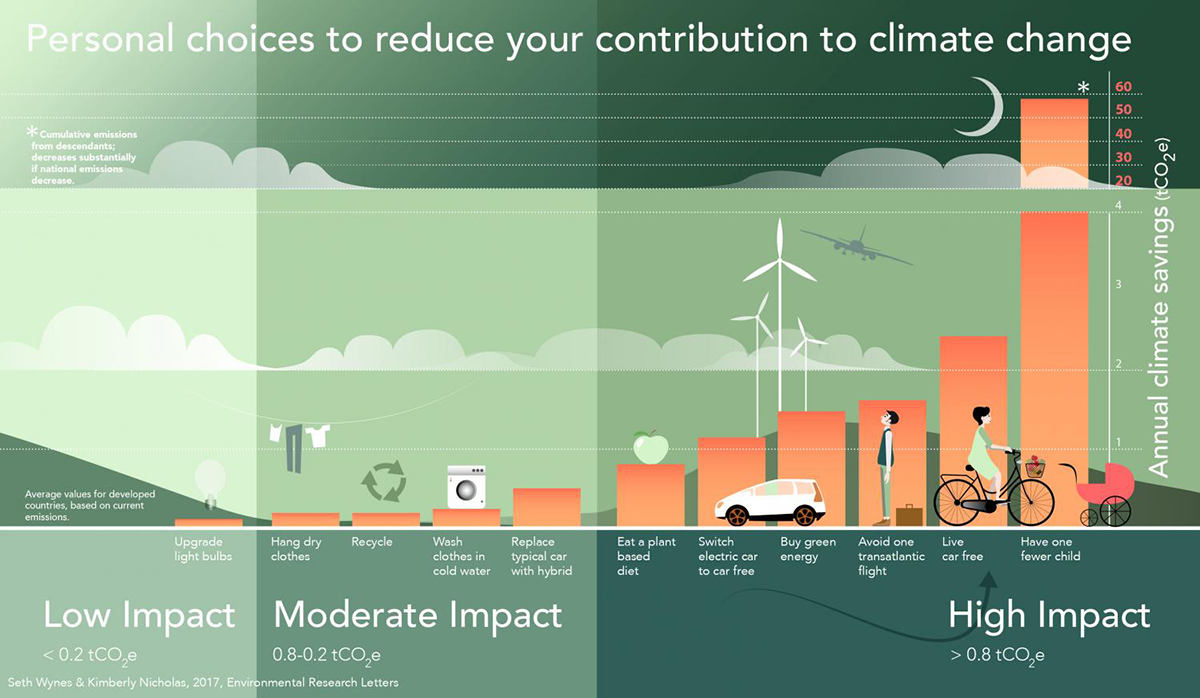

I question why even a dollar of the public’s money should go towards helping people — especially high earners — buy a new private car under the guise of climate progress. There is a somewhat shaky consensus that EVs are greener than conventional cars. However, the net decrease in emissions that results from a conventional-to-electric vehicle swap pales in comparison to choices like investing in green energy, taking one less flight and living car-free.

What would a science-backed, ethical climate rebate system look like?

Often touted as a silver-bullet to transportation emissions, EVs raise ethical concerns that are seldom discussed but should become more widely understood as they continue to rise in popularity.

On a global scale, the rapidly increasing demand of the rare earth metals required for EV batteries is fuelling human rights abuses in the places where they are mined. This disturbing fact is often glossed over in the name of climate progress. Incentivizing private vehicles over public transit further perpetuates issues associated with cars — electric or not — like urban sprawl, congestion and pedestrian fatalities.

I’m also curious about the ethical tensions that arise when we ask whether governments should use taxpayer money to reward personal climate action. This is at the heart of the EV rebate system, and to me, the rewards seem unevenly distributed. We don’t, for example, provide incentives to people who give up meat, even though a landmark meta-analysis showed that a switch to a plant-based diet cuts more carbon emissions than switching to an electric vehicle.

And there are no rebates to go car-free by taking transit, cycling or walking to work. What about my reusable water bottle? Why don’t I get a rebate for that, too?

All of this sparks an interesting conversation: what would a science-backed, equitable climate rebate system look like?

We could pay people to live car-free. That’s an idea that Vancouver Mayor Ken Sim floated in ABC Vancouver’s since-deleted 2022 climate platform and already in action in California.

We also could make a car-free lifestyle more accessible by expanding fare-assistance programs like the BC Bus Pass and accessible transit options like handyDART. We could immediately make small-scale transit improvements like extending bus schedules, adding new routes, or making trains more frequent: goals that would be more achievable over a short term with less investment compared to bigger projects like rapid transit expansions.

There are policy changes that could encourage people to eat less meat. We could promote plant-forward diets by holding more veg-fests and fewer rib-fests. We could introduce progressive taxes on large meat companies and provide subsidies for local produce growers like City Beet Farm and Sole Food Street Farms.

The meat and dairy industry have spent billions to create marketing campaigns that are now deeply ingrained into our cultural consciousness (remember “Got Milk?” Or bacon mania?). Subsidies for fruits and vegetables could do the same for spinach and lentils, benefiting public health, reducing carbon emissions, and reducing health-care costs to society.

EV rebates show us that the B.C. government is making a concerted effort to incentivize greener lifestyle changes. We must ask, though: who will benefit from these incentives? Will it be all of society, or only some? As we transition to a post-carbon world, EV rebates show us the real danger of creating a future where some people reap the benefits of a green transition and others — most often the less fortunate — are left behind.

Auston Chhor is a biologist and science writer living in Vancouver.

[Top photo: Who are electric vehicle rebates really helping? And what could we do to make government-subsidized climate action more equitable? Photo via Shutterstock]