Articles Menu

Apr. 21, 2023

Successive British Columbia governments have portrayed the province as a climate change leader, but since 2005 six other provinces have been more successful than B.C. at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

“The distinction is between saying that we have a climate plan, which is what we hear from this government a lot, and the actual data on our emissions,” said Sonia Furstenau, leader of the BC Green Party and MLA for Cowichan Valley. “A plan is only as effective as the outcomes and if we aren’t seeing a significant decrease in our emissions, then that plan appears not to be working.”

Last Friday, the federal government released its 2023 report, the “National Inventory Report 1990-2021: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada.”

The national results were widely reported as positive — even if they are far short of what’s needed to meet international commitments, with a slight increase in 2021 that still kept the country’s emissions 7.4 per cent below the pre-pandemic levels seen in 2019 and 8.4 per cent below what they’d been in 2005.

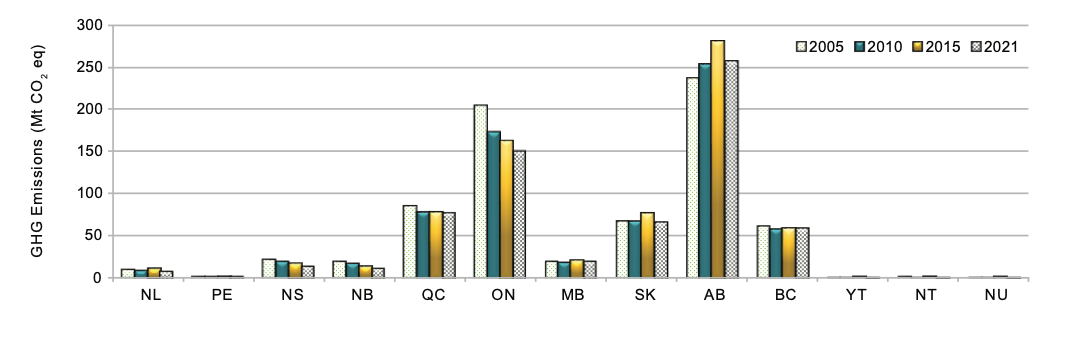

But at the provincial level, there was a wide variety in performance.

At one end was Alberta, which increased its already largest-in-Canada emissions by 8.6 per cent between 2005 and 2021. Manitoba and two of the territories also had increases.

With a 3.6-per-cent decrease, B.C. made a slightly bigger reduction in emissions than Saskatchewan, but trailed Quebec (9.4 per cent), P.E.I. (13 per cent), Newfoundland and Labrador (18 per cent), Ontario (26 per cent), Nova Scotia (36 per cent) and New Brunswick (39 per cent).

According to report, the variation among provinces and territories is affected by factors like population, energy sources and economic structure. “All else being equal, economies based on resource extraction will tend to have higher emission levels than service-based economies,” it said. “Likewise, provinces that rely on fossil fuels for electricity generation emit relatively higher amounts of GHGs than those using hydroelectricity.”

George Heyman, the province’s minister of environment and climate change strategy, said a couple of key factors need to be kept in mind when looking at B.C.’s performance.

For one thing, almost every other province was using fossil fuels for electricity generation, and making a switch to cleaner power is a relatively easy way to reduce emissions, he said. B.C.’s electricity already came almost entirely from hydro which produces very low emissions, so that option wasn’t there for the province.

That means B.C. has to find emission reductions elsewhere, Heyman said. “What we’re focusing on are some of the harder to abate emissions that are intrinsic to a number of industrial processes, [and] also have to do with transportation, which you can’t change up overnight, as well as emissions from heating and cooling buildings.”

There are significant policies and programs in place, many of which were introduced in 2018 and began getting implemented in earnest in 2019, he said, giving examples like the move to zero emission vehicles, zero carbon buildings and caps on emissions.

“There’s a lot of areas we have to take action in and we can’t afford to not take action in any of them, but we’re trying to take action in all of them,” Heyman said. “That is what I think we expect to be held to account for.”

Another key factor, the minister said, is that B.C. has had stronger economic growth and a faster growing population than other provinces.

“That obviously adds to emissions,” he said. The government’s commitment is to reduce total emissions, not emissions per capita, he stressed, but he added, “In the short term those are factors we’ve had to deal with.”

Katya Rhodes is an assistant professor in the University of Victoria’s School of Public Administration and an economist focused on climate policy. From 2016 to 2019 she provided economic analysis and advice to the provincial government’s Climate Action Secretariat.

B.C. has now put good policies in place that are just beginning to work, Rhodes said. “Without climate policy the emissions would have been higher.... These avoided emissions are huge, they’re just not very visible.”

While the results in other provinces seen in the national inventory report provide interesting contrasts, it isn’t necessarily fair to make direct comparisons, she said, noting that each was starting from a different baseline and have varying levels of commitment.

“We have a huge buy in with the current government in British Columbia,” Rhodes said, adding that federal climate policies will also have an impact across the country. “I think it will be exciting to see what the next inventory report shows to us in the future years and how the government interprets whatever happens with emissions.”

Mark Jaccard, the director of the School of Resource and Environmental Management at Simon Fraser University, said there’s been debate among climate modellers about what the numbers in the inventory report mean.

In particular, he said, it’s surprising to see Alberta’s emissions starting to drop even as oilsands production continues to spike upwards, something he attributes to the effect of carbon pricing and other policies outweighing increased oil and gas emissions.

“I think it’s a big deal,” he said.

When comparing B.C. to the Maritime provinces, Jaccard said, it’s important to keep in mind that B.C.’s population has been growing much faster, leading to more vehicles on the roads and more carbon emissions.

In Ontario, he said, the main cause of the drop in emissions was the phasing out of coal-fired power by Dalton McGuinty’s Liberal government, along with the closing of energy intensive companies including steel makers and manufacturers.

“When you have those things close, your emissions go down,” Jaccard said, adding that sawmills and pulp mills that have closed in B.C. weren’t as emissions intensive. “In B.C., you can lose some industry and your emissions won’t go down.”

After controlling for population and economic growth as well as several years of inaction under former premier Christy Clark’s government, he concluded, B.C.’s results are actually pretty good. “I’m encouraged by a flat line in British Columbia,” he said. “We’re still dealing with that legacy that we didn’t do anything while the population kept climbing.”

The current NDP government appears to be sincere about cutting emissions and has introduced policies that are having an effect, he said.

The Sierra Club BC said the failure to reduce emissions, and choices the province has made, make it unlikely the province will meet its targets.

“Issuing permits for new fracked LNG infrastructure at a time when alternatives are readily available is incredibly shortsighted,” said Jens Wieting, senior forest and climate campaigner. “The open question is whether we can change course faster than the climate is now changing, after all the damage we have already caused.”

In 2021 the B.C. government released a Roadmap to 2030 that built on the earlier CleanBC plan to show how it would meet the legislated goal of a 40-per-cent drop below 2007 levels by 2030.

Critics argued the plan would fail as long as the province continued to encourage the oil and gas sector to grow, though government officials have said any new development would have to fit within the climate plan and has since promised to cap emissions from the sector.

B.C.’s climate change accountability law requires deeper cuts by 2040 and 2050. The government missed a previous goal of a 33-per-cent reduction by 2020, with emissions instead remaining more or less unchanged from 2007 levels.

Heyman said the province’s plan is complex and involves multiple pathways across different sectors. “We know we have to do a lot,” he said. “We need to stay purposeful and ensure we have the sense of urgency that the people who are concerned about climate change have.”

He hopes, he said, people will look at how the province is making progress and the government’s willingness to be transparent about what it’s doing and the results it is getting.

Andrew MacLeod is The Tyee’s Legislative Bureau Chief in Victoria and the author of All Together Healthy (Douglas & McIntyre, 2018). Find him on Twitter or reach him at amacleod@thetyee.ca.

[Top photo: Critics warn that as long as the oil and gas sector continues to grow, BC won’t meet its emissions targets. Photo via Coastal GasLink.