Articles Menu

Feb. 14, 2024

Vancouver Coastal Health warned Tuesday that we’re not ready for extreme weather caused by climate change.

What “urgent” risks you face depend on where you live, with poorer and racialized neighbourhoods and communities at particular high risk, according to Dr. Patricia Daly, Vancouver Coastal Health’s chief medical health officer. VCH serves a region that includes Vancouver, Squamish, Whistler and the Sunshine Coast, as well as coastal areas farther north, such as Bella Bella and Bella Coola.

In a report released Tuesday, VCH analyzed how hazards such as wildfire smoke, droughts, heat, storms and flooding will affect our health and identified ways to mitigate future harms.

“The existential threat to our population is climate change,” Daly said.

A lot of the issues and solutions in the report may be familiar, like how planting trees can cool streets or how opening clean air shelters can offer relief from wildfire smoke.

Communities have already identified climate change adaptations to keep their citizens safe, Daly said, and institutional partners like public health need to step up and figure out ways to support those efforts. Public health can also pay attention to social determinants of health and try to address pre-existing disparities, she added.

Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by climate change because of the ongoing legacy of colonialism. The report calls on Vancouver Coastal Health to listen to Indigenous communities about climate-change-related issues, such as disruption to traditional food sources, and to support First Nations-led efforts to address them.

Speaking to reporters, medical health officer Dr. Michael Schwandt said a lot of work has been done to improve the region’s ability to respond to a heat event.

But Schwandt added he worries how the deepening of societal inequalities such as the housing crisis will affect people’s ability to stay safe during extreme weather.

“The 2021 heat dome is not expected in any given summer, but we need to be prepared for it in every given summer,” Schwandt said.

Craig Brown, senior scientist, climate change and health, for VCH says extreme weather events in rapid succession, like two heat waves a week apart or during a power outage, are what frighten him the most.

The report focused on “exactly what’s happening” in the communities covered by Vancouver Coastal Health, which include 1.2 million people and 14 First Nations, Daly said.

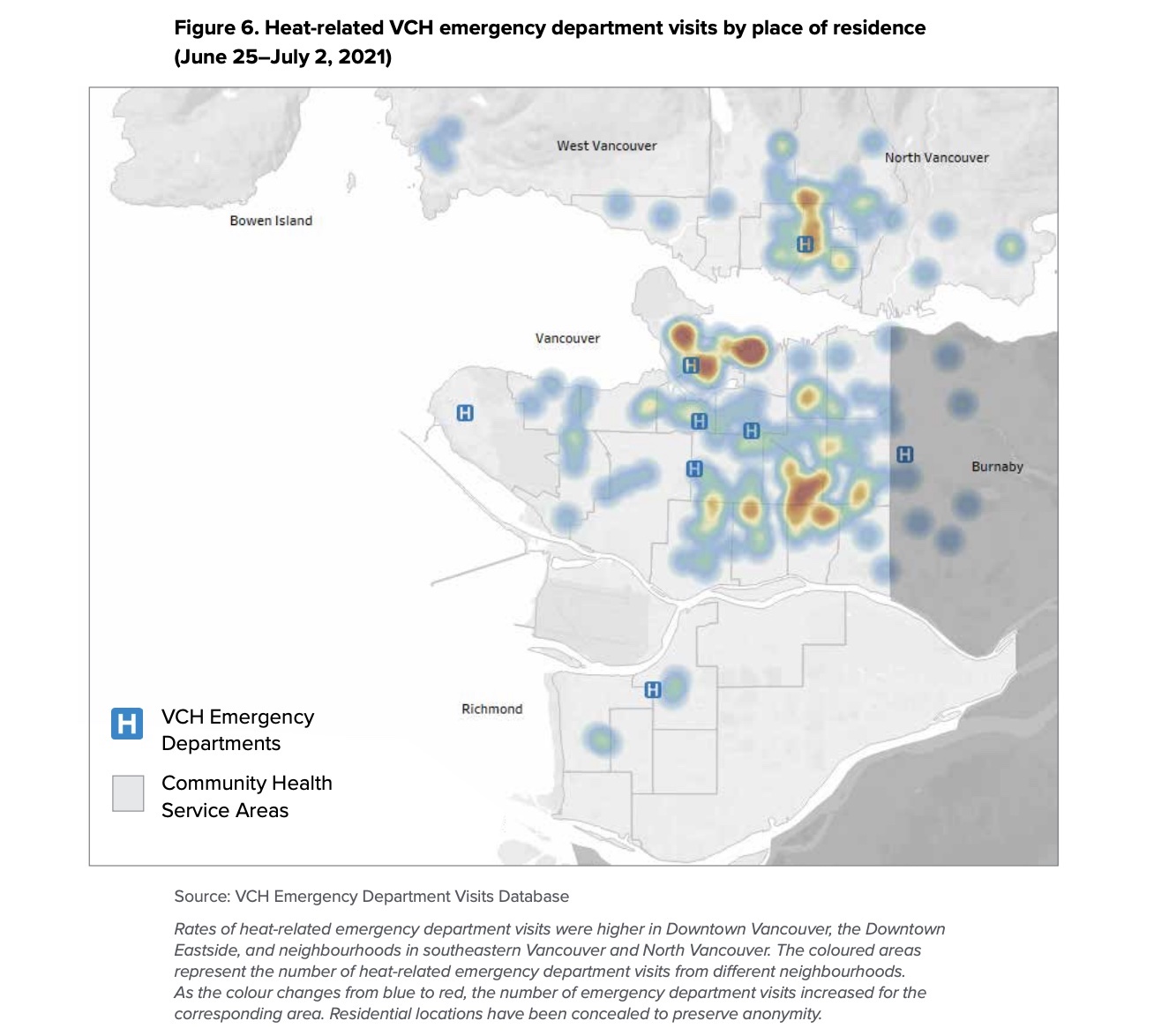

Researchers looked at information from ER departments to learn about deaths and mental health impacts. They also gathered data to provide insight into risks, for example including citizen scientist research where people reported temperatures inside their homes during heat events.

The report found 75 per cent of people without air conditioning in their homes had indoor temperatures of 26 C and higher, which is “very risky for people with susceptibilities to heat illness,” Schwandt said.

Many homes across Vancouver were hotter than 31 C, which is “known by experts on health and heat to be dangerous,” he added.

Trees and mechanical cooling: both necessary

Gabrielle Peters, a disabled writer and policy analyst, told The Tyee she was happy to see the report identify these temperatures but dismayed that it stopped short of making it a landlord’s responsibility to keep temperatures below 26 C.

“I’d be quite ill at 26 degrees Celsius. I think we can aim a little higher than creating living situations that you don’t die at,” she said. “But they don’t set temperature requirements at all.”

Peters was also critical of the wording in the report that “required” new buildings to have cooling systems but called for owners of existing buildings to “enable” mechanical cooling. It’s more expensive to rent in newer buildings, which means VCH is “building in inequitable access” to cooling, she said.

Peters said she wants to see B.C. set a date when all buildings are required to be retrofitted with mechanical cooling.

“At some point you make the decision that it needs to be standardized and you standardize it across the board,” she said. “I’m not sure how long it would have taken to get everyone heat if only new buildings had to have indoor heating — or plumbing.”

Schwandt said people living on the top floors of buildings, in units that have large, south-facing windows, are generally exposed to the highest temperatures.

Window shades, the number of trees and green spaces in a neighbourhood and air conditioning can help reduce temperatures and the danger they pose, he said.

Peters said it’s important to make sure trees and mechanical cooling systems don’t become an either-or issue. Trees can help cool a neighbourhood, but they won’t help someone living on the 15th storey of an apartment, she said.

The VCH map of 2021 heat dome emergency room visits makes this clear, Peters said. People living in the affluent downtown Vancouver neighbourhood, which has both trees and high towers, were strongly impacted by the extreme heat.

Mitigating the impacts of wildfire smoke

VCH’s Schwandt said people are being exposed to more wildfire smoke, “very directly driving health impact.”

“We need to mitigate and build more resilience to this.”

Clean air shelters have been shown to maintain healthy air during extreme smoke events, while indoor places without air purification can have air quality that is almost as bad as outdoors, he added.

Helping communities deploy air quality monitors could help people understand how safe the air in their neighbourhood is and plan accordingly.

Peters said she’d like to see more recognition that the impacts of climate change can happen concurrently. It’s not always possible for a disabled person to open windows and turn on a fan during a heat wave because the heat often comes with poor air quality, she said.

VCH’s report included 17 recommendations broken down into four main categories: how to protect vulnerable populations; how to adapt to climate change; ways to keep monitoring and learning about the health impacts of climate change; and how to mitigate further climate change.

It remains to be seen how government adopts the recommendations — but Schwandt warned not following them would “lead to colossal harms.”

“Interventions can be life-saving,” he added.

It could also save lives to make sure disabled people are included in all levels of planning and response, Peters said. She notes 91 per cent of the people who died during the 2021 heat dome were disabled.

“Disabled people make up the majority of deaths every single time because nobody has planned for our survival,” she said.

Michelle Gamage is The Tyee’s health reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative

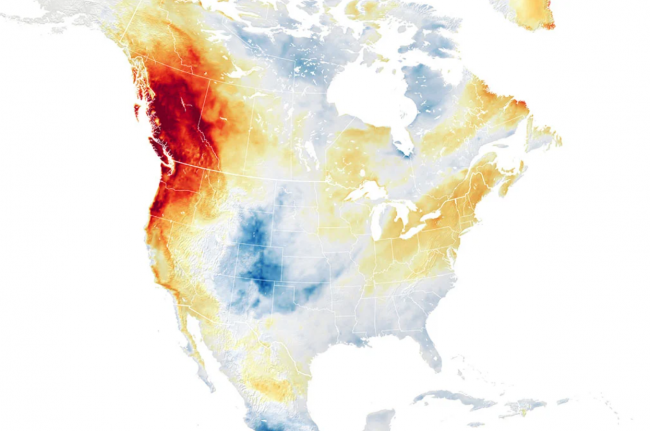

[Top: An image from the NASA Earth Observatory shows temperature anomalies across North America on June 27, 2021. Red areas show where air temperatures climbed more than 15 C higher than the 2014-20 average for the same day.]