Articles Menu

Apr. 27, 2023

The water supply crisis is threatening the future of this important maritime route which links the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Around six per cent of all global maritime shipping passes through the canal, mostly from the US, China and Japan. For the fifth time this drought season, which lasts from January to May, the Panamanian Canal Authority (ACP) has had to limit the largest ships passing through.

Alajuela and Gatun are the two artificial lakes that supply water to the Panama Canal. It requires around 200 million litres of water to flow down a series of tiered locks into the sea in order for each ship to pass through.

Rainwater is the source of these reserves that power the locks, which can be up to as much as 26 metres above sea level.

The ACP says that from 21 March to 21 April, water levels in Alhajuela fell by seven metres - more than 10 per cent.

“The lack of rainfall impacts several things, the first being the reduction of our water reserves,” Erick Cordoba, the ACP's water manager, told AFP.

It also affects business “with the reduction of the draft of Neopanamax vessels, which are the largest vessels transiting the canal” and the ones that pay the most tolls, he adds.

In 2022, more than 14,000 vessels with 518 million tonnes of cargo passed through the waterway, contributing $2.5 billion (€2.3 billion) to the Panamanian treasury.

Canal administrator Ricaurte Vasquez recently acknowledged to Panamanian website SNIP Noticias that water shortage was the main threat to shipping in the canal.

In 2019, fresh water supplies dropped to just three billion cubic metres - a long way short of the 5.25 billion needed to operate the canal.

It set alarm bells ringing for authorities who worry that uncertainty could lead shipping companies to favour other routes. The water crisis also has them searching for solutions.

It is vital to find new water sources, especially faced with the climate change we are seeing, not just in our country but all over the world.

“Without a new reservoir that brings new volumes of water, this situation will remove the canal’s capacity to grow,” former administrator Jorge Quijano told AFP.

“It is vital to find new water sources, especially faced with the climate change we are seeing, not just in our country but all over the world.”

The water crisis isn’t just affecting the canal, however. Shortages have led to supply problems in several parts of Panama and provoked a number of protests.

Experts warn that it could cause water conflicts between the canal and local populations.

“We don't want to engage in a philosophical conflict over water for Panamanians or water for international commerce,” said Vasquez.

The canal has suffered from “a lack of rain as we have had in the whole country, but within the parameters of what is a normal dry period,” Luz de Calzadilla, general manager at Panama's meteorology and hydrology institute, told AFP.

But the El Nino climate phenomenon is likely to reduce rainfall in the second half of the year, Calzadilla adds.

He says that there is a responsibility by law to prioritise drinking water over business but the canal administration “works magic” to maintain the balance.

It is little solace for those facing water shortages on Lake Alajuela.

“Alajuela has less water every day,” Leidin Guevara, 43, who fishes in the lake, told AFP.

“This year has been the most difficult I’ve seen for drought.”

Watch the video to see how water shortages are affecting the Panama Canal.

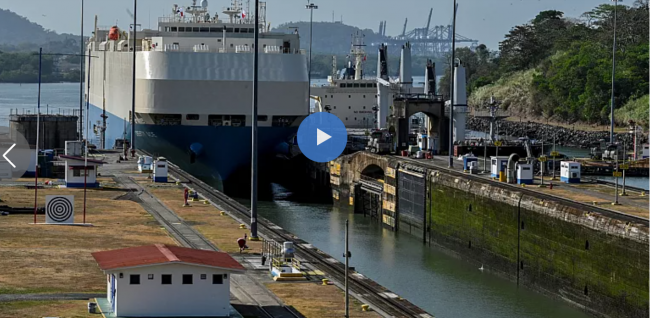

[Top: A ship is guided through the Panama Canal's Miraflores locks near Panama City]