Articles Menu

April 26, 2018 - It’s a good bet few business journalists currently working in Canada would recognize the name Ida Tarbell. Her reportage first appeared in 1902, in an American literary magazine called McClure’s. But she delivered a bombshell-opening salvo, in what became serialized as a 19-part investigative tour de force.

Each installment struck with concussive impact. They featured dense, unassailable details and a taciturn aversion to adjectives. Subscriptions soared. Her reports were compiled into a book, which became one the most acclaimed and best-selling non- fiction books of the early 20th Century.

Tarbell’s target was America’s biggest petroleum conglomerate, Standard Oil. She exposed, installment by installment, the brutally ruthless tactics (including serial Congressional bribery) the corporate colossus used to gain and maintain monopolies for shareholders and its galvanic founder, John D. Rockefeller. It enlightened the public, humbled the high and mighty, and ushered in a ‘trust-busting’ progressive U.S. President who ramrodded federal anti-monopoly laws through a simultaneously amazed, apoplectic Congress. Standard Oil and the Rockefellers never saw Tarbell, a former schoolteacher, coming. No one had dared to ask the questions she did, let alone print them.

Soon, fellow ‘muckraker’ reports exposed corruption and monopoly abuses in Chicago meatpacking plants, rapacious railroad barons, municipal graft, labour safety violations and union-busting, and appalling conditions in public insane asylums. One investigative report revealed that the owner of the worst slum tenements in New York City was the richest church in America.

The best of these journalists used an alloy of evidence and audacity. They dared to ask questions others were too lazy, inept or timid to ask. Our profession has its heroes – like Emile Zola accurately accusing the French government and military of knowingly convicting an innocent officer of treason. Or Woodward and Bernstein daring to ask if a troupe of third-rate, bungling burglars might be henchmen for President Richard Nixon. Or, more recently, Michael Lewis exposing breath-taking ‘big shorts’, rogue hedge funds and algorithm flash trading.

But a history of business journalism proves these figures are an exception. It is notorious for failing to detect bubbles before they burst with calamitous consequences.

The 1637 Dutch Tulip Bulb mania, the 1920 Ponzi postal fraud scheme, the 2001 Enron phantom-trading scam, Bernie Madoff’s criminal syndicate, and the 2008 U.S. mortgage fraud that rocked companies and economies across the globe, were all ripe for exposure long before they collapsed.

In Canada, our business press only belatedly dug up the real dirt on companies like Henry Pellatt’s Home Bank after its 1923 collapse, Viola Macmillan’s 1964 Windfall mining scam, the fatal coal methane levels at Clifford Frame’s Westray mine, the $6 billion Bre-X swindle (which was exposed after the chief prospector jumped from a helicoptor with false, salted samples) and the collapse of apparently venerable Nortel Networks in 2009.

In fact, the leading figures behind these spectacular failures were often lauded by the business press right up to the moment they became disgraced. The evidence of imminent demise was lurking, but nobody went looking for it. None dared ask tough questions. They did not do their job.

All this might be ancient history, but bubbles have a relentless way of appearing, garnering velocity, and growing exponentially bigger as more and more participants become invested for financial, employment and political reasons. At some point, they no longer dare ask if imported tulips, postage stamp values, Indonesian jungle drill-core samples, mortgage-backed security swaps or bitcoins have real value. They are in too deep.

Business journalists should know better, and be able to detect telltale signs. To avoid being true believers, most abide by professional protocols against owning stock or having any personal interest in ventures they might report on. That is an obvious conflict of interest.

However, they are not immune to the inducements of orthodoxy. Everyone loves a bubble (until they don’t), and those journalists who go out with pokers to test their surface strength are not held in high esteem by newsroom bosses, some readers and viewers, investors, companies pitching their products, or politicians who have hitched their wagon to making that bubble get bigger. It is easier to write see-no-evil testimonials, which all the inside players relish and court. Such coverage begets more coverage.

But bubbles are not endowed with immortality. They are, as a matter of physics, designed to fail. And the job of journalists is not to be popular, or go along to get along, but to pursue facts that matter – then let them fall ‘without fear or favour’.

Which brings us to Canada’s bitumen bubble, and missing-in-action media coverage, which amounts to malpractice.

In the days following Kinder Morgan’s ultimatum that it would jettison its planned Trans Mountain oil pipeline and forsake Canada unless it gains a clear and certain path to final approvals by May 31, a collective wail of lamentations ensued from oil companies, the pipeline manufacturers, the Alberta premier and Opposition leader, the Prime Minister and his senior cabinet members, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, and major banks. This is natural and fitting, and so is media coverage of their collective fury and resolve to avert that ultimatum. It is a big story. It needs to be covered.

However, it is not the media’s job to assume that opinions without evidence are equal in worth to opinions which are fact-based. Or to assume that the scale and decibel level coming from oilsands advocates is proof of their cause. A noise meter is not evidence. Or to assume that the voices of opposition should be discounted as, at best, merely emotional and at worst, severely irrational.

In a recent three-part series of investigative reports published by The Energy Mix, I laid out an evidence-based argument that there is no credible business case to support an expansion of oil sand exports or the proposed Trans Mountain and Keystone XL pipelines. That Alberta’s bitumen bubble is about to burst, due to multiple global forces far beyond its control.

This is either true, or it isn’t. Any business journalist is free to read these reports, assess the evidence presented and make up their own mind. Those who decline because they are already certain such a bitumen bubble does not exist, or believe that merely asking such a question amounts to heresy, or puts the “national interest” on trial, prove they are not an Ida Tarbell or Bob Woodward willing to dare, dig in and do their job.

If there is no credible business case for expanding bitumen exports (no Asian customers willing to buy huge volumes of Alberta oil at prices significantly higher than U.S. refiners will pay), then there is no business case for the Trans Mountain and Keystone XL pipelines. So no new investment capital for oilsands production or pipeline projects will be put at risk and existing oilsands producers will continue to operate at current scale. That will mean no extra royalty revenues for Alberta’s debt-plagued government to promise before an election next year and no victories for the federal Liberals to tout in 2019.

None of this is good for those inside the bitumen bubble. It means a world of hurt is on the horizon and that is something no oilsands opponents should celebrate. However, if there are no confirmed new Asian buyers lined up to buy Alberta bitumen for decades to come, then reality will hit home sooner or later. And the longer oilsands advocates pretend there is no bubble, the more brutal the impact will be.

In my view, Canada’s mainstream business news platforms (with a few stellar exceptions) have failed in their responsibility to make facts and evidence the cornerstone of their oilsands coverage. I routinely read the business sections of the Globe, Toronto Star, Edmonton Journal, Calgary Herald,Vancouver Sun, National Post and Financial Post. I scan BNN daily and the political panel shows of CBC and CTV.

To my knowledge, no one has asked these four key questions:

Tellingly, the working assumption seems to be that such business case certainty must exist, even though there is no evidence of it. That there isn’t a bitumen bubble, because no reporters have dared to ask if Alberta’s oilsands ambitions really amount to a bright and shining lie. Just as generations of children don’t press their parents very hard about that pony they expect to get for Christmas and how it will get down the chimney. The answer might be unthinkable.

But this media malpractice is not just a sin of omission, of failing to ask tough questions. It is a sin of commission when business journalists or media personalities lob only softball questions to oilsands advocates. They print or broadcast assumptions masking as facts, and confuse what many Albertans would like to happen with what is likely to happen because of inconvenient facts.

As journalists, we do Canadian citizens, readers and viewers, no favours by evading uncomfortable evidence, ignoring basic failures of logic, or not exposing glaring contradictions and concealed conflicts of interest. Otherwise, we are enablers – not an instrument of democratic and social accountability.

Some examples: In a month of media coverage about the escalating battle about the Kinder Morgan pipeline, not once have I seen a climate scientist interviewed about the risk greatly expanded bitumen exports might pose to people and the biosphere. In effect, science (the most reliable source of facts) has been banished from the debate stage, leaving provincial economics and national politics to dominate every discussion. How convenient.

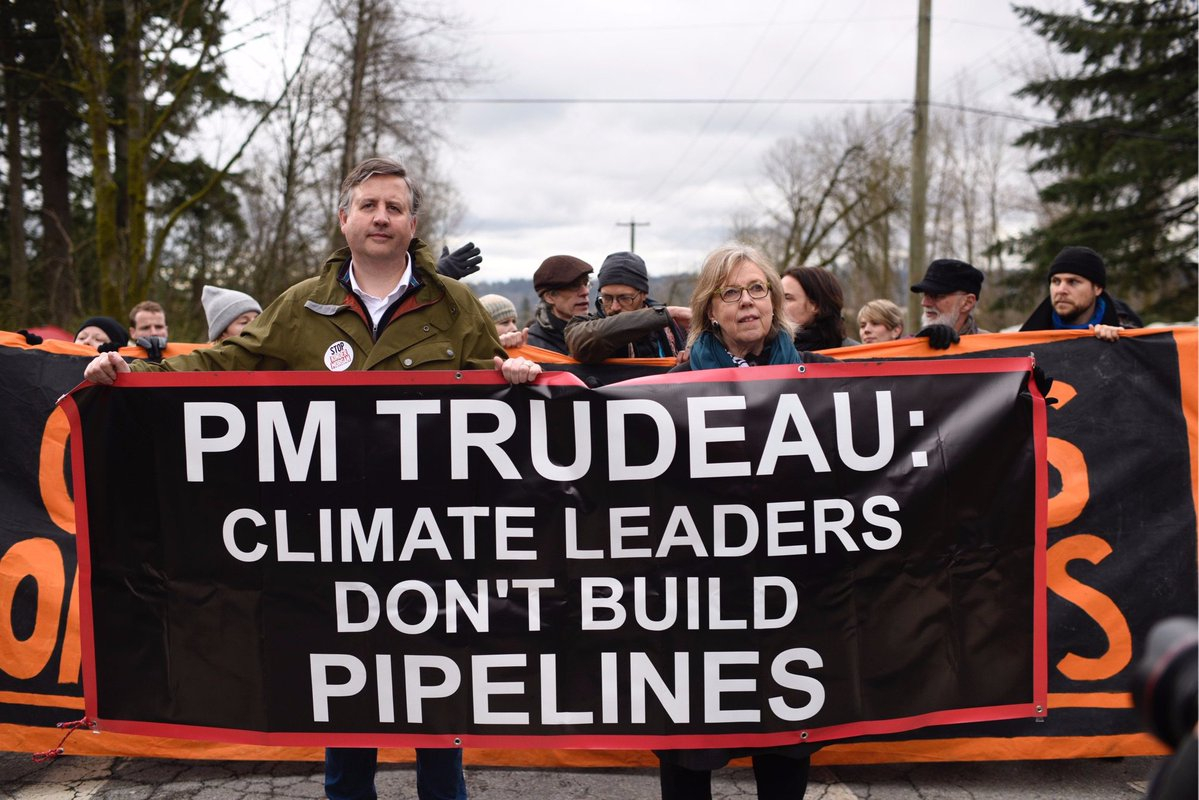

This has partitioned the parameters of debate, and the very vocabulary used. The fate of Alberta future oilsands and pipeline projects gets confronted not by respected climate or marine scientists, but video clips of Left-Coast environmentalists with a placard in one hand and a latte in the other. Bitumen with a demonstrably deadly chemical signature becomes a benign ‘product’ or ‘resource,’ barely different from wheat, lumber or potash.

Yet the world’s top climate scientists have explicitly warned that Alberta’s oilsands amount to a delayed-fuse ‘carbon bomb’ our biosphere cannot tolerate. Top international economists, led by the esteemed and astute Lord Nicholas Stern, have identified those same bitumen deposits as ‘unburnable’ stranded assets. To date, these scientists and economists have not issued warnings about the perils of Canadian potash exports.

Once adopted, these unchallenged oilsands euphemisms take on a force of their own and foster new imperatives. Of course, Albertans should be outraged if they can’t get their ‘resource’ to market. Of course the federal government should step in to protect the sanctity of equitable, inter-provincial trade. Ergo, the Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion becomes a matter of national interest, where supporters are patriots, opponents are almost treasonous and any province which defers approvals until more science is completed is worthy only of being ‘nation-shamed.'

From that it was a lightning-quick leap for some corporate leaders to publicly lament that the Trans Mountain stand-off means that all infrastructure investment in Canada is ready to fall off a fiscal cliff, that soon foreign financiers will only touch us with a pole longer than the CN Tower, and that our resource sector may never recover from such a body blow to our global reputation. Many of these comments were recycled into next-day business stories and approvingly quoted by an emboldened Alberta premier and senior Trudeau cabinet members.

Worse, the business press readily reported alarming forecasts that western Canada would lose untold billions in future wealth should the two new pipelines not get built. Those forecasts of forfeited wealth came from major Canadian banks which assumed, without providing evidence, that exported bitumen could fetch much higher prices from Asian refiners than U.S. counterparts now pay. The banks did not disclose that they also have billions in outstanding loans to oilsands and pipeline projects. I saw no media reports or commentators that called out this brazen conflict of interest.

In an equally glaring case, former Bank of Canada chief Mark Carney (who now heads the Bank of England and is a perennial newsmaker), warned on behalf of a consortium of central banks that global corporations involved in fossil fuel financing or production must assess and explicitly warn their shareholders about ‘stranded asset’ risks in a climate-constrained world. It fell on deaf ears at business news desks in Canada.

But last week, Europe’s largest bank, HSBC, joined other global banks, insurance pools and pension funds in declaring it would no longer risk loans to new oilsands projects, or planned pipelines like the Trans Mountain expansion and Keystone XL. That may amount to a final, fatal bullet aimed squarely at Alberta’s bitumen bubble.

For failures to unravel Looney Tunes logic, candidates abound. Alberta premier Rachel Notley, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and federal environment minister Catherine McKenna blithely claimed that ramping up carbon-laced bitumen exports would garner new cash to help pay for low-carbon investments in Alberta and B.C. marine safety upgrades. And that Canada could meet its solemn Paris pledge to reduce national carbon emissions while two oilsands provinces go totally rogue. Alberta touted its vaunted carbon tax on large emitters as a sign of climate leadership, but all future raw bitumen exports are exempt. Justin Trudeau’s Liberals promised a reform of national environmental assessment laws, then exempted oilsands and pipelines in the draft regulations.

Now, they are avowedly preparing to battle B.C. premier John Horgan over the Trans Mountain pipeline with whatever legal, fiscal or other weapons are required. There have been dark hints that federal troops might eventually be deployed along the pipeline route to maintain the ‘rule of law’. A titanic test of wills may be only weeks away. The first casualty of such a war, as always, will be the truth.

But what if this red-hot rhetoric, and a potentially ruinous breakdown in the bonds of Confederation, are actually warning signs that a bitumen bubble is beginning to crack open? Last year, Big Oil players dumped $22.5 billion in oilsands assets. If that is accurate, it is perhaps too much to expect politicians from Alberta and Ottawa to question the future their reputations and political fortunes rest on.

But when the stakes are so high, and when there are whiffs of panic, extortion and even all-out political warfare in the air, it is precisely the time business journalists should be asking tough questions and demanding answers. Where are the Asian contracts to buy vastly more raw bitumen for decades? What price have they promised to pay? How does that square up with competing, global oil supply rivals? Who has prepared a serious global oil market analysis?

That is our job. It is our professional, perhaps even patriotic, duty to do it well.

Paul McKay has won Canada’s top journalism awards multiple times for business, investigative and feature writing, and authored an acclaimed business biography. He is a past recipient of the Toronto Star/Atkinson Fellowship in Public Policy, and a past Pierre Berton Writer-in-Residence. His most recent e-book is The Art of the Expose: Dispatches from a Rebel Reporter.