Articles Menu

Feb. 9, 2024

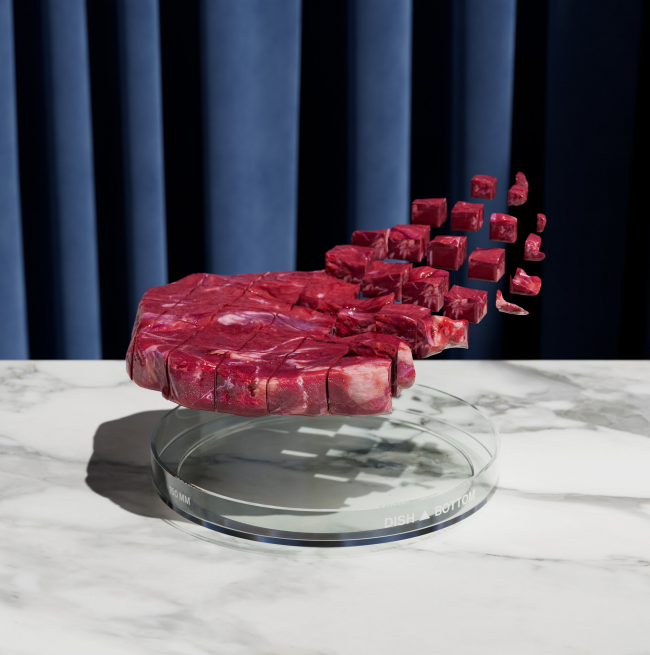

It is a gleaming vision of a world just beyond the present: a world in which meat is abundant and affordable with almost no cost to the environment. Animal slaughter is forgotten. Global warming is restrained. At the heart of the vision is a high-tech factory housing steel tanks as tall as apartment buildings and conveyor belts rolling out fully formed steaks, millions of pounds a day — enough, astonishingly, to feed an entire nation.

Meat without killing is the central promise of what’s come to be known as cultivated meat. This isn’t a new plant-based alternative. It is, at least in theory, a few animal cells, nurtured with the right nutrients and hormones, finished with sophisticated processing techniques, and voilà: juicy burgers and seared tuna and marinated lamb chops without the side of existential worry.

It’s a vision of hedonism — but altruism, too. A way to save water, free up vast tracts of land, drastically cut planet-warming emissions, protect vulnerable species. It’s an escape hatch for humankind’s excesses. All we have to do is tie on our bibs.

Between 2016 and 2022, investors poured almost $3 billion into cultivated meat and seafood companies. Powerful venture capital and sovereign wealth funds — SoftBank, Temasek, the Qatar Investment Authority — wanted in. So did major meatpackers like Tyson, Cargill and JBS, and celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, Bill Gates and Richard Branson. Two of the leading companies — Eat Just and Upside Foods, both start-ups — reportedly achieved billion-dollar valuations. And today, a few products that include cultivated cells have been approved for sale in Singapore, the United States and Israel.

Yet despite nearly a decade of work and a great many messianic pronouncements, it is increasingly clear that a broader cultivated meat revolution was never a real prospect, and definitely not within the few years we have left to avert climate catastrophe.

Interviews with almost 60 industry investors and insiders, including many who have been employed by or been part of the leadership teams of these companies, reveal a litany of squandered resources, broken promises and unproven science. Founders, hemmed in by their own unrealistic proclamations, cut corners, such as using ingredients derived from slaughtered animals. Investors, swept up in the excitement of the moment, wrote check after check despite significant technological obstacles. Costs refused to enter the realm of plausible as launch targets came and went. All the while, nobody could achieve anything close to meaningful scale. And yet companies rushed to build expensive facilities and pushed scientists to exceed what was possible, creating the illusion of a thrilling race to market.

Now, as venture capital dries up across industries and this sector’s disappointing progress becomes more visible, the reckoning will be difficult for many to survive.

Investors will no doubt be eager to find out what went wrong. For the rest of us, a more pressing question is why anyone ever thought it could go right. Why did so many people buy into the dream that cultivated meat would save us?

The answer has to do with much more than a new kind of food. For all its terrifying urgency, climate change is an invitation — to reinvent our economies, to rethink consumption, to redraw our relationships to nature and to one another. Cultivated meat was an excuse to shirk that hard, necessary work. The idea sounded futuristic, but its appeal was all about nostalgia, a way to pretend that things will go on as they always have, that nothing really needs to change. It was magical climate thinking, a delicious delusion.

Mr. Tetrick had been an animal-rights activist since high school, and he started Hampton Creek in part, he said, to save farm animals from short, brutal lives as flesh-and-blood cogs in a global supply chain. He also spoke movingly about how, by switching to vegan products, we could start reversing the greenhouse emissions, water crises and ecosystem damage caused by animal agriculture.

Getting carnivores to change their eating habits is an uphill battle. Despite the destructive impact of meat, we continue to eat huge amounts of it, behavior that Mr. Tetrick has likened to addiction. But back in law school, he read about something that piqued his interest: NASA-funded scientists had attempted to grow meat (goldfish meat, in that case) in a laboratory.

The idea didn’t gain traction until 2013, when a Dutch scientist named Mark Post announced he had brewed up the world’s first cultivated beef burger. The single patty, which was painstakingly grown strand by strand in hundreds of plastic dishes, cost more than $300,000 to develop. It wasn’t practical, but it was powerful: Soon cultivated meat start-ups were raising money, making bold proclamations and laying out aggressive product timelines.

The most basic part of the process — turning a few living cells into many — was not new. It’s what pharmaceutical companies had been doing for decades to make vaccines. Pumped-in oxygen and a rich soup of amino acids and sugars simulate the conditions the cells would encounter inside a body, and added hormones signal the cells to divide and multiply.

As expensive as that process is, it typically produces only “cell slurry,” a viscous mass. To turn it into something someone could eat (or sell), you’d need to mix in vegetable matter like pea and soy, for a kind of plant-animal hybrid. Or you could try something vastly more difficult: getting the animal cells to form into muscle-like tissue.

Making any of that happen affordably and at large volumes is a problem that even today no one has solved. That didn’t stop Uma Valeti, the founder and C.E.O. of the company that is today known as Upside Foods, from declaring, in 2016, that humanity was at the brink of the “second domestication,” a dietary shift as momentous as the shift from hunting and gathering to crops and livestock. “We believe that in 20 years, a majority of meat sold in stores will be cultured,” he told The Wall Street Journal. “In just a few years, we expect to be selling protein-packed” — and fully cultivated — “pork, beef and chicken,” he told The Washington Post. Inc. magazine profiled him as the cardiologist who “is betting that his lab-grown meat start-up can solve the global food crisis.”Mr. Tetrick decided to join the excitement. It was a good time for a new horizon: That year, Bloomberg ran a scathing investigation that found that Hampton Creek, now called Eat Just, had sent people out to buy up jars of its vegan mayonnaise to give the impression of higher consumer demand. (Eat Just says the program was in part for quality assurance purposes.) Bloomberg also reported that Mr. Tetrick had engaged in a romantic relationship with a subordinate, that Eat Just had wildly overestimated its sustainability impacts and that the company had been accused by a senior executive, the influential Silicon Valley angel investor Ali Partovi, of deceiving investors. In 2017, every board member except Mr. Tetrick resigned.

I visited Eat Just’s San Francisco headquarters in December of that year to taste a sample of Just Egg, the plant-based egg substitute that the company still sells. To my surprise, I was also shown sketches of what a cultivated meat factory might look like. I was told that someday a factory like that might even produce enough cultured protein to feed the entire United States — a fraction of the size of the average cattle ranch but so much more efficient. In just 15 days, a teardrop of cells would be grown into millions of pounds of meat. The book “Clean Meat” describes Mr. Tetrick looking at factory drawings and saying, “By 2025, we’ll build the first of these facilities,” and by 2030, “we’re the world’s largest meat company.”

Challenges were mounting, however. The company was exploring duck products like foie gras and duck chorizo when, sometime in 2018, scientists ran a scan on the cells being used — and found mouse cells. It wasn’t a result of poor hygiene; the contaminants originated from laboratory materials, not live vermin. But Eat Just had to scrap the whole cell line, and ended up scrapping the duck products altogether. The incident highlighted some of the many challenges of transitioning cell cultivation from academic research to commercial food production. The company recently told me that the contamination was an isolated incident, and “as soon as we realized a contamination did occur, we did not serve to anyone.”

Such setbacks did nothing to slow the pace of the industry’s growth. In the next year alone, at least 20 new cultured meat companies announced they were entering the already crowded fray. Bruce Friedrich, the president of the nonprofit Good Food Institute, shouted from the rooftops about all of the investment firms, tech accelerators and meat-industry incumbents getting in on the action, calling cultivated meats an “immense investment opportunity.” RethinkX, a think tank focused on the adoption of new technologies, went even further. “By 2030, demand for cow products will have fallen by 70 percent,” one of its white papers said. “Before we reach this point, the U.S. cattle industry will be effectively bankrupt.” It went on, “Other livestock markets such as chicken, pig, and fish will follow a similar trajectory.”

“We get the cost down and get the taste up, and I think very likely in the near future this is the meat,” Mr. Tetrick told the Good Food Institute’s annual convention. “And there’s very unlikely to be another option.”

George Peppou, C.E.O. of a then months-old Australian cultivated meat company, Vow, was there in the audience. “I remember sitting there thinking, wow, this is amazing,” he said. “These companies are ready. Like, this is happening.”

Something was happening, but what, exactly? In 2019, as all these companies worked to find viable paths to market, scientists working for the company that would later become Upside ran genetic tests on a high-performing chicken cell line. To their dismay they, too, found contamination with laboratory cells, but in this case it was a rodent even less palatable than mouse: rat.

In an email, Upside said that the contaminated cell line was never “intended for our commercial process or pipeline” and that this was an isolated incident that helped the company refine its quality control measures.

In January of 2020, the company announced it had raised $161 million in a funding round, the largest publicly disclosed investment for a company making cultivated meat.

Steve Molino is a principal at Clear Current Capital, an early-stage venture fund focused on sustainable food and an early backer of BlueNalu (cell-grown bluefin tuna, a reported $118.3 million raised). He’s no stranger to the practice of placing big bets with limited information, but even so, he was amazed to see the way money poured into the industry. “There were no real numbers to pull from that allowed anyone to say, ‘Wait a second, this is either going to not work — or, if it does work, take a really long time.’ Without that data,” he said, someone could give you a tiny sample of something, “And you’re like, ‘Holy crap, this is the future.’”

***

Josh Tetrick remembers being in Boulder, Colo., on Thanksgiving Day 2020, endlessly calling his team for updates from Singapore, where Eat Just was seeking its first government approval. “I lay down and I put my phone away for a while just to stop, like, incessantly checking,” he told me. “I fell asleep on the floor. And I woke up to our head of regulatory calling me and saying, ‘Josh, we got it.’”

Eat Just’s cultivated meat division had the capacity to produce only a small amount of chicken, and that at a steep financial loss. The process still relied on fetal bovine serum, a product of the brutal animal supply chain that cultured meat was supposed to make obsolete. The product, the company said, was about 30 percent plant-based ingredients, a cross between a chicken nugget and a veggie burger. Regardless, the approval was treated as a historic event. “No-kill, lab-grown meat to go on sale for first time,” The Guardian wrote, in a piece that called the development “a landmark moment across the meat industry.”

Investment in the industry increased by more than 300 percent between 2020 and 2021. Shiok Meats, which started as a cultivated seafood company, managed to raise a reported $30 million without even having a cell line that could grow sufficiently in culture, a basic requirement for success. New Age Eats, a company that made cultivated sausages that were only 1 percent to 2 percent animal cells, raised $32 million and began construction of a 23,000-square-foot manufacturing facility in Alameda, Calif. The factory was an example of what an article in the journal Nature Food would broadly refer to as the industry’s “Potemkin pilot facilities.”

Isha Datar, executive director of New Harvest, a nonprofit that funds public, academic research into cultivated meat, said she watched all this incredulously, knowing that fundamental scientific problems hadn’t been worked out. “This,” she remembered telling her board, “is a bubble that is going to pop.”

In November 2021, Upside opened its factory in Emeryville, Calif. “It’s not a dream anymore,” Mr. Valeti told an ecstatic throng of employees during a ribbon-cutting the company livestreamed on YouTube. The Emeryville facility had been designed with big gleaming reactors in part, the company said, to produce whole cut chicken breasts. As I recently reported with Matt Reynolds, however, Upside has been brewing its chicken cutlets almost by hand in minuscule quantities, using disposable plastic bottles — an unwieldy, unscalable and unsustainable process that seems to generate more plastic waste than meat. Upside recently told me that the chicken cutlet operation was never about scale: “Its intent — which it has accomplished — is to inspire consumers with a North Star of what is possible with cultivated meat.”

As for Eat Just, in May 2022, its cultivated meat division, Good Meat, announced plans to build two factories, in Singapore and the United States. The U.S. factory would be a mega-facility housing 10 250,000-liter bioreactors and able, Eat Just said at the time, to produce millions of pounds of meat. But projected costs spiraled, just as start-up funding skidded into a steep decline.

“I was surprised,” Mr. Tetrick told me, “how quickly the capital markets shut.” A major backer of cell meat companies, he said, told him he’d switched to investing in real estate.

Last year, ABEC, a construction company that was a key partner on the facilities, sued Eat Just and its cultivated meat division for about $100 million in unpaid bills and payments for changes to the scope of the work. (Counterclaims allege that, among other things, ABEC failed to deliver equipment that had been purchased.) Another company has also sued for millions in unpaid bills.

After all those years of exuberance — but still with no product available in any stores — the bill, it seemed, had finally come due.

***

When I visited Eat Just’s Alameda headquarters last month, I first spotted Josh Tetrick hunched inside a darkened, glass-walled conference room on a Zoom call, a complicated spreadsheet up on the projector screen. Eat Just laid off at least 80 employees in 2023, and during my visit the company was in a process of downsizing from two buildings into one.

The confident charm Mr. Tetrick used to exude is today more muted; he now exudes the willful stoicism of a fire walker, with occasional flashes of frustration and grief.

“The unfortunate outlook that I’m required to have is one that is very long term,” he told me. “You have to have a view of not just the next 10 years, but the next 50 years.” The purpose isn’t racing to build a huge factory, he added. “The purpose is doing things that increase the likelihood that over the course of decades — I’m gulping saying ‘decades,’” he said. “I’m choking on these words.”

Mr. Tetrick said he hoped Eat Just, which still sells plant-based products like Just Egg, will break even this year. But the man who once spoke so optimistically about the revolution told me, “I don’t know if we, the industry, will be able to figure it out in a way that we need to in our lifetime.” He managed a strained laugh. “Folks who invest in our company don’t want to be talking about lifetimes.”

The truth, Mr. Tetrick said, is that the economics of cultivated meat won’t work for anyone until factories can be built for a fraction of their current cost, and he doesn’t know how to solve that.

To describe the emotional force of that realization, Mr. Tetrick repeatedly paraphrased Mike Tyson’s line about how everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.

The same brutal blow may be waiting for other companies when they try to scale in earnest, he said. Most of them just don’t know it yet.

***

Mr. Tetrick’s competitor, Upside Foods, doesn’t have any products in stores either, but it said it’s still optimistic about its prospects. The company has “made significant progress” on new products and manufacturing processes and is now focused on developing ground cultivated chicken meat, which will be the initial focus of a planned 187,000-square-foot factory north of Chicago.

I tried several times to speak with Uma Valeti, Upside’s C.E.O., but his spokeswoman declined. In response to my detailed questions, the company responded, in part: “As with every transformative technology, our path and plan to scale have evolved as we have innovated and endeavored to do something that has never been done before, against the backdrop of an ever-changing and unpredictable external and economic environment. Innovation does not follow a straight and continuous line. The suggestion that our path is unusual ignores the reality of how transformative technologies develop and does a disservice to every innovator who dares to bring something new into the world.”

It’s true, of course, that innovation is rarely linear. Setbacks are to be expected in the development of any new technology. Progress, too — and there have been some recent advances.

Researchers at Tufts University have engineered cow cells to produce a protein that previously needed to be purchased at great expense. And Upside and Eat Just, among others, have figured out how to make their nutrient broth more cheaply while avoiding fetal bovine serum. Some industry observers say that incremental improvements like these could one day make luxury cultured meats feasible in higher-paying niche markets or could improve primarily plant-based offerings. It’s also possible that research will lead to breakthroughs in other fields. “I am convinced something positive will stem from it, but I am not sure it will be meat,” said Isabelle Decitre, the founder of ID Capital, a food-tech-focused investment firm. Still, some people view the industry as a rising threat. Florida and Arizona have recently introduced bills that would ban the sale of cell-cultivated meat. Other states may follow.

But as familiar as cultivated meat’s bumpy trajectory may be, one thing stands out: The industry, and in particular, its two biggest players, Upside Foods and Eat Just, built expensive facilities and pushed for government approval before they had overcome the most fundamental technological challenges.

At a cellular agriculture summit last month at Tufts, a biotech expert, Dave Humbird, said the industry had “wishcast” its way to market readiness, something he’s never seen work. His prediction for the future of cultivated meat: “R.&D. will go back into academia. And that’s probably a good thing.”

His extensive analysis in the peer-reviewed journal Biotechnology and Bioengineering found that the costs of production at cultivated meat facilities would “likely preclude the affordability of their products as food.”

Several of the industry veterans I spoke to were even more bearish. Joel Stone is a consultant who specializes in industrial biotechnology. I asked him how likely it was that within my lifetime even 10 percent of U.S. meat supply will be cultivated.

“If I was going to put odds on it, the odds would be zero,” he said, flatly.

During my recent visit to Eat Just’s offices, I finally got my chance to try the product. In the test kitchen, chefs brought out a single large hunk of cultivated chicken on a gleaming white plate. They cut it into six slices, plating four for me with mushrooms and broccolini on top of a lovely, lavender-colored purée, and kept two for themselves and my host, Eat Just’s communications director, Carrie Kabat. Getting to taste it was still a special occasion for them, it seemed. “This cost $10,000,” one of the chefs joked.

The chicken was flavorful, with a mild savory umami taste, but the experience was closer to eating tofu or seitan than chicken, which makes sense since it’s filled with plant protein. It would never satisfy a hard-core meat eater, which, after all, was the point. So what was all this effort for?

***

We are in the middle of a slow-motion global catastrophe. With every passing year, the destructive force of climate change gets more destabilizing, and the human harm to animals gets more extreme. But the societywide changes we’ll need to make to avert the worst outcomes are overwhelming, too. It’s so tempting to cling to recent memories of a less disordered past.

Cultivated meat was an embodiment of the wish that we can change everything without changing anything. We wouldn’t need to rethink our relationship to Big Macs and bacon. We could go on believing that the world would always be the way we’ve known it.

Cultivated meat was also a tantalizing spin on a deeply American fantasy: that we can buy our way to a better world. In a world where our favorite indulgences tend to come at someone else’s — or something else’s — expense, this was a product that reframed consumption as virtue. And for the investor class, it was confirmation that making money and doing good can really be the same thing.

Last, it was a manifestation of our faith in technology and in dreamers with a fancy prototype, a pitch deck and a good amount of natural charm.

With that framing, cultivated meat always seemed like a story about optimism. It was about the way people came together and solved big problems in the nick of time. It was about the infinite potential of human ingenuity, our ability to make the impossible possible.

But the more time I’ve spent around this industry, the more I’ve felt that the whole project is fundamentally rooted in despair, an acknowledgment that real change, political change, was impossible, so we might as well offer people a sparkly new product to buy.

To my surprise, Mr. Tetrick saw it similarly. “The reason we do cultivated meat has to do with a lot of, actually, pessimism I have about the ability for humans collectively to make that change,” he told me in a phone conversation. “I think the addiction to meat runs so deep in us.”

Later, when we spoke in person, I asked him how he thinks about the $3 billion that investors put into cultivated meat. Could that money have made the world a better place if directed elsewhere? Mr. Tetrick perched his hands on his knees to represent two runners. The runner on the right, he said, represented grass-roots activism, political advocacy, nutritional education, farm policy, fair labor practices, animal conservation. The runner on the left was cultivated meat. If he had $3 billion, he mused, which would be the better bet to bring about the kind of world he says he wants first?

He chose the first runner.

Briefly, it was like he was emerging from a yearslong dream. But before I could ask him how, then, he could keep leading the company, he answered my question for me. The thing is, he said, you’re less likely to find people to give the first runner $3 billion. Even if it’s a better strategy, that’s not how the world works.

“People are a lot more motivated to invest in something where they can get a return in something than they are to donate something,” he said. “I think that’s unfortunate, but I think that’s the reality of it.”

Forget our diets for a minute. What will it take to change that attitude? We think of technology as fast, and bottom-up change as slow. But the irony is that sometimes new technologies can’t take off without plenty of unglamorous, collaborative effort. Without new regulations and bold political action. Without difficult cultural conversations. Without actual and sometimes uncomfortable change.

This story was produced in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

Mr. Fassler is a journalist covering food and environmental issues who has reported on the lab-grown-meat industry for six years.

[Top image: Credit...F.C.]