Articles Menu

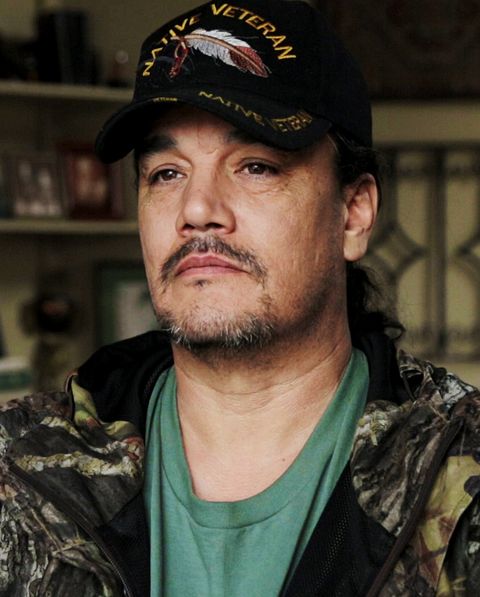

Rattler sat on the sofa scrolling through his phone. It was a drizzling, cold spring day in Bismarck, North Dakota, but he wasn’t going outside much anyway. A great mountain of a man with thick black hair to his waist and a disarming gentleness, Rattler made the objects around him look small. The sofa on which he sat, the phone he held, the homey living room where we met, the whole city of Bismarck seemed too small for Rattler. But his bail conditions and an ankle monitor confined him to the area for over half a year as he awaits trial.

He put the phone down. "I was looking for a quote," he said, "about how the people have the right to overthrow the government if it abuses its power. Who said that?"

Sandra Freeman, Rattler’s attorney, sat with him on the sofa. She ventured that the line he was seeking might be from the Declaration of Independence. Rattler didn’t return to his phone to check. If he had, he may have noticed that Jefferson’s founding document, that vaunted proclamation of America and its values, described the land’s native peoples, his ancestors, as “merciless Indian savages.”

Rattler, 45, legal name Michael Markus, is one of six native activists facing near-unprecedented federal charges related to the Standing Rock protest camps against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). The federal cases sit alongside hundreds and hundreds brought by state prosecutors, stemming from vast numbers of arrests made over the six months that the camps stood—a protest which at its height drew up to 15,000 participants from around the world and, for a short time, the dilettantish gaze of the mainstream media. The authorities razed the last major holdouts of the camps on February 23, by which point numbers had already dwindled as blizzard conditions pummeled the prairie lands. The camera crews packed up and most of the country went back to focusing on Trump.

But for Rattler, his federal co-defendants, the many hundreds of arrestees facing state charges, and their lawyers, the fight on the ground in North Dakota is far from over. They face a terrain as brutal and unforgiving as any winter on the Standing Rock reservation: a small-town court system in conservative rural counties with no experience of anything nearing this scale or political valence.

The fate of the DAPL standoff does not only reside in judicial decisions about the flow of oil. Those who stood on the frontlines for clean water, for indigenous struggle, for their ancestors and for our future, are being brought to alleged justice in an area where the very possibility of an impartial jury is in serious doubt. North Dakota prosecutor Ladd Erickson told me over the phone that prior to the Standing Rock cases, the only mass arrest incidents that these local counties had dealt with involved breaking up graduation parties of drunk high-schoolers. And while thousands flocked to the protest camps, only a few dozen lawyers and supporters remain and return to continue the arduous and overwhelming task of defending these cases in an area where towns consist of interconnected parking lots, strip mall restaurants and boxy houses, surrounded by unending sightlines of rolling grassland. At the time of writing, 140 defendants still don’t even have legal representation, according to figures from the WPLC.

“The reality is that the frontlines are in the courthouse now,” said Freeman, a former public defender who moved from Colorado to live in North Dakota full-time to fight the DAPL arrest cases. She is one among a small cadre of lawyers and legal support workers who have put their normal lives on hold in order to seek justice for water protectors facing trial in the conservative, rural midwest. “The celebration and camaraderie of the camp—that’s gone,” she said, “but we’re left to stand with people going into the gauntlet, facing incarceration for being who they are.”

The Dakota Access Pipeline is now fully built, following President Donald Trump's January order to expedite its completion, which reversed President Obama’s block on the project. In June, crude oil began pumping from North Dakota’s Bakken Formation to Illinois, under the Mississippi river and through sacred Lakota land and burial sites. There has already been one spill, albeit small. A major spill would contaminate the main water source of the Standing Rock Sioux and 17 million people who live downstream. Last month, a federal judge ruled that the Army Corps of Engineers, responsible for approving the pipeline’s route and completion, had not adequately considered the impacts of a spill into the Missouri River. The decision is a partial victory for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, but too little too late and oil is still flowing through the DAPL. Since February, anti-pipeline activists have taken their fight from North Dakota to new camps across the U.S., against pipeline construction and fracking operations in Nebraska, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Texas, Florida, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

On the first night I spoke to Freeman in the dingy apartment rented by her legal collective in Mandan—the small town in which most of the hundreds of state cases will be tried—she pulled out a dog-eared map of the area. On it were the lines of the Fort Laramie treaties, which drew up the Great Sioux Reservation in 1851 and 1868. And next to it, Freeman roughly sketched how the land today—the site of the pipeline standoff—is broken up into federal, private and reservation property. “The history of exploitation and extraction cannot be disconnected from what’s happening here,” she said.

The unbroken American history of native oppression is not lost on Rattler, a marine veteran, truck driver and card-carrying Oglala Lakota Sioux Indian who lives on the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota—designated one of the poorest areas in America. His great-great-great-great grandfather was Chief Red Cloud, the storied Oglala Lakota leader who oversaw successful campaigns against the U.S. Army in 1866 and signed the 1868 Fort Laramie treaty, delineating the Indian Country through which the DAPL now runs. Red Cloud died at Pine Ridge in 1909. The same Pine Ridge where over 250 Lakota were massacred and buried in a mass grave in 1890 at Wounded Knee; the same Wounded Knee where, in 1973, American Indian Movement (AIM) activists and supporters from every Indian nation occupied the town. Unlike the Standing Rock standoff, the Wounded Knee occupation was armed. But like the water protectors four decades later, the AIM resistance at Wounded Knee faced militarized, multi-agency law enforcement repression, followed by protracted court battles aimed at defanging and punishing the movement.

Native American protesters and their supporters are confronted by security during a demonstration against work being done for the Dakota Access Pipeline oil pipeline on September 3, 2016.

And it is with this historic struggle in mind that Freeman chose to join the camp, originally “supporting the DAPL resistance not in [her] capacity as an attorney.” She told me that after seeing water protectors “brutalized by police,” and recognizing the expansive need for legal support, she applied in November to work as the Criminal Case Coordinator for the Water Protector Legal Collective—a group that originated in the camp to provide on-the-ground jail and legal support for arrestees and is now one of two interconnected, donation-funded groups overseeing the daunting task of coordinating defense and logistics for hundreds of disparate defendants. The other, the Freshet Collective, works largely on arrestee support, such paying nearly a half a million dollars in cash bail, coordinating criminal defense, travel, accommodation, and logistics for the out-of-state lawyers and hundreds of defendants who live nowhere near the site of their court dates. Freeman moved to North Dakota, leaving her family and her regular legal practice in Denver for months at a time.

“For a lot of the lawyers and the defendants here, there’s a spirituality and a politics involved in this fight that can’t be untangled, and it would be hard to keep working without it. So much out here is hard,” Freeman said. “The attorneys and legal workers who come here, we wake up every morning and put our bodies and spirits upon the gears, upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus of this colonial behemoth—the state violence and repression that is occurring yet again in order to deny indigenous people sovereignty over their own lands in the name of resource extraction.”

The Standing Rock federal trials are not likely to begin until October, at the earliest. The six federal defendants have all been charged with use of fire to commit an offense and civil disorder, stemming from events on October 27—a major date in the pipeline standoff on which 141 people were arrested. Police deployed armored vehicles, lashes of pepper spray and LRAD sound cannons to clear water protectors from one of the campsites, while barricades were set alight and DAPL equipment was damaged. The civil disorder charge is a rarely used federal statute with a fiercely political history—it was passed in the late 1960s at the height of the Black Liberation and anti-war movements. AIM members from the Wounded Knee occupation faced the very same charge.

Protesters build a tipi at Oceti Sakowin Camp on the edge of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on December 2, 2016 outside Cannon Ball, North Dakota.

It was not until January 23, three days after Trump’s inauguration, that the Justice Department moved to file federal charges. This, Freeman said, was “no accident.” Each defendant now faces up to 15 years in prison if convicted.

Meanwhile the state cases are already trickling through Morton County, with hundreds still unresolved. “The size and scope of the thing, it’s overwhelming,” said Freeman.

It’s hard to imagine a starker visual disconnect between the dramatic spectacle of the protest camps and the boxy smalltown blocks and parking lot grids that make up the nearby cities. The pipeline fight provided a visual language of indigenous resistance and frontline militarized battle: the bright flags of every tribal nation flying, the temporary tent and tipi towns, hundreds of bold banners, water protectors in traditional dress on horses, law enforcement officers and National Guardsmen in riot gear. Tear gas. Water cannons. Fire.

Just over 70,000 people live in Bismarck, where the federal court is small enough to share a building with the post office, the granite stone entrance of which became a regular backdrop for protests. In bars decked in mock saloon style and American flags, “Backing the Blue: Friends of Law Enforcement” signs are posted in the windows. Neighboring Mandan has a mere 21,769 residents—slightly larger than the population of the protest camps at their largest. Mandan, named after the indigenous tribe that historically lived on that land, has a 90 percent white population and boasts the slogan “Where the West Begins.” If you squint, it could almost be quaint; a late 19th-century railroad town with morning-trimmed store fronts and saloons. But to look at it clearly is to see cheap, beige concrete facades and dilapidated motels, sports bars and chain restaurants. Here, the lawyers and legal support workers live and work out of a former hotel-turned-flophouse, with a makeshift office on the ground floor. Inside the main building entrance sits an old-timey buggy car—no doubt once an ornament from the hotel days. A Christmas wreath hangs on the wall in mid-Spring.

The curtains are drawn over the office windows and there are no signs on the door. They work in one large room with mismatched felt sofas and plastic chairs, a shit-brown carpet, a defunct popcorn machine, and a poster of Leonard Peltier pinned to the wall. According to Freeman and her colleagues, the first two buildings in which they tried to rent turned them down after hearing that they were in town to defend water protectors. “It’s hostile environment here, for sure,” Freeman said.

“THE SIZE AND SCOPE OF THE THING, IT’S OVERWHELMING."

Rattler told me in the previous weeks, on two occasions, two different unmarked cars pulled up beside him on the street and a passenger brandished a Glock 10 before the vehicles sped away. He said that numerous local residents have driven by and yelled, “Go home!” while he smoked on the porch. “It’s funny, because I want to get out of here, too,” he said. “But part of me wants to yell back, ‘Go home? We were here first!’” He’s staying at the home of a member of the local Unitarian Church, a small detached house near the center of Bismarck in a row of small detached houses, in organized, anonymous, suburban-looking blocks.

I came to North Dakota three months after the February eviction. There was all but no sign of the once sprawling camps that had stood 40 miles south of Bismarck. You have to look hard for relics left on the wind beaten, sand-brown grass, like a lone cinder block bearing “#NoDAPL” in black spray paint, or razor wire piled up in a mound by the 1806 Highway, gleaming in the sun. Riot police had used the wire to surround and block off a sacred burial site named Turtle Island after water protectors crossed near-freezing water to pray there in November.

I traveled to the site with Freeman and some of her co-workers. An ebullient paralegal named Jess in gold eye-shadow and a floral skirt pointed out where the various camp areas had stood. She hadn’t returned to the site since the February eviction. Nor had Dandilion Cloverdale, a sex worker and educator from Montana who now works for the Freshet Collective in North Dakota to coordinate travel and lodging for defendants. Cloverdale walked around solemnly, eyes streaming from the winds blowing sideways on the plains. “It’s sad coming back here, it looks so different” they said, adding “it’s hard,” a phrase I heard like a refrain that trip.

Cloverdale had been the camp manager for the small Two Spirit Nation camp at Standing Rock, which brought together the intersection of the indigenous and LBGTQ struggle and many Two Spirit youth. “Before the occupation there were two teen suicides a month on this reservation” said Cloverdale. “During the occupation, there were none. There was promise and hope, young people believed in themselves.” Native teens and young adults are 1.5 times as likely to kill themselves as the national average. The Standing Rock movement’s guiding words, Mni Wiconi (water is life) meant more than clean water advocacy. Water protectors and land defenders see themselves in a struggle to affirm and sustain life, which is as much spiritual as it is material and environmental.

Native American and other activists celebrate after learning an easement had been denied for the Dakota Access Pipeline at Oceti Sakowin Camp on the edge of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on December 4, 2016.

Not all the lawyers and organizers are in North Dakota full-time like Freeman; some come for a few weeks at a time for hearings and meetings—a semi-rotating cast of legal activists, who join the close quarters of the Mandan office and apartments. Most nights they cook and eat vegan food together, crammed into Freeman’s temporary living room on two sofas and the floor. Files and paperwork take up every table surface, with extension cords and wires from four to five laptops at a time snaking around the sparse furniture. Outside of their temporary lodgings, the Freshet and WPLC workers stand out in white Trump country; their ranks include Native Americans, gender nonconforming and queer individuals, trendy New Yorkers and what your grandparents might call hippies. “I was picking someone up from Bismarck airport,” Cloverdale told me, “and a group of white folks told me ‘you need to go home.’ They don’t like out-of-towners around here; they give dirty looks to out of state [license] plates.”

Freeman concurred. “I’ve never had to work as a defense attorney and endure this kind of hostile environment,” she said. A longtime activist lawyer, she noted that “unlike movements we’ve seen recently, there’s not a robust well of attorneys here. And the court system could have never anticipated this.”

The state Supreme Court deemed the situation an “emergency affecting the legal system of North Dakota.” Seventy defense lawyers from all over the state have been appointed to cases; “typically they live and work about four hours away,” Freeman said. But only about ten local defense council are working directly with the WPLC. With only so many barred criminal defense attorneys in North Dakota, a number of whom expressed negative bias against water protectors, the state has had to change its rules to let out-of-state lawyers practice in the Standing Rock cases in what’s known as a pro hac vice capacity. Pro hac vice lawyers must work with a barred North Dakota counsel—the local lawyers working with the WPLC are currently serving as local counsel for around 40 to 45 out-of-state lawyers.

North Dakota as a whole has an entrenched conservative bent with Republicans in firm control of the state house and executive. Local landowners and residents in the surrounding rural areas described the camps as a source of disruption, crime and vandalism.

“These were situations and circumstances we’d never seen before. It was emotionally, physically and economically taxing to the community,” said Julie Ellingson, the executive vice president of the North Dakota Stockmen’s association, a trade organization which represents livestock producers. “This is a quiet, agricultural area; the largest cattle producing county in the state,” said Ellingson, who has lived in the area all her life. She told me that during the time of the camps, livestock producers couldn’t move their cattle from field to field, faced protest-related roadblocks, and an alleged uptick in stolen, injured and killed animals.

Protesters stand their ground on the bridge between Oceti Sakowin Camp and County Road 134 in North Dakota on Sunday, Nov. 20, 2016 while being sprayed with water cannons.

On top of a uniquely brutal winter, these were unwelcome interruptions, which provoked ire against protesters, but not the pipeline that drew them to North Dakota. Ellingson was one among a number of local residents who told me that they believed the pipeline construction abided by relevant laws, regulations and necessary agreements—a view challenged by the (equally local) Standing Rock Sioux and their recent federal court victory over the lack of adequate environmental studies and adherence to treaty protections.

"THEY DON’T LIKE OUT-OF-TOWNERS AROUND HERE; THEY GIVE DIRTY LOOKS TO OUT OF STATE [LICENSE] PLATES.”

Ellingson said that locals felt like “collateral damage” in the Standing Rock standoff, a view echoed by Jerry Hintz, who owns a popular local tea shop and cafe with his wife in Bismarck. “Nobody in the media came to talk to the locals. They didn’t hear about how our businesses were affected, or about how police officers and their families were threatened,” said Hintz, who had joined hundreds of North Dakotans taken in a “Backing to Blue” rally last November and told me of “fierce loyalty” in the area to law enforcement and the military.

I met Hintz, a friendly, athletic 46-year-old with a shaved head and bright blue eyes, in his well-lit shop just a short walk from the federal court-cum-post office. The gray day poured in through the store’s glass front, deadening any touches of coziness in the strip mall space, which shares a bland Bismarck block with a Burger King. Hintz spoke of “agitators”, “trolls,” and “criminals” from the camps; “we wanted to be left alone,” he said.

Local fear and antipathy was further stoked through the concerted efforts of law enforcement officers, county authorities and mercenary security contractors (hired by DAPL owner Energy Transfer Partners) who spent months painting the water protectors as criminals and security threats. The Intercept’s TigerSwan leaks confirm that the private contractors, working with law enforcement agencies, carried out explicit propaganda campaigns in local and social media to demonize the protesters.

Despite blizzard conditions, military veterans march in support of the "water protectors" at Oceti Sakowin Camp on the edge of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on December 5, 2016 .

It worked. A survey conducted by consulting firm The National Jury Project in the relevant counties—Morton and Burleigh—found that 77 percent of the jury-eligible population in the former, which covers Mandan, and 85 percent of the latter, which covers Bismarck, had already decided the water protectors were guilty. “A substantial number of the surveyed population have connections to law enforcement, the oil industry, landowners and others who have been affected by the protests,” the survey results stated, noting, “Many respondents made statements indicating that they perceive protesters as a threat to community safety and described the water protectors as ‘eco terrorists,’ ‘criminals,’ and ‘idiots’ who ‘hopefully all freeze to death.’” One hundred percent of respondents admitted prior knowledge of the issues involved in the cases. Motions have been filed by attorneys in both state and federal court for a change of venue, to move the cases out of rural areas directly affected by the camps; at the time of writing, none have been granted and concerns about the very possibility of fair trials runs high.

For Freeman, the jury survey is a reflection of the sort of hostility she and clients and colleagues have felt in the area. “It’s also why we are trying to have Rattler’s bail conditions relaxed as soon as possible,” she said. "This is a threatening environment.”

US veterans and native americans hold hands in prayer and solidarity on the road near Oceti Sakowin Camp on the edge of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on December 4, 2016.

(In the first week of September, after months of filing motions and waiting, Freeman received the news from the Court that Rattler’s bond conditions would be relaxed to allow him to leave Bismarck to live somewhere else—somewhere approved by the court—while awaiting trial. Out of concern for his safety, Freeman does not want to make details of his next location public.)

Erickson, the state’s attorney known for theatrical language in court and chain smoking outside of it, told me that “the fatigue the whole area felt, it got raw.” A striking admission from a prosecutor about the risk of local bias. If the whole area was affected, I asked, how could impartial jurors be found for all these cases? “It’s challenging,” he admitted, before asserting swiftly that fair juries were nonetheless being found. He stressed that, contrary to charges of racism in the area against Indians, his Native American friends (“my guys” as he called them) in the sheriff’s department were also burned out by the camps. The same state’s attorney filed motions in December to disallow defendants from mentioning the following in court: “historical treaties between the U.S. Government and the Sioux Nation; tribal sovereignty; the merits and demerits of the Dakota Access Pipeline; climate change; sacred sites.” Erickson argued these issues had “no relevance” to the criminal cases at hand.

If an individual defendant did want to raise the fact that 99 percent of the arrests took place on land accorded to the Lakota tribe in either the 1851 or 1858 Fort Laramie treaties, the point would have little legal traction. But if these treaties—harsh compromises in and of themselves—were truly respected, none of these trials would be happening: state and federal powers have no jurisdiction on treaty land. If they had been historically respected, they would be no DAPL in the first place. The grim irony that many of the arrests led to trespass charges for natives on what should be their land is one that animates the history of this country.

Snow covers Oceti Sakowin Camp near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation on November 30, 2016.

The attorney noted that there is hardly anywhere to bring an argument from a sovereign nation’s claim—international courts are not going to weigh in on the Standing Rock criminal trials. But according to the lawyers I spoke to, including Bruce Ellison, a veteran attorney who represented AIM leaders after the 1973 standoff and continues to represent Leonard Peltier as well as a number of Standing Rock defendants, many of the cases are eminently defensible on points of law and proof, regardless of a treaty defense. The challenge is to defend what they believe to be defensible in this tough rural context with only a small legal operation handling hundreds of cases.

After a group dinner in her living room one night, Freeman and I sat in her equally jumbled adjoining bedroom. “In these cases we have both law and proof on our side. But really,” she said, with a quiver to her voice, “it’s the righteousness of it.”

In early July, Freshet published a tally of case statistics. Six hundred and four state cases were unresolved (517 open cases, 85 warrants issued and two cases going through appeal), with charges ranging from minor disorderly conduct violations to felony arson and assault on an officer. One hundred and fourteen people have already taken plea deals instead of traveling back to Bismarck—no small journey for activists coming from all around the country to face the possible risk of an unsympathetic jury. There had been eight convictions and three not-guilty rulings; the courts will take well over a year to get through the caseload. But by early August, prosecutors, lacking witnesses, evidence, and appropriate paperwork by arresting officers, began to dismiss cases by the dozen, often at the eleventh hour as court dates approach, but hundreds remain.

“IN THESE CASES WE HAVE BOTH LAW AND PROOF ON OUR SIDE. BUT REALLY,” SHE SAID, WITH A QUIVER TO HER VOICE, “IT’S THE RIGHTEOUSNESS OF IT.”

Accounting for every arrestee and finding each defendant appropriate representation has been a mammoth task in and of itself, and one that is not yet complete. In the meantime, Freshet and WPLC are working with the local lawyers and building collective defense strategies around major days of mass arrests—like October 27—from which scores of protesters face similar charges, while allegations of infirm arrest and police brutality are high.

And for the prosecutors, mass arrest days, which involved law enforcement officers from around the country and state, are proving a challenge. At the time of writing, over 168 charges have been outright dismissed by prosecutors before even attempting to extract pleas or go to trial, evidencing the illegitimacy of these charges in the first place. “The prosecution is realizing that they can't make out the elements of the charged offenses,” said Moira Meltzer-Cohen, a New-York based attorney who travels back and forth to North Dakota to represent nine defendants with cases in state court in Mandan. “Some of their cases have been dismissed by judges, and also because, having brought in law enforcement from all over the country, those extra-jurisdictional cops made arrests, failed to complete any meaningful paperwork, went home, and are not keen to return to testify about something that happened in a chaotic environment months ago,” she said, noting that without evidence showing individualized probable cause and without witnesses, the prosecution has been dismissing charges, which should have never been brought. Meltzer-Cohen, whom I’ve known for many years through her work on activist cases in New York, called the legal situation “a mess.”

US Navy deep sea diving veteran Rob McHaney holds an American flag as he leads a group of veteran activists back from a police barricade on a bridge near Oceti Sakowin Camp on December 4, 2016.

The fact that numerous cases have already been dismissed, and juries have delivered not-guilty verdicts in three cases already, including those of Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault and Tribal Councilman Dana Yellow Fat gives hope to the defense attorneys. Local paper, the Bismarck Tribune, which skewed dramatically against protesters and in favor of law enforcement in its editorial pages took the acquittals as an occasion to opine that “the system works for everyone.” Meltzer-Cohen scoffed at the editorial. “They had to acquit,” she said, “there was absolutely no basis for the charges.”

The lawyer does not see the recent wave of dismissals as an outright victory, but evidence of vast police misconduct and original prosecutorial overreach. “The way the cops use arrest as a form of crowd control dovetails so neatly with the way prosecutors drain us, even without getting any results. It's such a stupid war of attrition, with such pyrrhic victories on both ends,” she said. And for hundreds of arrestees, particularly the federal defendants, a reprieve is not on the near horizon.

Freeman believes that in the many cases that remain, only 10 percent of defendants will seek to settle out of court, but that the majority of water protectors will want to fight their cases. “I will go to trial, I will not take a plea,” said a 21-year-old named White Wolf, who faces state charges of riot and trespass from an October 22 arrest. White Wolf was born and raised in Louisiana and comes from the Houma tribe. She went to Standing Rock “because she had to. For the next generation. I went because my ancestors would have done it,” she said via phone. She was among the injured of November 20, shot squarely in the body by a police concussion grenade—a traumatic event from which she said she is still “healing.”

During the camp protests, the pipeline was dubbed “the black snake.” But for the Lakota, the black snake is not just one pipeline. It harkens back to a prophecy in which a great black snake would come to the Lakota lands and devastate the earth. According to the prophecy, it would be the youth who would rise up to slay the black snake—a detail not lost on the Standing Rock Sioux youth who were the first to set up camp against the pipeline in April 2016.

“The black snake is greed and violence and oppression; we have to come together to fight more than just one pipeline to defeat the black snake,” said Rattler as we sat in the warm, wood-accented living room. Depending on one’s spiritual orientation, there could be either irony or destiny in the fact of Rattler’s position as a high profile defendant in the Standing Rock trials. He earned his name during his marine corps service in the early ‘90s. One night, he was sleeping outside at bootcamp in Pendleton, California—diamondback rattlesnake territory—when he felt a weight along the side of his body. He carefully felt along the mass. A six-foot long poisonous diamondback had wedged itself head down along the side of his sleeping bag. In one move, Rattler grabbed his service knife, grabbed the snake, and cut off its head. His lieutenant, emerging from a tent, watched on. He retells the story with gusto, a grin and dramatic hand gestures. “I was known for pissing off dangerous snakes,” he said. The name Rattler stuck, now an appropriate nom-de-guerre for a man who came to North Dakota to fight the black snake, and whose liberty is under threat because of it.

Back in South Dakota, Rattler worked as a truck driver and a handyman, preferring to barter his trades and skills for items he needed to live, rather than money. Ceremony was already part of his life, as an entrusted Lakota pipe carrier—an honored role in ceremonial practice and tradition. He had first come to Standing Rock to deliver donated supplies from Pine Ridge in Betty Boop (his truck, for which he uses bio-fuel whenever possible). He made three return trips until one event in September prompted him to stay for good.

Campers set structures on fire in preparation of the Army Corp’s 2pm deadline to leave the Oceti Sakowin protest camp on February 22, 2017

“The dog attacks,” he said. In early September, protesters claimed that private DAPL security guards released attack dogs and sprayed mace on protesters. A spokesperson for Energy Transfer Partners told press at the time that protesters had "attacked" its workers first, but footage of clashes between law enforcement and water protectors catalyzed national attention. “After the dog attacks I knew I had to stay, it’s in my nature to want to protect people,” Rattler said. Freeman nodded as she listened to him, a hand on his shoulder. In that sense, they both had stayed in North Dakota for the very same reason—as protectors.

During his months stuck in Bismarck, the water protector has been waiting and praying. Most days, he stays inside, reads, writes and sketches. Rattler re-reads letters of support and solidarity he received from supporters around the country while he was in jail. “I even got some postcards from a woman in France,” he said, leaping up to pull from a cabinet a pile of assorted, well-handled cards and papers. He’s also working on a children’s book, he told me, a story about a young indigenous boy and his adventures in pre-colonial times. He wants to give children “an image of what we looked like, before Hollywood made us look like savages.”

“I’m not smart about a lot of things. I’m more of an action guy. But I have 100 percent trust in them,” he said turning to Freeman and wrapping her in a vast hug. “My life is in their hands,” he said. When we returned to her apartment above the office that night, Freeman briefly burst into tears, wiped her eyes, and got back to work.