When you think of “the year of protests,” what date comes to mind?

1968 saw massive global demonstrations about the Vietnam War, civil rights and many other social causes. At the end of 2019, the New Yorker noted “a tsunami of protests that swept across six continents and engulfed both liberal democracies and ruthless autocracies,” including major uprisings in Chile and Hong Kong. And the December 2022 edition of Time magazine proclaimed “the protester” to be the person of the year. Wikipedia conveniently lists all 104 protests that year, naming the countries alphabetically, as well as the issues.

As a lawyer with a particular focus of defending practitioners of civil disobedience because the act is vital to a healthy democracy, I appreciate and regularly visit the Global Protest Tracker, kept up to date by the U.S. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Scanning the United States, the European Union and Canada this year, it would not be a stretch to call 2025 the year of protests.

In the United States, the recent “No Kings” mobilization drew approximately five million protesters across the country and in every state. These outpourings also saw some remarkable new uses of technology. The app ICEBlock, for example, allows a user to share with other users, without revealing their own location, sightings of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement personnel within a five-mile radius of the user’s location.

This year in the European Union uprisings have abounded. Hundreds of Venetians protested in the streets and even swam in the canals to disrupt the wedding plans of Amazon tech tycoon Jeff Bezos.

In January and again in February of this year, tens of thousands demonstrated in Bratislava, Slovakia, protesting Prime Minister Robert Fico’s efforts to develop closer ties with Russia, in place of the European Union.

Also in early 2025, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a Donald Trump clone, oversaw the passage of legislation banning LGBTQ+ events countrywide. The new law clearly sought to suppress any outpouring of Pride by permitting the police to use facial recognition technology to identify participants. The force set about installing video cameras along the edge of the Pride parade route. But on June 26, 2025, a huge, colourful, musical protest jolted central Budapest, attended by LGBTQ+ activists and their supporters from across the continent.

Canadians have done their share to make 2025 the year of protest, including “No Tyrant” days of action in a number cities in support of the anti-Trump “No Kings” mobilizations in the United States.

Rallies against Elon Musk and Tesla products began in early 2025 in Vancouver and five other Canadian cities. The focus was Musk’s support for Trump and his statements about Canada becoming the 51st state.

Then we saw the “Hands Off” protests worldwide, including across Canada, in response to Trump’s trade war in April 2025.

Protests in “solidarity with Palestinian people” took place at many Canadian universities, including the University of Toronto, McMaster, McGill and Vancouver Island University.

And representatives of Treaty 9 First Nations burned documents in protest against Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s plan to kick-start mining by pushing through Bill 5 without any Indigenous consultation.

Sometimes protests focus on hyperlocal issues. Take, for example, the neighbourhood backlashes sparked by the City of Vancouver’s relocation of the brilliant Trans Am Totem, renamed Trans Am Rapture, a stack of crushed cars atop an old-growth cedar trunk, created by B.C. artists Marcus Bowcott and Helene Aspinall.

Sometimes protest takes a form different from folks clustered in public spaces. To press for electoral reform, more than 200 candidates have registered to be on the byelection ballot for the Battle River-Crowfoot riding where Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre is fighting to regain a seat in the House of Commons.

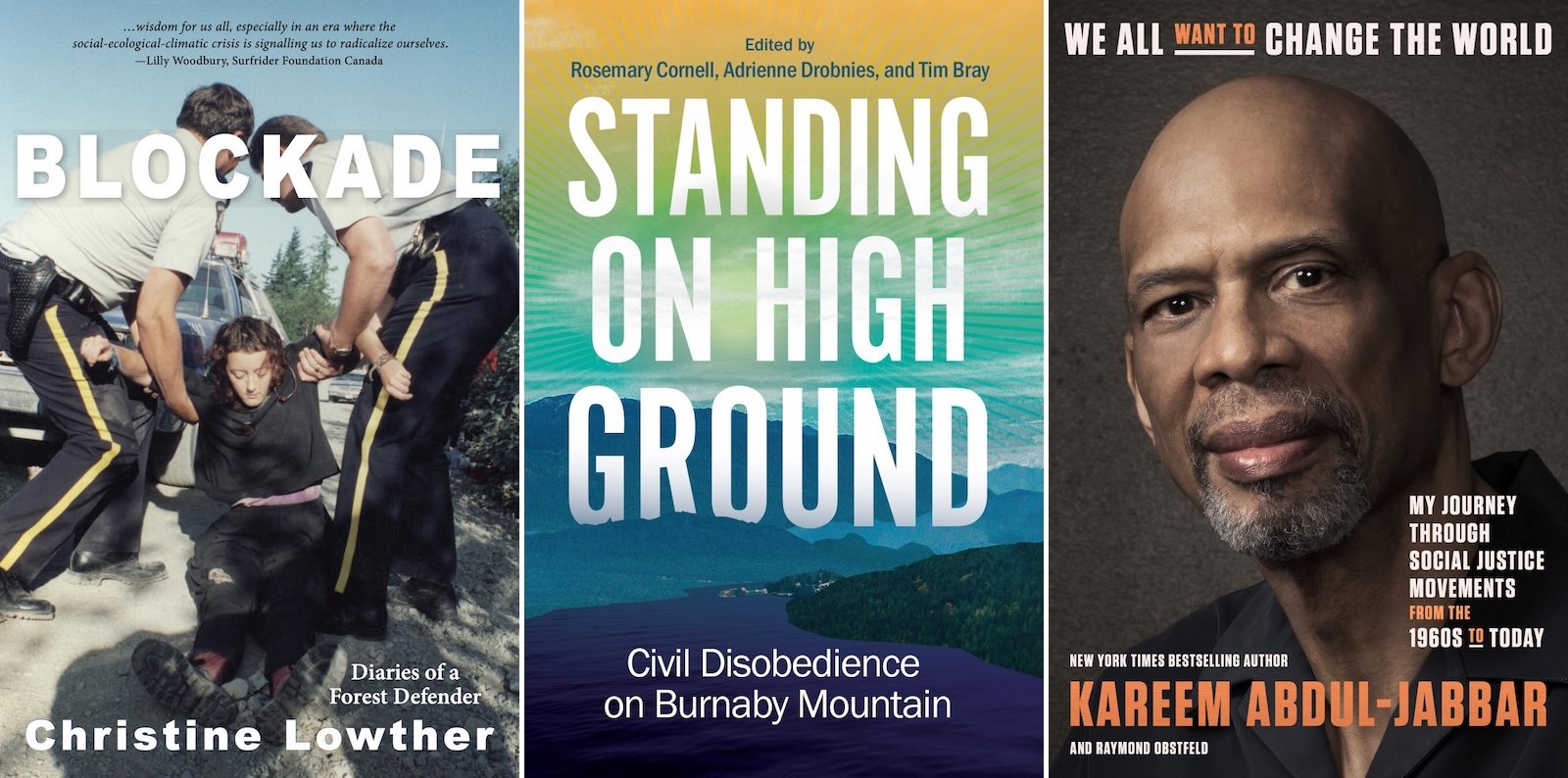

Given the political ferment of the moment, here are three books that provide interesting and helpful insights into the world of civil disobedience and protests.

Blockade: Diaries of a Forest Defender

Christine Lowther

Caitlin Press (2025)

The cover of Blockade shows two burly RCMP officers dragging the author, who offers no resistance, her face passive with a Pietà-like expression. The picture previews the story — a rich and compelling read of the life of a person determined to do whatever is possible to protect old-growth forests during B.C.’s epic “war in the woods,” which peaked in Clayoquot Sound in 1993.

Lowther’s language as a poet and a militant activist makes for a fascinating immersion. There are many passages in the book that provide advice for protesters, including the use of U-locks, the role of support people in the protests, the unique effectiveness of tree-sitting protests, and the use of air horns to warn protesters of the arrival of the RCMP.

Some of the most interesting passages recount exchanges between the arresting RCMP officers and the protesters. One involves an officer Lowther refers to as “the Tank.” Protesters he arrests simply for protesting, including a District of Tofino council member and a schoolteacher, tried to explain to the Tank that they had abided by the rules, all standing aside when they were asked to do so. The Tank ignored them. One tiny woman named Nicole, a foot shorter than the Tank, had no better luck. Lowther portrays the officer as a Sasquatch-sized bully mansplaining to a concerned mother that she was a threat and should mind her own business.

Lowther recounts: “Police walked into camp and arrested young people who continued to sing their hearts out even as they threw themselves in front of approaching company trucks. We were like hunted animals.”

Lowther’s description of the contempt-of-court hearings in Victoria in November 1991, including her written submission before her own sentencing, captures the harrowing stress and uncertainty surrounding these procedures.

Perhaps the most interesting chapter in Blockade is “The Summer We Got Big,” which describes how protests expanded through the summer of 1993. Thousands of people came to Clayoquot from around the world. Hundreds were arrested, with people spending weeks and months behind bars. As Lowther notes, important records of the time reside in Bob Bossin’s YouTube music video “Sulphur Passage,” Nettie Wild’s extraordinary documentary Fury for the Sound and, from the German state-owned public broadcaster, the 2024 film How Old-Growth Forests Protect Our Climate.

The blockade was at that time the largest in Canadian history, consisting of approximately 3,000 people on the road, many holding bright banners and placards. This was later followed by the “Great Clayoquot Sound Writers Reading and Literary Auction” at the Commodore on Granville Street in Vancouver. It’s described as the most prominent gathering of writers ever to assemble in the service of an environmental cause. The list of speakers, attendees and contributors included the who’s who of CanLit: Joy Kogawa, Al Purdy, Stan Persky, Lee Maracle, Patrick Lane, Lorna Crozier, Marilyn Bowering and many others.

Two other activists play an important part in the book. The first is Lowther’s mother, Patricia. She was a brilliant, trail-blazing feminist Canadian poet, brutally murdered at the age of 40 in September 1975.

The second activist, also mentioned many times in Blockade, is the environmental icon Ruth Masters, who had been protesting for over half a century before the Clayoquot clashes. Masters was responsible for most of the placards and banners used during the protests. She would also play “O Canada” on her harmonica during the arrests.

Masters as a protester was an early client of mine as a young lawyer, and she was the successful plaintiff in my first B.C. Supreme Court defamation trial: Masters v. Fox, 1978 CanLII 2057. The Courtenay and District Museum archives offer more on Masters’ amazing life and career.

The foreword to Blockade was written by Canadian author and poet Joy Kogawa, a friend of both Patricia and Christine Lowther. Kogawa says this about the book: “Chris takes us into the forest, into the magic and the songs of resistance and the moment-by-moment journey of those who care enough to live their hope. Pat would be enormously proud.”

Blockade ends with a valuable four-page bibliography of books, films and songs about the protests. It’s an excellent addition to the rapidly growing library on civil disobedience.

Standing on High Ground: Civil Disobedience on Burnaby Mountain

Edited by Rosemary Cornell, Adrienne Drobnies and Tim Bray

Between the Lines (2024)

This book consists of 25 first-hand stories of individuals who have been convicted of contempt of court — many sentenced to jail — for protesting the building of the Trans Mountain pipeline on Burnaby Mountain, a project that continues to be the subject of vigorous protests despite having been completed for some time.

The contempt sentencing and appeals of the protesters also continue, the most recent one being an appeal that was handed down just a few days ago: R. v. Cavanaugh, 2025 BCCA 252 (CanLII).

Those arrested include people with a long, admirable history of protest, and some who are new to it. They include Indigenous leaders, academics, religious leaders, political leaders, engineers, artists, writers, scientists, physicians and people from all walks of life.

One of the most notable is the account by George Rammell, a respected B.C. sculptor and art instructor. One of his best-known works is described and photographed in the book. Chambers of Predetermined Outcomes: Gatekeepers of Justice consists of three ventriloquist dummy judges shaking their heads and pounding their fists with their eyes reflecting the climate disasters captured on their laptops, all beneath a mock Canada coat of arms.

Poet and Emily Carr University of Art + Design associate professor Rita Wong contributes a detailed account of her experience along with her submission to the court. This is how she describes her time serving her sentence for engaging in civil disobedience:

“Prison was hard but bearable, and actually very educational for me. I noticed how people navigate a systematically violent structure by helping each other endure the system with compassion and kindness in all kinds of ways, big and small, notwithstanding personal and interpersonal dramas that come and go. In the spirit of sharing whatever gifts I could, I facilitated a creative writing workshop while I was in prison, for the women there have powerful voices, stories that need to be heard.”

Wong’s part of the book, incidentally, is partially adapted from an article published in The Tyee in 2019.

Robert Stowe, an MD, a neurologist and a member of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, was arrested as part of the protest. His address to the court is particularly compelling for the scientific data he includes on the environmental risks we face because of the building of the pipeline. His sister Barbara Stowe, a writer, was also arrested and charged. Their remarkable parents, Irving and Dorothy Stowe, were Quakers who came from Rhode Island during the Vietnam War and were instrumental in the startup of Greenpeace and the Georgia Straight newspaper.

We All Want to Change the World: My Journey Through Social Justice Movements from the 1960s to Today

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Raymond Obstfeld

Crown Publishing (2025)

I am always searching for books or articles on civil disobedience and protest to add to a vital list tallied by the Activist School. This new book was recommended to me by the folks at the wonderful Laughing Oyster Bookshop on Fifth Street in Courtenay, B.C.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was widely viewed as one of the best professional basketball players until his retirement in 1989. He has also been a lifelong social justice activist. The book is a rich, fascinating history of protests in the United States from the post-Second World War civil rights movement to the present. It covers the antiwar movement in the United States during its war on Vietnam, the women’s liberation movement and the gay rights movement, and closes with an assessment of the value of protests, along with some very valuable practical advice.

For readers who have been protesting or are planning to, I also recommend familiarizing yourself with the excellent BC Civil Liberties Association protest handbook, available online.

And for U.S.-based Tyee readers, I recommend the American Civil Liberties Union handbook, also available online.

The U.S. National Lawyers Guild also has excellent material online for protesters, and for observers.

And now a bit of lawyerly advice. Canadians have a remarkable history of joining American friends in protests over common issues. But given the arbitrary powers now held by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, protesting in the United States is unwise.

Leo McGrady is a longtime Vancouver lawyer, author and law teacher. He’s been The Tyee’s media law counsel since its founding.